A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas

A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty's ship, the Endeavour is a 1773 book based on the papers of Sydney Parkinson, who accompanied Joseph Banks as botanical illustrator on the first voyage of James Cook. Parkinson died at sea in 1771 on the return voyage, and the Journal was compiled by William Kenrick for Parkinson's brother Stanfield, who quarrelled with Banks about his brother's papers and belongings and attacked Banks and others in the book's preface. A legal injunction prevented the publication of the Journal until after the official account of Cook's voyage, edited by John Hawkesworth, had appeared. A second edition appeared in 1784 with explanatory remarks by John Fothergill.

The book is organised chronologically and mainly describes the voyage from England to Tahiti, the time spent there, and the encounters with New Zealand and Australia. It contains Parkinson's vocabularies of several Pacific languages and also many plant names given by Daniel Solander, but most of these have not been accepted as botanical names. The book is illustrated by engravings based on Sydney Parkinson's drawings. It has been praised for its authenticity but criticised by botanists for the low quality of the botanical content.

Background and publication

[edit]

Sydney Parkinson was born in Edinburgh c. 1745 into a Quaker family and moved to London c. 1766, where Parkinson taught drawing and was introduced to Joseph Banks and worked for him on natural history drawings. When Joseph Banks joined James Cook on his first voyage, he took Parkinson with him as part of his entourage,[1] for a salary of £80 per year,[2] equivalent to £10,000 in 2023. Before embarking on the journey, Parkinson had made a will leaving all his belongings to his brother and sister.[3] While at sea, typically Banks and the botanist Daniel Solander worked together on the plant specimens collected on land excursions, with Parkinson drawing the plants, and Solander writing the descriptions and noting the plant name on the back side of Parkinson's drawings.[4][5]

Parkinson kept a journal of the voyage from the start until he fell ill in January 1771.[6] Unlike the ship's officers, Parkinson was not under orders to yield his journals to the Admiralty or to keep silent about details of the journey.[2] According to his shipmates, his journal was substantial and "much admired", but no continuous version or "fair copy" has ever been found.[6][7] On the return voyage, Parkinson fell ill with malaria and dysentery contracted at Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia),[8] together with most of his shipmates.[9] After his death on 26 January 1771, his employer Joseph Banks took care of his possessions.[8] Banks announced the death of Parkinson to his brother Stanfield Parkinson, an upholsterer, after the ship had returned to England.[10] Stanfield asserted that his brother's collections and journals and everything done in his spare time should be among the inheritance,[3] and that only the botanical artwork was included in Parkinson's contract with Banks.[11]

A lengthy dispute ensued, and when Banks was slow to hand over Sydney's property, Stanfield became increasingly suspicious of Banks, especially because he heard rumours that James Lee was to receive his brother's journal.[12] This was based on a misunderstanding between Banks and Daniel Solander, who later clarified that the dying Parkinson had just asked that James Lee should be allowed to read his papers.[13] The quarrel was finally mediated by John Fothergill, a Quaker physician and botanist who had known the Parkinson family in Edinburgh.[12] Fothergill approached Banks and proposed and later witnessed an agreement between Banks and Parkinson's siblings.[14] Banks paid £500 (equivalent to £80,000 in 2023) as outstanding salary and as compensation for the collections and papers,[3] a settlement that did not satisfy Stanfield.[7] Banks allowed him to borrow some of his brother's papers after Fothergill had made a strict promise that they would not be misused.[15] Despite this promise, Stanfield arranged for a copy to be made and decided to publish the journal, attempting to pre-empt the official publication of Cook's and Banks's journals, which was edited by the writer John Hawkesworth.[15] The writer William Kenrick was engaged as editor for Parkinson's papers, and added a preface attacking both Banks and Fothergill.[7][16] A legal injunction obtained by Hawkesworth prevented the publication until after the latter's book, An Account of the Voyages, had appeared in 1773.[11] These troubles played a part in the decline of Stanfield Parkinson's mental and physical health; he was committed to an insane asylum and died in 1776.[17][18] The publication of the preface had been against Quaker rules, but Stanfield was declared insane before he could be excluded from the Westminster meeting, the Quaker congregation where Fothergill was also a member.[19] Several of the engravings in Hawkesworth's book were based on Parkinson's drawings, but this was not acknowledged.[20] While Fothergill had asked for such an acknowledgment, Banks himself had written to Hawkesworth advising against it.[17]

The Journal appeared on 12 June 1773, two days after Hawkesworth's book.[21] Fothergill, angry about attacks on him made in the preface, responded at some point between 1773 and 1777 with the publication of Explanatory Remarks on the Preface to Sydney Parkinson's Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, denouncing Stanfield Parkinson's "treacherous behaviour". After the latter's death, Fothergill bought 400 remaining copies of the Journal from the family, and his Explanatory Remarks were added to the remaining copies.[17] After Fothergill's 1780 death, a second edition was published in 1784, edited by John Coakley Lettsom, another Quaker botanist.[17][20] This second edition contains some more additional material including maps showing all three of Cook's voyages and outlines of several recent voyages of exploration.[22]

Content

[edit]

The book is structured roughly chronologically and broken up in three main parts: the first describes the voyage from England to Tahiti and contains chapters about plants, language, and tools that Parkinson had observed in Tahiti. The second part is concerned mostly with New Zealand; the third with Australia, the voyage to Batavia and the languages encountered on this part of the journey. A very brief fourth part recounts the return voyage after Parkinson's death. It is not certain whether the comments in the Journal are all from Sydney Parkinson or whether his brother or Kenrick inserted their own ideas.[24] However, the work of Kenrick has been described as "quickly and competently done".[17] The linguistic knowledge displayed in the book was unprecedented in a voyage narrative.[25]

The journal contains some elements not found in other accounts of the voyage. For example, in the description of the near-fatal shipwreck when HMS Endeavour struck Endeavour Reef in June 1770 and all pumps had to be continuously manned, Parkinson notes that everyone, including even the captain, took part.[26]

The book contains 74 binomial names of Tahitian plant species together with their indigenous names. They are not arranged in any systematic order, and the names and descriptions were all given by Daniel Solander.[27] Seven of the generic names and 46 binomials were new, but most lack a precise botanical description and are not accepted names in botanical nomenclature.[28] The breadfruit appears as Sitodium, its description containing—in the words of botanist William T. Stearn—"just enough information to make its acceptance controversial". The competing name Artocarpus was described in 1775/76 by Georg Forster and Johann Reinhold Forster, the naturalists on the second voyage of James Cook, in their book Characteres generum plantarum.[29]

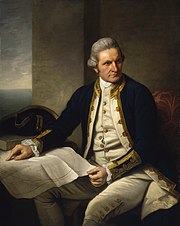

Besides a portrait of Parkinson, the book contains 27 engravings based on Parkinson's drawings, by various engravers.[2] In some copies of the 1784 edition, they were hand coloured.[22] Some may include alterations by the engraver; for example, Thomas Chambers's engraving Two of the Natives of New Holland, Advancing to Combat presents them with dart and sword, although Parkinson drew a woomera, a spear-throwing device. The holes in the shield are featured in Parkinson's descriptions, not in his known drawings.[31] The posture and stance of the warriors in the engraving are similar to heroic figures of classical antiquity, unlike those in any of Parkinson's drawings of indigenous peoples, and are likely due to Chambers.[32]

Reception and legacy

[edit]The reviewer of the 1784 second edition for The Gentleman's Magazine explained the controversy around the first edition and praised the book, noting the authenticity of its observations. The illustrations and the word lists are mentioned as giving the Journal a "superiority over those of contemporary voyagers, who ... have departed from the simplicity of Nature."[33]

In his edition of Cook's journals of the first voyage, the Cook scholar John Beaglehole describes the book as a "primary authority for the voyage".[6] Reviewing the 1984 reprint edition,[34] the maritime historian Barry M. Gough praises Parkinson and states "he would have produced a better book had he lived", and gives the same assessment as Beaglehole on the authority of the book.[35]

The botanist Elmer Drew Merrill, while calling the fact that the journal was published "on the whole, fortunate",[36] dismissed the quality of the botanical content, stating "It is clear that Parkinson ... did not realize what he was doing when he recorded the Solander generic and specific names, and his brother Stanfield ... was even less informed", and went on to suggest that the entire Journal be considered outlawed as an opus utique oppressum.[37] This suggestion was not followed by all authors.[38] Another botanist, Harold St. John, rejected the names in Parkinson's book because they contained hyphens, but accepted the same names without hyphens as validly published in a 1774 German translation by an author known as "Z" of the chapter on plants.[39] Other authors consider the question of hyphens to be just a typographical error.[38] The identity of "Z" was unknown until 2006, when he was identified as Friedrich August Zorn von Plobsheim (1711–1789).[40]

References

[edit]- ^ Rienits 2006.

- ^ a b c Holmes 1968, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Miller 1911, p. 125.

- ^ Beaglehole 1962, pp. 33–34, 36.

- ^ Gardiner 2001.

- ^ a b c Beaglehole 1968, p. ccliii.

- ^ a b c Joppien & Smith 1985, p. 53.

- ^ a b Allen 2004.

- ^ Beaglehole 1974, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Beaglehole 1962, p. 57.

- ^ a b Taylor 2018, p. 29.

- ^ a b Beaglehole 1962, p. 58.

- ^ Anderson 1954.

- ^ Beaglehole 1962, p. 59.

- ^ a b Beaglehole 1962, p. 60.

- ^ Beaglehole 1962, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e Joppien & Smith 1985, p. 54.

- ^ Lysaght 1981, p. 81.

- ^ Pointon 1997, pp. 418, 431.

- ^ a b Miller 1911, p. 126.

- ^ Beaglehole 1974, p. 459.

- ^ a b Holmes 1968, p. 53.

- ^ Joppien & Smith 1985, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Merwin 1991, p. 10.

- ^ Bil 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Nicandri 2020, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Merrill 1954, p. 328.

- ^ Merrill 1954, p. 329.

- ^ Stearn 1969, p. 75.

- ^ Joppien & Smith 1985, p. 221.

- ^ Joppien & Smith 1985, p. 45.

- ^ Joppien & Smith 1985, p. 48.

- ^ Anon 1785.

- ^ Parkinson 1984.

- ^ Gough 1987, p. 261.

- ^ Merrill 1954, p. 327.

- ^ Merrill 1954, p. 331.

- ^ a b Nicolson & Fosberg 2004, p. 54.

- ^ St. John 1972.

- ^ Pieper 2006.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, D.E. (23 September 2004). "Parkinson, Sydney". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21377.

- Anderson, A. W. (16 January 1954). "Sydney Parkinson". The Gardeners' Chronicle. 135. London: 24–25. OCLC 12835111.

- Anon (1785). "Impartial and Critical Review of New Publications". The Gentleman's Magazine. 55: 52.

- Beaglehole, John C. (1968) [1955]. The Journals of Captain James Cook: The Voyage of the Endeavour, 1768–1771. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press : Hakluyt Society. OCLC 223185477.

- Beaglehole, J. C (1962). The Endeavour journal of Joseph Banks 1768–1771. Sydney: Trustees of Public Library of N.S.W. in association with Angus and Robertson. OCLC 222980498.

- Beaglehole, J. C (1974). The life of Captain James Cook. London: Adam & Charles Black. OCLC 480115019.

- Bil, Geoff (22 December 2020). "Tangled compositions: Botany, agency, and authorship aboard HMS Endeavour". History of Science. 60 (2): 183–210. doi:10.1177/0073275320971109. ISSN 0073-2753. PMID 33349078. S2CID 229351442.

- Gardiner, Brian (July 2001). "Editorial" (PDF). The Linnean. 17 (3): 1–7.

- Gough, Barry M. (1987). "Review of A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas; Captain Cook's Second Voyage: The Journals of Lieutenants Elliott and Pickersgill; In the Wake of Cook: Exploration, Science & Empire, 1780–1801; Autobiographical Narrative of Residence and Exploration in Australia 1832–1839 by Edward John Eyre; Journals of the Central Australian Expedition, 1844-5". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 19 (2): 260–264. doi:10.2307/4050425. ISSN 0095-1390. JSTOR 4050425.

- Holmes, Maurice (1968). Captain James Cook; a bibliographical excursion. New York, B. Franklin.

- Joppien, Rüdiger; Smith, Bernard (1985). The Art of Captain Cook's Voyages. Vol. One. The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768–1771. New Haven and London: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03450-4. OCLC 12544694.

- Lysaght, Averil (1981). "A Letter from Sydney Parkinson in Batavia to Dr John Fothergill". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 36 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1981.0005. ISSN 0035-9149. JSTOR 531658. PMID 11610946. S2CID 30253081.

- Merrill, Elmer D. (1954). The botany of Cook's voyages and its unexpected significance in relation to anthropology, biogeography, and history. Chronica botanica. Vol. 14. Waltham, Mass.: Chronica Botanica Co.

- Merwin, W. S. (1991). "The Tree on One Tree Hill". Manoa. 3 (1): 1–19. ISSN 1045-7909. JSTOR 4228566.

- Miller, William F. (1911). "Sydney Parkinson and his Drawings". Journal of the Friends Historical Society. 8 (3): 123–127.

- Nicandri, David L. (2020). Captain Cook Rediscovered: Voyaging to the Icy Latitudes. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-6222-6.

- Nicolson, Dan H; Fosberg, F. Raymond (2004). The Forsters and the botany of the Second Cook Expedition (1772–1775). Ruggell, Liechtenstein; Königstein, Germany: A.R.G. Gantner Verlag ; Distributed by Koeltz Scientific Books. ISBN 978-3-906166-02-5. OCLC 55731186.

- Parkinson, Sydney (1984) [1784]. A journal of a voyage to the South Seas in His Majesty's ship the Endeavour. London: Caliban Books. OCLC 165711349.

- Pieper, Harald (2006). ""Z": The Breadfruit Author Identified". Willdenowia. 36 (1): 589–593. doi:10.3372/wi.36.36155. ISSN 0511-9618. JSTOR 3997733. S2CID 85738541.

- Pointon, Marcia (1997). "Quakerism and Visual Culture 1650–1800". Art History. 20 (3): 397–431. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.00069. ISSN 1467-8365.

- Rienits, Rex (2006) [1967]. "Parkinson, Sydney (1745–1771)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Stearn, William T. (1969). "A Royal Society Appointment with Venus in 1769: The Voyage of Cook and Banks in the 'Endeavour' in 1768–1771 and Its Botanical Results". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 24 (1): 64–90. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1969.0007. ISSN 0035-9149. JSTOR 530741. S2CID 143709486.

- St. John, Harold (December 1972). "The scientific names in the German edition of Parkinson's plants of use for food, medicine etc., in Otaheite". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 4 (4): 305–310. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1972.tb00697.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- Taylor, James (20 September 2018). Picturing the Pacific: Joseph Banks and the shipboard artists of Cook and Flinders. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-5544-9.