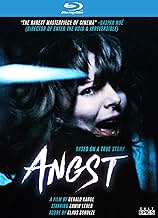

A troubled man gets released from prison and starts taking out his sadistic fantasies on an unsuspecting family living in a secluded house.A troubled man gets released from prison and starts taking out his sadistic fantasies on an unsuspecting family living in a secluded house.A troubled man gets released from prison and starts taking out his sadistic fantasies on an unsuspecting family living in a secluded house.

Robert Hunger-Bühler

- Off-Text

- (voice)

Silvia Ryder

- Daughter (Silvia)

- (as Silvia Rabenreither)

Karin Springer

- Daughter

- (voice)

Josefine Lakatha

- Mother

- (voice)

Helmut Hrdina

- Prison Guard

- (as Major Helmut Hrdina)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaPig's blood, not stage blood, was used for the stabbing scene, for the sake of additional realism.

- GoofsWhen the daughter picks up the knife with her mouth it suddenly has changed into an upright position.

- Quotes

[first lines]

The Psychopath: The fear in her eyes and the knife in the chest. That's my last memory of my mother. That's why I had to go to prison for four years, even though she survived.

- Alternate versionsTwo versions of the film exist, the 87-minute version originally released to theatres and a 79-minute version that would be considered the director's cut. The longer version includes a prologue that was added by director Gerald Kargl in response to theatrical distributors who felt the film was too short. It includes a brief murder scene of K's first victims and a narrator recalling details of the man's youth, details which are mostly redundant with some of the narrative reflection later in the film. The shorter version, known as Kargl's preferred version, eliminates those eight minutes entirely.

- ConnectionsEdited into Erwin Leder in Fear (2015)

Featured review

Word on the street is this is a super intense, gruelling, claustrophobic serial killer film. They're not lying. But it's important to get to note why, especially in this case: why this type of violence enthralls so much? And I mean apart from any particular on-screen nastiness. More virulent films have been made, much nastier. Why this fascinates is a completely different beast than say, something like Hostel.

It's the easiest thing to make us cringe and shy away, but to fervently want to keep watching?

The popular opinion is this works so well exactly because of how contained and straight-forward. There are no distractions from the concentrated moment we first encounter: a inmate giving himself a shave on his day of parole. There are no allusions to anything else but private madness and nothing to escape to for comfort or respite, except perhaps sheer exhaustion. This man is going to go on a crime spree again as soon as he's out of prison, we can tell this much. We can tell it's going to unravel the way we secretly hope it does.

Well, this is fine and makes some sense. But doesn't adequately explain to my mind. No, why this works so viscerally - and ties in with other interests of mine in film - I believe has all to do with the cinematic eye.

Now most films operate on the assumption that you want to experience a world as real as possible. Every advance in cinematic technology - sound, color, the recent fad of 3D - is a step in that direction. We want to escape more vividly and more urgently than ever. And what most films do to abet that escape is to let loose a few threads of story and place, hopefully open enough if we are in caring hands, that we can be trusted to attach ourselves from own experience. The tighter the weave of the threads from that point on, the closer we are lassoed to the cinematic world. Editing and camera are assigned invisible ways; they have to work without us getting to notice.

The Soviets changed all that very early in the game. Here a very world was assembled by the eye. There was no story, it was all a matter of calligraphic (dynamic overlapping) watching. Welles, and less famously Sternberg before him, unpacked these notions by letting it fall on the eye of the camera to join fragments together.

(this particular eye was first conceived by the Buddhist but that's another story altogether).

Now this is rumored to be the DP's project working under an alias, a Polish man who knows the camera. The opening shot exhibits masterful knowledge of Welles; a crane shot that establishes location by joining together many different planes of perspective. It would have been a film to watch with just this mode, that others like Argento and DePalma exercised in adventurous flourishes of spatial exploration.

It's actually a little more elaborate than that. We have two eyes instead of the one. The first is the killer's eye, tightly screwed and always at eye-level as he prowls around. Interior monologue plays out in voice-over, itself taken from the diaries of an actual killer, and meant to recast everything as internal space: victims are an invalid, an old woman and her daughter, each one mapping to a person that deeply wounded in the past as we find out. So we have exceedingly tormented soul spilled out and contorting physical space, very much like Zulawski practiced. Another Pole, another piece of the puzzle.

The second eye you will notice is always mounted on a crane and pulled upwards in steep ascends. A bird's eye far removed from human madness, which is the Buddhist eye of woodblock prints. To the film's credit, and this is a lot of its power for me, it remains abstract enough that we may use this perspective as we are inclined: is it a godless and uncaring or a merciful eye, pulling us from the carnage or skipping to the next?

It's the easiest thing to make us cringe and shy away, but to fervently want to keep watching?

The popular opinion is this works so well exactly because of how contained and straight-forward. There are no distractions from the concentrated moment we first encounter: a inmate giving himself a shave on his day of parole. There are no allusions to anything else but private madness and nothing to escape to for comfort or respite, except perhaps sheer exhaustion. This man is going to go on a crime spree again as soon as he's out of prison, we can tell this much. We can tell it's going to unravel the way we secretly hope it does.

Well, this is fine and makes some sense. But doesn't adequately explain to my mind. No, why this works so viscerally - and ties in with other interests of mine in film - I believe has all to do with the cinematic eye.

Now most films operate on the assumption that you want to experience a world as real as possible. Every advance in cinematic technology - sound, color, the recent fad of 3D - is a step in that direction. We want to escape more vividly and more urgently than ever. And what most films do to abet that escape is to let loose a few threads of story and place, hopefully open enough if we are in caring hands, that we can be trusted to attach ourselves from own experience. The tighter the weave of the threads from that point on, the closer we are lassoed to the cinematic world. Editing and camera are assigned invisible ways; they have to work without us getting to notice.

The Soviets changed all that very early in the game. Here a very world was assembled by the eye. There was no story, it was all a matter of calligraphic (dynamic overlapping) watching. Welles, and less famously Sternberg before him, unpacked these notions by letting it fall on the eye of the camera to join fragments together.

(this particular eye was first conceived by the Buddhist but that's another story altogether).

Now this is rumored to be the DP's project working under an alias, a Polish man who knows the camera. The opening shot exhibits masterful knowledge of Welles; a crane shot that establishes location by joining together many different planes of perspective. It would have been a film to watch with just this mode, that others like Argento and DePalma exercised in adventurous flourishes of spatial exploration.

It's actually a little more elaborate than that. We have two eyes instead of the one. The first is the killer's eye, tightly screwed and always at eye-level as he prowls around. Interior monologue plays out in voice-over, itself taken from the diaries of an actual killer, and meant to recast everything as internal space: victims are an invalid, an old woman and her daughter, each one mapping to a person that deeply wounded in the past as we find out. So we have exceedingly tormented soul spilled out and contorting physical space, very much like Zulawski practiced. Another Pole, another piece of the puzzle.

The second eye you will notice is always mounted on a crane and pulled upwards in steep ascends. A bird's eye far removed from human madness, which is the Buddhist eye of woodblock prints. To the film's credit, and this is a lot of its power for me, it remains abstract enough that we may use this perspective as we are inclined: is it a godless and uncaring or a merciful eye, pulling us from the carnage or skipping to the next?

- chaos-rampant

- Jan 27, 2012

- Permalink

Details

Box office

- Budget

- €400,000 (estimated)

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content