A man takes a job at an asylum with hopes of freeing his imprisoned wife.A man takes a job at an asylum with hopes of freeing his imprisoned wife.A man takes a job at an asylum with hopes of freeing his imprisoned wife.

Featured reviews

10quinolas

An old man works as a janitor in a mental hospital to be close to his wife who is a patient there and to try to get her out.

This is surely one of the most forgotten masterpieces of the silent era and an oddity in the history of Japanese cinema. Long thought lost, a print was found in the 70s and a music soundtrack added to it, which fits perfectly with the images. It might have been influenced by cabinet of doctor Caligary (director Kinugasa claimed he never saw the German film). However it surpasses it in style and in its more convincing (and chilly) portray of the inner mental state of the inmates in the asylum. To achieve this, the film makes use of every single film technique available at the time: multiple exposures and out of focus subjective point of view, tilted camera angles, fast and slow motion, expressionist lighting and superimpositions among others. It is also a very complicated film to follow, as it has not got intertitles.

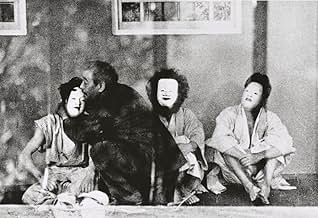

The film opens with a montage of shots of rain hitting the windows of the hospital, wind shaking trees and of thunder. The unsettling weather metaphors the mental condition of the patients and introduces one of the them: a former dancer. The combination of sounds produced by rain, wind and thunder serves as the music that incites the dancer to get into a frantic, almost hypnotic dance. In another sequence involving the same patient engaged in another frenzied dance, she is being watched by other inmates. Multiple exposures of the dancer represent the patients' point of view and their confused "view" of the world.

These are just two examples from this amazing film trying to represent the patients' subconscious and view of the "sane" world.

In three words A MUST SEE.

This is surely one of the most forgotten masterpieces of the silent era and an oddity in the history of Japanese cinema. Long thought lost, a print was found in the 70s and a music soundtrack added to it, which fits perfectly with the images. It might have been influenced by cabinet of doctor Caligary (director Kinugasa claimed he never saw the German film). However it surpasses it in style and in its more convincing (and chilly) portray of the inner mental state of the inmates in the asylum. To achieve this, the film makes use of every single film technique available at the time: multiple exposures and out of focus subjective point of view, tilted camera angles, fast and slow motion, expressionist lighting and superimpositions among others. It is also a very complicated film to follow, as it has not got intertitles.

The film opens with a montage of shots of rain hitting the windows of the hospital, wind shaking trees and of thunder. The unsettling weather metaphors the mental condition of the patients and introduces one of the them: a former dancer. The combination of sounds produced by rain, wind and thunder serves as the music that incites the dancer to get into a frantic, almost hypnotic dance. In another sequence involving the same patient engaged in another frenzied dance, she is being watched by other inmates. Multiple exposures of the dancer represent the patients' point of view and their confused "view" of the world.

These are just two examples from this amazing film trying to represent the patients' subconscious and view of the "sane" world.

In three words A MUST SEE.

Very few Japanese films exist from the silent period. In fact, statistics show that only 1% of around 7,000 productions are represented in the a catalogue of the silent cycle. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa's Kurutta Ippeji (also known as A Page of Madness) was thought lost (and perhaps forgotten) until he himself discovered a print in a warehouse in 1971. He diligently produced a new music soundtrack and re-released it. This is the first example of a silent film from Japan, and have to say that the world should be thankful that Kinugasa discovered this avant- garde little master work.

The film was produced with an avant garde group of artists, known as Shinkankak-ha (School of New Perceptions), an experimental art movement that rejected naturalism, or realism, and was highly influenced by European art movements such as Expressionism, Dada, and Cubism, and evidently uses the techniques found in Soviet Montage, particularly Sergei Eisenstein - fundamentally, as this project deals with madness, it would be easy to draw parallels with Robert Weine's seminal horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). What the art trope bring to this extreme nightmare are those exaggerated, pointed and alarmist movements like the expressionist acting styles being used in European film and stage work - but happens to find its own stylistic flourishes, and colloquial "voice" (for want of a better word).

Kurutta ippeji's simplistic story focuses on a man (Masuo Inoue) whom has taken a job as a janitor in an asylum, so that he may be close to his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who has been condemned. His aim is to aid in her escape from the dogmatic institution. However, when the break-out is orchestrated, her madness has enveloped her, and she is unwilling to leave with her husband. The couples daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits the asylum to advise her mother of her engagement, which leads to a maelstrom of fantastically abstract flashbacks, giving light to the reasons the mother is condemned.

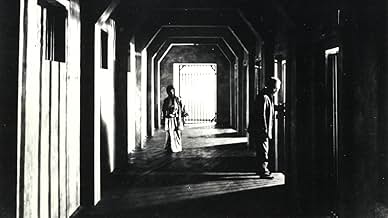

The films style is so incredibly complex and technically brilliant. In the opening sequence, the jarring compositions (both beautiful and haunting), superimposition's, and quick montage editing, creates an assault on the senses that is difficult to break away from - torrential rain falls the scenery in shots of the asylum, expressionist compositions of wind-battered tree branches clashing with windows, and the sight of a woman riddled in madness. The use of superimposition becomes greater as the film moves into crescendo, and these layers portray climatically the merger of madness and modernity. Do we witness the ghosts that haunt the corridors of the asylum? Or are these the devastating spectre's of modernity, and the destruction of tradition? An ironic speculation perhaps, considering the mechanics of cinema production and exhibition.

To a modern audience, silent cinema is often a difficult watch. This film is of particular note for this argument. Kurutta ippeji has no title cards describing dialogue, or internal action, which makes it difficult to follow at times. But as with all 1920's Japanese cinema, the films were always accompanied by narration - a storyteller known colloquially as a benshi. But this small infraction does not hamper an incredibly dazzling piece of early experimental cinema, and one that should be viewed by any film enthusiast, at least for posterity - if not for a formative education on the stylistic diversity of film as art.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

The film was produced with an avant garde group of artists, known as Shinkankak-ha (School of New Perceptions), an experimental art movement that rejected naturalism, or realism, and was highly influenced by European art movements such as Expressionism, Dada, and Cubism, and evidently uses the techniques found in Soviet Montage, particularly Sergei Eisenstein - fundamentally, as this project deals with madness, it would be easy to draw parallels with Robert Weine's seminal horror film Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). What the art trope bring to this extreme nightmare are those exaggerated, pointed and alarmist movements like the expressionist acting styles being used in European film and stage work - but happens to find its own stylistic flourishes, and colloquial "voice" (for want of a better word).

Kurutta ippeji's simplistic story focuses on a man (Masuo Inoue) whom has taken a job as a janitor in an asylum, so that he may be close to his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who has been condemned. His aim is to aid in her escape from the dogmatic institution. However, when the break-out is orchestrated, her madness has enveloped her, and she is unwilling to leave with her husband. The couples daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits the asylum to advise her mother of her engagement, which leads to a maelstrom of fantastically abstract flashbacks, giving light to the reasons the mother is condemned.

The films style is so incredibly complex and technically brilliant. In the opening sequence, the jarring compositions (both beautiful and haunting), superimposition's, and quick montage editing, creates an assault on the senses that is difficult to break away from - torrential rain falls the scenery in shots of the asylum, expressionist compositions of wind-battered tree branches clashing with windows, and the sight of a woman riddled in madness. The use of superimposition becomes greater as the film moves into crescendo, and these layers portray climatically the merger of madness and modernity. Do we witness the ghosts that haunt the corridors of the asylum? Or are these the devastating spectre's of modernity, and the destruction of tradition? An ironic speculation perhaps, considering the mechanics of cinema production and exhibition.

To a modern audience, silent cinema is often a difficult watch. This film is of particular note for this argument. Kurutta ippeji has no title cards describing dialogue, or internal action, which makes it difficult to follow at times. But as with all 1920's Japanese cinema, the films were always accompanied by narration - a storyteller known colloquially as a benshi. But this small infraction does not hamper an incredibly dazzling piece of early experimental cinema, and one that should be viewed by any film enthusiast, at least for posterity - if not for a formative education on the stylistic diversity of film as art.

www.the-wrath-of-blog.blogspot.com

10mjneu59

Film history has been negligent in recognizing this landmark silent drama, made in 1926 by pioneering Japanese director Teinosuke Kinugasa, but unknown until 1971, when a surviving print was (literally) unearthed in the director's garden shed. The film was produced in an isolated creative environment far removed from any foreign influence, but is nevertheless a masterpiece of imagery and editing, revealing a stunning visual flair and employing montage techniques as skillfully as anyone since Eisenstein. It tells a powerful, hallucinatory story of a janitor in an insane asylum who wants desperately to help his inmate wife after she attempts suicide, and like Murnau's 'The Last Laugh' unfolds without the crutch of intertitles. The film has aged remarkable little after the better part of a century in limbo, but since its belated rediscovery has yet to earn the acclaim and evaluation it deserves.

Kurutta ippêji (1926)

*** (out of 4)

Bizarre Japanese horror film has a man taking a janitor job at an asylum so that he can be closer to his wife who was committed after trying to kill their child. Had Luis Bunuel been bore in Japan and started making movies in 1926 then I'm guessing the final product would have came out looking like this thing. Lost for decades, it's easy to see why this film was never discovered but now that it's making its way around, it seems like this is destined to become something of a cult favorite to silent and horror fans. There's no straight story being told here, instead it's more avant-garde as we get all sorts of surreal images. We get the basic story but everything else is either told in flashback or through extra fast editing that helps build up the insanity of the lead character. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa really wants to get inside the mind of the insane and I think he does a pretty good job with it. At just 59-minutes the film moves at a pretty fast rate and a lot of this can be credited to the editing. I thought that the editing was the real star of the movie as it's done in such a fashion that you often see something but then you question what it was that you actually saw. You also have to try and keep up with what's going on and everything is happening so fast that you can see that the director was trying to use this to make the viewer feel what the characters were feeling being the asylum walls. There aren't any intertitles, which just adds to the visual image and the music score (done in the 70s) fits the film very well.

*** (out of 4)

Bizarre Japanese horror film has a man taking a janitor job at an asylum so that he can be closer to his wife who was committed after trying to kill their child. Had Luis Bunuel been bore in Japan and started making movies in 1926 then I'm guessing the final product would have came out looking like this thing. Lost for decades, it's easy to see why this film was never discovered but now that it's making its way around, it seems like this is destined to become something of a cult favorite to silent and horror fans. There's no straight story being told here, instead it's more avant-garde as we get all sorts of surreal images. We get the basic story but everything else is either told in flashback or through extra fast editing that helps build up the insanity of the lead character. Director Teinosuke Kinugasa really wants to get inside the mind of the insane and I think he does a pretty good job with it. At just 59-minutes the film moves at a pretty fast rate and a lot of this can be credited to the editing. I thought that the editing was the real star of the movie as it's done in such a fashion that you often see something but then you question what it was that you actually saw. You also have to try and keep up with what's going on and everything is happening so fast that you can see that the director was trying to use this to make the viewer feel what the characters were feeling being the asylum walls. There aren't any intertitles, which just adds to the visual image and the music score (done in the 70s) fits the film very well.

...from director Teinosuke Kinugasa. A man (Masuo Inoue) works as a janitor at a mental asylum in order to be near his wife (Yoshie Nakagawa), who is a patient. The man's daughter (Ayako Iijima) is to be married soon, and questions of attendance are making things difficult for the man.

This meager narrative provides the framework for a lot of flash-cut editing, strobing visual tricks, and experimental cinema. This isn't interesting as a traditional story (at least, not the existing version, which is said to be missing nearly a third of its original footage), but rather in depicting madness and inner turmoil in a visual fashion. Even the usual silent film intertitles are absent, rendering the film a purely visual experience. The score that was used on the version I watched seemed like it was suited for a late 1960s acid party. The original release was said to have had a narrator and traditional Japanese music accompaniment. What I saw was still an interesting viewing, much of it closer to experimental films from the 1960s than what I'm used to seeing from the 1920s.

This meager narrative provides the framework for a lot of flash-cut editing, strobing visual tricks, and experimental cinema. This isn't interesting as a traditional story (at least, not the existing version, which is said to be missing nearly a third of its original footage), but rather in depicting madness and inner turmoil in a visual fashion. Even the usual silent film intertitles are absent, rendering the film a purely visual experience. The score that was used on the version I watched seemed like it was suited for a late 1960s acid party. The original release was said to have had a narrator and traditional Japanese music accompaniment. What I saw was still an interesting viewing, much of it closer to experimental films from the 1960s than what I'm used to seeing from the 1920s.

Did you know

- TriviaThis film was deemed lost for more than forty years, but it was rediscovered by its director, Teinosuke Kinugasa, in a rice cans in 1971.

- Alternate versionsReissued in Japan in 1973 with musical score replacing original benshi.

- ConnectionsFeatured in The Story of Film: An Odyssey: The Golden Age of World Cinema (2011)

- How long is A Page of Madness?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- ¥20,000 (estimated)

- Runtime1 hour 10 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content