Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

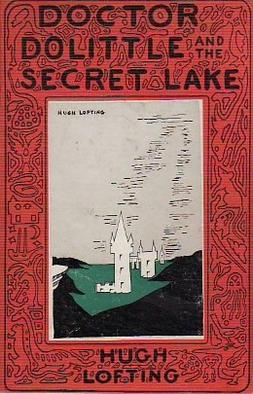

First edition | |

| Author | Hugh Lofting |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Hugh Lofting |

| Language | English |

| Series | Doctor Dolittle |

| Genre | Fantasy, children's novel |

| Publisher | J. B. Lippincott |

Publication date | 1948 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) |

| Preceded by | Doctor Dolittle's Return |

| Followed by | Doctor Dolittle and the Green Canary |

Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake is a Doctor Dolittle book written by Hugh Lofting. The book was published posthumously in 1948,[1] 15 years after its predecessor.[2] Fittingly, it is the longest book in the series, and the tone is the darkest; World War II took place before the book was published, during which Lofting had published his 1942 anti-war poem Victory for the Slain. The book contains passages that almost border on being misanthropic with some very powerful passages concerning war and Man's inhumanity to man.

Style

[edit]The book starts with the Doctor giving up his dream of lengthening human life with discoveries he made on the Moon, and showing signs of despair. The tone of the passages for the first time acknowledges 'nature red in tooth and claw': another of the Doctor's experiments, a house where scavengers and parasites can live without harming other creatures, is also doomed to failure.

The Doctor then receives an urgent call to rescue what is literally his oldest friend: Mudface the Giant Turtle, who was a passenger on Noah's Ark. Mudface's tale of the Great Flood is told, which was missing from Lofting's 1923 novel Doctor Dolittle's Post Office. Mudface's account of the Flood and its aftermath takes up most of the book, and it is by no means a jolly story. There are many references to genocide and slavery, including a passage where animals gather outside a hut to devour the humans inside (a young man and his beloved, who are the most sympathetic characters next to Mudface and his mate).

Comedy is reduced to a mere sprinkling, just enough to lighten some of the more dark passages. The book stands alone in style but with, arguably, some of Hugh Lofting's most powerful writing.

Also of note is that Lofting's depiction of African characters is far less caricatured than in previous novels.

References

[edit]- ^ Drew, Bernard A. (8 March 2010). Literary Afterlife: The Posthumous Continuations of 325 Authors' Fictional Characters. McFarland. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-7864-5721-2.

- ^ "Book Review". The Gazette and Daily. 21 January 1949. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

External links

[edit]- Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- 1948 British novels

- 1948 fantasy novels

- Doctor Dolittle books

- British children's novels

- Novels about Noah's Ark

- Novels published posthumously

- J. B. Lippincott & Co. books

- Novels set in Africa

- 1948 children's books

- Children's books based on the Bible

- Children's fantasy novel stubs

- 1940s children's novel stubs

- 1940s speculative fiction novel stubs