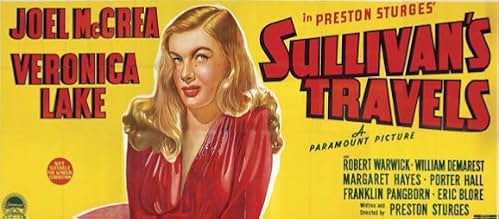

Hollywood director John L. Sullivan sets out to experience life as a homeless person in order to gain relevant life experience for his next movie.Hollywood director John L. Sullivan sets out to experience life as a homeless person in order to gain relevant life experience for his next movie.Hollywood director John L. Sullivan sets out to experience life as a homeless person in order to gain relevant life experience for his next movie.

- Awards

- 2 wins

Charles R. Moore

- Colored Chef

- (as Charles Moore)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaCinematographer John Seitz admired Preston Sturges' unconventional approach to his work. The opening scene comprised ten pages of dialogue to cover about four and a half minutes of screen time. It was scheduled for two complete days of shooting. On the morning of the first day, Seitz found Sturges inspecting the set with a viewfinder, looking for where he could cut the scene and change camera set-ups. Seitz dared him to do it all in one take. Never one to refuse a dare, Sturges took him up on it, although the nervous Seitz had never attempted to complete a two-day work schedule in one day. With the endorsement of McCrea and the rest of the actors, Sturges pressed on, determined to set a record. The first take was fine, but the camera wobbled a little in the tracking shot following the men from screening room to office, so they tried again. They did two or three takes at the most and that was it - two full days work by 11 a.m. on the first day, a feat that had the entire studio buzzing.

- GoofsWhen Sullivan and the Girl jump off the train and walk to the lunch stand, nothing is visible around the outside of the lunch stand--not a car, tree or anything. When Sullivan asks if the proprietor had seen a land yacht (a big RV), the proprietor points to the side and they look out the window and see the big land yacht parked there. Of course, if it had been there in the first place, Sullivan would have seen it right away and not gone into the lunch stand.

- Quotes

[last lines]

John L. Sullivan: There's a lot to be said for making people laugh. Did you know that that's all some people have? It isn't much, but it's better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan.

- Crazy creditsThe Paramount logo appears as a seal on a package.

The package is opened to reveal a book with the film title on it and the opening credits appear on pages in the book.

- ConnectionsFeatured in The Cinematographer (1951)

- SoundtracksSpring Song

(1844) (uncredited)

Written by Felix Mendelssohn

Played as part of the score when Sullivan starts his experiment

Reprised when he starts a second time

Featured review

Sturges' most daringly double-edged film, laced with bitter ironies. It is also arguably the most audacious film in Hollywood's (mainstream) history, audacious because it takes the kinds of risks that can so easily fall flat on their face, and right until the final image, as Sturges becomes increasingly ambitious and multi-layered, you wonder how long he can keep it up without getting ridiculous. It never does, but the film is so full of contradictions, tensions, suppressions, clanging lurches in tone - 'Travels' is ostensibly a comedy, and one of Hollywood's best, but the last twenty minutes are truly painful to watch, harrowing and not at all funny.

The overriding source of tension, of course, is the film itself, the plot, and the emotions that are supposed to be elicited. It is very difficult, and frequently impossible to gauge the tone of any one scene. Sometimes this is straightforward, as when information is deliberately withheld from the audience, it is asked to make a judgement, and then shown to be wrong, as in the scenes where the studio moguls claim a background of deprivation (which is historically plausible). This kind of comedy is familiar enough.

But what about the later montage of Sullivan and the Girl experiencing the 'reality' of poverty - are these scenes supposed to be genuine representation of poverty? Are they part of a wider satire on pious films like 'Grapes of Wrath', which dubiously aestheticise poverty - there are a lot of Expressionistic flourishes in this sequence? Are they a kind of abstract purgatory through which Sullivan finds spiritual understanding?

There is a big difference between the representation of poverty in this sequence and the one where Sullivan is attacked and sent to prison. But is one more 'authentic' than the other - the second one bravely rejects the view of 'noble' poverty, shows how it dehumanises people, turns them instinctual and brutal; but it also provides a neat moral, which suggests that if you do somebody wrong, you will be (horribly) punished for it. This realism, therefore, is as contrived as the first. Is this Sturges' point, that the good intentions of realism are always tainted by ideological assumptions, patronising good-will, or motives of elevation. This sense of artifice, of a film comprised of varying self-reflexive modes rather than a plausible narrative, runs through 'Travels', with characters talking about the film they're in as a plot - in direst danger, Sullivan acknowledges the need for a helluva twist which duly arrives, filmed in silent slapstick with barely concealed Sturges contempt (and did his friends seem terribly put out by his death?).

This would seem to uphold 'Travels'' ostensible theme, its celebration of comedy as a sugar with which to sweeten the harshness of reality. This is a very cynical view of comedy, and a highly manipulative, conservative one - distract an unhappy populace from the injustice of their lives. The best comedies - from 'Sherlock Jr' and 'Modern Times' to 'Playtime' and 'The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie' have always been about real life, encouraging their viewers to think harder about the society they live in, much more effectively than so-called naturalism.

'Travels' is no exception. It might be a celebration of comedy, but this is comedy a million miles from 'Ants in your Pants'. What other 40s film still manages to show the brutality of poverty, of the prison system, of race relations, the fate of young women in sexually voracious Hollywood (the Girl's ease with her body in the swimming pool scene speaks volumes), however we choose to read them? When Sullivan's determination at the end to continue making populist comedies is endorsed by the ringing laughter of the world's meek and suffering, the disjunction is grotesque. This is a man, on an airplane, completely removed from reality, surrounded by wealthy toadies. Those happy laughs could so easily be contemptuous guffaws, because what Sullivan wants to do, and Sturges hasn't, is hide the inequalities of capitalism, the system on which Hollywood thrives, and the flaws in which they would be only too happy to cover up with inanity. But to even suggest this is to fall into the 'Capra' trap mocked at the beginning.

This difficulty is what makes 'Travels' such a stunningly modern film - its shifts from sophisticated verbal wit to elaborate slapstick to blatant Carry On-like innuendo (the matronly sister dusting the bedpost after seeing a sweating, shirtless Sullivan work) to tragedy to hallucination and dream to satire foreshadows Melville and the New Wave, while the privileged rich man who cannot escape Hollywood would transmute into the guests who can't leave the house, or can't get dinner in later Bunuel films; or the film that begins with an end. The opening sequence takes off 'Citizen Kane'. The deadpan genderplay is quietly gobsmacking, and Veronica Lake as a (gorgeous) tramp would be alluded to by Jeanne Moreau in 'Jules et JIm'. But the joys are all Sturges', as he democratises comedy (see again that swimming pool sequence); I love in particular those glorious supporting actors: my favourite being the immortal Eric Blore and Robert Greig as Sullivan's servants.

The overriding source of tension, of course, is the film itself, the plot, and the emotions that are supposed to be elicited. It is very difficult, and frequently impossible to gauge the tone of any one scene. Sometimes this is straightforward, as when information is deliberately withheld from the audience, it is asked to make a judgement, and then shown to be wrong, as in the scenes where the studio moguls claim a background of deprivation (which is historically plausible). This kind of comedy is familiar enough.

But what about the later montage of Sullivan and the Girl experiencing the 'reality' of poverty - are these scenes supposed to be genuine representation of poverty? Are they part of a wider satire on pious films like 'Grapes of Wrath', which dubiously aestheticise poverty - there are a lot of Expressionistic flourishes in this sequence? Are they a kind of abstract purgatory through which Sullivan finds spiritual understanding?

There is a big difference between the representation of poverty in this sequence and the one where Sullivan is attacked and sent to prison. But is one more 'authentic' than the other - the second one bravely rejects the view of 'noble' poverty, shows how it dehumanises people, turns them instinctual and brutal; but it also provides a neat moral, which suggests that if you do somebody wrong, you will be (horribly) punished for it. This realism, therefore, is as contrived as the first. Is this Sturges' point, that the good intentions of realism are always tainted by ideological assumptions, patronising good-will, or motives of elevation. This sense of artifice, of a film comprised of varying self-reflexive modes rather than a plausible narrative, runs through 'Travels', with characters talking about the film they're in as a plot - in direst danger, Sullivan acknowledges the need for a helluva twist which duly arrives, filmed in silent slapstick with barely concealed Sturges contempt (and did his friends seem terribly put out by his death?).

This would seem to uphold 'Travels'' ostensible theme, its celebration of comedy as a sugar with which to sweeten the harshness of reality. This is a very cynical view of comedy, and a highly manipulative, conservative one - distract an unhappy populace from the injustice of their lives. The best comedies - from 'Sherlock Jr' and 'Modern Times' to 'Playtime' and 'The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie' have always been about real life, encouraging their viewers to think harder about the society they live in, much more effectively than so-called naturalism.

'Travels' is no exception. It might be a celebration of comedy, but this is comedy a million miles from 'Ants in your Pants'. What other 40s film still manages to show the brutality of poverty, of the prison system, of race relations, the fate of young women in sexually voracious Hollywood (the Girl's ease with her body in the swimming pool scene speaks volumes), however we choose to read them? When Sullivan's determination at the end to continue making populist comedies is endorsed by the ringing laughter of the world's meek and suffering, the disjunction is grotesque. This is a man, on an airplane, completely removed from reality, surrounded by wealthy toadies. Those happy laughs could so easily be contemptuous guffaws, because what Sullivan wants to do, and Sturges hasn't, is hide the inequalities of capitalism, the system on which Hollywood thrives, and the flaws in which they would be only too happy to cover up with inanity. But to even suggest this is to fall into the 'Capra' trap mocked at the beginning.

This difficulty is what makes 'Travels' such a stunningly modern film - its shifts from sophisticated verbal wit to elaborate slapstick to blatant Carry On-like innuendo (the matronly sister dusting the bedpost after seeing a sweating, shirtless Sullivan work) to tragedy to hallucination and dream to satire foreshadows Melville and the New Wave, while the privileged rich man who cannot escape Hollywood would transmute into the guests who can't leave the house, or can't get dinner in later Bunuel films; or the film that begins with an end. The opening sequence takes off 'Citizen Kane'. The deadpan genderplay is quietly gobsmacking, and Veronica Lake as a (gorgeous) tramp would be alluded to by Jeanne Moreau in 'Jules et JIm'. But the joys are all Sturges', as he democratises comedy (see again that swimming pool sequence); I love in particular those glorious supporting actors: my favourite being the immortal Eric Blore and Robert Greig as Sullivan's servants.

- the red duchess

- Sep 13, 2000

- Permalink

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $689,665 (estimated)

- Gross worldwide

- $10,249

- Runtime1 hour 30 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content