Usipetes

The Usipetes or Usipii (in Plutarch's Greek, Ousipai,[1] and possibly the same as the Ouispoi of Ptolemy[2]) were an ancient tribe who moved into the area on the right bank (the northern or eastern bank) of the lower Rhine in the first century BC, putting them in contact with Gaul and the Roman empire. They are known first from the surviving works of ancient authors such as Julius Caesar and Tacitus. They appear to have moved position several times before disappearing from the historical record.

Name

[edit]While the Usipetes and their neighbours were referred to by the Romans as Germanic rather than Gauls, their name is normally explained as Celtic, as is also the case for many of their neighbours.

Following Rudolf Much, Usipetes has been traditionally interpreted as a Gaulish name meaning 'good riders'. The suffix -ipetes (*epetes) was proposed to be a Celtic cognate of the Latin equites. Proponents of the theory pointed out to the fact that Caesar and others reported them to have strong cavalry.[3] However, this etymology has been rejected as linguistically untenable in more recent scholarship.[4]

Stefan Zimmer has proposed in 2006 to reconstruct the name as the Gaulish *Uχsi-pit-s (plural *Uχsi-pit-es), formed with the Indo-European stem *upsi- ('on-high' or 'above'; cf. Gaul. *ouχsi > uχe 'high') attached to *k̑u̯ei̯t- ('to appear'; with the P-Celtic sound shift kʷ- > p-). He thus suggests to translate Usipetes (*Uχsipites) as 'shining in the heights', or 'radiant', which he explains as a typical boastful tribal name.[4]

History

[edit]Gallic wars

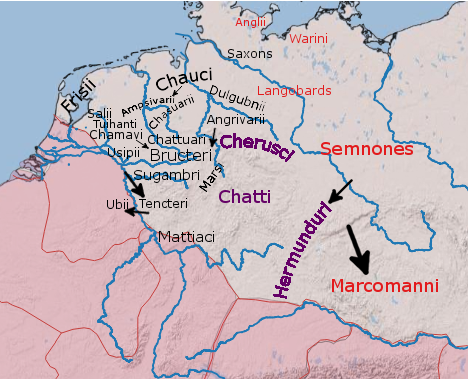

[edit]In his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Caesar describes how two tribes, the Tencteri and Usipetes, had been driven from their traditional lands by the Germanic Suebi, whose military dominance had led to constant warfare and neglect of agriculture. This original homeland of the two tribes is not clear but by the time of Caesar the Suebi had settled in a very large wooded area to the east of the Ubii, who at this time lived on the east bank of the Rhine, on the opposite bank from where Cologne is today. It has been argued that the Tencteri and Usipetes specifically may have come from the area of the Weser river to the east of the Sigambri, because it is near to where the two tribes appeared on the Rhine, and Caesar reports the Suevi in this area. It would also explain the apparently friendly relations of the Tencteri and Usipetes with the Sigambri, who might have been their traditional neighbours.[5] (In later Roman times this area inhabited by Caesar's Suebi was inhabited by the Chatti.[6])

In the winter 55 BC, having failed to find new lands elsewhere in Germania, they came to the Rhine, into the territory of the Menapii, a Belgic tribe who had land on both sides of the river, and had not yet submitted to Roman rule. Alarmed by the scale of the incursion, the Menapii had withdrawn from their territories east of the Rhine and successfully resisted the Germani bid to cross it for some time. The Germani feigned a retreat, allowing the Menapii to return to their territories east of the Rhine. Their cavalry then returned and made a surprise night attack. They crossed the river and seized Menapian boats, occupied Menapian villages and towns, and spent the rest of the winter living on Menapian provisions.

Concerning the exact location of this slaughter, there has long been some doubt. Caesar describes a confluence of the Rhine and Maas rivers, but there is no such confluence. Archaeologist Nico Roymans has announced in 2015 that convincing evidence has been found that it was in fact in the confluence of Waal, a branch of the Rhine and not the Rhine itself, and the Maas/Meuse, near Kessel.[7] On the other hand, the third century historian Cassius Dio described the place as being in the country of the Treveri near the Moselle, which had the same name as the Maas in Latin (Mosa) and does enter the Rhine in that region.[8] This is however very far from the Menapii.

Caesar, fearing how the Gauls on the left bank might react, hurried to deal with this threat to his command of the region. He discovered that a number of Gaulish tribes had attempted to pay these Germani generously to leave, but the Tencteri and Usipetes had ranged further, coming to the frontiers of the Condrusi and Eburones, who were both under the protection of the Treveri to their south. Caesar convened a meeting of the Gaulish chiefs, and, pretending he did not know of their attempts at bribery, demanded cavalry and provisions for war against the Tencteri and Usipetes.

The Tencteri and Usipetes sent ambassadors to Caesar as he advanced. While they boasted of their military strength, claiming that they could defeat anyone but the Suebi, they offered an alliance, requesting that Caesar assign them land. Caesar refused any alliance so long as the Tencteri and Usipetes remained in Gaul. He proposed settling them in the territory of the Ubii, another Germanic tribe who had sought his help against the aggression of the Suebi, there being no land available in Gaul. (The Ubii were at this time on the east bank of the Rhine, but would later be settled on the left bank, where their capital became Cologne.)

The ambassadors requested a truce of three days, during which time neither side would advance towards the other, and they took Caesar's counter-proposal to their leaders for consideration. But Caesar would not accept this, believing the Germani were buying time for the return of their cavalry, who had crossed the Meuse to plunder the Ambivariti a few days previously. As Caesar continued to advance, further ambassadors requested a three-day truce for them to negotiate with the Ubii about his settlement proposal, but Caesar refused for the same reason. He offered a single day, during which he would advance no more than four miles, and ordered his officers to act defensively and not to provoke battle.

The Germanic cavalry, although outnumbered by Caesar's Gallic horsemen, made the first attack, forcing the Romans to retreat. Caesar describes a characteristic battle-tactic they used, whereby horsemen would leap down to their feet and stab enemy horses in the belly. Accusing them of violating the truce, Caesar refused to accept any more ambassadors, arresting some who came requesting a further truce, and led his full force against the Germanic camp. The Usipetes and Tencteri were thrown into disarray and forced to flee, pursued by Caesar's cavalry, to the confluence of the Rhine and Meuse. Many were killed attempting to cross the rivers.[9][10] They found refuge on the other side of the Rhine amongst the Sicambri (or Sugambri).

Plutarch reports that back in Rome,

Cato pronounced the opinion that they ought to deliver up Caesar to the Barbarians, thus purging away the violation of the truce in behalf of the city, and turning the curse therefor on the guilty man. Of those who had crossed the Rhine into Gaul four hundred thousand were cut to pieces, and the few who succeeded in making their way back were received by the Sugambri, a German nation. This action Caesar made a ground of complaint against the Sugambri, and besides, he coveted the fame of being the first man to cross the Rhine with an army.[11]

Later mentions

[edit]The Usipetes, or "Usipi" as they were named by most authors after Caesar, remained in the same region although the details are not clear.

- In 16 BC, the Tencteri, Usipetes and Sicambri once again crossed the Rhine and attacked Gaul. Marcus Lollius was defeated in the clades Lolliana and the Germanic tribes took the standard of the Legio V Macedonica.[12]

- In 12 BC and 11 BC at the time of Drusus, the Usipi are described as living between Nijmegen and the Sugambri, and neighboring the Tubantes, which means they were in the region of the present day Dutch-German border, north of the Rhine and Lippe rivers.[12]

- In 14 AD the Usipetes still lived north of the Lippe and joined the Bructeri and Tubantes when fighting Germanicus.

- In 17 AD, Strabo describes the Usipi as being among the defeated tribes displayed in the triumphal procession of Germanicus.

Tacitus also describes in his Annales how in 58 AD the Ampsivarii demanded to be allowed to use the reserved lands on Roman border at the Rhine which had recently belonged to the Usipii, but it is not clearly explained where or why the Usipii had moved.[13] What is mentioned is that when the Ampsivarii retreated from the Romans, and apparently also away from the lands of the Bructeri and Tencteri (who had already stood down), they moved towards the lands of the Tubantes and Usipii.[14] So the Usipi seem to have settled for some time after Caesar on the north of the Rhine, and then later moved further north, away from the Roman frontier, to become neighbours of the Tubantes.

Tacitus' Agricola (chapter 28), recounts how a cohort drafted into the Roman army mutinied whilst on campaign in northern Britain (presumably on the west coast) with his father-in-law, the general Gnaeus Julius Agricola (probably in AD 82, although the chronology is disputed). They killed the centurion and regular Roman soldiers based with them for training purposes, then stole three ships and sailed round the northern end of Britain, their hardships including being driven to cannibalism by shortage of food. They finally made landfall in the territory of the Suebi, where some were captured by that tribe. Others were caught by the Frisii and a few survivors were sold into slavery to tell their tale.[12][15]

Tacitus in his Germania describes them as now living in 98 AD between the Chatti and the Rhine, near the Tencteri. This apparently indicates a significant movement south from the area near the Tubantes.[16]

Later, the difficult to interpret description given in Claudius Ptolemy's Geography describes the "Ouispoi" (Uispi or Vispi) living south of the Tencteri, between the Rhine and the Abnoba mountains, but north of the Agri Decumates. If these are the Usipi, then they had moved considerably. (The same passage can also be interpreted as describing the Tencteri as having moved south.)[17]

In the Peutinger map, the area across from Cologne and Bonn is shown as inhabited by the "Burcturi" (Bructeri), who may have included a mixture of several of the original Germanic tribes from over the Rhine, including the Tencteri and Usipetes. The Bructeri had apparently therefore also moved south. To their north were Franks and to their south on the Rhine were Suevi, both of whom represent new forces in the area.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ As accusative Ousipas, Plut. Caes. 22.

- ^ Geography 2.10

- ^ Ludwig Rübekeil, Diachrone Studien zur Kontaktzone zwischen Kelten und Germanen, Wien, 2002, p. 81f.

- ^ a b Zimmer 2006.

- ^ Attema, P. A. J.; Bolhuis, E. (December 2010). Palaeohistoria 51/52 (2009/2010). ISBN 9789077922736.

- ^ Peck (1898), Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities

- ^ "'Genocidaire slachting' onder leiding van Julius Caesar bij Kessel - National Geographic Nederland/België". www.nationalgeographic.nl. Archived from the original on 2015-12-15.

- ^ Cassius Dio 39.47 English, Latin.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.1-15

- ^ Lee, K.H. "Caesar's Encounter with the Usipetes and the Tencteri." Greece & Rome 2nd vol. 2 (1969): 100-103.

- ^ Plut. Caes. 22

- ^ a b c Lanting; Van Der Plicht (2010), "De 14C chronologie van de Nederlandse Pre- and Protohistorie VI: Romeinse tijd en Meronvingische periode, deel A: historische bronnen en chronologische thema's", Palaeohistoria, 51/52, ISBN 9789077922736

- ^ Tac. Ann. 13.55

- ^ Tac. Ann. 13.56

- ^ Tacitus, Agricola 28

- ^ Tac. Ger. 32

- ^ Schütte, Ptolemy's Maps of Northern Europe, page 118

Bibliography

[edit]- Lee, K. H. (1969). "Caesar's Encounter with the Usipetes and the Tencteri". Greece & Rome. 16 (1): 100–103. doi:10.1017/S0017383500016417. ISSN 1477-4550.

- Zimmer, Stefan (2006), "Usipeten/Usipier und Tenkterer", Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 31 (2 ed.)