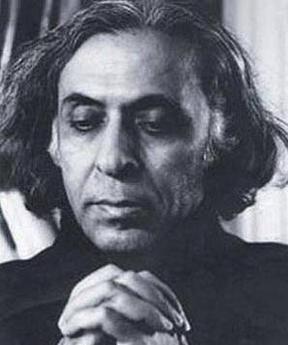

Raja Rao

Raja Rao | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 November 1908 Hassan, Kingdom of Mysore, British India (now in Karnataka, India) |

| Died | 8 July 2006 (aged 97) Austin, Texas, USA |

| Occupation | Writer, professor |

| Language | Kannada, French, English |

| Alma mater | Osmania University University of Madras, University of Montpellier Sorbonne |

| Period | 1938–1998 |

| Genre | Novel, short story, essay |

| Notable works | Kanthapura (1938) The Serpent and the Rope (1960) |

| Notable awards |

|

| Website | |

| therajaraoendowment | |

Raja Rao (8 November 1908 – 8 July 2006) was an Indian-American writer of English-language novels and short stories, whose works are deeply rooted in metaphysics. The Serpent and the Rope (1960), a semi-autobiographical novel recounting a search for spiritual truth in Europe and India, established him as one of the finest Indian prose stylists and won him the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1963.[1] For the entire body of his work, Rao was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1988. Rao's wide-ranging body of work, spanning a number of genres, is seen as a varied and significant contribution to Indian English literature, as well as World literature as a whole.[2]

Early life

[edit]Raja Rao was born on 8 November 1908 in Hassan, in the princely state of Mysore (now in Karnataka in South India) into a Kannada-speaking Brahmin family[3][4] and was the eldest of 9 siblings, with seven sisters and a brother named Yogeshwara Ananda. His father, H.V. Krishnaswamy, taught Kannada, the native language of Karnataka, and Mathematics at Nizam College in Hyderabad. His mother, Gauramma, was a homemaker who died when Raja Rao was 4 years old.[4]

The death of his mother when he was four left a lasting impression on the novelist – the absence of a mother and orphanhood are recurring themes in his work. Another influence from early life was his grandfather, with whom he lived in Hassan and Harihalli or Harohalli).[citation needed]

Rao was educated at a Muslim school, the Madarsa-e-Aliya in Hyderabad. After matriculation in 1927, he studied for his degree at Nizam's College. Osmania University, where he became friend with Ahmed Ali. He began learning French. After graduating from the University of Madras, having majored in English and history, he won the Asiatic Scholarship of the Government of Hydrabad in 1929, for studying abroad.[citation needed]

Rao moved to the University of Montpellier in France. He studied French language and literature, and later at the Sorbonne in Paris, he explored the Indian influence on Irish literature. He married Camille Mouly, who taught French at Montpellier, in 1931. The marriage lasted until 1939. Later he depicted the breakdown of their marriage in The Serpent and the Rope. Rao published his first stories in French and English. In 1931 to 1932, he contributed four articles written in Kannada for Jaya Karnataka, an influential journal.[5]

Nationalist novelist

[edit]Returning to India in 1939, he edited Changing India with Iqbal Singh, an anthology of modern Indian thought from Ram Mohan Roy to Jawaharlal Nehru. He participated in the Quit India Movement of 1942. In 1943–1944 he co-edited a journal from Bombay called Tomorrow with Ahmad Ali. He was a prime mover in the formation of cultural organisation Sri Vidya Samiti, devoted to reviving the values of ancient Indian civilisation. [citation needed]

Rao's involvement in the nationalist movement is reflected in his first two books. The novel Kanthapura (1938) was an account of the impact of Gandhi's teaching on nonviolent resistance against the British. Rao borrows the style and structure from Indian vernacular tales and folk-epics. He returned to the theme of Gandhism in the short story collection The Cow of the Barricades (1947). The Serpent and the Rope (1960) was written after a long silence, and dramatised the relationships between Indian and Western culture. The serpent in the title refers to illusion and the rope to reality.[6] Cat and Shakespeare (1965) was a metaphysical comedy that answered philosophical questions posed in the earlier novels. He had great respect for women, and once said, "Women is the Earth, air, ether, sound, women is the microcosm of the mind".[7]

Later years

[edit]Rao relocated to the United States and was Professor of Philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin from 1966 to 1986, when he retired as Emeritus Professor. Courses he taught included: Marxism to Gandhism; Mahayana Buddhism; Indian philosophy: The Upanishads; Indian philosophy: The Metaphysical Basis of the Male and Female Principle; and Razor's Edge.[8]

In 1965, he married Katherine Jones, an American stage actress. They had one son, Christopher Rama. In 1986, after his divorce from Katherine, Rao married his third wife, Susan Vaught, whom he met when she was a student at the University of Texas in the 1970s. In 1988 he received the prestigious International Neustadt Prize for Literature. In 1998 he published Gandhi's biography Great Indian Way: A Life of Mahatma Gandhi.

Rao died of heart failure on 8 July 2006, at his home in Austin, Texas, at the age of 97.[9][10][4]

Raja Rao Award for Literature

[edit]The 'Raja Rao Award for Literature' was created in Rao's honor, and with his permission, in the year 2000. It was established "to recognize writers and scholars who have made an out standing contribution to the Literature and Culture of the South Asian Diaspora."[11][12] The award was administered by the Samvad India Foundation, a nonprofit charitable trust named for the Sanskrit word for dialogue, which was established by Makarand Paranjape of Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi to bestow the award and to promote education and cultural contributions to India and the South Asian diaspora.[11] No cash prize was attached to the award during its existence.[11] The Award was bestowed seven times between 2000 and 2009.

The inaugural recipient of the Award was K. S. Maniam of Malaysia, who was bestowed the award in 2000.[13][14] Other recipients were Yasmine Gooneratne of Sri Lanka,[15][16] Edwin Thumboo of Singapore,[17][18][19] Harsha V. Dehejia of Canada,[11][20] David Dabydeen of Guyana,[21][22] Varadaraja V. Raman of the United States,[23][24][25] and Vijay Mishra of Fiji.[26][27] Meenakshi Mukherjee, chair of the last awarding jury, died in 2009, and the award was discontinued that same year,[27] and has not since been bestowed.

Those who served as jurors for selection of the recipient included Meenakshi Mukherjee (Chair),[28] Braj Kachru,[16] Victor Ramraj,[29][28] and Makarand Paranjape[28]

Kanthapura

[edit]Raja Rao's first and best-known novel, Kanthapura (1938), is the story of a south Indian village named Kanthapura. The novel is narrated in the form of a Sthala Purana by an old woman of the village, Achakka. Dominant castes like Brahmins are privileged to get the best region of the village, while lower castes such as Pariahs are marginalized. Despite this classist system, the village retains its long-cherished traditions of festivals in which all castes interact and the villagers are united. The village is believed to be protected by a local deity named Kenchamma.

The main character of the novel, Moorthy, is a young Brahmin who leaves for the city to study, where he becomes familiar with Gandhian philosophy. He begins living a Gandhian lifestyle, wearing home-spun khaddar and discarded foreign clothes and speaking out against the caste system. This causes the village priest to turn against Moorthy and excommunicate him. Heartbroken to hear this, Moorthy's mother Narasamma dies. After this, Moorthy starts living with an educated widow, Rangamma, who is active in India’s independence movement.

Moorthy is then invited by Brahmin clerks at the Skeffington coffee estate to create an awareness of Gandhian teachings among the pariah coolies. When Moorthy arrives, he is beaten by the policeman Bade Khan, but the coolies stand up for Moorthy and beat Bade Khan - an action for which they are thrown out of the estate. Moorthy continues his fight against injustice and social inequality and becomes a staunch ally of Gandhi. Although he is depressed over violence at the estate, he takes responsibility and goes on a three-day fast and emerges morally elated. A unit of the independence committee is formed in Kanthapura, with office bearers vowing to follow Gandhi's teachings under Moorthy's leadership.

The British government accuses Moorthy of provoking the townspeople to inflict violence and arrests him. Though the committee is willing to pay his bail, Moorthy refuses their money. While Moorthy spends the next three months in prison, the women of Kanthapura take charge, forming a volunteer corps under Rangamma's leadership. Rangamma instills a sense of patriotism among the women by telling them stories of notable women from Indian history. They face police brutality, including assault and rape, when the village is attacked and burned. Upon Moorthy's release from prison, he has lost his faith in Gandhian principles as he sees most of the land of his village has been sold to city dwellers of Bombay and the village has changed beyond repair.

Bibliography

[edit]Fiction: Novels

- Kanthapura (1938), Orient Paperbacks ISBN 978-81-222010-5-5

- The Serpent and the Rope (1960), Penguin India ISBN 978-01-434223-3-4

- The Cat and Shakespeare: A Tale of India (1965) Penguin India ISBN 978-01-434223-2-7

- Comrade Kirillov (1976), Orient Paperbacks ISBN 978-08-657808-0-4

- The Chessmaster and His Moves (1988), Orient Paperbacks ISBN 978-81-709402-1-0

Fiction: Short story collections

- The Cow of the Barricades (1947)

- The Policeman and the Rose (1978)

- On the Ganga Ghat (1989), Orient Paperbacks (Vision Books) ISBN 978-81-709405-0-0

Non-fiction

- Changing India: An Anthology (1939)

- Tomorrow (1943–44)

- Whither India? (1948)

- The Meaning of India, essays (1996), Penguin India

- The Great Indian Way: A Life of Mahatma Gandhi, biography (1998), Orient Paperbacks ISBN 978-81-709430-8-2

Anthologies

- The Best of Raja Rao (1998)

- 5 Indian Masters (Raja Rao, Rabindranath Tagore, Premchand, Dr. Mulk Raj Anand, Khushwant Singh) (2003).

- Indian Ethos and Western Encounter in Raja Rao's Fiction - Editor : Dr. Madhulika Singh - Published by Rajmangal Publishers.

Awards

[edit]- 1963: Sahitya Akademi Award

- 1969: Padma Bhushan, India's third highest civilian award[30]

- 1988: Neustadt International Prize for Literature

- 2007: Padma Vibhushan, India's second highest civilian award

See also

[edit]- List of Indian writers

- Katha Upanishad, ancient Hindu text containing the razor's edge metaphor used by Rao, and others:

- For example, Somerset Maugham's novel, The Razor's Edge

References

[edit]- ^ "Conferred Sahitya Academy Award in 1964".

- ^ "University of Texas acquires Raja Rao's archive". The Hindu. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Success stories of a few Indians in America". India Today. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Alterno, Letizia (17 July 2006). "Raja Rao: An Indian writer using mysticism to explore the spiritual unity of cast and west". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

Born in Hassan, Mysore (now Karnataka), the Kannada Brahmin proudly belonged to ....

- ^ "Interview with Novelist Hassan K Raja Rao by Prof C D Narasimhaiah (From the Archival of AIR Mysuru) - YouTube". YouTube. 11 July 2021.

- ^ Ahmed Ali, "Illusion and Reality": The Art and Philosophy of Raja Rao, Journal of Commonwealth Literature, Leeds, July 1968, No.5.

- ^ "Editing Raja Rao". The Hindu. 29 July 2006. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ Prasad, Sanjiv Nandan (2019). "Raja Rao: Kanthapura". Contemporary Indian Writing in English (PDF). New Delhi: VIKAS Publishing House; Venkateshwara Open University. pp. 158–159. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Noted author Raja Rao passes away". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ^ "Raja Rao passes away". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 July 2006. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- ^ a b c d "Preserving a culture under attack," The Ottawa Citizen, Ottawa, Canada, 4 Oct. 2003, P. C3.

- ^ Shalini Dube, Indian diasporic literature: text, context and interpretation, Shree Publishers & Distributors, 2009 p. 114.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (28 October 2000). "The Indo-Malaysian connection". Tribune of India.

- ^ "Raja Rao Annual Award 2000". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Nicholas Birns, Rebecca McNeer, A Companion to Australian Literature Since 1900, 2007, page 107.

- ^ a b "Raja Rao Annual Award 2001". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Jonathan Webster, Understanding Verbal Art: A Functional Linguistic Approach, Springer, 2014, page 125.

- ^ Mallya, Vinutha (23 December 2018). "Country Poet". Pune Mirror.

- ^ "Raja Rao Annual Award 2002". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Raja Rao Annual Award 2003". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Brian Shaffer, editor, The Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Fiction, 2011, page 1035.

- ^ "Raja Rao Annual Award 2004". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ Makarand Paranjape, Science and Spirituality in Modern India, Samvad India Foundation, in association with Centre for Indic Studies, University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, 2006, page xiii.

- ^ Gawlowicz, Susan (10 April 2012). "RIT Lecture Addresses Science and Religion in Today's World". Rochester Institute of Technology.

- ^ "Raja Rao Annual Award 2006". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "Raja Rao Annual Award 2008". Samvad India. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b Ulagam, Astro (28 April 2019). "KS Maniam: Malaysia's soil is so accommodative to us; why can't we be the same to each other?". Astro Awani.

- ^ a b c "Jury for the Award". Samvad India Foundation. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ McCallum, Pamela (July 2014). "In Memoriam: Victor J. Ramraj". ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature. 45 (3): 1–2. doi:10.1353/ari.2014.0020. S2CID 162783150.

- ^ "Padma Awards" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Mercanti, Stefano (2009). The Rose and the Lotus: Partnership Studies in the Works of Raja Rao. Brill. ISBN 978-90-420-2834-0.

- Assisi, Francis C. (2006). "Breathing India in America: A Tribute to Raja Rao". IndoLink.

- "To Raja Rao", a 1969 poem by Czeslaw Milosz, the Nobel laureate's only English poem.

- Singh, Madhulika (2023). Indian Ethos and the Western Experience: A Study of the East-West Encounter in Raja Rao’s Fiction. Rajmangal Publishers. Aligarh. ISBN : 978-9394920408. URL: https://www.rajmangalpublishers.com/product-page/indian-ethos-and-western-encounter-in-raja-rao-s-fiction

External links

[edit]- Raja Rao Website, sponsored by the Raja Rao Publication Project at the University of Texas.

- Petri Liukkonen. "Raja Rao". Books and Writers.

- Aikant, Satish. (11 July 2006) [First published 23 January 2004]. "Raja Rao". The Literary Encyclopedia.

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in literature & education

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in literature & education

- 1908 births

- 2006 deaths

- 20th-century Indian short story writers

- Indian male novelists

- Aligarh Muslim University alumni

- Kannada people

- People from Hassan

- English-language writers from India

- Recipients of the Sahitya Akademi Award in English

- 20th-century Indian novelists

- Novelists from Karnataka

- Indian male short story writers

- 20th-century Indian male writers

- Indian emigrants to the United States

- American male novelists

- 20th-century American novelists

- University of Texas at Austin faculty

- American male short story writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American short story writers