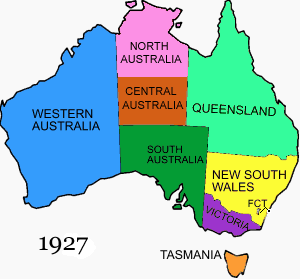

Central Australia was a territory of Australia that existed from 1927 to 1931. It was formed from the split of the Northern Territory in 1927 alongside the territory of North Australia, the dividing line between the two being the 20th parallel south. The two territories were merged in 1931 to reform the Northern Territory. The seat of government of the territory was Stuart, a town that was commonly known as "Alice Springs" and would be officially renamed so in 1933.

| Central Australia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory of Australia | |||||||||

| 1927–1931 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

A map of Australia from 1927 to 1931, with Central Australia in the centre | |||||||||

| Capital | Stuart (now Alice Springs) | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| • Coordinates | 23°42′0″S 133°52′12″E / 23.70000°S 133.87000°E | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Directly administered federal territory | ||||||||

| Responsible minister[a] | |||||||||

• 1927 | William Glasgow | ||||||||

• 1927–1928 | Charles Marr | ||||||||

• 1928 | Neville Howse | ||||||||

• 1928–1929 | Aubrey Abbott | ||||||||

• 1929–1931 | Arthur Blakeley | ||||||||

| Government Resident | |||||||||

• 1927–1929 | John C. Cawood | ||||||||

• 1929–1931 | Victor Carrington | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1 March 1927 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 11 June 1931 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

In the decades since Federation, white settlement of the Northern Territory was felt to be lacklustre due to Commonwealth inefficiency and indifference. George Pearce, the interior minister, proposed the North Australia Commission to handle development of all of Australia north of 20 degrees. This Commission would make decisions locally rather than rely on the Commonwealth government. The states of Queensland and Western Australia, which also had territory north of 20 degrees, were excluded from the final proposals on the Commission, meaning that it would in practice only focus on the northern part of the Northern Territory.

A bill to create the Commission, introduced in 1926, passed as the Northern Australia Act 1926. This act, taking effect on 1 March 1927, concentrated the efforts of the Commission by splitting the Northern Territory by the 20th parallel. The territory of Central Australia was created as an incidental part of this division, and unlike North Australia was not subject to the Commission. Both territories were administered by a Government Resident appointed by the federal government, who was assisted by a half-elected Advisory Council of four people. Ordinances of the Northern Territory continued in the new territories, which maintained a common non-voting representative to the Australian House of Representatives. The area remained sparsely inhabited, with little development and a poorly-specialised judiciary. During its brief existence, Central Australia was the site of the Coniston massacre, the last sanctioned killing of aborigines in Australian history.

The Commission aided the development of North Australia to a fair degree, but was seen by critics as an extravagance and interested in the pastoral industry over local whites. The Great Depression starting in late 1929 increased opposition to the body, which was abolished by legislation in 1930. This act, which returned development of the Northern Territory to the federal government and reformed it as a territorial entity, took effect in 1931, ending the separate existences of North Australia and Central Australia in the process.

History

editBackground

editPrior to Federation, what became the Northern Territory was administered by South Australia. Land was held by whites as leases from the government rather than in fee simple. Even after Federation, and the transfer of the territory and leasing power to Commonwealth hands, the conditions of leases granted by South Australia continued to apply in many cases. By 1922, Commonwealth management of the area, combined with the complexities introduced by lingering South Australian law, was felt to provide an unsatisfactory basis for the development of its rural industries. Furthermore, Commonwealth governments often changed, and none had a specific department dedicated to administering the sparsely-populated territory.[1]

In 1922, Horace Trower, who had been the Director of Lands for the territory, proposed a new unified policy to interior minister George Pearce to induce leaseholders to update their leases and ultimately spur the territory's development. Pearce, who had also been the Minister for Defence, was also concerned with the underpopulated North being a target for foreign invasion and agreed to Trower's ideas. Pearce's new policy, proposed in 1923, divided the territory into four districts; it also entitled the government to take 25 per cent of each lease's land in 1935 and another 25 per cent in 1945. This latter provision, another part of Pearce's program to populate the area, was unpopular with leaseholders who resisted such takings. On the opposite end of the spectrum, local parliamentarian Harold Nelson objected to its hindrance of Commonwealth control of lands. This controversy led to the provisions' being delayed to 1924; as finally enacted, they removed control of leasing from the local Administrator and placed it directly in the hands of the interior minister. Despite an ultimatum to leaseholders to update their leases within three years, almost a third of them had not done so by 1936.[1]

Pearce went further in his policies, proposing in November 1923 a Darwin-based commission to manage all of Australia north of the 20th parallel south – including portions of the states of Queensland and Western Australia. The Commonwealth government, as well as those of Queensland and Western Australia, would maintain control of the commission and be responsible for its costs; Pearce also intended to recruit the United Kingdom for help in its development, reasoning that the territory would serve well to accommodate the surplus population and economic growth of the British Empire. Cabinet accepted the proposal with significant modifications – Queensland and Western Australia would be omitted from the commission's remit with the possibility of their future joining, while a report on the state of the territory's development would be developed by George Buchanan, who had done similar work in South Africa, despite Pearce's preference of forming the commission before doing any reports.[1]

Buchanan's report criticised the inefficient administration of the territory by the Commonwealth, and recommended either that a board responsible to the interior minister be created for developing it, or the area become a de facto crown colony with the Administrator heading an independent budget subsidised with loans. Choosing the former, the government introduced the Northern Australia Commission Bill in February 1926 to create the commission; the Bill, intending to rectify the neglect and disorganisation of the previous two decades of Commonwealth policy on the territory, divided it into two regions by the 20th parallel, with separate Government Residents and administrations. The eponymous commission created by the act was to operate within the territory north of the 20th parallel, preparing plans for infrastructure and making recommendations to Parliament.[1] The Bill was passed as the Northern Australia Act, which took effect on 1 March 1927.[2]

Coniston massacre

editThe territory was considered the "last frontier" of Australian settlement, where sympathetic whites hoped that Aborigine traditions would continue to be practised;[3] indeed, well into the 1930s aborigines outnumbered whites within the territory and the area surrounding Stuart.[citation needed] Conflicts arose due to the resource scarcity and the fragility of the cattle industry, however, and the area was rife with indigenous "bush bandits" who speared cattle for food for want of employment by ranchers. This was exacerbated by a drought between 1925 and 1929 that led to the deaths of 85 per cent of the children at the Hermannsburg mission in the territory. In the meantime, white attitudes towards aborigines were paternalistic, torn between the desire to help them in times of hunger and the fear of "pauperizing" them and reducing their incentives to work.[3] In the 1928 Coniston massacre, punitive expeditions were carried out by white colonists led by Northern Territory Police constable William George Murray in response to the murder of a dingo hunter, resulting in the deaths of dozens to hundreds of people of the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye groups.[4]

Abolition

editThe North Australia Commission cost £27,500[b] a year to function; devoted largely to the interests of the pastoral industry, it lacked legitimacy in the eyes of the wider public, and was the target of criticism from leaseholders as an extravagance. The Great Depression starting from 1929 all but sealed the Commission's, and by extension the territories', fates.[1]

The Northern Territory Pastoral Lessees' Association submitted recommendations to Home Affairs Minister Arthur Blakeley on 28 March 1930 on how to develop the land of the territory.[5] The Association stated that the development of the Northern Territory had cost Australians up to £10 million[c] to develop at a loss, and among other things were adamant that the distinction between the territories be abolished.[5] Blakeley reacted favourably to the proposals and submitted them to Cabinet the next week.[5]

The Government tabled the Northern Territory (Administration) Bill 1930, which would merge the two territories back into one and abolish the North Australia Commission that had been established to supervise North Australia. Blakeley asserted that such a move would potentially save Australians £8,000-£9,000 per annum, but representative Nelson claimed that the abolition of the Commission and the reversion to Canberra administration over the Northern Territory would negatively impact progress in the area.[6]

The territory was disestablished effective 11 June 1931.[7]

Government

editWhereas the Northern Territory had been governed by an Administrator, both North Australia and Central Australia were governed by Government Residents.[8] The Government Resident of Central Australia was paid £750[d] annually while the Resident of North Australia received £900.[e][9] The seat of government for Central Australia was located at Stuart, which was commonly known as "Alice Springs" and would be officially renamed so in 1933; indeed, the Northern Australia Act 1926 itself dictated that the territory's seat be in "Alice Springs".[10]

The Government Resident of Central Australia was required to have a medical background.[8] He was instructed in his duties by the Minister of Home and Territories and assisted by an Advisory Council comprising two appointed and two elected members, the latter of whom were elected at large from the territory under the same franchise as the federal House of Representatives.[11] Ordinances of the Northern Territory continued to have effect in Central Australia, but could be amended or repealed by the Advisory Council.[12] The Advisory Council was not empowered to make ordinances regarding crown lands.[13] John C. Cawood was appointed as Government Resident as early as 15 December 1926 and served before resigning in November 1929, while Victor Carrington served from 11 December 1929 onwards; after the territories were re-merged, Carrington continued to serve as Assistant Administrator at Alice Springs until 1942.[14]

Unlike North Australia, which was placed under the remit of the Commission, development of Central Australia remained under the responsible Minister in the Commonwealth government.[8] North Australia and Central Australia both continued to be part of the Division of Northern Territory in the federal House of Representatives, whose member could participate in debates and join committees but could not vote and did not count in forming a government. For the entirety of the two territories' existence the representative for the division was Harold George Nelson.

The Supreme Court of the Northern Territory was nominally split into the Supreme Court of North Australia and the Supreme Court of Central Australia.[15] In practice, there was no developed judiciary in the territory, all judges being locally-appointed justices of the peace. A courthouse was built in Stuart and it was intended that a federal judge would visit it periodically to hear major cases. No such visits had occurred by 1930, however, and Central Australia's Supreme Court remained in Darwin in North Australia. This led to allegations of abuses within the judiciary, as witnesses were unwilling to travel that far. Crimes that fell out of the remit of the justices of the peace were reduced in the courts so that they could be heard by them; in one case a charge of murder was reduced to assault. Some action was taken by the federal government to correct these abuses.[16]

Economy

editWood grown in the area fetched a high price in markets in South Australia.[17] The development in the area was said by a tourist to be scarcely different from when "James [sic] Stuart" had first trekked across the area in 1862,[17] although it was expected that the automobile and railway would help spur development.[17] Cattle was also an important part of the economy, but was wracked by drought and relied on plentiful land and cheap aboriginal labour; indeed, the industry was so precarious that it could not even use the entire aborigine labour force. Aborigines were paid in food rather than in money; the industry was expected but not required to also pay labourers' kin.[3]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ 1927–1928: Minister for Home and Territories

1928–1931: Minister for Home Affairs - ^ $3,860,000 in 2010

- ^ $1,410,000,000 in 2010

- ^ $103,000 in 2010

- ^ $124,000 in 2010

References

edit- ^ a b c d e "George Pearce and Development of the North, 1921–37". Commonwealth Government Records about the Northern Territory. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020 – via National Archives of Australia.

- ^ "PROCLAMATION". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 19. Australia. 24 February 1927. p. 374. Retrieved 14 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c O'Brien, Anne (2015). "Hunger and the humanitarian frontier". Aboriginal History. 39. Aboriginal History Inc. ANU Press. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Bradley, Michael (2019). Coniston. Perth: UWA Press. ISBN 9781760801045.

- ^ a b c "NORTHERN TERRITORY". The Age. No. 23, 391. Victoria, Australia. 28 March 1930. p. 18. Retrieved 16 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Northern Territory (Administration) Bill: Second Reading". House of Representatives Hansard. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "PROCLAMATION". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 46. Australia. 11 June 1931. p. 931. Retrieved 15 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "Northern area of Australia to be divided". Santa Ana Register. Vol. 22, no. 46. Santa Ana, California. 21 January 1927. p. 21. Retrieved 14 August 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "RESIDENT GOVERNORS". Cairns Post (Qld. : 1909–1954). Qld.: National Library of Australia. 20 August 1926. p. 5. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Northern Australia Act 1926, §51

- ^ Northern Australia Act 1926, §§48–49

- ^ Northern Australia Act 1926, §38

- ^ Northern Australia Act 1926, §49

- ^ "(untitled)" (PDF). Northern Territory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2011.

- ^ Northern Australia Act 1926, §40

- ^ "CENTRAL AUSTRALIA". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 28, 764. New South Wales, Australia. 14 March 1930. p. 12. Retrieved 16 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "CENTRAL AUSTRALIA". The Age. No. 22, 584. Victoria, Australia. 24 August 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 16 August 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

Works cited

edit- An Act to make further provision for the Development and Government of the Northern Territory of Australia and for other purposes (16). Parliament of Australia. 1926.