kottke.org posts about LGBTQ

This piece by Lydia Polgreen on The Strange Report Fueling the War on Trans Kids is so good — straightforward and informative, especially when compared to the incoherent nonsense that the NY Times has run about trans people over the past few years. The piece is about, in Polgreen’s words, “the sneaky effort to use what looks like science to justify broad intrusions in our personal freedom”.

I usually don’t do this, but I’ve excerpted the article’s conclusion here because it just gets right to the heart of an urgent concern: the freedom to control our own bodies.

Imagine that your health care required objective justification, if access to birth control or erectile dysfunction medications required proving that you were having monogamous sex, or good sex, or sex at all. Or if fertility care was provided only if you could prove that becoming a parent would make you happy, or you would be a good parent. Or that abortion would be available only if you could prove that it would improve your life.

In a free society we agree that these are private matters, decided by individuals and their families, with the support of doctors using mainstream medical science as a guide, even when they involve children. We invite politicians and judges into them at great peril to our freedom.

I encourage you to read the whole thing — it’s interesting throughout.

Queendom is a documentary film by Agniia Galdanova about queer Russian activist and performance artist Jenna Marvin and her unusual form of protest against the war in Ukraine and Russia’s treatment of LGBTQ+ people. From a short review in the Guardian:

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February last year, some brave souls took to the streets of Moscow to voice their horror at the war, and were met with batons and police brutality. Radical queer performance artist Gena Marvin took a different approach. Wearing platform boots, body paint and wrapped in barbed wire, she walked the streets of Moscow in a stark, silent statement against the war. To call Gena a drag artist fails to capture just how subversive and courageous are her public “performances”. Her otherworldly costumes, created from junk and tape, show the influence of Leigh Bowery; her fearlessness evokes the punk provocation of Pussy Riot.

Marvin’s performances can be intense — check out this video from Paris in 2022. France had just advanced into the semifinals of the World Cup and she went out on the streets dressed in an all-black costume straight out of Alien or Pan’s Labyrinth:

Queendom opens in theaters and will available on streaming on June 14.

For the role of a teacher/coach in her new film Bottoms (about a pair of queer girls who start a fight club in their high school in order to get laid), director Emma Seligman made the unorthodox decision to cast former NFL player Marshawn Lynch. It turned out to be an inspired choice — according to an interview with Seligman, he was a natural.

He was one of the best improvisers I’ve ever worked with. I’m not overstating that. He improvised most of his stuff in the movie that ended up in the final cut! We couldn’t ever write something that would be as funny as what he gave us. He’d spew out the most brilliant jokes ever. I kept on encouraging him to do more improv. He’d be like, “Ugh, that stuff’s easy! I wanna get your words right!” I told him that it was so much better than anything we could have written and he was like, “I don’t care about this. I want to honor your work.” I’m so glad I got to talk about him this much.

Here’s a short clip of Lynch doing his thing as Mr. G, “an air-headed high school teacher”:

Lynch also used the film as an opportunity to make some amends for how he reacted when his sister came out as queer:

This was a good opportunity for me because when I was in high school, my sister had came out as being a lesbian or gay — I did not handle it right. You feel me, as a 16-year-old boy, I didn’t handle it the way that I feel like I probably should have. So I told [Seligman] it was giving me an opportunity to correct my wrongs, to rewrite one of my mistakes.

From that interview with Seligman again:

In our first conversation, he told me that his sister is queer and when they were in high school, he didn’t necessarily handle it super well. He felt like this movie coming into his hands was the universe giving him a chance to right his wrongs. That’s what he said. He walked her down the aisle. He felt like they were all good, you know? But his sister thought it’d be really cool if he did this.

If you have never seen this old interview with Lynch about the value of persistence, buckle up because you’re in for a treat:

In a June piece for The Guardian and the video above from just a few days ago, Robert Reich outlines five crises — including wokeness, the trans panic, and critical race theory — that Republicans have manufactured in order to deflect from their true agenda.

Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin’s “day one” executive order banned the teaching of critical race theory. DeSantis and Greg Abbott, the Texas governor, have also banned it from schools.

Here again, though, there’s no evidence of a public threat. CRT simply teaches America’s history of racism, which students need to understand to be informed citizens.

Banning it is a scare tactic to appeal to a largely white, culturally conservative voter base.

However, I would argue that Reich needed to go a bit further. While the crises are inventions, their consequences go beyond mere distraction and into the territory of active harm, particularly of queer and trans people, Black people, and people of color. That’s why I modified the title from his original.

From the Library of Congress, footage of the first gay pride march in NYC in 1970. The march, called the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade, was held on June 28 to commemorate the first anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. From Gothamist:

The Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day March started in Greenwich Village at about 2 p.m. that day in 1970, just outside the Stonewall Inn, which was then for rent, having closed the previous October.

As they gathered, the marchers were few, and brave. There were groups from Washington, DC and Boston, college organizations from Rutgers, Yale and Columbia. Some transgender people who were there at the time said that organizers asked them to march in the back, but they refused.

“The trans community said, ‘Hell no, we won’t go.’ We fought for this as much as you did, or even started it,” said Victoria Cruz. “And we just mingled throughout the crowd. There was no trans contingent. We just mingled.”

They started walking very briskly up Christopher Street, because they were scared. There had been bomb threats. People worried they would be shot at, or harassed again by the police. Martin Boyce was there, and he says that afterwards they joked it was “the first run.”

“I was worried about being single file, because I just watched a program on National Geographic about wildebeests and I saw how the ones on the side were picked off. So I thought I would stay in the middle — but there was no middle.”

As the march went on, it gathered people & momentum and they eventually made it without major incident to Central Park.

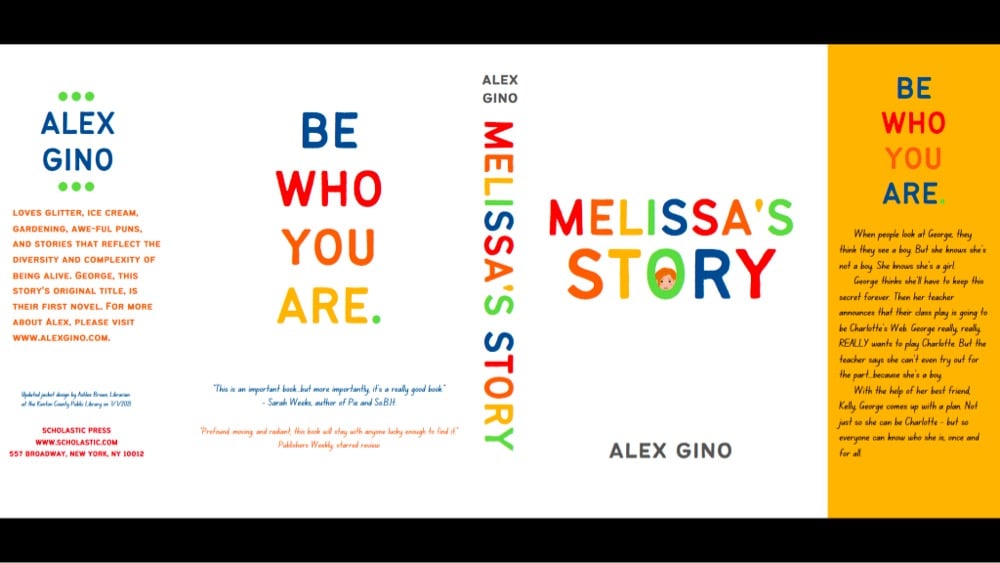

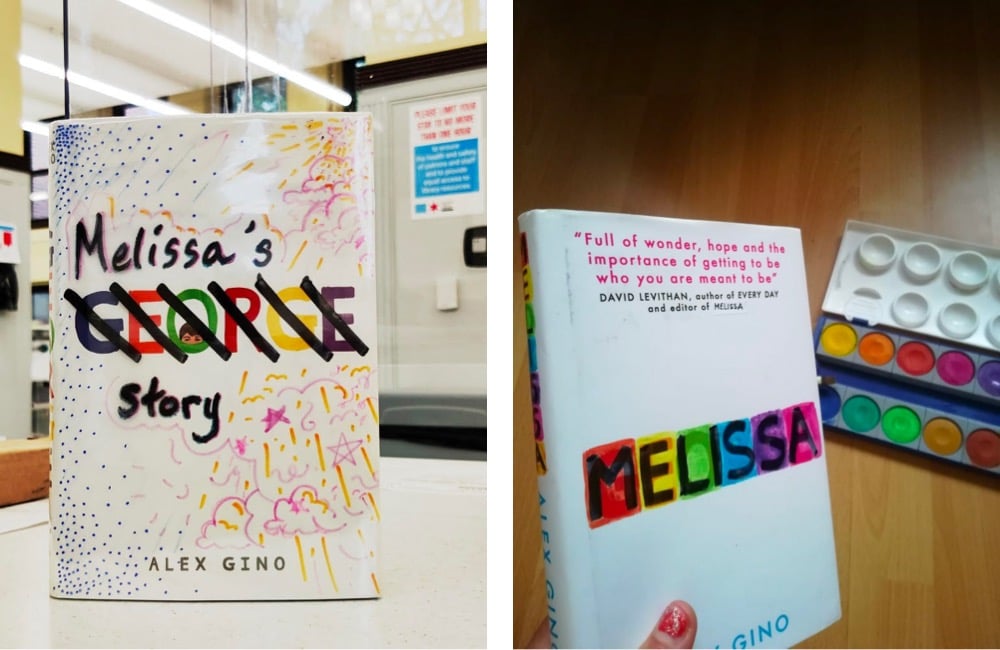

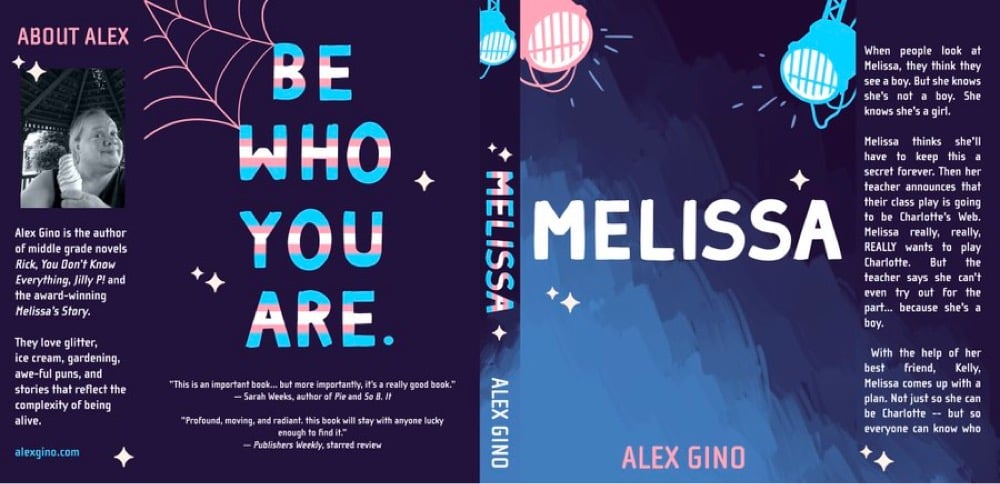

In 2015, Alex Gino published George, a children’s novel about a trans girl named Melissa — George was the character’s former name. Since its publication, many of the book’s fans have grown to dislike the title, saying that it elevated the deadname of the character instead of her actual name. Earlier this year, Gino and their publishing company announced that the title of the book is officially changing to Melissa.

No matter how many people have come to know it as George, we felt it was important to fix the title. What we call people matters and we all deserve to be referred to in ways that feel good to us. Calling the book Melissa is a way to respect her, as well as all transgender people. The text inside won’t change, so the name George will still appear to reflect the character’s growth within the novel, but Melissa will be the first name readers will know her by.

But even before that, readers began making their own modifications to the cover with Sharpies, crayons, colored pencils, and even entire dust jackets. On their blog, Gino explained why the book was called George in the first place and shared some of the amazing art that fans made to correct the title.

Melissa will be out in April and is available for preorder now. (thx, caroline)

In a two-part video series called Trans Dudes From History, Jackson Bird tells us about some historical people who were probably transgender or transmasculine.

Trans people have always existed, even if they didn’t have the same language we do now and even if most history books won’t tell you about them. In this first volume of my Trans Dudes From History series, I give an introduction to talking about people from history who maybe could’ve been trans and share the profiles of three people — a Spanish conquistador, a stagecoach driver, and a bronco buster — who all transgressed gender in some way.

The introduction in the first video (embedded above) — about history and how we even know people were trans before the language around that was even invented — is really interesting. Part two of Trans Dudes From History is right here.

In a TEDx Talk from 2017, LB Hannahs talks about their experience as a transgender dad, comfort vs authenticity, and the collision of theoretical gender roles & identities with the practicalities of parenthood.

Now, for most people, what their child will call them is not something that they give much thought to outside of culturally specific words or variations on a gendered theme like “mama,” “mommy,” or “daddy,” “papa.” But for me, the possibility is what this child, who will grow to be a teenager and then a real-life adult, will call me for the rest of our lives, was both extremely scary and exciting. And I spent nine months wrestling with the reality that being called “mama” or something like it didn’t feel like me at all. And no matter how many times or versions of “mom” I tried, it always felt forced and deeply uncomfortable. I knew being called “mom” or “mommy” would be easier to digest for most people. The idea of having two moms is not super novel, especially where we live.

So I tried other words. And when I played around with “daddy,” it felt better. Better, but not perfect. It felt like a pair of shoes that you really liked but you needed to wear and break in. And I knew the idea of being a female-born person being called “daddy” was going to be a harder road with a lot more uncomfortable moments. But, before I knew it, the time had come and Elliot came screaming into the world, like most babies do, and my new identity as a parent began. I decided on becoming a daddy, and our new family faced the world.

(thx, megan)

Over at A Cup of Jo, Joanna Goddard interviewed three kids who are transgender about their experiences. Here’s Violet, she/her, age 13:

What do you wish people knew about being trans?

The main thing is that it’s not a choice. It’s a choice to come out, but being trans is not a choice. It wasn’t like one day I woke up and felt the way the wind blew and wanted to be a girl. I ALWAYS knew I wasn’t a boy. It wasn’t that I wanted to be a girl; I WAS a girl. I just had to put that into words and explain that.

Aya, she/her, age 9:

How did you tell your parents?

There was one night when my sister was like, ‘So… Mommy’s a girl, I’m a girl, Daddy’s a boy, and you’re a boy.’ But I immediately was like, ‘No, no, I’m a girl.’ And that was the first time, but there was another time. We were driving back from Mommy’s school, and she was telling me about the different words like transgender and all different words and when she described transgender, I was like, that’s me. I was five.

And this:

Also, fun fact: When we were watching a Mo Willems episode about drawing, he told us that his child is transgender — the one from Knuffle Bunny. Trixie is now Trix!

The comments on the post are worth reading as well — CoJ has the best comments section on the internet, quite a feat for 2021.

In this short film from Alex Mallis, we meet a Bronx couple who are raising their child Grey in a gender-neutral way until they make a decision for themselves. No single gender wardrobes or toy collections and they/them pronouns.

Really the goal here is, it’s not about me trying to force anything on Grey, it’s actually the exact opposite. And we don’t know their gender yet, and when they tell us, they’ll tell us. And it might change over time and that’s okay too.

Crispin Long wrote an accompanying piece for the New Yorker on the film.

Watching Grey’s parents navigate this terrain inspires questions about how Grey might one day respond to being brought up this way. Of course, it’s impossible to parent without error, and society does its share of damage, to many of us, without the help of parents. Asking a child to inhabit such a complex and politicized position is demanding, but so is asking a child to perform femininity or masculinity. I get the sense that many trans people would unambivalently prefer to have been raised without the gender they were assigned at birth and its attendant expectations. For me, it’s less clear. If my parents had made every effort to free me from the strictures of the gender binary, I might have rebelled against their liberal piety or appreciated their efforts — or maybe both.

Jackson Bird, who kottke.org readers may know as the host of Kottke Ride Home, recently made a video showing his lifelong transition from the assignment he was given at birth to “the man I am today”.

Instead of photos, I used thirty years worth of home videos to share my story. I called this my Five Years On Testosterone video, but it could more accurately be called Thirty Years In Transition. This is three decades worth of what it looks like to be a transgender person. From childhood tomboy days to confusion and questioning to denial and finally coming out, starting hormones, changing my name, getting top surgery, and all of the moments in between. Not all of our stories are the same, far from it, but this is one story — my story. The story of how I became the man I am today.

What a great video and fantastic storytelling. Undertaking a journey in public like this cannot be easy; thanks for sharing this with us, Jackson. If you’d like to know more about his story, check out his memoir: Sorted: Growing Up, Coming Out, and Finding My Place.

Meet Kodo Nishimura, a Buddhist monk and makeup artist. Nishimura, who is gender fluid and uses he/him pronouns, struggled with his peers’ rigid concepts about gender as a teen in Japan, but found greater acceptance and a career in NYC before deciding to return to Japan to train as a monk, just as his parents had before him. As you might imagine for someone with one foot in two very different cultures, it has been difficult for Nishimura to simultaneously navigate both of those worlds and their attendant expectations.

For the next two years, Nishimura lived a double life: an openly gay makeup artist when he was in NYC and a closeted Buddhist monk trainee when he was in Japan. “I didn’t want the impression of other monks to be degraded because of me,” he recalls. It wasn’t until confiding in his master that Nishimura realized the futility of his concerns. His master expressed: “The most important message of our denomination [Pure Land Buddhism] is to let people know that we can all be saved regardless of our sexuality, gender or fashion preferences.”

You can check out more about Nishimura on his website or on Instagram. (via spoon & tamago)

Update: Thanks to Caroline and @anatsuno for some language-related feedback on this post. I added that Nishimura explicitly uses he/him pronouns and clarified that he “is gender fluid” and not just “identifies as gender fluid”.

Like many people my age, Mister Rogers had a large influence on me in terms of how to act as a man. As Maxwell King wrote in The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers, he was not perceived at the time to be traditionally masculine:

Rogers himself was often labeled “a sissy,” or gay, in a derogatory sense. But as his longtime associate Eliot Daley put it: “Fred is one of the strongest people I have ever met in my life. So if they are saying he’s gay because… that’s a surrogate for saying he’s weak, that’s not right, because he’s incredibly strong.” He adds: “He wasn’t a very masculine person, he wasn’t a very feminine person; he was androgynous.”

In a 1975 interview for the New York Times, Rogers noted drolly: “I’m not John Wayne, so consequently, for some people I’m not the model for the man in the house.”

When I was little, Mister Rogers was the man of the house. My dad worked a lot and I sometimes only saw him for a few hours on weekends. Instead, my male role models were Captain Kangaroo, the men of Sesame Street (Mr. Hooper, Bob, Gordon, and Luis), and, most of all, Fred Rogers.

Now, some in the LGBTQ+ community are finding Fred Rogers to be a posthumous bisexual role model. Directly after the passage above, King continues:

In conversation with one of his friends, the openly gay Dr. William Hirsch, Fred Rogers himself concluded that if sexuality was measured on a scale of one to ten: “Well, you know, I must be right smack in the middle. Because I have found women attractive, and I have found men attractive.”

As Out’s Mikelle Street notes, it’s tough to tell what Rogers meant by that in terms of his sexuality. We do know he was married to his wife Joanne for more than 50 years until his death in 2003. Rogers also advised François Clemmons, who played Officer Clemmons and came out as gay during his time on the program (though not on air), to not go to gay bars while working on the show and encouraged him to marry a woman.

Clemmons did but then divorced his wife to live as an openly gay man, piercing his ear as a sign of his sexuality. He was not allowed to wear earrings while filming though — for years Clemmons masked his own sexuality, under the advice of Rogers, in an effort to be successful.

Could it be that the actor was less forthcoming about his sexuality because he understood what Hollywood then required for success?

If Street is right, perhaps Rogers didn’t come out publicly about his sexuality for the same reason he advised Clemmons to mask being gay and the same reason millions of other people didn’t in the 70s and 80s: fear of social stigma. As King repeatedly writes in the book, Rogers always put the needs of the small children who watched his program above all other concerns. Perhaps he felt that a potential scandal about his sexuality, even a small one, was not worth jeopardizing his relationship with his television neighbors.

For Clemmons though, there was little doubt that Rogers accepted him for who he was:

He says he’ll never forget the day Rogers wrapped up the program, as he always did, by hanging up his sweater and saying, “You make every day a special day just by being you, and I like you just the way you are.” This time in particular, Rogers had been looking right at Clemmons, and after they wrapped, he walked over.

Clemmons asked him, “Fred, were you talking to me?”

“Yes, I have been talking to you for years,” Rogers said, as Clemmons recalls. “But you heard me today.”

“It was like telling me I’m OK as a human being,” Clemmons says. “That was one of the most meaningful experiences I’d ever had.”

Update: Clemmons spoke at length in this Vanity Fair interview about his relationship with Rogers, his sexuality, and appearing on the show. One excerpt:

And [during the show], I could not handle people having an open discussion about the fact that François Clemmons is living with his lover. I did feel like I was risking [something], because people knew who I was. I had a full conversation with Fred about what it could possibly do to the program and to my role on the program, and I didn’t feel I wanted to risk it. You know, the articles that have talked about me, I don’t think they’ve taken into full account that societal norms were vastly different than what they are right now.

Verena is an iOS app designed to protect and help guide you through situations like “domestic violence, hate crimes, abuse, and bullying”. The app was developed with the LGBTQ+ community in mind, but can be used by anyone facing abuse or harassment.

Create an account, and develop a network of emergency contacts, who can be alerted without leaving a trace on your phone.

Use the emergency feature to be guided through your problem, giving you the resources you need to get out of the emergency safely.

Create incident logs to keep track of abuse, hate crimes, or bullying for reference and later reportation.

Select the preferences that match your situation, such as using incognito mode to hide the app behind a math user interface, shutdown which can permanently disable the app if found by an abuser, and emergency access which allows you to alert all of your contacts with the press of a button.

Open resources to find and get routed to hospitals, shelters, and police stations near you.

Use timer to set a specified amount of time. If the timer isn’t canceled, Verena will send an emergency alert to all contacts with your last known location.

Select location to see your current location, the distance between you and your different contacts, and get routed to them as well.

Verena was built by Amanda Southworth, a 16-year-old iOS developer who created the app to help her LGBTQ+ friends in the aftermath of the election of a known abuser to the White House in 2016:

Seeing her friends — many of whom are part of the LGBT community — worry the day after the presidential election in November 2016 inspired her to create the app. “That day I saw all of my friends crying and it was really upsetting, you know, when people you love are scared,” she says. “So I decided, I’m going to make something so that I know they’re safe.”

Verena, which takes its name from a German name that means “protector,” allows users to find police stations, hospitals, shelters, and other places of refuge in times of need. They can also designate a list of contacts to be alerted via the app in an emergency.

Southworth, whose first iOS app was a “mental health toolkit” called anxietyhelper, attended Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference this past summer and wrote about it for Teen Vogue. She also gave a TEDx talk about “how her struggle with mental illness and suicidal thoughts inspired her start coding”.

In this short animated film, a boy’s heart brings him closer to the boy he has a crush on. What a lovely little video. It was made by Ringling College of Art and Design students Beth David and Esteban Bravo as their computer animation thesis and funded via Kickstarter.

Check It is a documentary film about a Washington DC gang with an all-LGBT+ membership.

At first glance, they seem unlikely gang-bangers. Some of the boys wear lipstick and mascara, some stilettos. They carry Louis Vuitton bags, but they also carry knives, brass knuckles and mace. As vulnerable gay and transgender youth, they’ve been shot, stabbed, and raped.

Once victims, they’ve now turned the tables, beating people into comas and stabbing enemies with ice picks. Started in 2009 by a group of bullied 9th graders, today these 14-22 year old gang members all have rap sheets riddled with assault, armed robbery and drug dealing charges.

Led by an ex-convict named Mo, Check It members are now creating their own clothing label, putting on fashion shows and working stints as runway models. But breaking the cycle of poverty and violence they’ve grown up in is a daunting task.

Louis CK is one of the films executive producers and he has put the film up on his site as a $5 download. In a recent newsletter, he explained why:

Look, I know this isn’t what you’re expecting from me. Nor am I the guy you’re expecting to get this film from. I guess that’s why I’m doing this. When I saw this film, I knew that no one I know will ever see it. Documentaries are MUCH harder to make than the things that I do and they are FAR more expensive to the filmmakers in terms of their time and their lives and their emotional energy. And nobody much watches them. Those who do watch documentaries are usually people who are likely to be interested in the subject they cover already. But what a great value there is in showing people films about something that just isn’t on their radar. So that’s why I asked Steve, and Wren Arthur, who produced the film, if I could host “Check It” on my site so that lots of people can see it who may not have had it put in front of them.

Over a number of recent summers, well-known portrait photographer Mark Seliger has been documenting the transgender community that gathers on Christopher St in the West Village. Since Seliger’s website is slow and bloated, I’d recommend checking out coverage of the photos on The Advocate, The New Yorker, American Photo, and PDN. I lived on Christopher Street for several years1 and definitely recognize a couple of people in Seliger’s photos.

It was in the Village, on Christopher Street and the nearby piers, where many trans and queer people first shared space with others like them. For generations, these places provided mirrors for those who rarely saw reflections of themselves. On Christopher Street, there were multitudes of potential selves: transgender, transsexual, non-binary, genderqueer, femme, butch, cross-dresser, drag king or queen, and other gender identities and sexual orientations that challenge social norms.

Seliger has collected the photos into a book, On Christopher Street: Transgender Stories and the photos will be on display at 231 Projects in Chelsea until early January.

My friend Matt Thompson grew up in Orlando, and like many of the shooters’ victims, he’s gay, a person of color, and a child of immigrants to the US. His wonderful essay grapples with the shooting and tries to untie the fear and risk and hope and community that’s knotted up in those identities.

My own parents were the very last people in my life I was out to, years after I’d been out to friends and colleagues. I didn’t know how they’d react to the fact of my sexuality, and among my friends, there was often impatience with that uncertainty. If they’re good parents, these friends would say, they will love you without conditions and without hesitation.

But this reaction was rare among those of us who grew up, like me, knowing that our parents left their homes and settled here mainly in pursuit of visions of what their children’s lives would be. They had imagined their sons as men with wives, and their daughters as women with husbands, and cultivated these visions throughout our adolescence and beyond. Some of our parents had tended to these visions so zealously that they missed all the signs that these weren’t, in fact, the people we’d become. When we came out, they were forced both to reckon with these people they no longer recognized and mourn the visions of us they had nurtured all those years.

“I can’t stop thinking about the possibility that someone like us was hurt or murdered at Pulse on Sunday morning,” Matt writes. “outed in the very worst way, in a phone call every family dreads. For some parents, such a call would be a double heartbreak.”

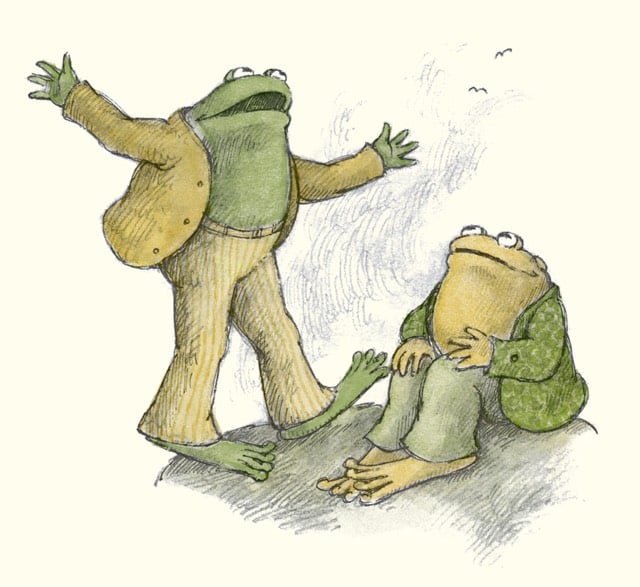

Bert Clere wrote a nice appreciation for the children’s books of Arnold Lobel, among them the Frog and Toad series and Owl at Home. Clere says Lobel’s stories offered insights for children about, yes, friendship but also about the importance of individuality.

Lobel’s Frog and Toad series, published in four volumes containing five stories each during the 1970s, remains his most popular and enduring work. Frog and Toad, two very different characters, make something of an odd couple. Their friendship demonstrates the many ups and downs of human attachment, touching on deep truths about life, philosophy, and human nature in the process. But it isn’t all about relationships with others: In the series, and in his lesser-known 1975 book Owl at Home, Lobel offers a conception of the self that still resonates decades later. Throughout his books, he reminds readers that they are individuals, and that they shouldn’t be afraid of being themselves.

Frog and Toad are favorites at our house. I’m going to read them to the kids this weekend with a new appreciation. Wanting to fit into the group is a powerful impulse for children, reinforced these days by the increased focus on group work in schools, so it’s nice to have a counterpoint to share with them.

Update: From the New Yorker’s Colin Stokes, another appreciation of Arnold Lobel. Lobel’s daughter Adrianne suspects the Frog & Toad books were “the beginning of him coming out” of the closet.

Adrianne suspects that there’s another dimension to the series’s sustained popularity. Frog and Toad are “of the same sex, and they love each other,” she told me. “It was quite ahead of its time in that respect.” In 1974, four years after the first book in the series was published, Lobel came out to his family as gay. “I think ‘Frog and Toad’ really was the beginning of him coming out,” Adrianne told me.

The article also sadly notes that Lobel died at age 54, “an early victim of the AIDS crisis”. (via @bdeskin)

Charles Haggerty is a promising candidate for the best and most chill dad of all time. In the late 1950s, in a much less progressive era, he had a talk with his son, who would come to realize later in life that he (the son) was gay, about the responsibility you have to your true self.

Don’t sneak. Because if you sneak like you did today, it means you think you doing the wrong thing. And if you run around spending your whole life thinking that you’re doing the wrong thing, then you’ll ruin your immortal soul.

Reader, I don’t often say things like “that stopped me dead in my tracks” because life doesn’t work like that most of the time, but that last bit, about ruining your soul, did just that. A fantastic reminder of to thine own self be true. (via cup of jo)

The Danish Girl is an upcoming film starring Eddie Redmayne as transgender pioneer Lili Elbe, who was one of the first people to undergo gender reassignment surgery. It’s based on a novel of the same name which presents a fictionalized account of Elbe’s life.

The film may well net Redmayne another Oscar nomination, but I don’t know how the transgender community will react. From a quick look on Twitter and the past reception of Oscar-hopeful films dealing with similar issues (see The Imitation Game’s portrayal of Alan Turing’s sexuality), I’m guessing it may not be so well-received.

Polari was a secret slang language spoken by gay men in England so that they could converse together in public without fear of arrest. It fell into disuse in the 1960s, but this short film by Brian Fairbairn and Karl Eccleston features a conversation conducted entirely in Polari.

This Slate article has more on the film and Polari.

Of all the cultural forms that gay men have created and elaborated since coalescing into a social group around the late 19th century, Polari, a full-fledged gay English dialect with roots among circus folk, sailors, and prostitutes, has to be one of the most fascinating-not least since it has faded along with the need for discretion and secrecy. While some words remain in common use-zhush or zhoosh (to adjust or embellish something to make it more pleasing) and trade (highly masculine or straight-acting sex partners) come to mind — the richness that we know once defined Polari is difficult to capture in 2015.

Added to the series of things I thought I posted about but never did is Steve Silberman’s new book, NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity, out next week.

What is autism? A lifelong disability, or a naturally occurring form of cognitive difference akin to certain forms of genius? In truth, it is all of these things and more-and the future of our society depends on our understanding it. WIRED reporter Steve Silberman unearths the secret history of autism, long suppressed by the same clinicians who became famous for discovering it, and finds surprising answers to the crucial question of why the number of diagnoses has soared in recent years.

Jennifer Senior wrote a largely positive review for the NY Times.

“NeuroTribes” is beautifully told, humanizing, important. It has earned its enthusiastic foreword from Oliver Sacks; it has found its place on the shelf next to “Far From the Tree,” Andrew Solomon’s landmark appreciation of neurological differences. At its heart is a plea for the world to make accommodations for those with autism, not the other way around, and for researchers and the public alike to focus on getting them the services they need. They are, to use Temple Grandin’s words, “different, not less.” Better yet, indispensable: inseparably tied to innovation, showing us there are other ways to think and work and live.

Update: NeuroTribes has won the prestigious 2015 Samuel Johnson prize for non-fiction. The Guardian’s Stephen Moss interviewed Silberman about the prize and book.

Silberman was born in New York, the son of two teachers who were communists and anti-war activists. “I was raised to be sensitive to the plight of the oppressed. One of the things I do is frame autism not purely in a clinical or self-help context, but in a social justice context. I came to it thinking I was going to study a disorder. But what I ended up finding was a civil-rights movement being born.”

He says the fact he is gay also conditioned his approach. “My very being was defined as a form of mental illness in the diagnostic manual of disorders until 1974. I am not equating homosexuality and autism — autism is inherently disabling in ways that homosexuality is not — but I think that’s why I was sensitive to the feelings of a group of people who were systematically bullied, tortured and thrown into asylums.”

Tyler Ford was born a girl, transitioned to being a man in college, but now identifies as an agender person.

I have been out as an agender, or genderless, person for about a year now. To me, this simply means having the freedom to exist as a person without being confined by the limits of the western gender binary. I wear what I want to wear, and do what I want to do, because it is absurd to limit myself to certain activities, behaviours or expressions based on gender. People don’t know what to make of me when they see me, because they feel my features contradict one another. They see no room for the curve of my hips to coexist with my facial hair; they desperately want me to be someone they can easily categorise. My existence causes people to question everything they have been taught about gender, which in turn inspires them to question what they know about themselves, and that scares them. Strangers are often desperate to figure out what genitalia I have, in the hope that my body holds the key to some great secret and unavoidable truth about myself and my gender. It doesn’t. My words hold my truth. My body is simply the vehicle that gives me the opportunity to express myself.

Ford uses the “they”, “them”, and “their” pronouns to refer to themselves. (Is it themselves? Or would it be themself? English is a relatively young and fluid language but even it can’t keep up.)

MoMA has announced that they’ve acquired the Rainbow Flag for their permanent collection. The flag has been a symbol of the LGBT community around the world since its creation in 1978. As part of the acquisition, MoMA Curatorial Assistant Michelle Millar Fisher interviewed the man who designed the flag, artist Gilbert Baker.

And I thought, a flag is different than any other form of art. It’s not a painting, it’s not just cloth, it is not a just logo — it functions in so many different ways. I thought that we needed that kind of symbol, that we needed as a people something that everyone instantly understands. [The Rainbow Flag] doesn’t say the word “Gay,” and it doesn’t say “the United States” on the American flag but everyone knows visually what they mean. And that influence really came to me when I decided that we should have a flag, that a flag fit us as a symbol, that we are a people, a tribe if you will. And flags are about proclaiming power, so it’s very appropriate.

So the American flag was my introduction into that great big world of vexilography. But I didn’t really know that much about it. I was a big drag queen in 1970s San Francisco. I knew how to sew. I was in the right place at the right time to make the thing that we needed. It was necessary to have the Rainbow Flag because up until that we had the pink triangle from the Nazis — it was the symbol that they would use [to denote gay people]. It came from such a horrible place of murder and holocaust and Hitler. We needed something beautiful, something from us. The rainbow is so perfect because it really fits our diversity in terms of race, gender, ages, all of those things. Plus, it’s a natural flag — it’s from the sky! And even though the rainbow has been used in other ways in vexilography, this use has now far eclipsed any other use that it had…

Update: Baker died at his home on March 30, 2017. He was 65 years old.

Mr. Baker replicated his flag dozens of times over the years. He crafted a mile-long banner to parade down Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, and he sent flags around the world in support of gay rights protests. He sewed the rainbow flag used in the movie “Milk,” along with a new flag for this year’s television miniseries “When We Rise.”

“I remember the most fabulous queen I’d ever seen in my life shows up in sequins with a sewing machine in his arms, and he insisted on creating that flag exactly the same way he’d created it then,” said Dustin Lance Black, who wrote “Milk” and wrote and directed “When We Rise,” which was based on Jones’ memoir of the same name.

After the end of World War II in Europe, homosexual prisoners of liberated concentration camps were refused reparations and some were even thrown into jail without credit for their time served in the camps. From the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

After the war, homosexual concentration camp prisoners were not acknowledged as victims of Nazi persecution, and reparations were refused. Under the Allied Military Government of Germany, some homosexuals were forced to serve out their terms of imprisonment, regardless of the time spent in concentration camps. The 1935 version of Paragraph 175 remained in effect in the Federal Republic (West Germany) until 1969, so that well after liberation, homosexuals continued to fear arrest and incarceration.

After 1945, it was no longer a crime to be Jewish in Germany, but homosexuality was another matter. Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code had been on the books since 1871. An English translation of the earliest version read simply:

Unnatural fornication, whether between persons of the male sex or of humans with beasts, is to be punished by imprisonment; a sentence of loss of civil rights may also be passed.

In Germany, homosexuality was considered a crime worthy of up to five years of imprisonment until Paragraph 175 was voided in 1994.

Update: I missed this while writing the post: Paragraph 175 was amended in 1969 to limit enforcement to engaging in homosexual acts with minors (under 21 years). (thx, eric)

In an article for Businessweek, Apple CEO Tim Cook publicly reveals he is gay.

At the same time, I believe deeply in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, who said: “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’ ” I often challenge myself with that question, and I’ve come to realize that my desire for personal privacy has been holding me back from doing something more important. That’s what has led me to today.

For years, I’ve been open with many people about my sexual orientation. Plenty of colleagues at Apple know I’m gay, and it doesn’t seem to make a difference in the way they treat me. Of course, I’ve had the good fortune to work at a company that loves creativity and innovation and knows it can only flourish when you embrace people’s differences. Not everyone is so lucky.

While I have never denied my sexuality, I haven’t publicly acknowledged it either, until now. So let me be clear: I’m proud to be gay, and I consider being gay among the greatest gifts God has given me.

For the latest installment of Grantland’s 30 for 30 short documentary series, a story on the genesis of the high five and what happened to one of its inventors. This video is chock full of amazing vintage footage of awkward high fives. [Weird aside: The sound on this video is only coming out of the left channel. Is that a subtle homage to the one-handed gesture or a sound mixing boner?]

GLAAD has a good resource on transgender identity: Transgender 101.

Gender identity is someone’s internal, personal sense of being a man or a woman (or as someone outside of that gender binary.) For transgender people, the sex they were assigned at birth and their own internal gender identity do not match.

Trying to change a person’s gender identity is no more successful than trying to change a person’s sexual orientation — it doesn’t work. So most transgender people seek to bring their bodies more into alignment with their gender identity.

People under the transgender umbrella may describe themselves using one (or more) of a wide variety of terms, including transgender, transsexual, and genderqueer. Always use the descriptive term preferred by the individual.

In writing here, I sometimes get tripped up on the differences between sex, gender, and sexual orientation. No more. See also Tips for Allies of Transgender People and An Ally’s Guide to Terminology: Talking About LGBT People & Equality.

Matt Duron is a self-proclaimed “guy’s guy” who has a son who is “gender creative” (love that phrase) and wants to be treated like a girl.

My wife also gets a load of emails from people asking where our son’s father is, as though I couldn’t possibly be around and still allow a male son to display female behavior. To those people I say, I’m right here fathering my son. I want to love him, not change him. My son skipping and twirling in a dress isn’t a sign that a strong male figure is missing from his life, to me it’s a sign that a strong male figure is fully vested in his life and committed to protecting him and allowing him to grow into the person who he was created to be.

I may be a “guy’s guy,” but that doesn’t mean that my son has to be.

More parents like this please.

Older posts

Stay Connected