Act of Violence is a 1949 American film noir directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Van Heflin, Robert Ryan, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor and Phyllis Thaxter.[3] It was produced by Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Adapted for the screen by Robert L. Richards from a story by Collier Young, the film confronts the ethics of war and was one of the first to address the problems of World War II veterans.[4]

| Act of Violence | |

|---|---|

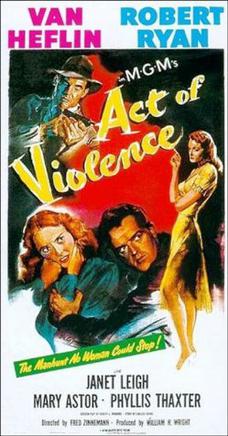

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Fred Zinnemann |

| Screenplay by | Robert L. Richards |

| Story by | Collier Young |

| Produced by | William H. Wright |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Surtees |

| Edited by | Conrad A. Nervig |

| Music by | Bronislau Kaper |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc.[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,290,000[2] |

| Box office | $1,129,000[2] |

Plot

editAfter surviving a Nazi POW camp where comrades were murdered by guards during an escape attempt, Frank Enley is respected for his fine character and good works in the small California town of Santa Lisa, where he, his young wife Edith and baby had settled after moving from the East. What his wife does not know is that Frank moved them in an attempt to escape the fall-out from events in that WWII prison camp.

Frank has a nemesis, Joe Parkson, once his best friend, who lived through the ordeal and was left with a crippled leg. Unable to convince Joe not to make an escape attempt, Frank had alerted the SS Nazi camp commander to the prisoners' plan, taking the camp commandant at his word that he would "go easy" on the men. The prisoners were bayonetted and left to die, and only Joe survived by playing dead. Joe is now determined to exact justice on Frank, whose location he has learned from a newspaper story commending Enley for his civic endeavors.

Joe's girlfriend, Ann Sturgess, knows everything about her man, but cannot dissuade him from his passion to right past wrongs by seeing Frank dead. Joe confronts Edith at their house and tells her the truth about Frank.

Doggedly pursued by Joe, Frank goes to a trade convention at a Los Angeles hotel. Edith shows up to hear the truth straight from her husband, before fleeing back home. Joe finds Frank and they scuffle. Frank runs through downtown Los Angeles and ends up on Skid Row, where he is picked up in a bar by a woman, Pat, who introduces him to a shady lawyer, Gavery, and a thug for hire, Johnny. A drunken Frank gives Johnny the information he needs to lure Joe into an ambush at the Santa Lisa train station.

Waking from his drunken binge, Frank regrets the deal. He goes home and tries to persuade Edith that it is all over. While she is seeing to their child, he leaves and goes to the station to warn Joe. Johnny is waiting with a gun, but as he fires, Frank jumps in front of Joe and is hit. Frank manages to grab Johnny as he speeds off in his car, causing it to crash into a lamppost, killing Johnny. Frank falls into the street near the fiery crash and dies. Joe, realizing what Frank has done, kneels by his old captain and tells the surrounding crowd that he will be the one to tell Frank's wife about her husband's death.

Cast

edit- Van Heflin as Frank R. Enley

- Robert Ryan as Joe Parkson

- Janet Leigh as Edith Enley

- Mary Astor as Pat

- Phyllis Thaxter as Ann Sturgess

- Berry Kroeger as Johnny

- Taylor Holmes as Gavery

- Harry Antrim as Fred Finney

- Connie Gilchrist as Martha Finney

- Will Wright as Pop

Production

editPrincipal photography on Act of Violence took place from May 17 to mid-July 1948, with added scenes shot in late August 1948. Location shooting included scenes at Big Bear Lake and the San Bernardino National Forest, California, accompanied by filming at the MGM Studios in Culver City. Some of the nighttime city scenes were shot in the slum neighborhoods of Los Angeles.[5]

Originally adapted from unpublished story by Collier Young, before he embarked on a career as an independent producer with his future wife Ida Lupino, the film was intended to be a small, independent film. Howard Duff was to be the star, but when MGM picked up the rights, Gregory Peck was to be paired with Humphrey Bogart in the leading roles. Robert Ryan was lent to MGM by RKO Pictures for the production.[6] Act of Violence was the third film made by Ryan in 1948, following Berlin Express and Return of the Badmen.[7]

Director Fred Zinnemann said that Act of Violence was the first film in which he felt he had full control of all the aspects of film-making.[8]

Reception

editAccording to MGM records, Act of Violence earned $703,000 in the US and Canada and $426,000 overseas, resulting in a loss of $637,000.[2]

Critical response

editBosley Crowther, reviewing the film for The New York Times, emphasized that it was a director's "tour de force. For this latter asset of the picture, we have Mr. Zinnemann to thank. He has pictured, at least, a visual setting for terror and violence and he has kept the pursued and the pursuer going at a grueling pace. In the former role, Van Heflin strains and sweats impressively. As his relentless pursuer, Robert Ryan is infernally taut. Mr. Zinnemann has also extracted a tortured performance from Janet Leigh as the fearful, confused and disillusioned wife of the hunted man and he has got squalid portraits of scoundrels from Mary Astor, Berry Kroeger and Taylor Holmes."[9]

Variety gave Act of Violence a positive review, writing "The grim melodrama implied by its title is fully displayed in Act of Violence...tellingly produced and played to develop tight excitement...The playing and direction catch plot aims and the characterizations are all topflight thesping. Heflin and Ryan deliver punchy performances that give substance to the menacing terror...It's grim business, unrelieved by lightness, and the players belt over their assignments under Zinnemann's knowing direction. Janet Leigh points up her role as Heflin's worried but courageous wife, while Phyllis Thaxter does well by a smaller part as Ryan's girl. A standout is the brassy, blowzy femme created by Mary Astor—a woman of the streets who gives Heflin shelter during his wild flight from fate."[10]

Film reviewer Roger Westcombe, writing for the Big House Film Society, considers Act of Violence unsettling, and wrote "Act of Violence...with a profundity, through its unsettling moral continuum, redolent not of Hollywood simplicities of good/evil but of the art one associates with Zinnemann's European background. This contains a clue. Fred and his brother escaped their native Austria in 1938, but their parents, waiting for U.S. visas that never came, perished—separately—in concentration camps. The 'survivor guilt' this awful closing engendered must resemble the emotional see-saw ride which fiction like the ethical pendulum of Act of Violence can only start to expiate."[11]

Currently, it holds a 90% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 10 reviews.[12]

Awards and honors

editFred Zinnemann was nominated for the Grand Prize of the Festival at the 1949 Cannes Film Festival for his work on Act of Violence.[13]

References

edit- ^ Act of Violence at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b c "The Eddie Mannix Ledger." Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study (Los Angeles).

- ^ Silver, Alain (2010). Film Noir: The Encyclopedia. Overlook Duckworth. p. 25. ISBN 978-0715638804.

- ^ "Film review: 'Act of Violence'." Harrison's Reports, December 25, 1948, p. 206.

- ^ "Original print information: 'Act of Violence'." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: September 17, 2022.

- ^ Stafford, Jeff. "Articles: 'Act of Violence'." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: September 17, 2022.

- ^ Jarlett 1997, p. 32.

- ^ Muller, Eddie (January 27, 2019) Intro to the Turner Classic Movies showing of Act of Violence

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. "Movie review: 'Act of Violence,' a Metro film with Van Heflin, Janet Leigh, new feature at Criterion.: The New York Times, January 24, 1949. Retrieved: May 7, 2016.

- ^ "Film review: 'Act of Violence'." Variety. December 21, 1948, p. 6. Retrieved: September 17, 2022.

- ^ Westcombe, Roger. "Film review: 'Act of Violence'." Big House Film Society,'2008. Retrieved: May 7, 2016.

- ^ Act of Violence at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: 'Act of Violence'." Archived October 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine festival-cannes.com. Retrieved: May 7, 2016.

Further reading

edit- Jarlett, Franklin (1997) Robert Ryan: A Biography and Critical Filmography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-0476-6.