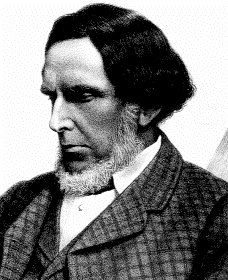

Robert Forester Mushet (8 April 1811 – 29 January 1891) was a British metallurgist and businessman, born on 8 April 1811, in Coleford, in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, England. He was the youngest son of Scottish parents, Agnes Wilson and David Mushet; an ironmaster, formerly of the Clyde, Alfreton and Whitecliff Ironworks.[1]

Robert Forester Mushet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 April 1811 Coleford, Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 29 January 1891 (aged 79) Cheltenham, England |

| Occupation | Metallurgist |

| Known for | Developing an inexpensive way to make high quality steel, by perfecting[clarification needed] the Bessemer Process Inventing the first commercially produced steel alloy. |

In 1818/1819, David Mushet built a foundry named Darkhill Ironworks in the Forest of Dean. Robert spent his formative years studying metallurgy with his father and took over the management of Darkhill in 1845.[2] In 1848, he moved to the newly constructed Forest Steel Works on the edge of the Darkhill site where he carried out over ten thousand experiments in ten years[3] before moving to the Titanic Steelworks in 1862.

It seems that[vague] Mushet only began using his middle name 'Forester' in 1845, and only occasionally at first. In his later years he said he had been given the name from the Forest of Dean, although he variously spelled it both 'Forester' and 'Forrester'.[4]

In 1876, he was awarded the Bessemer Gold Medal by the Iron and Steel Institute, their highest award.[5]

Robert Mushet died on 29 January 1891 in Cheltenham. He is buried with his wife and daughter, Mary, in Cheltenham Cemetery.

High quality steel

editIn the summer of 1848, Henry Burgess, editor of The Bankers' Circular, brought to Mushet a lump of white crystallised metal which he said was found in Rhenish Prussia.

... "Being familiar with alloys of iron and manganese," says Mr. Mushet, "I at once recognized this lump of metal as an alloy of these two metals and, as such, of great value in the making of steel. Later, I found that the white metallic alloy was the product of steel ore, called also spathose iron ore, being, in fact, a double carbonate of iron and manganese found in the Rhenish mountains, and that it was most carefully selected and smelted in small blast furnaces, charcoal fuel alone being employed and the only flux used being lime. The metal was run from the furnace into shallow iron troughs similar to the old refiners' boxes, and the cakes thus formed, when cold and broken up, showed large and beautifully bright facets and crystals specked with minute spots of uncombined carbon. It was called, from its brightness, 'spiegel glanz' or spiegel eisen, i.e., looking-glass iron. Practically its analysis was: Iron, 86…25; manganese, 8…50; and carbon, 5…25; making a total of 100…00."[6]

Mushet carried out many experiments with the metal, discovering that a small amount added during the manufacture of steel rendered it more workable when heated. It was not until 1856, however, that he realised the true potential of this property when his friend Thomas Brown brought him a piece of steel, made using the Bessemer Process, asking if he could improve its poor quality. Mushet carried out experiments on the sample, based on those he had previously carried out with spiegeleisen.

Henry Bessemer himself had realised that the problem of quality was due to impurities in the iron and concluded that the solution lay in knowing when to turn off the flow of air in his process; so that the impurities had been burned off, but just the right quantity of carbon remained. Despite spending tens of thousands of pounds on experiments, however, he could not find the answer.[7]

Mushet's solution was simple, but elegant; he first burnt off, as far as possible, all the impurities and carbon, then reintroduced carbon and manganese by adding an exact amount of spiegeleisen. This had the effect of improving the quality of the finished product, increasing its malleability – its ability to withstand rolling and forging at high temperatures.[1][8]

I saw then that the Bessemer process was perfected and that, with fair play, untold wealth would reward Mr. Bessemer and myself..."[citation needed]

Mushet's dream was never to be fulfilled. While others made fortunes from his discoveries, he failed to capitalise on his successes and by 1866 was destitute and in ill health. In that year his 16-year-old daughter, Mary, travelled to London alone, to confront Bessemer at his offices, arguing that his success was based on the results of her father's work.[9]

Bessemer, whose own process for producing steel was not economically viable without Mushet's method for improving quality, decided to pay Mushet an annual pension of £300, a very considerable sum, which he paid for over 20 years; possibly with a view to keeping the Mushets from legal action.[9]

Steel rails

editIn 1857, Mushet was the first to make durable rails of steel rather than cast iron, providing the basis for the development of rail transportation throughout the world in the late 19th century. The first of Mushet's steel rails was sent to Derby Midland railway station, where it was laid at a heavily used part of the station approach where the iron rails had to be renewed at least every six months, and occasionally every three. Six years later, in 1863, the rail seemed as perfect as ever, although some 700 trains had passed over it daily.[10] During its 16 years "life" 1,252,000 detached engines and tenders at the least, apart from trains, had passed over that rail.

Dozzles

editWhen steel solidifies in a mould, uneven cooling causes a central cavity or 'pipe' to form in the casting. In 1861, Mushet invented the 'Dozzle'; a clay cone or sleeve, heated white hot and inserted into the top of the ingot mould near the end of the pour, and then filled with molten steel. Its purpose was to maintain a reservoir of molten steel, which drained down and filled the pipe as the casting cooled. Mushet claimed this, and other small inventions of his, saved the steelmakers of Sheffield 'many millions of pounds' (in 19th century money), yet he received neither payment nor recognition for these inventions.[11] Dozzles, now called hot tops or feeder heads, are still in use today.

Steel alloys

editIn a second key advance in metallurgy Mushet invented 'R Mushet's Special Steel' (RMS) in 1868.[12][13] It was both the first true tool steel and the first air-hardening steel.[14] Previously, the only way to make steel hard enough for machine tools had been to quench it, by rapid cooling in water. With self-hardening (or tungsten) steel, machine tools could run much faster and were able to cut harder metals than had been possible previously. RMS revolutionised the design of machine tools and the progress of industrial metalworking, and was the forerunner of high speed steel.[13]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Anstis p. 85.

- ^ Anstis p. 157

- ^ Anstis pp. 175–176.

- ^ Webb p. 14.

- ^ "SHEFFIELD'S LIFE STORIES". Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Anstis p. 147.

- ^ Anstis p. 140.

- ^ a b Sir Henry Bessemer, F.R.S. An Autobiography, "Chapter 18 Manganese in Steel Making". Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Rolt, L.T.C (1974). Victorian Engineering. London: Pelican. p. 183.

- ^ Webb p. 15.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Sheffield Steel and America: A Century of Commercial and Technological Independence By Geoffrey Tweedale -- Cambridge University Press 1987 Page 66--68

- ^ Stoughton 1908, pp. 408–409,

Bibliography

edit- Anstis, Ralph (1997). Man of iron – man of steel: the lives of David and Robert Mushet. Albion House. ISBN 0-9511371-4-X.

- Stoughton, Bradley (1908). The Metallurgy of Iron and Steel (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Webb, Keith (2001). Robert Mushet and the Darkhill Ironworks. Black Dwarf. ISBN 1-903599-02-4.

Further reading

edit- Fred M. Osborn, The Story of the Mushets, London, Thomas Nelson & Sons (1952)