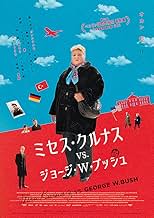

This movie defuses the sensationalisms typical of the great anti-system stories through irony; also it is devoid of the usual knee-jerk anti-americanism of too many euopean fils when they deal with questions in which american policies are less than fair and correct like the twin wars in Afghanistan and Irak. Between the start and the end of Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush are highlighted a couple of significant moments, both marked by the faces of two conservative heads of state, visible on the television screen. The first is that of Bush Jr., in the aftermath of the attack on the Twin Towers. The second is that of Angela Merkel, at the time of her election as Federal Chancellor of Germany. The camera seems to frame them in the same way, with the television image ideally replacing the cinematographic one. If the first, Bush jr, returns the figure of otherness, of the one who in the course of the story will be exalted as a symbol and spokesperson for the injustices of the American anti-terrorist system, the second, A. Merkel, takes on an opposite, almost salvific value. Not only for the speed with which the newly elected government corrects the political mistakes of the previous German administration, but for what the wind of change brings for the film's desperate protagonist. She resigned at that moment to the possibility that her son would never return from the Cuban prison of Guantánamo. Inspired by true events, Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush recounts the legal (and emotional) odyssey that the Turkish housewife Rabiye Kurnaz (Meltem Kaptan) had to face from 2001 to 2006 to ascertain the innocence of her son, and ensure his return to Germany from the terrible detention. Like many of the Guantánamo detainees of that period, the young Murat had no ties to Al Qaeda or affiliations of any kind to terrorist organizations. His only fault was that he was in Karachi, Pakistan, where some of the terrorists responsible for the attack were staying. An already dramatic situation, which Andreas Dresen however chooses to tell through the canons of comedy. In order to retrace the (extra) ordinariness of the matter, through the most eminently ridiculous emotions and drifts of everyday life. In this sense, the efforts, doubts and frantic battles of Rabiye and her lawyer Bernhard Docke (Alexander Scheer) open up in the eyes of the public as glimpses of everyday life, with all the ensuing repercussions in terms of emotional communication. Seeing a mother's courage in transcending the impossible thus becomes for the spectator the preferential path to empathy, and for the film a way (even a little good-natured and condescending) of defusing the sensationalisms typical of great stories through irony of anti-systemic revenge. And like works like Philomena or Erin Brockovich this film manages to fluidly link the narrative trope of "David vs. Goliath" to the overwhelming charisma of its (however earthy) heroine. If anything, the problem lies in the lightness with which it glosses over the socio-political ramifications behind the battle. In the obsessive propensity to sweeten a more complex and articulated subject than that testified by the images of the story. Also (and above all) with regard to its most critical consequences. Here, only the detail of her is of interest: that is, giving life to the sincere and faithful portrait of a mother, grappling with radical situations that lead her to question the nature of her motherhood.