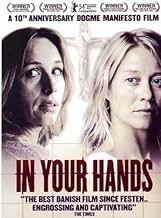

Forbrydelser

- 2004

- 1h 41min

VALUTAZIONE IMDb

6,7/10

1201

LA TUA VALUTAZIONE

Aggiungi una trama nella tua linguaAnna begins as a rookie chaplain in a women's prison and meets an inmate who can perform miracles and cure drug addicts with a touch. She says Anna is pregnant and a test confirms it. But no... Leggi tuttoAnna begins as a rookie chaplain in a women's prison and meets an inmate who can perform miracles and cure drug addicts with a touch. She says Anna is pregnant and a test confirms it. But not all is well.Anna begins as a rookie chaplain in a women's prison and meets an inmate who can perform miracles and cure drug addicts with a touch. She says Anna is pregnant and a test confirms it. But not all is well.

- Premi

- 8 vittorie e 16 candidature totali

Jens Zacho Böye

- Betjent

- (as Jens Zacho Boye)

Trama

Lo sapevi?

- QuizThis film was made to celebrate the ten year anniversary of Dogme95 movement.

- ConnessioniFeatured in Pigerne bag 'Forbrydelser' (2004)

Recensione in evidenza

About ten years ago, a group of Danish filmmakers started the Dogme school of film-making, that inflicted a self-imposed discipline on its adherents, including no artificial leaps of time and space, no special effects or soundtracks that weren't actually created on set, hand-held cameras only, no superficial plot enhancements (like murders) and so on. It was a reaction partly against the 'auteur' school where a director stamped his personality on a film, but mostly against the excesses and decadence of Hollywood, as the founders felt that filmmakers were in danger of losing sight of the craft of film-making in a world where a film's value was dictated by accountants, marketing people, big names, and people and technology that was external to the process itself. The creators of Dogme never intended it as a philosophy to be put on a pedestal, but simply as an experiment, one of any number, that could create better film-making. In Your Hands is reportedly the last film to be made under the strict auspices of Dogme.

Our main protagonist is Anna (played by Ann Eleonora Jorgenson), a newly qualified pastor, who takes up her first appointment in a women's prison. One of the inmates is reputed to have 'healing hands' or is maybe psychic. The emotional crises that develop are ones between faith and spirituality, as well as attitudes to abortion and love versus duty.

Dogme's great strength has been the way it lends itself to naturalistic, almost documentary-like acting, and then, once the audience has completely bought in and sees the characters as totally lifelike, being able to shock us with revelations that could be frivolous in any others hands - but become cause for soul searching when we are confronted with them as part of 'normal' life. There have been many failures often due to poor acting and poor script (Dogme is a discipline to avoid the excesses pitfalls of market-driven cinema, not a ready built recipe for success). But its best examples have always shocked us by making us ask how on earth a 'real' person copes. In Festen (The Celebration), we get to know and like a normal family that have a big reunion grand dinner . . . at the height of the joie de vivre, when suddenly one of the family is accused of abusing one of the others present (now an adult) as a child, it is difficult for the audience to cope with wondering how exactly the rest of the family should act. In Idioterne (The Idiots), a group of drop-outs have fun or 'celebrate their inner idiot' by acting like mentally ill people. The problem the serious audience has is not whether such material is a suitable subject for a movie but whether they are able to come to terms with their own feelings about it when it is portrayed so realistically.

A question posed by these films that is also posed by In Your Hands is, what do we do when someone we like or respect is also a source of wrongdoing? And what of our judgement? Are we free to judge as if we were perfect can we forgive ourselves for being only human and if so, where do we draw the line on what is acceptable in our own judgements and our own aspiration to become better? The process of 'becoming who we are', individually, also draws a nice parallel to the process of film-making which, at the level of Dogme, is reduced to itself, for better or worse.

One of the great strengths of In Your Hands is the acting, particularly Jorgenson. She just wants to be a pastor, be a reasonably nice person, do her job, get on with her relationship etc. She is not prepared for the difficult tests of faith that come her way and neither are we. When she cries, we want to as well, because we feel as trapped as she is by our difficulty in finding a suitable answer to her perfectly reasonable dilemma. But it is her struggle with her problem, her determination to find a decent solution (even if she fails abysmally at times) that make us buy into her character emotionally, in the hope that she will find the right course even where we fail. The gut wrenching performances serve a purpose that goes beyond entertainment they make us ask hypothetically how each of us (as a normal human as is the character) would struggle to answer such difficult problems if they arose, and it is this contribution to situational ethics by means of fictionalised analogy (whether in theatre, literature, poetry, opera or soap opera) that is also one of the defining characteristics (one of many) by which we can identify certain types of art as art and one (of many) reasons that art contributes to a better society. Dogme may have served its purpose, but it has served it well.

Our main protagonist is Anna (played by Ann Eleonora Jorgenson), a newly qualified pastor, who takes up her first appointment in a women's prison. One of the inmates is reputed to have 'healing hands' or is maybe psychic. The emotional crises that develop are ones between faith and spirituality, as well as attitudes to abortion and love versus duty.

Dogme's great strength has been the way it lends itself to naturalistic, almost documentary-like acting, and then, once the audience has completely bought in and sees the characters as totally lifelike, being able to shock us with revelations that could be frivolous in any others hands - but become cause for soul searching when we are confronted with them as part of 'normal' life. There have been many failures often due to poor acting and poor script (Dogme is a discipline to avoid the excesses pitfalls of market-driven cinema, not a ready built recipe for success). But its best examples have always shocked us by making us ask how on earth a 'real' person copes. In Festen (The Celebration), we get to know and like a normal family that have a big reunion grand dinner . . . at the height of the joie de vivre, when suddenly one of the family is accused of abusing one of the others present (now an adult) as a child, it is difficult for the audience to cope with wondering how exactly the rest of the family should act. In Idioterne (The Idiots), a group of drop-outs have fun or 'celebrate their inner idiot' by acting like mentally ill people. The problem the serious audience has is not whether such material is a suitable subject for a movie but whether they are able to come to terms with their own feelings about it when it is portrayed so realistically.

A question posed by these films that is also posed by In Your Hands is, what do we do when someone we like or respect is also a source of wrongdoing? And what of our judgement? Are we free to judge as if we were perfect can we forgive ourselves for being only human and if so, where do we draw the line on what is acceptable in our own judgements and our own aspiration to become better? The process of 'becoming who we are', individually, also draws a nice parallel to the process of film-making which, at the level of Dogme, is reduced to itself, for better or worse.

One of the great strengths of In Your Hands is the acting, particularly Jorgenson. She just wants to be a pastor, be a reasonably nice person, do her job, get on with her relationship etc. She is not prepared for the difficult tests of faith that come her way and neither are we. When she cries, we want to as well, because we feel as trapped as she is by our difficulty in finding a suitable answer to her perfectly reasonable dilemma. But it is her struggle with her problem, her determination to find a decent solution (even if she fails abysmally at times) that make us buy into her character emotionally, in the hope that she will find the right course even where we fail. The gut wrenching performances serve a purpose that goes beyond entertainment they make us ask hypothetically how each of us (as a normal human as is the character) would struggle to answer such difficult problems if they arose, and it is this contribution to situational ethics by means of fictionalised analogy (whether in theatre, literature, poetry, opera or soap opera) that is also one of the defining characteristics (one of many) by which we can identify certain types of art as art and one (of many) reasons that art contributes to a better society. Dogme may have served its purpose, but it has served it well.

- Chris_Docker

- 5 mag 2005

- Permalink

I più visti

Accedi per valutare e creare un elenco di titoli salvati per ottenere consigli personalizzati

- How long is In Your Hands?Powered by Alexa

Dettagli

- Data di uscita

- Paese di origine

- Sito ufficiale

- Lingua

- Celebre anche come

- In Your Hands

- Luoghi delle riprese

- Aziende produttrici

- Vedi altri crediti dell’azienda su IMDbPro

Botteghino

- Lordo in tutto il mondo

- 10.011 USD

Contribuisci a questa pagina

Suggerisci una modifica o aggiungi i contenuti mancanti

Divario superiore

By what name was Forbrydelser (2004) officially released in India in English?

Rispondi