PUNTUACIÓN EN IMDb

6,8/10

7,1 mil

TU PUNTUACIÓN

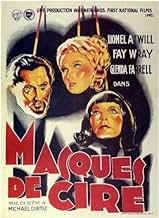

En un museo de cera, un curador enmascarado transforma a la gente en estatuas y busca a su siguiente María Antonieta.En un museo de cera, un curador enmascarado transforma a la gente en estatuas y busca a su siguiente María Antonieta.En un museo de cera, un curador enmascarado transforma a la gente en estatuas y busca a su siguiente María Antonieta.

Thomas E. Jackson

- Detective

- (as Thomas Jackson)

Bull Anderson

- Janitor

- (sin acreditar)

Frank Austin

- Winton's Valet

- (sin acreditar)

Max Barwyn

- Museum Visitor

- (sin acreditar)

Wade Boteler

- Ambrose

- (sin acreditar)

Argumento

¿Sabías que...?

- CuriosidadesThis film was produced before the Production Code. When it was remade 20 years later, as Los crímenes del museo de cera (1953), all references to drug use were removed, and a character was changed from a junkie to an alcoholic.

- PifiasIvan Igor says that Jean Paul Marat's assassin, Charlotte Corday, was his mistress. Not so - they had never met until she came to his office posing as a courier and quickly stabbed him to death. After her execution a few days later, she was found to be virgo intacta.

- Versiones alternativasThis film was shot in two versions. One camera unit shot the film in two-color Technicolor. A second camera unit shot the scenes at the same time in black and white. The black and white version was meant for theaters who could not afford the higher rental cost of the color prints.

- ConexionesEdited into Ante todo, mujer (1974)

Reseña destacada

The early 1930s was perhaps the only real golden age of the horror. It didn't really introduce much that was new to the genre, but it contributed many of its unrivalled classics. The horrors of this time have a certain quality whereby they on the one hand revel in all the clichés of the form, whilst at the same time twisting and stretching them with all the playful inventiveness typical of the early sound era.

Take for example the fact that Mystery of the Wax Museum is filmed in two-strip Technicolor. Colour was a rarity at the time and was mostly used to augment the splendour of the many depression-era musicals, and yet the two-strip process seems ideally suited to making this picture what it is. Cinematographer Ray Rennahan (later to receive Academy Awards for Gone with the Wind and Blood and Sand), rather than splurging on a multitude of shades, seems to view colour filming in dual terms of light and dark tone. What you see on the screen bares little resemblance to the usual bland red and green of two-strip. Instead figures tend to be picked out in warm reddish-yellow tones against the gloom, which by contrast almost takes on the blue that was impossible for this format. This warm hue which bathes people and sculpture alike brings to mind blood, fire and wax and is just as eerie as stark monochrome.

Director Michael Curtiz had a real feel for the macabre, as well as a slightly misanthropic tendency to view props and players as being of more or less equal importance. This ironically works in Wax Museum's favour, as Curtiz brings out the various waxworks as characters in their own right. The opening shot is almost like a spoof of the elaborate crowd sweeps with which Curtiz would open pictures like Angels with Dirty Faces and Casablanca, tracking through the lifeless sculptures as if it were some frozen street-scene, eventually alighting on Lionel Atwill like one of the figures come to life. Curtiz also encourages relaxed, understated performances, far more so than was the norm at the time, especially for a director of European origin. Perhaps he didn't want the actors upstaging their inanimate counterparts Whatever his reasoning, the low-key performances are ideal for the creepy tone of this picture. Lionel Atwill gives one of his most believable turns, presenting Igor as a generally mild-mannered artist, giving a vague, delusional quality to his occasional lapses into anger. His gentle eastern-European accent is enough to remind us of his foreign beginnings without turning him into a vulgar stereotype. The overt hamminess of Bela Lugosi may be massively more fun, but Atwill wins out in the stakes of genuine scariness. And Atwill's success here has much to do with the kind of horror it is he appears in. As we see in Psycho or Silence of the Lambs, a cruel and unusual human mind is a far more frightening prospect than a mere monster.

The other great player here is Glenda Farrell, giving an engaging and likable spin on the wise-cracking go-getting heroine, a character of a sort she would later reprise in the Torchy Blane serial. She may get third billing, just under the better-known Fay Wray, but Farrell is the true lead of this horror-drama, and this in itself is part of the beguiling oddness of Mystery of the Wax Museum. Wray is the then-obligatory female victim, but from the gaggle of male good-guys no-one emerges as her heroic saviour. In a refreshing twist it is this smart sassy woman who takes on the eponymous mystery. The strong conventions of the day around women and action may mean Farrell is excused from the final rescue sequence, but the cunning and determination of her character mean we can view her as a forerunner of Ellen Ripley and Clarice Starling.

Take for example the fact that Mystery of the Wax Museum is filmed in two-strip Technicolor. Colour was a rarity at the time and was mostly used to augment the splendour of the many depression-era musicals, and yet the two-strip process seems ideally suited to making this picture what it is. Cinematographer Ray Rennahan (later to receive Academy Awards for Gone with the Wind and Blood and Sand), rather than splurging on a multitude of shades, seems to view colour filming in dual terms of light and dark tone. What you see on the screen bares little resemblance to the usual bland red and green of two-strip. Instead figures tend to be picked out in warm reddish-yellow tones against the gloom, which by contrast almost takes on the blue that was impossible for this format. This warm hue which bathes people and sculpture alike brings to mind blood, fire and wax and is just as eerie as stark monochrome.

Director Michael Curtiz had a real feel for the macabre, as well as a slightly misanthropic tendency to view props and players as being of more or less equal importance. This ironically works in Wax Museum's favour, as Curtiz brings out the various waxworks as characters in their own right. The opening shot is almost like a spoof of the elaborate crowd sweeps with which Curtiz would open pictures like Angels with Dirty Faces and Casablanca, tracking through the lifeless sculptures as if it were some frozen street-scene, eventually alighting on Lionel Atwill like one of the figures come to life. Curtiz also encourages relaxed, understated performances, far more so than was the norm at the time, especially for a director of European origin. Perhaps he didn't want the actors upstaging their inanimate counterparts Whatever his reasoning, the low-key performances are ideal for the creepy tone of this picture. Lionel Atwill gives one of his most believable turns, presenting Igor as a generally mild-mannered artist, giving a vague, delusional quality to his occasional lapses into anger. His gentle eastern-European accent is enough to remind us of his foreign beginnings without turning him into a vulgar stereotype. The overt hamminess of Bela Lugosi may be massively more fun, but Atwill wins out in the stakes of genuine scariness. And Atwill's success here has much to do with the kind of horror it is he appears in. As we see in Psycho or Silence of the Lambs, a cruel and unusual human mind is a far more frightening prospect than a mere monster.

The other great player here is Glenda Farrell, giving an engaging and likable spin on the wise-cracking go-getting heroine, a character of a sort she would later reprise in the Torchy Blane serial. She may get third billing, just under the better-known Fay Wray, but Farrell is the true lead of this horror-drama, and this in itself is part of the beguiling oddness of Mystery of the Wax Museum. Wray is the then-obligatory female victim, but from the gaggle of male good-guys no-one emerges as her heroic saviour. In a refreshing twist it is this smart sassy woman who takes on the eponymous mystery. The strong conventions of the day around women and action may mean Farrell is excused from the final rescue sequence, but the cunning and determination of her character mean we can view her as a forerunner of Ellen Ripley and Clarice Starling.

- Steffi_P

- 23 sept 2010

- Enlace permanente

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y añadir a tu lista para recibir recomendaciones personalizadas

Detalles

- Duración1 hora 17 minutos

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.37 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugerir un cambio o añadir el contenido que falta

Principal laguna de datos

By what name was Los crímenes del museo (1933) officially released in India in English?

Responde