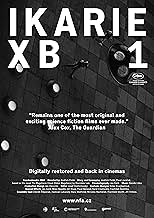

Ikarie XB 1

- 1963

- 1h 26m

ÉVALUATION IMDb

6,9/10

3,1 k

MA NOTE

Nous sommes en 2163. Le vaisseau spatial Ikarie XB 1 part pour un long voyage à travers l'univers, à la recherche de la vie sur les planètes d'Alpha du Centaure.Nous sommes en 2163. Le vaisseau spatial Ikarie XB 1 part pour un long voyage à travers l'univers, à la recherche de la vie sur les planètes d'Alpha du Centaure.Nous sommes en 2163. Le vaisseau spatial Ikarie XB 1 part pour un long voyage à travers l'univers, à la recherche de la vie sur les planètes d'Alpha du Centaure.

- Prix

- 1 victoire au total

Histoire

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesThe music played on piano after the derelict ship explodes is "Part One: Introduction" from "King David", aka "Le Roi David," composed by Arthur Honegger.

- Autres versionsSPOILER: For the American release, titled "Voyage to the End of the Universe," American International Pictures cut the film up, changing a number of things:

- Approximately 26 minutes of footage were removed (including a sequence in a man-made flying saucer carrying dead capitalists, nerve gas and an atomic bomb).

- The story was changed substantially, the ship's flight direction reversed (making it an alien ship traveling to Earth), and the Statue of Liberty pasted into the final shot.

- The cast and staff's names in the credits were altered significantly to look like English.

Commentaire en vedette

Still relatively unfamiliar to western audiences, Ikarie XB 1 is an example of east European science fiction cinema on a fairly ambitious scale deserving of wider appreciation. Usually it's been only seen in a butchered edition created Stateside - duly shorn of a plot strand, dubbed with a different ending, with a dumb title.

With the benefit of hindsight, a lot of the original seems familiar. With its clean interior ship design, crew neck uniforms all round, glide doors, shiny deck flooring as well as a 15-year mission to seek out new life, Ikarie may have given later pause for thought for a certain Gene Roddenberry. Genre fans will also note that, during the first big set piece, the crew are startled by an unexpected alarm and deviate from their mission to investigate a derelict spacecraft - events which end with a nuclear detonation in space. Add to this the changes wrought by the American bastardisation of Voyage To The End Of The Universe, that included an ending which anticipates Planet of the Apes, as well as its possible inspiration to Kubrick when planning 2001, and Ikarie certainly offers much of interest. Not to mention its own borrowings eg Ikarie's robot Patrick, inspired by Forbidden Planet (1956)

Polák's was also responsible for an intriguing Nazi time travelling movie, with a small cult on its own account, Tomorrow I'll Wake Up And Scald Myself With Tea, made in the late 1970s. Less idiosyncratic than this, one imagines, Ikarie is much more serious in tone, set mostly aboard a roomy spacecraft, crewed by 40, dispatched to discover if there is any life on Alpha Centauri. A feeling of worthwhile isolation permeates this journey, with none of the trivial, trials and stresses one expects from space dramas made closer to home at this time, where mad scientists lurk, robots lumber threateningly or spacewomen defer to their mates. Missing too is the pseudo technical claptrap which lumbers much American SF, then or now. Ikarie's hardware exists mainly in the background, without need of explanation. The film expects us to take its conspicuous 22nd century advances just as seen, being concerned more with sociology than technology.

Ikarie features a harmonious society in miniature, shown in a series of interactions aboard, even down to the calm acceptance of on board pregnancy - an adult theme incidentally completely excised in the American version. In such an hospitable environment, even the mad can be talked round without violence, as in the case of Michael (Otto Lackovic) who, affected by radiation and in a disastrous manoeuvre, wants to turn the ship back to Earth. That the only real threat the crew face is an external one is significant, and also primes the dramatic moment that begins the narrative. A flash-forward to when (infected by the same source, as we learn later), one of the crew is wandering, bewildered and aggressive, through the ship. "Earth is gone," he says. "Earth never existed." But he's not beyond help from his peers. Here the deluded or mad in space are not assumed lost, such as we might see in such recent American films as Event Horizon, but taken back and with promise of cure at that.

Critics have contrasted these shipboard mores to the signs of capitalist degeneracy confronting those who board the 'Tornado', the derelict space station from 1987 unexpectedly encountered en route. Here, amidst the dark clutter of its interior, are found signs of gambling and money, coded elements of capitalist speculation, just as fatal as the death gas and nuclear warheads also there. For those who explore it, the Tornado reflects a place thought left behind, both geographically and politically. "We have discovered the 20th century," says one dismayed crewman. The determined self destruction encountered by those who board the derelict recalls one of TV's original Star Trek shows, and those found died as result of a selfish fight for survival. The signs of a corrupt political system fall exposed with as much horror as does (in a notable moment) the skin off the Tornado captain's face.

This, and then the debilitating effects of rays that emanate from a hitherto unknown black star are the two principal threats facing the crew. How they finally overcome this last hurdle is part of the end of the quest. Without giving too much away, it is sufficient to say that the close of the film, the ship's long anticipated arrival at Alpha Centauri's 'white planet', brings a sequence both uplifting and brief, carrying over the theme of mutually beneficial cooperation. But viewers today may find less interest in the ending than the scenes that have preceded it. It's the Ikarie crew's social or dutiful pairings, even to the point of bringing each other flowers, or taking showers together, which lay at the heart of the film, rather than any encounter of a new civilisation and the socialist message entailed. Whilst in basic narrative terms the 'white planet' brings closure, our attentions have for long been focused elsewhere, in scenes such as the notable dance sequence. Through the hypnotic rhythms of Zdenek Liska's striking score, the astronauts take part in something akin to a weird 22nd century disco, their slow somnambulistic movements reassuring while also slightly disturbing. Reassuring, as we can see the crew reacting together as one social unit, even after the inevitable trials of months in space; disturbing because it is all so emotionless and controlled. Such ambiguous group occasions beg questions we really want answered. Are they really happy? Or does the Earth we thought we recognised in them no longer exist?

The Czech originated disc I have seen offers a splendid widescreen transfer of the movie with English subtitles. Most of the extras are unfortunately not subtitled, but there's a chance to see some sample scenes from the American International version, to give an idea of how the original was changed as well as a stills gallery.

With the benefit of hindsight, a lot of the original seems familiar. With its clean interior ship design, crew neck uniforms all round, glide doors, shiny deck flooring as well as a 15-year mission to seek out new life, Ikarie may have given later pause for thought for a certain Gene Roddenberry. Genre fans will also note that, during the first big set piece, the crew are startled by an unexpected alarm and deviate from their mission to investigate a derelict spacecraft - events which end with a nuclear detonation in space. Add to this the changes wrought by the American bastardisation of Voyage To The End Of The Universe, that included an ending which anticipates Planet of the Apes, as well as its possible inspiration to Kubrick when planning 2001, and Ikarie certainly offers much of interest. Not to mention its own borrowings eg Ikarie's robot Patrick, inspired by Forbidden Planet (1956)

Polák's was also responsible for an intriguing Nazi time travelling movie, with a small cult on its own account, Tomorrow I'll Wake Up And Scald Myself With Tea, made in the late 1970s. Less idiosyncratic than this, one imagines, Ikarie is much more serious in tone, set mostly aboard a roomy spacecraft, crewed by 40, dispatched to discover if there is any life on Alpha Centauri. A feeling of worthwhile isolation permeates this journey, with none of the trivial, trials and stresses one expects from space dramas made closer to home at this time, where mad scientists lurk, robots lumber threateningly or spacewomen defer to their mates. Missing too is the pseudo technical claptrap which lumbers much American SF, then or now. Ikarie's hardware exists mainly in the background, without need of explanation. The film expects us to take its conspicuous 22nd century advances just as seen, being concerned more with sociology than technology.

Ikarie features a harmonious society in miniature, shown in a series of interactions aboard, even down to the calm acceptance of on board pregnancy - an adult theme incidentally completely excised in the American version. In such an hospitable environment, even the mad can be talked round without violence, as in the case of Michael (Otto Lackovic) who, affected by radiation and in a disastrous manoeuvre, wants to turn the ship back to Earth. That the only real threat the crew face is an external one is significant, and also primes the dramatic moment that begins the narrative. A flash-forward to when (infected by the same source, as we learn later), one of the crew is wandering, bewildered and aggressive, through the ship. "Earth is gone," he says. "Earth never existed." But he's not beyond help from his peers. Here the deluded or mad in space are not assumed lost, such as we might see in such recent American films as Event Horizon, but taken back and with promise of cure at that.

Critics have contrasted these shipboard mores to the signs of capitalist degeneracy confronting those who board the 'Tornado', the derelict space station from 1987 unexpectedly encountered en route. Here, amidst the dark clutter of its interior, are found signs of gambling and money, coded elements of capitalist speculation, just as fatal as the death gas and nuclear warheads also there. For those who explore it, the Tornado reflects a place thought left behind, both geographically and politically. "We have discovered the 20th century," says one dismayed crewman. The determined self destruction encountered by those who board the derelict recalls one of TV's original Star Trek shows, and those found died as result of a selfish fight for survival. The signs of a corrupt political system fall exposed with as much horror as does (in a notable moment) the skin off the Tornado captain's face.

This, and then the debilitating effects of rays that emanate from a hitherto unknown black star are the two principal threats facing the crew. How they finally overcome this last hurdle is part of the end of the quest. Without giving too much away, it is sufficient to say that the close of the film, the ship's long anticipated arrival at Alpha Centauri's 'white planet', brings a sequence both uplifting and brief, carrying over the theme of mutually beneficial cooperation. But viewers today may find less interest in the ending than the scenes that have preceded it. It's the Ikarie crew's social or dutiful pairings, even to the point of bringing each other flowers, or taking showers together, which lay at the heart of the film, rather than any encounter of a new civilisation and the socialist message entailed. Whilst in basic narrative terms the 'white planet' brings closure, our attentions have for long been focused elsewhere, in scenes such as the notable dance sequence. Through the hypnotic rhythms of Zdenek Liska's striking score, the astronauts take part in something akin to a weird 22nd century disco, their slow somnambulistic movements reassuring while also slightly disturbing. Reassuring, as we can see the crew reacting together as one social unit, even after the inevitable trials of months in space; disturbing because it is all so emotionless and controlled. Such ambiguous group occasions beg questions we really want answered. Are they really happy? Or does the Earth we thought we recognised in them no longer exist?

The Czech originated disc I have seen offers a splendid widescreen transfer of the movie with English subtitles. Most of the extras are unfortunately not subtitled, but there's a chance to see some sample scenes from the American International version, to give an idea of how the original was changed as well as a stills gallery.

- FilmFlaneur

- 29 juill. 2008

- Lien permanent

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et surveiller les recommandations personnalisées

- How long is Voyage to the End of the Universe?Propulsé par Alexa

Détails

- Date de sortie

- Pays d’origine

- Langue

- Aussi connu sous le nom de

- Voyage to the End of the Universe

- Lieux de tournage

- société de production

- Consultez plus de crédits d'entreprise sur IMDbPro

Box-office

- Brut – à l'échelle mondiale

- 2 130 $ US

- Durée1 heure 26 minutes

- Couleur

- Mixage

- Rapport de forme

- 2.35 : 1

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was Ikarie XB 1 (1963) officially released in India in English?

Répondre