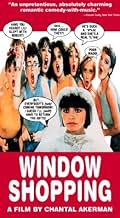

Employees and clients of a commercial gallery only live for love; they dream it, proclaim it, sing it and dance it. Experience the encounters, reunions, passions and disappointments of a mal... Read allEmployees and clients of a commercial gallery only live for love; they dream it, proclaim it, sing it and dance it. Experience the encounters, reunions, passions and disappointments of a malicious chorus of girls and a group of idle boys.Employees and clients of a commercial gallery only live for love; they dream it, proclaim it, sing it and dance it. Experience the encounters, reunions, passions and disappointments of a malicious chorus of girls and a group of idle boys.

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaCharles Denner's last film.

- ConnectionsReferences Gun Crazy (1950)

Featured review

'Golden Eighties' is a far cry, formally and thematically, from Akerman's films of the 70s--the rigorous studies, influenced by structuralist film, of domestic environment and gendered power dynamics in 'Jeanne Dielmann'; such dynamics as transposed onto loneliness, travel and connection in 'Les Rendez-Vous d'Anna'; the atomisation and anatomisation of the trope of lover's partings in 'Tout un Nuit'. Instead, this is a bona fide musical, set entirely in a shopping mall, with its vibrant colours, choreographed tightness, and tendency to burst into song every few minutes undeniably close to the sentimentalist cinema of Jacques Demy which might previously have seemed the antithesis to Akerman's cinematic rigour. With Demy's best-known films, 'Les Parapluies de Cherbourg' and 'Les Demoiselles de Rochefort', it shares the concern with romantic coincidence, reappearance, the chance meeting or missed opportunity the balance between an idealised lost or distance love (idealised because lost or distant) and a pragmatic relational compromise associated with career and with petit-bourgeois stability.

The plot's best enjoyed in its unfolding, rather than in drab summary: but briefly--Robert, son of cloth store owners, is in love with Lili, who runs the salon directly opposite, gifted to her by the married Mr. Jean, corrupt owner of mall property with a reputation as a gangster, and head-over-heels in love with her. His parents wish to take over the salon and turn it into an additional store, and Robert's desire gets in the way of their plans; meanwhile, Mado, an employee at the salon, shares a passion of her own for Robert. Into the mall steps an expat American--the long-lost lover of Robert's mother (played, in one of her final roles, by Delphine Seyrig), who nursed her back to health after she'd escaped the death camps (Akerman's concern with the genocidal traumas of European history figures even here), leaving her a dilemma of her own. Various pairings, proposals and betrayals later--along with plenty of generally brief songs, generally sung in chorus rather than as solo vehicles--Mr. Jean destroys Lili's store, Robert's parents get their expansion, his mother decides for longevity and security over the promise of revived romance, Robert himself decides to become a model capitalist, and all ends in a curious mixture of happiness, unhappiness and compromise that's given the feel, more than the content, of resolution.

Of the relatively little written on the film, reviewers seem to assume that Akerman must have distrusted or disliked the musical form as an inherently fallacious form--the epitome of Hollywood falsity. That hardly seems to be borne out by Akerman's own statements or by the film itself. This is, for sure, a criticism of the propaganda of fulfilment through commerce, patriarchy and romance narrative associated with a generalised sense of the American musical, but Akerman clearly loves the form, the material in itself. One can work with, and critique, cliche, whilst loving its forms, the joys and freedoms it affords--and, after all, the fixed camera and stark structural exercises of Akerman's early films are just as much 'artificial' affects as the elaborate choreography of the musical. In fact, what for Akerman retrospectively disappointed were the limitations placed on the film's scope--that she was not afforded the lavish canvas--particularly the spatial dimension--of bigger-budget musicals, and that what transpired is, in effect, a kind of chamber version, the piano reduction rather than the full score, as it were. Yet, though its ambitions were compromised by the circumstances of production--a confined set, limited crew, chamber ensemble rather than full orchestra, and so on--it makes of these its material. This is, after all, a film which doesn't leave the confines of a shopping mall--indeed, of a space of three stores within it--until the very final scene, where the characters emerge blinking into the sunlight and we realise with a shock that it's the middle of the day. And so the film turns the perpetual motion of dance and movement as expression of choreographed spontaneity, restricted freedom, into a kind of allegory for its entire operation: from the opening shots of stilettos moving across a floor to their echo in the scenes of illicit lovers caught in the act, feet visible beneath changing room curtains, and then to the filming of entire bodies, perpetually alone or jostling, connecting, touching, then moving away, all within the confines of a small set that functions like a kind of expanded version of the domestic interiors of 'Jeanne Dielmann' or the lesser-known, comedic 'L'Homme a la Valise'. Instead of static shots, there are quick cuts from person to person, a camera swooping to contain moving chorus lines, the frame filled almost to bursting with all-singing, all-dancing employees; central characters either get caught away in the crowd, shouting or singing their lines to each other while being jostled apart, or bemoan the empty space, devoid of customers in a time of recession. References to the economic crisis gradually build up as the film reaches its conclusion; Robert, the aimless romantic ('Romeo of the trousers', as the film's barbershop-quartet chorus put it, perpetually lounging at the bar) spouts the ethic of self-help, business practice, efficiency and competition ('expand, expand') learned from his father in parody sped-up tele-prompter speak; his father deploys a cynical metaphor of investment in love vs. the risks of passion while commiserating with the bride Robert has jilted; the beauty salon owned by a corrupt businessman as a pad for his lover is smashed up by said owner, who gets to trash the entire store, firing a gun, and seemingly escape any kind of legal consequences. Is the recession--and the allusions to the power of American global capital, investment and consumer patterns--the 'background' to the musical narrative, with its fast-moving plots and sub-plots, or is that musical the allegorical expression of it? In a sense, it's the same question as to the role of the Algerian war in Demy's 'Les Parapluies', but whereas the war there functions as absence, lacuna, the experience that can't be expressed, here recession and the language of economics, planning, expansion and the like unavoidably maps onto the (gendered) nature of love, even as it's perfectly possible to watch and enjoy the whole film for its surface pleasures--movement, orchestration (the mimicking of mall sounds in music and sound design), studies in group dynamics, rhymes alternately biting and bittersweet. Unjustly neglected.

The plot's best enjoyed in its unfolding, rather than in drab summary: but briefly--Robert, son of cloth store owners, is in love with Lili, who runs the salon directly opposite, gifted to her by the married Mr. Jean, corrupt owner of mall property with a reputation as a gangster, and head-over-heels in love with her. His parents wish to take over the salon and turn it into an additional store, and Robert's desire gets in the way of their plans; meanwhile, Mado, an employee at the salon, shares a passion of her own for Robert. Into the mall steps an expat American--the long-lost lover of Robert's mother (played, in one of her final roles, by Delphine Seyrig), who nursed her back to health after she'd escaped the death camps (Akerman's concern with the genocidal traumas of European history figures even here), leaving her a dilemma of her own. Various pairings, proposals and betrayals later--along with plenty of generally brief songs, generally sung in chorus rather than as solo vehicles--Mr. Jean destroys Lili's store, Robert's parents get their expansion, his mother decides for longevity and security over the promise of revived romance, Robert himself decides to become a model capitalist, and all ends in a curious mixture of happiness, unhappiness and compromise that's given the feel, more than the content, of resolution.

Of the relatively little written on the film, reviewers seem to assume that Akerman must have distrusted or disliked the musical form as an inherently fallacious form--the epitome of Hollywood falsity. That hardly seems to be borne out by Akerman's own statements or by the film itself. This is, for sure, a criticism of the propaganda of fulfilment through commerce, patriarchy and romance narrative associated with a generalised sense of the American musical, but Akerman clearly loves the form, the material in itself. One can work with, and critique, cliche, whilst loving its forms, the joys and freedoms it affords--and, after all, the fixed camera and stark structural exercises of Akerman's early films are just as much 'artificial' affects as the elaborate choreography of the musical. In fact, what for Akerman retrospectively disappointed were the limitations placed on the film's scope--that she was not afforded the lavish canvas--particularly the spatial dimension--of bigger-budget musicals, and that what transpired is, in effect, a kind of chamber version, the piano reduction rather than the full score, as it were. Yet, though its ambitions were compromised by the circumstances of production--a confined set, limited crew, chamber ensemble rather than full orchestra, and so on--it makes of these its material. This is, after all, a film which doesn't leave the confines of a shopping mall--indeed, of a space of three stores within it--until the very final scene, where the characters emerge blinking into the sunlight and we realise with a shock that it's the middle of the day. And so the film turns the perpetual motion of dance and movement as expression of choreographed spontaneity, restricted freedom, into a kind of allegory for its entire operation: from the opening shots of stilettos moving across a floor to their echo in the scenes of illicit lovers caught in the act, feet visible beneath changing room curtains, and then to the filming of entire bodies, perpetually alone or jostling, connecting, touching, then moving away, all within the confines of a small set that functions like a kind of expanded version of the domestic interiors of 'Jeanne Dielmann' or the lesser-known, comedic 'L'Homme a la Valise'. Instead of static shots, there are quick cuts from person to person, a camera swooping to contain moving chorus lines, the frame filled almost to bursting with all-singing, all-dancing employees; central characters either get caught away in the crowd, shouting or singing their lines to each other while being jostled apart, or bemoan the empty space, devoid of customers in a time of recession. References to the economic crisis gradually build up as the film reaches its conclusion; Robert, the aimless romantic ('Romeo of the trousers', as the film's barbershop-quartet chorus put it, perpetually lounging at the bar) spouts the ethic of self-help, business practice, efficiency and competition ('expand, expand') learned from his father in parody sped-up tele-prompter speak; his father deploys a cynical metaphor of investment in love vs. the risks of passion while commiserating with the bride Robert has jilted; the beauty salon owned by a corrupt businessman as a pad for his lover is smashed up by said owner, who gets to trash the entire store, firing a gun, and seemingly escape any kind of legal consequences. Is the recession--and the allusions to the power of American global capital, investment and consumer patterns--the 'background' to the musical narrative, with its fast-moving plots and sub-plots, or is that musical the allegorical expression of it? In a sense, it's the same question as to the role of the Algerian war in Demy's 'Les Parapluies', but whereas the war there functions as absence, lacuna, the experience that can't be expressed, here recession and the language of economics, planning, expansion and the like unavoidably maps onto the (gendered) nature of love, even as it's perfectly possible to watch and enjoy the whole film for its surface pleasures--movement, orchestration (the mimicking of mall sounds in music and sound design), studies in group dynamics, rhymes alternately biting and bittersweet. Unjustly neglected.

- How long is Golden Eighties?Powered by Alexa

Details

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content