Fear of a Black Planet

| Fear of a Black Planet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | April 10, 1990 | |||

| Recorded | June 1989–February 1990[1] | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 63:21 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | The Bomb Squad | |||

| Public Enemy chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Fear of a Black Planet | ||||

| ||||

Fear of a Black Planet is the third studio album by American hip hop group Public Enemy. It was released on April 10, 1990, by Def Jam Recordings and Columbia Records, and produced by the group's production team The Bomb Squad, who expanded on the sample-layered sound of Public Enemy's previous album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988). Having fulfilled their initial creative ambitions with that album, the group aspired to create what lead rapper Chuck D called "a deep, complex album". Their songwriting was partly inspired by the controversy surrounding member Professor Griff's anti-Semitic public comments and his consequent dismissal from the group in 1989.

Reflecting its confrontational tone, Fear of a Black Planet features elaborate sound collages that incorporate varying rhythms, numerous samples, media sound bites, and eccentric loops. Recorded during the golden age of hip hop, its assemblage of reconfigured and recontextualized aural sources took advantage of creative freedom that existed before the emergence of a sample clearance system in the music industry. Thematically, Fear of a Black Planet explores organization and empowerment within the black community, social issues affecting African Americans, and race relations at the time. Its critiques of institutional racism, white supremacy, and the power elite were partly inspired by Dr. Frances Cress Welsing's views on color.

A commercial and critical hit, Fear of a Black Planet sold two million copies in the United States and received rave reviews from critics, many of whom named it one of the year's best albums. Its success contributed significantly to the popularity of Afrocentric and political subject matter in hip hop and the genre's mainstream resurgence at the time. Since then, it has been viewed as one of hip hop's greatest and most important records, as well as being musically and culturally significant. In 2004, the Library of Congress added it to the National Recording Registry. In 2020, Fear of a Black Planet was ranked number 176 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Background

[edit]In 1988, Public Enemy released their second album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back to critical and commercial success.[7] Their music's dense textures, provided by the group's production team The Bomb Squad, exemplified a new production aesthetic in hip hop.[8][9][10] The controversial, politically charged lyrics by the group's lead rapper Chuck D, whose braggadocio raps contained references to political figures such as Assata Shakur and Nelson Mandela, as well as endorsements of Nation of Islam-leader Louis Farrakhan, intensified the group's affiliation with black nationalism and Farrakhan.[9]

It Takes a Nation's success helped raise hip hop's profile as both art and sociopolitical statement, amid media criticism of the genre.[11][12] It helped give hip hop a critical credibility and standing in the popular music community after it had been largely dismissed as a fad since its introduction at the turn of the 1980s.[12] In promoting the record, Public Enemy expanded their live shows and performing dynamic.[7] With the album's content and the group's rage-filled showmanship in concert, they became the vanguard of a movement in hip hop that reflected a new black consciousness and socio-political dynamic that were taking shape in America at the time.[13]

In May 1989, Chuck D, Bomb Squad producer Hank Shocklee, and Def Jam executive Bill Stephney were negotiating with several labels for a production deal from a major record company, their goal since starting Public Enemy in the early 1980s.[12] As they were in negotiations, group member Professor Griff made anti-Semitic remarks in an interview with The Washington Times,[12] in which he said that Jews were the cause of "the majority of the wickedness" in the world.[14] Public Enemy received media scrutiny and criticism from religious organizations and liberal rock critics,[15] which added to charges against the group's politics being racist, homophobic, and misogynistic.[14][16]

Amid the controversy, Chuck D was given an ultimatum by Shocklee and Stephney to dismiss Griff from the group or the production deal would fall through.[12] He fired Griff in June, but he later rejoined and has since denied holding anti-Semitic views and apologized for the remarks.[14][17] Several people who had worked with Public Enemy expressed concern about Chuck D's leadership abilities and role as a social spokesman.[12] Def Jam director of publicity Bill Adler later said that the controversy "partly ... fueled the writing of [the album]".[18]

To follow up It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, the group sought to make a more thematically focused work and to condense Dr. Frances Cress Welsing's theory of "Color Confrontation and Racism (White Supremacy)" into an album-length recording. According to Chuck D, this involved "telling people, well, color's an issue created and concocted to take advantage of people of various characteristics with the benefit of a few".[18] He recalled their concept for the album in an interview with Billboard: "We wanted really to go with a deep, complex album ... more conducive to the high and lows of great stage-performance."[18] Chuck D also cited the commercial circumstances for hip hop at the time, having quickly transitioned from a singles to an album medium in the music industry during the 1980s.[19] In an interview for Westword, he later said, "We understood the magnitude of what an album was, so we set out to make something that not only epitomized the standard of an album, but would stand the test of time by being diverse with sounds and textures, and also being able to home in on the aspect of peaks and valleys".[19]

Recording and production

[edit]We wanted to create a new sound out of the assemblage of sounds that made us have our own identity. Especially in our first five years, we knew that we were making records that will stand the test of time. When we made It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back we were shooting to make What's Going On by Marvin Gaye and when we made Fear of a Black Planet I was shooting for Sgt. Pepper's.

Fear of a Black Planet was recorded at three studios—Greene St. Recording in New York City, The Music Palace in West Hempstead, and Spectrum City Studios in Hempstead—from June to October 1989. It was produced by The Bomb Squad—Chuck D, Eric "Vietnam" Sadler, Keith Shocklee, and his brother Hank Shocklee[21]—while Chuck D called Hank, their director, "the Phil Spector of hip-hop".[20] Keith, significant in composing the main tracks and music,[22] received here his first official credit as a team member.[23] For the album, they sought to expand on the dense, sample-layered "wall of noise" of Public Enemy's prior album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.[24][25][26]

Employing an elaborate method, the Bomb Squad reconfigured and recontextualized disparate sound fragments, while expanding their repertoire of samples to radio and other sources.[20] According to Shocklee, "When you're talking about the kind of sampling that Public Enemy did, we had to comb through thousands of records to come up with maybe five good pieces. And as we started putting together those pieces, the sound got a lot more dense."[20] Hank Shocklee called it "a production assembly line where each person had their own particular specialty ... [Shocklee] came from a DJ's perspective. Eric [Sadler] is coming from a musician's perspective."[20] Sadler's approach was more traditional and structured, while Shocklee's was more experimental.[20] As the main lyricist, Chuck D wanted to recontextualize the sampled material into his lyrics and create a theme.[20]

The Bomb Squad used devices including the E-mu SP-1200 drum machine and sampler, the Akai S900 sampler, and a Macintosh computer.[27] Chuck D remarked that "95 percent of the time it sounded like mess. But there was 5 percent of magic that would happen."[20] Shocklee compared their production to filmmaking, "with different lighting effects, or film speeds, or whatever", while Chuck D analogized to an artist creating green from yellow and blue.[20] As he had the production team improvise beats, much of the album was composed on the spot.[22] In a 1990 interview, Chuck added, "We approach every record like it was a painting. Sometimes, on the sound sheet, we have to have a separate sheet just to list the samples for each track. We used about 150, maybe 200 samples on Fear of a Black Planet."[28]

To synchronize the samples, the Bomb Squad used SMPTE timecodes and arranged and overdubbed parts of backing tracks, which had been inspected by the members for snare, bass, and hi-hat sounds.[27] Chuck D said, "Our music is all about samples in the right area, layers that pile on each other. We put loops on top of loops on top of loops, but then in the mix we cut things away."[27] Their production was innovative, according to journalist Jeff Chang. "They're figuring out how to jam with the samples and to create these layers of sound," Chang said. "I don't think it's been matched since then."[20] After the tracks were completed, the Bomb Squad began sequencing what was at first a seemingly discontinuous album, amid internal disputes.[29] Final mixing took place at Greene St. Recording and lasted until February 1990.[12] According to Sadler, "a lot of people were like, 'Wow, it's a brilliant album'. But it really shoulda been much better. If we had more time and we didn't have to deal with the situation of nobody talking".[29]

Fear of a Black Planet was conceived during the golden age of hip hop, a period roughly between 1987 and 1992 when artists took advantage of emerging sampling technology before record labels and lawyers took notice.[20] Accordingly, Public Enemy were not compelled to obtain sample clearance for the album.[20] This preceded the legal limits and clearance costs later placed on sampling,[30] which limited hip hop production and the complexity of its musical arrangements.[20] In an interview with Stay Free!, Chuck D said: "Public Enemy's music was affected more than anybody's because we were taking thousands of sounds. If you separated the sounds, they wouldn't have been anything--they were unrecognizable. The sounds were all collaged together to make a sonic wall."[31] An analysis by law professors Peter DiCola and Kembrew McLeod estimated that under the sample clearance system that developed after the album's release, Public Enemy were to lose at least five dollars per copy if they were to clear the album's samples at 2010 rates, a loss of five million dollars on a platinum record.[32]

For the track "Burn Hollywood Burn", Chuck D dealt with clearance issues from different record labels to collaborate with rappers Big Daddy Kane and Ice Cube, who had been pursuing the Bomb Squad to produce his debut album.[33] The recording marked one of the first times in which MCs from different rap crews collaborated,[33] and it led to the Bomb Squad working with Ice Cube on his 1990 debut album AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted.[34]

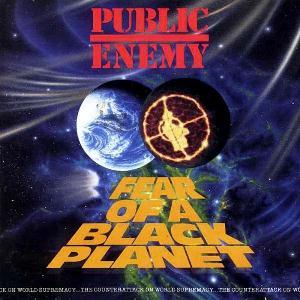

For the album's artwork, Public Enemy enlisted B.E. Johnson, a NASA illustrator.[18] His design illustrated Chuck D's concept of two planets, the "Black" planet and Earth, eclipsing.[18] Cey Adams, creative director for Def Jam at the time, said: "It was so interesting to me that a black hip-hop act did an illustration for their album cover. At that time, black hip-hop artists, for the most part, had photos of themselves on their covers. But this was the first time someone took a chance to do something in the rock'n'roll vein".[18]

Music

[edit]Hip hop does not simply draw inspiration from a range of samples, but it layers these fragments into an artistic object. If sampling is the first level of hip hop aesthetics, how the pieces or elements fit together constitute the second level. Hip hop emphasizes and calls attention to its layered nature. The aesthetic code of hip hop does not seek to render invisible the layers of samples, sounds, references, images, and metaphors. Rather, it aims to create a collage in which the sampled texts augment and deepen the song/book/art's meaning to those who can decode the layers of meaning.

—Richard Schur, "Hip Hop Aesthetics"[35]

Fear of a Black Planet's music features assemblage compositions that draw on numerous sources.[20] The production's musique concrète-influenced approach reflects the political and confrontational tones of the group's lyrics, with sound collages that feature varying rhythms, aliased or scratchy samples, media sound bites, and eccentric music loops.[36] Recordings sampled for Fear of a Black Planet include those from funk, soul, rock, and hip hop genres.[28] Elements such as choruses, guitar sounds, or vocals from sampled recordings are reappropriated as riffs in songs on the album, while sampled dialogue from speeches is incorporated to support Chuck D's arguments and commentary on certain songs.[14] The Bomb Squad's Hank Shocklee compared their produced sounds, surrounding Chuck D's rhythmic, exhortative baritone voice, to putting "the voice of God in a storm".[37]

According to The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Folklore (2006), Fear of a Black Planet introduced a production style that "borrowed elements from jazz, especially that of John Coltrane, to craft a soundscape that was more challenging than that of their previous two albums, but still complemented the complex social commentary".[38] Journalist Kembrew McLeod called the music "both agitprop and pop, mixing politics with the live-wire thrill of the popular music experience", adding that the Bomb Squad "took sampling to the level of high art while keeping intact hip hop's populist heart. They would graft together dozens of fragmentary samples to create a single song collage."[20] Simon Reynolds said it was "a work of unprecedented density for hip hop, its claustrophobic, backs-against-the-wall feel harking back to Sly Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On or even Miles Davis' On the Corner".[39]

Some tracks used elements from Public Enemy's previous material, which Pete Watrous of The New York Times interpreted as a dual reference to hip hop tradition and the history of the group.[14] Watrous described the music as "the sound of urban alienation, where silence doesn't exist and sensory stimulation is oppressive and predatory", and writes that its dense textures "envelop Chuck D's voice and make his rapping sound as if it is under duress, as if he were fighting against a background intent on taking him over ... Layer after layer of sounds are placed on top of each other until the music becomes nearly tactile".[14] Chuck D called Fear of a Black Planet a record entirely of "found sounds ... probably the most elaborate smorgasbord of sound that we did ... When we put together our music, we try to put together layers that complement each other, and then the voice tries to complement that, and the theme tries to complement that, and then the song itself tries to complement the album as a whole, fitting into the overall context."[28] In his essay on hip hop aesthetics, Richard Schur interpreted such layering as a motif in hip hop and as "the process by which ... new meanings are created and communicated, primarily to an equally knowledgeable audience", concluding that "Public Enemy probably took the ideal of layering to its farthest point".[35]

Lyrics

[edit]Fear of a Black Planet contains themes of organization and empowerment within the African-American community,[40] and of confrontation.[41] Chuck D's critical lyrics on the album, interspersed with the surrealism of Flavor Flav,[42] also concern contemporary black life, the state of race relations,[43] and criticisms of institutional racism, White supremacy, and the power elite.[44] Greg Sandow called Chuck D's language "strong and elusive, often fragmentary" and "embedded [with] critical, sometimes brutal thoughts". Although he viewed that "some people might disagree with some of these ideas", Sandow wrote that "it's hard to dispute the lyrics' assertion that many Whites are afraid of blacks", adding that the album "touches on" the idea of "an age when whites understand that they're a minority in the world".[43] Robert Hilburn believed that the songs "decried what Chuck D. saw as the consequences of white, European cultural domination in the United States and throughout much of the world".[17] Sputnikmusic's Nick Butler observed "two recurring themes – inter-racial relationships ... and the racism inherent in the American media".[42]

In his book Somebody Scream!: Rap Music's Rise to Prominence in the Aftershock of Black Power, Marcus Reeves said that Fear of a Black Planet "was as much a musical assault on America's racism as it was a call to blacks to effectively react to it".[40] According to Greg Kot, the album was "hardly a black power manifesto for world domination, but a statement about racial paranoia. Though he spares virtually no one with his withering raps, Public Enemy's Chuck D is harshest of all on his fellow blacks, expounding on everything from history to fashion: Use your brain instead of a gun. Drugs are death. Know your past so you won't screw up the future. Gold chains worn around the neck demean the brotherhood in South Africa."[45] Kot wrote of Chuck D's perspective and the theme of fear, "It's fear that divides us, he says; understand me better and you won't run. Fear of a Black Planet is about achieving that understanding, but on Public Enemy's terms. In presenting their view of life from an Afro-centric, as opposed to Euro-centric, perspective, P.E. challenges listeners to step into their world."[46]

Songs

[edit]The opening track, "Contract on the World Love Jam", is a sound collage made up of samples, scratch cuts,[49] and snippets recorded by Chuck D from radio stations and sound bites of interviews and commercials.[50] The tension-building track introduces the album's dense, sample-based production.[49] According to Chuck D, the song features "about forty-five to fifty [sampled] voices" that interweave as part of an assertive sonic collage and underscore the themes explored on subsequent tracks.[20] "Incident at 66.6 FM", another collage that segues into "Welcome to the Terrordome", contains snippets from a radio call-in show interview of Chuck D and alludes to the media persecution perceived by Public Enemy.[14][17]

The controversial "Welcome to the Terrordome" references the murder of Yusef Hawkins and the 1989 riots in Virginia Beach, and criticizes Jewish leaders who protested Public Enemy in response to Professor Griff's anti-Semitic remarks.[40][51] Chuck D addresses the controversy from the perspective of someone in the center of political turmoil, with criticisms of the media and references to the Crucifixion of Jesus: "Crucifixion ain't no fiction / So called chosen frozen / Apology made to who ever pleases / Still they got me like Jesus".[14][44] He is also critical of Blacks and those who "blame somebody else when you destroy yourself": "Every brother ain't a brother / 'cause a Black hand squeezed on Malcolm X the man / the shootin of Huey Newton / from the hand of Nig who pulled the trigger".[44] His lyricism features dizzying rap patterns and internal rhyme: "Lazer, anastasia, maze ya / Ways to blaze your brain and train ya ... Sad to say I got sold down the river / Still some quiver when I deliver / Never to say I never knew or had a clue / Word was heard, plus hard on the boulevard / Lies, scandalizin', basin' / Traits of hate who's celebratin' wit Satan?".[47] Among the samples used for the song are several James Brown tracks and the guitar line from The Temptations' "Psychedelic Shack".[47] Several other samples are heard amid Chuck D's rapping, such as the line "come on, you can get it-get it-get it" from Instant Funk's "I Got My Mind Made Up (You Can Get It Girl)".[47] AllMusic's John Bush cites the track as "the production peak of the Bomb Squad and one of Chuck D.'s best rapping performances ever ... [N]one of their tracks were more musically incendiary".[47]

"Burn Hollywood Burn" assails the use of black stereotypes in movies, while "Who Stole the Soul?" condemns the music industry's exploitation of black recording artists and calls for reparations.[17][40] "Revolutionary Generation" celebrates the strength and endurance of black women with lyrics related to black feminism,[44] an unfamiliar topic in contemporary hip hop.[52][53] It also addresses sexism within the black community and misogyny in hip hop culture.[42] The title track discusses racial classification and the origins of Whites fearing African Americans, particularly racist concerns by some Whites over the effect of miscegenation.[14][40] In the song, Chuck D argues that they should not worry because the original man was black and "white comes from black / No need to be confused".[14] The song features a vocal sample of comedian and activist Dick Gregory saying, "Black man, black woman, black baby / white man, black woman, black baby?".[14] "Pollywanacraka" also concerns interracial relations,[53] including Blacks who leave their communities to marry wealthy Whites,[43] and societal views of the matter: "This system had no wisdom / The devil split us in pairs / and taught us white is good, black is bad / and black and white is still too bad".[42] "Meet the G That Killed Me" features homophobic etiology and condemns homosexuality: "Man to man / I don't know if they can / From what I know / The parts don't fit".[14][52]

Songs such as "Fight the Power", "Power to the People", and "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" propose a response for African Americans to the issues criticized throughout the album.[40] "Power to the People" has a tempo of approximately 125 beats per minute, fast-paced Roland TR-808 drum machine patterns, and elements of Miami bass, electro-boogie.[50] Addressing their plight at the turn of the 1990s,[54] "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" features cacophonic sound textures and a theme of unity among African Americans,[55] with Chuck D preaching "Brothers that try to work it out / They get mad, revolt, revise, realize / They're superbad / Small chance a smart brother's gonna be a victim of his own circumstance".[56][57] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post writes that songs such as "War at 33⅓" and "Fight the Power" "may sound like a call to ohms and arms, but they are really a call to action ('turn us loose and we shall overcome'), a message to conscience and a plea for unity ('move as team, never move alone,' both cautionary advice and game plan)".[44] "War at 33⅓" has a theme of resistance and a 128 bpm-tempo,[55] cited by Chuck D as "the fastest thing I've ever rapped to, rapping right on top of the beat".[50]

"Fight the Power" features revolutionary rhetoric by Chuck D and was used by director Spike Lee as a leitmotif in his acclaimed 1989 film Do the Right Thing, a film about racial tension in a Brooklyn neighborhood.[14] Lee approached the group in 1988 after the release of It Takes a Nation with the proposition of making a song for his movie.[7] Chuck D wrote most of the song attempting to adapt The Isley Brothers' "Fight the Power" to a modernist perspective.[58] The song's third verse contains disparaging lyrics about popular American icons Elvis Presley and John Wayne,[59] as Chuck D rhymes "Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant shit to me' / Straight up, racist the sucker was / Simple and plain", with Flavor Flav following, "Muthafuck him and John Wayne!".[60] The lyrics, which shocked and offended many listeners at the time,[60] express the identification of Presley with racism — either personally or symbolically — and the largely held notion among Blacks that Presley — whose musical and visual performances owed much to African-American sources — unfairly achieved the cultural acknowledgment and commercial success largely denied his black peers in rock and roll.[59][61] The line regarding John Wayne refers to his controversial personal views, including racist remarks made in his 1971 interview for Playboy.[59] "Fight the Power" has since become the group's best-known song and has been named one of the best songs of all time by numerous publications.[7]

Written by Flavor Flav, Shocklee, Sadler, "911 Is a Joke" features Flav as the main vocalist and criticizes the inadequacy of 9-1-1[53] — the emergency telephone number used in the United States[62] — and the lack of police response to emergency calls in predominantly African-American neighborhoods.[14] The song originated from Chuck D's suggestion for Flavor Flav to write a song. As Flav recalled, "I went and got high and wrote the record. I went and got ripped, I went and got out of my mind, and I started speaking all kinds of crazy shit 'cos usually back in the days when I used to smoke, it used to broaden my ideas and everything".[63] The humorous and satirical subject matter is reflected in the song's accompanying music video, which features a severely injured Flav being mistreated by a remiss, overdue ambulance staff.[63] Another Flavor Flav-solo performance, "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man", has lyrics advocating African-American self-reliance and denouncing welfare dependence.[33][64] It also reflects on Flav's experiences with acquaintances from poor neighborhoods.[33] He said of his inspiration for the song, "I was in my Corvette riding from Long Island going to The Bronx. I was slipping. I was roasting. I mean I was smoked-out crazy. And everybody kept asking me for stuff and yet nobody wanted to give me stuff. So then if anybody ever asked me for something I would be like, 'Yo, I can't do nothing for ya man.' Next thing you know I started to vibe on it: 'I can't do nothing for ya man,' um ahh um um ahh. So I went and told that to Chuck. Chuck was like, 'Record that shit man'".[33] According to Tom Moon, on both of the album's Flavor Flav songs, the rapper "affects a tone of gimme-a-break sarcasm that is crucial to both tracks, and is welcome respite from Chuck D.'s assault".[64]

Marketing and sales

[edit]Originally intended for an October 1989 release date,[65] Fear of a Black Planet was released on April 10, 1990, by Def Jam Recordings and Columbia Records.[66] Although It Takes a Nation garnered Public Enemy more exposure with black audiences and music journalists, urban radio outlets had mostly rejected Def Jam's requests to include the group's singles in their regular rotation.[67] This incited Def Jam co-founder Russell Simmons to attempt grassroots promotional tactics from his earlier years of promoting hip hop shows. In promoting Fear of a Black Planet, he recruited young street crews to put up posters, billboards, and stickers on public surfaces,[68] while Simmons himself met with nightclub DJs and college radio program directors to persuade them to add albums tracks such as "Fight the Power", "Welcome to the Terrordome", and "911 Is a Joke" to their playlists.[69] As singles, they were released on July 4, 1989,[70] in January 1990, and in April, respectively. Two more singles were later released — "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" in June and "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man" in October,[71] with the latter also featured in the 1990 comedy film House Party.[33]

Fear of a Black Planet debuted at number 40 on the Billboard Top Pop Albums chart.[72] It also charted for 10 weeks and reached number four in the United Kingdom,[73] while in Canada, it charted for 28 weeks and reached number 15.[74][75] By July 1990, it had sold 1.5 million copies in the US,[76] where it ultimately peaked at number 10 and charted for 27 weeks on the Top Pop Albums.[77] After 1991, when the tracking system Nielsen SoundScan began tracking domestic sales data, Fear of a Black Planet sold 561,000 additional copies by 2010.[18]

The controversy surrounding the group and their exposure through the singles "Fight the Power" and "Welcome to the Terrordome" helped Fear of a Black Planet exceed the sales of their previous two albums, Yo! Bum Rush the Show and It Takes a Nation of Million to Hold Us Back at the time,[78] 500,000 and 1.1 million copies, respectively.[14] The latter single's lyrics were initially viewed by religious groups and the media as anti-semitic upon its release.[14][44] The album contributed to hip hop's commercial breakthrough at the beginning of the 1990s, despite its limited radio airplay.[79][80][81] Its success made Public Enemy the top-selling act, both domestically and internationally, for Def Jam Recordings at the time.[69] Ruben Rodriguez, Columbia's senior vice president at the time, said in one of the label's press releases, "What's happening with Public Enemy is unbelievable. The album is selling across the board to all demographics and nationalities".[15] In a December 1990 article, Chicago Sun-Times writer Michael Corcoran discussed Public Enemy's commercial success with the album and remarked that "more than half of the 2 million fans who bought [Fear of a Black Planet] are white".[82]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[43] |

| NME | 10/10[83] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Village Voice | A−[52] |

Fear of a Black Planet was met with rave reviews from critics.[85] After asserting prior to its release that it was "bound to be one of the most dissected pop collections in years",[12] Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the album "rivals the force and the power of It Takes a Nation" while "maintaining commercial and artistic credibility in the fast-changing rap world" with original music.[17] USA Today's Edna Gundersen called it "a masterpiece of innovation [and] challenging music" that makes the group's pro-black lyrics more interesting and plausible.[53] Rolling Stone magazine's Alan Light praised Public Enemy's self-assured and realistic lyrics, and viewed the album as a deeper, more focused version of "the careening rage of Nation of Millions".[80] Greg Sandow of Entertainment Weekly found it powerfully relevant to contemporary American culture and unparalleled by anything in popular music: "It sounds like a partly African, partly postmodern collage, stitched together on tumultuous urban streets."[43] Tom Moon of The Philadelphia Inquirer observed "some of the genre's most sophisticated sound designs and unconventionally agile rapping" on the album and called it "a major piece of work, the first hard evidence of rap's maturity and a measure of its continuing relevance".[64]

In The Washington Post, Richard Harrington said because Fear of a Black Planet is a challenging listen, "How it's met depends on how it's understood."[44] Robert Christgau, writing for The Village Voice, felt that its "brutal pace" loses momentum and that the group's lyrics are ideologically flawed, but wrote that although their "rebel music" is gimmicky, "this is show business, and they're still smarter and more daring than anybody else working their beat."[52] Peter Watrous of The New York Times called it "an essential pop album" and stated, "On their own, the lyrics seen [sic] functional. Taken with the music, they bloom with meaning."[14] Simon Reynolds of Melody Maker remarked that the content epitomizes the group's significance at the time: "Public Enemy are important ... because of the angry questions that seethe in their music, in the very fabric of their sound; the bewilderment and rage that, in this case, have made for one hell of strong, scary album".[39] Chicago Tribune critic Greg Kot felt that with the album, "Public Enemy affirms that it is not just a great rap group, but one of the best rock bands on the planet-black or otherwise".[46]

At the end of 1990, Fear of a Black Planet appeared in the top-10 of several critics' lists of the year's best albums.[82][86] It was voted the third best record of 1990 in The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics' poll,[87] and the publication's Robert Christgau ranked it number 10 on his own "Dean's list".[88] It was named the second best album of the year by The Boston Globe,[89] the third best by USA Today,[90] and fifth best by the Los Angeles Times's Robert Hilburn, who wrote that it "dissects aspects of the black experience with an energy and vision that illustrates why rap continues to be the most creative genre in pop".[91] The State named it one of the year's best albums and hailed it as "possibly the boldest and most important rap record ever made. A sonic tour de force".[92] Fear of a Black Planet was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group, presented at the 33rd Grammy Awards in 1991.[93]

Legacy and influence

[edit]The music outdistances other political pop with both its urgency and its visionary approach to the dance floor. And the group has made pop music that is vital in the contemporary debate about race in American culture for the first time since the 1960s, when Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown, Gil Scott-Heron, the Last Poets and others charged their music with politics. Unthinkable without the context of racial strife, Public Enemy is a voice for the traditionally voiceless black lower-middle class. What is extraordinary is how the group has managed to turn the specifics of their social position, as both blacks and entertainers, into music. By including facts and figures from their lives in their pieces, they've folded the real into their storytelling.

—The New York Times, 1990[14]

Fear of a Black Planet's success with critics and consumers was viewed as a significant factor to hip hop's mainstream emergence in 1990, which Billboard editor Paul Grein said was "the year that rap exploded".[86] In a July 1990 article, Kot compared Public Enemy's influence on hip hop with the album at the start of the 1990s to the impact of Bob Dylan, George Clinton, and Bob Marley on each of their respective genres and eras, having "given it legitimacy and authority far beyond its core following".[76] Chuck D later said of the album in retrospect, "If It Takes a Nation was our 'nation' record, Fear of a Black Planet was our 'world' record".[18] With respect to hip hop, the album was important in the field of sampling, as copyright lawyers took notice of The Bomb Squad's production and such a sample-heavy work would not be cost effective in the future.[29] Chuck D later said of its sampling issues, "We got sued for everything. We knew that the door on sampling was gonna close".[29] Subsequent use of sampled material, particularly the use of whole songs on top of a beat, by other hip hop artists prompted stricter sampling laws.[29] Fear of a Black Planet was the group's commercial apex, with sales dropping off for their subsequent albums.[38] Chuck D said it was their most successful record, "not because of all the hype and hysteria. It was a world record. Because of all the different feels and the different textures and the flow it had".[94]

Fear of a Black Planet also helped popularize political subject matter in hip hop music,[14] as it epitomized the resurgence in black consciousness among African-American youths at the turn of the 1990s, amid a turbulent social and political zeitgeist during the Bush administration and South African apartheid.[95] Black consciousness became the prevailing subject matter of many hip hop acts, exemplified by X-Clan's cultural nationalism on their debut album To the East, Blackwards, the revolutionary, Black Panther-minded The Devil Made Me Do It by Paris, and the Five Percenter religious nationalism of Poor Righteous Teachers' debut Holy Intellect.[95] Christgau wrote in 1990 that Public Enemy had become not only "the most innovative popular musicians in America if not the world" but also "the most politically ambitious. Not even in the heyday of [the] Clash has any group come so close to the elusive and perhaps ridiculous '60s rock ideal of raising political consciousness with music."[96] Their music on the album inspired leftist and Afrocentric ideals among rap listeners who were previously exposed to more materialist themes in the music.[96] Reeves said it introduced black consciousness to the "hip-hop youth" of the "post-black power generation", "as leather African medallions made popular by rappers like P.E. replaced thick gold chains as the ultimate fashion statement ... P.E.'s million seller sat at the front of a full-blown black pride resurgence within rap".[95]

However, this resurgence soon became commodified as a trend, while actual awareness within the African-American community was limited and ineffectual to issues such as drug dealing and the prevalence of liquor stores in such neighborhoods.[97] Public Enemy responded to this and other deep-rooted problems of Black America on their following album, Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black (1991), which featured more critical assessments of African-Americans, denouncing Black drug dealers who donned Afrocentric merchandise, hip hop artists who promoted malt liquor, black radio stations for lacking significant airplay to hip hop, and even the Africans at the onset of the Atlantic slave trade for lacking unity.[97]

Reappraisal

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The Austin Chronicle | |

| Christgau's Consumer Guide | A[99] |

| The Guardian | |

| NME | 10/10[101] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[102] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 9/10[105] |

| Uncut | 9/10[106] |

Since Fear of a Black Planet was first released, it has been viewed by critics as one of the greatest and most important hip hop albums of all time,[30][107][108] as well as a culturally significant work.[20] Stephen Thomas Erlewine from AllMusic believed that "as a piece of music, this is the best hip-hop has ever had to offer", calling it "a remarkable piece of modern art, a record that ushered in the '90s in a hail of multi-culturalism and kaleidoscopic confusion".[30] Alex Ross cited it as one of "the most densely packed sonic assemblages in musical history",[109] while Q said it "achieved the near impossible by being every bit as good as its predecessor".[103] In the opinion of Kembrew McLeod, Public Enemy had worked with production equipment that would seem primitive decades later but still managed to invent new "techniques and workarounds that electronics manufacturers never imagined".[20] Sputnikmusic staff writer Nick Butler said the album remained an enduring and vital work in a genre that "has a habit of moving at such a pace that records date in a matter of years".[42]

In 1997, The Guardian ranked it number 50 on their 100 Best Albums Ever list, which was voted on by a panel of various artists, critics, and DJs.[110] The following year, it was selected as one of The Source's 100 Best Rap Albums.[111] In 2000, it was voted number 617 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums[112] and named in Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s as among the decade's most essential works.[113] Rolling Stone included Fear of a Black Planet on their "Essential Recording of the '90s" list,[114] and in 2003, the magazine ranked it number 300 on their list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[115] and 302 in a 2012 revised list,[116] and number 176 in a 2020 revised list.[117] The record was ranked number 21 in Spin's "100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005" publication,[118] and number 17 on Pitchfork's "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s".[119]

In 2004, the Library of Congress added Fear of a Black Planet to the National Recording Registry, which selects recordings annually that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[120] According to a press release for the registry, "'Fear of a Black Planet' brought hip-hop respect from critics, millions of new fans and passionate debate over its political content. The album signaled the coupling of a strongly political message with hip-hop music".[120] In 2013, NME named it the 96th best record ever in their all-time list.[121]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Keith Shocklee, Eric Sadler, and Carl Ridenhour unless noted otherwise. All tracks are produced by The Bomb Squad

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Contract on the World Love Jam" (Intro) | 1:44 | |

| 2. | "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" | 5:07 | |

| 3. | "911 Is a Joke" |

| 3:17 |

| 4. | "Incident at 66.6 FM" (Interlude) | 1:37 | |

| 5. | "Welcome to the Terrordome" | 5:25 | |

| 6. | "Meet the G That Killed Me" (Skit) | 0:44 | |

| 7. | "Pollywanacraka" | 3:52 | |

| 8. | "Anti-Nigger Machine" | 3:17 | |

| 9. | "Burn Hollywood Burn" (featuring Ice Cube & Big Daddy Kane) |

| 2:47 |

| 10. | "Power to the People" | 3:50 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. | "Who Stole the Soul?" | 3:49 | |

| 12. | "Fear of a Black Planet" | 3:45 | |

| 13. | "Revolutionary Generation" | 5:43 | |

| 14. | "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man" | 2:46 | |

| 15. | "Reggie Jax" (Freestyle) | 1:35 | |

| 16. | "Leave This Off Your Fuckin' Charts" (Interlude) | Norman Rogers | 2:31 |

| 17. | "B Side Wins Again" (Remix) | 3:45 | |

| 18. | "War at 33⅓" | 2:07 | |

| 19. | "Final Count of the Collision Between Us and the Damned" (Outro) | 0:48 | |

| 20. | "Fight the Power" | 4:42 | |

| Total length: | 63:21 | ||

2014 deluxe edition bonus tracks

[edit]- "Brothers Gonna Work It Out (Remix)" – 5:51

- "Brothers Gonna Work It Out (Dub)" – 5:10

- "Flavor Flav" – 0:16

- "Terrorbeat" – 3:07

- "Welcome to the Terrordome (Terrormental)" – 3:38

- "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man (Full Rub Mix)" – 4:44

- "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man (U.K. 12″ Powermix)" – 4:06

- "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man (Dub Mixx)" – 4:03

- "Burn Hollywood Burn (Extended Censored Fried to the Radio Version)" – 3:42

- "Anti-Nigger Machine (Uncensored Extended)" – 1:59

- "911 Is a Joke (Instrumental)" – 3:21

- "Power to the People (Instrumental)" – 2:42

- "Revolutionary Generation (Instrumental)" – 5:46

- "War at 33⅓ (Instrumental)" – 2:07

- "Fight the Power ("Do the Right Thing" Soundtrack Version)" – 5:23

- "Fight the Power (Powersax)" – 3:53

- "Fight the Power (Flavor Flav Meets Spike Lee)" – 4:34

- "The Enemy Assault Vehicle Mixx (Medley)" – 9:25

Personnel

[edit]Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[21]

- Agent Attitude – performer

- Kamarra Alford – assistant engineer

- Jules Allen – photography

- Big Daddy Kane – rapper

- The Bomb Squad – producer

- Mike Bona – engineer, mixing

- Brother James I – performer

- Brother Mike – performer

- Chris Champion – assistant engineer

- Chuck D – arranger, director, producer, rapper, sequencing

- Jody Clay – assistant engineer

- Tom Conway – assistant engineer

- The Drawing Board – art direction

- Paul Eulin – engineer, mixing

- Flavor Flav – rapper

- Dave Harrington – assistant engineer

- Robin Holland – photography

- Rod Hui – engineer, mixing

- Ice Cube – rapper

- James Bomb – performer

- B.E. Johnson – cover art

- Steve Loeb – engineer

- Branford Marsalis – saxophone

- Dave Patillo – assistant engineer

- Alan "JJ/Scott" Plotkin – engineer, mixing, vocals

- Professor Griff – rapper

- Eric "Vietnam" Sadler – arranger, director, programming, producer, sequencing

- Nick Sansano – engineer, mixing

- Paul Shabazz – programming

- Christopher Shaw – engineer, mixing

- Hank Shocklee – arranger, director, producer, sequencing

- Keith Shocklee – arranger, director, producer, sequencing

- James Staub – assistant engineer

- Terminator X – scratching

- Ashman Walcott – photography

- Howie Weinberg – mastering

- Russell Winter – photography

- Wizard K-Jee – scratching

- Dan Wood – engineer, mixing

- Kirk Yano – engineer

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Singles

[edit]| Year | Song | Chart | Peak position | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | "Fight the Power" | Netherlands (Nationale Hitparade)[133] | 24 | |||

| UK Singles (Gallup)[134] | 29 | |||||

| US Hot Black Singles* (Billboard)[135] | 20 | |||||

| US Hot Rap Singles (Billboard)[136] | 1 | |||||

| 1990 | "Welcome to the Terrordome" | Netherlands (Nationale Hitparade)[137] | 21 | |||

| New Zealand (RIANZ)[137] | 12 | |||||

| UK Singles (Gallup)[134] | 18 | |||||

| US Hot Dance Music/Club Play (Billboard)[138] | 49 | |||||

| US Hot R&B Singles (Billboard)[138] | 15 | |||||

| US Hot Rap Singles (Billboard)[136] | 3 | |||||

| "911 Is a Joke" | Netherlands (Nationale Hitparade)[139] | 71 | ||||

| New Zealand (RIANZ)[139] | 22 | |||||

| Switzerland (Schweizer Hitparade)[139] | 25 | |||||

| UK Singles (Gallup)[134] | 41 | |||||

| US Billboard Hot 100 Singles Sales[140] | 34 | |||||

| US Hot Dance Music/Maxi-Singles Sales (Billboard)[136] | 26 | |||||

| US Hot R&B Singles (Billboard)[141] | 15 | |||||

| US Hot Rap Singles (Billboard)[136] | 1 | |||||

| "Brothers Gonna Work It Out" | New Zealand (RIANZ)[142] | 30 | ||||

| UK Singles (Gallup)[134] | 46 | |||||

| US Hot Dance Music/Club Play (Billboard)[143] | 31 | |||||

| US Hot R&B Singles (Billboard)[143] | 12 | |||||

| US Hot Rap Singles (Billboard)[136] | 22 | |||||

| "Can't Do Nuttin' for Ya Man" | New Zealand (RIANZ)[144] | 15 | ||||

| UK Singles (Gallup)[134] | 53 | |||||

| 1991 | US Hot Rap Singles (Billboard)[136] | 11 | ||||

| * Prior to 1990, when Billboard returned to the R&B designation, the chart was called the Hot Black Singles.[145] | ||||||

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[146] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[147] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[148] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ Brian Coleman (2014-10-13). "The Making of Ice Cube's "AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted"". Medium. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ Henderson, Alex (2001). "Public Enemy - Fear of a Black Planet". In Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (eds.). All Music Guide: The Definitive Guide to Popular Music. Backbeat Books/All Media Guide. ISBN 9780879306274.

- ^ Fonseca, Anthony J. (2019). Listen to Rap! Exploring a Musical Genre. ABC-CLIO. p. 166. ISBN 978-1440865671.

- ^ Cader, Michael, ed. (2002). People: Almanac 2003. Time Home Entertainment. p. 175. ISBN 192904996X.

- ^ Pinn, Anthony (2005). "Rap Music and Its Message". In Forbes, Bruce; Mahan, Jeffrey H. (eds.). Religion and Popular Culture in America. University of California Press. p. 263. ISBN 9780520932579. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Blyweiss, Adam (August 5, 2013). "The Top 100 Hip-Hop Albums of the '90s: 1990-1994 - 1. Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Treble. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Myrie 2008, p. 121.

- ^ Christgau, Robert; Dibbell, Carola (September 1989). "Public Enemy: Fight the Power Live". Video Review. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Myrie 2008, p. 131.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1989). "The Shit Storm: Public Enemy". LA Weekly. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Reeves 2009, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hilburn, Robert (February 4, 1990). "Rap—The Power and the Controversy: Success has validated pop's most volatile form, but its future impact could be shaped by the continuing Public Enemy uproar". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Reeves 2009, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Watrous, Peter (April 22, 1990). "RECORDINGS; Public Enemy Makes Waves – and Compelling Music". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Dery 2004, p. 472.

- ^ Dery 2004, p. 473.

- ^ a b c d e Hilburn, Robert (April 10, 1990). "POP MUSIC REVIEW: Public Enemy Keeps Up Attack". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Concepcion, Mariel (March 13, 2010). "20 Years of Public Enemy's 'Fear Of A Black Planet'". Billboard. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Eustice, Kyle (February 17, 2011). "Public Persona". Westword. Denver. p. 39. Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r McLeod, Kembrew; DiCola, Peter (April 19, 2011). "Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling". PopMatters. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Fear of a Black Planet (Media notes). Public Enemy. Columbia Records. 1990.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Myrie 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Myrie 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Croal, N'Gai (May 4, 1998). "The Rebels Without a Pause Return". Newsweek. New York. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Stacey, Ringo P. (May 20, 2008). "Public Enemy – Chuck D Interview". The Quietus. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Kingsley (December 11, 2009). "Classic Album: Public Enemy – It Takes A Nation Of Millions to Hold Us Back". Clash. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Dery 2004, p. 479.

- ^ a b c Dery, Mark (September 1990). "Public Enemy: Confrontation". Keyboard. San Bruno. pp. 81–96.

- ^ a b c d e Myrie 2008, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Fear of a Black Planet – Public Enemy". AllMusic. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ McLeod, Kembrew (May 2009). "Interview with Chuck D & Hank Shocklee of Public Enemy". Stay Free!. New York. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ McLeod, Kembrew (March 31, 2010). "How to Make a Documentary About Sampling--Legally". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Myrie 2008, p. 147.

- ^ Myrie 2008, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b King & Selzer 2008, p. 207.

- ^ Dery 2004, p. 471.

- ^ Warrell, Laura K. (June 3, 2002). "Fight the Power". Salon. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Prahlad 2006, p. 1027.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Simon (April 1990). "Public Enemy: Fear of a Black Planet". Melody Maker. London. p. 35. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Reeves 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Santoro 1995, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e Butler, Nick (January 16, 2005). "Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet (staff review)". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Sandow, Greg (April 27, 1990). "Fear of a Black Planet". Entertainment Weekly. New York. Archived from the original on January 9, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harrington, Robert (April 15, 1990). "Public Enemy's 'Black Planet': All the Rage". The Washington Post. p. g.03. Retrieved October 17, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Kot, Greg (April 15, 1990). "Rap's bad rap". Chicago Tribune. sec. 13, pp. 4–5, 24–25. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Kot, Greg (April 15, 1990). "'Fear of a Black Planet' touches universal concerns". Chicago Tribune. sec. 13, p. 5. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Bush, John. "Welcome to the Terrordome – Public Enemy". AllMusic. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Owen, Frank (March 1990). "Public Service". Spin. Vol. 5, no. 12. New York. p. 58. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2002, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Dery 2004, p. 478.

- ^ Reeves 2009, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Christgau, Robert (July 3, 1990). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Gundersen, Edna (April 12, 1990). "Fierce 'Fear' from Public Enemy". USA Today. McLean. p. 1.D. Retrieved October 17, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "The Top 200 Tracks of the 1990s: 100–51". Pitchfork. September 1, 2010. Archived from the original on September 27, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Romanowski & George-Warren 2001, p. 789.

- ^ Sason, David (November 27, 2010). "'Fear of a Black Planet' 20 Year Anniversary". Metro Silicon Valley. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ NAIES 1992, p. 55.

- ^ Myrie 2008, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Myrie 2008, p. 124.

- ^ a b Myrie 2008, p. 123.

- ^ Pilgrim, David (March 2006). "Question of the Month: Elvis Presley and Racism". Jim Crow Museum at Feris State University. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "A note of hope from voices of experience: Correction". The Washington Post. December 3, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Myrie 2008, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Moon, Tom (April 10, 1990). "'Fear Of A Black Planet' – Concept Rap From Public Enemy". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Leland, John (September 1989). "Do the Right Thing". Spin. Vol. 5, no. 6. New York. pp. 68–74. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Gueraseva 2005, p. 187.

- ^ Lommel 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Lommel 2007, p. 51.

- ^ a b Lommel 2007, p. 52.

- ^ "In the Summer of 1989 "Fight the Power" Saved Public Enemy & Almost Sank 'Do the Right Thing'". Okayplayer. 11 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ Strong 2004, p. 1226.

- ^ "Billboard 200". Billboard. April 28, 1990. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ "Public Enemy". Official Charts Company. Albums. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Top Albums/CDs". RPM. Vol. 52, no. 4. June 9, 1990. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs". RPM. Vol. 53, no. 3. December 1, 1990. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (July 8, 1990). "A+ for Chuck D. Public Enemy is a textbook for race relations". Chicago Tribune. p. 8. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Fear of a Black Planet – Public Enemy". Billboard. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Myrie 2008, p. 133.

- ^ Hunt, Dennis (April 27, 1990). "Hammer Heads for the Top". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Light, Alan (May 17, 1990). "Public Enemy: Fear Of A Black Planet". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (May 17, 1990). "The New Guard: Pop music". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Corcoran, Michael (December 28, 1990). "Aragon books a potent pair: Public Enemy, Sonic Youth". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 11. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Kelly, Danny (April 14, 1990). "Planet Sweet". NME. London. p. 32. Archived from the original on March 11, 2000. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Bradley, Lloyd (May 1990). "Public Enemy: Fear of a Black Planet". Q. No. 44. London.

- ^ Larkin 1998, p. 4357.

- ^ a b Jones IV, James T. (December 20, 1990). "MAINSTREAM RAP; Cutting-edge sound tops pop in a year of controversy; Video's child take beat to new streets". USA Today. McLean. p. 01.A. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Pazz & Jop 1990: Critics Poll". The Village Voice. New York. March 5, 1991. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (March 5, 1991). "Pazz & Jop 1990: Dean's List". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Top Ten Records of 1990". The Boston Globe. December 20, 1990. p. 17. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "BEST & WORST 1990; POP: Rock 'n' roll got hammered, but its life and energy haven't died". USA Today. McLean. December 24, 1990. p. 04.D. Retrieved October 17, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (December 23, 1990). "POP MUSIC: A Year of Confession and Rage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Readers Make Some Surprising Choices". The State. Columbia. January 11, 1991. p. 12D. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "A List of Nominations For the 33d Annual Grammy Awards". The Philadelphia Inquirer. January 11, 1991. p. D08. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (October 22, 1991). "Chuck D All Over the Map". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c Reeves 2009, p. 86.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (January 16, 1990). "Jesus, Jews, and the Jackass Theory". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Reeves 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Hoffberger, Chase (July 25, 2008). "Public Enemy: Fear of a Black Planet, and Apocalypse 91 ... The Enemy Strikes Black (Def Jam)". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Christgau 2000, p. 255.

- ^ Wazir, Burhan (July 21, 1995). "Public Enemy: Yo! Bum Rush the Show / It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back / Fear of a Black Planet / Apocalypse 91.... The Enemy Strikes Black / Greatest Misses (Island/Def Jam)". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Public Enemy: Fear of a Black Planet". NME. London. July 15, 1995. p. 47.

- ^ Jenkins, Craig (November 25, 2014). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back / Fear of a Black Planet". Pitchfork. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy: Fear of a Black Planet". Q. No. 108. London. September 1995. p. 132.

- ^ Relic 2004, pp. 661–662.

- ^ Dyson 1995, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Dale, Jon (February 2015). "Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back / Fear of a Black Planet". Uncut. No. 213. London. pp. 89–91.

- ^ McLeod 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Alim, Ibrahim & Pennycook 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Ross 2010, p. 60.

- ^ "100 Best Albums Ever". The Guardian. London. September 19, 1997.

- ^ "100 Best Rap Albums". The Source. No. 100. New York. January 1998.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 205. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Allen, Jamie (November 9, 2000). "Music critic Christgau delivers new guide to consumers". CNN.com. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "Essential Recordings of the 90's". Rolling Stone. No. 812. New York. May 13, 1999. p. 70.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums: Fear of a Black Planet – Public Enemy". Rolling Stone. New York. November 2003. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (July 2005). "100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005". Spin. Vol. 21, no. 7. New York. p. 78. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. November 17, 2003. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Cannady, Sheryl (April 5, 2005). "Librarian Names 50 Recordings to the 2004 Registry – The Library Today (Library of Congress)". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". NME. London: IPC Media. October 26, 2013. p. 62. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Public Enemy | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Public Enemy Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Public Enemy Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1990". Billboard. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums – Year-End 1990". Billboard. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ "Public Enemy – Fight The Power". Hung Medien / hitparade.ch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Public Enemy". Official Charts Company. Singles. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Fight the Power – Public Enemy". Billboard. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Fear of a Black Planet – Public Enemy: Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy – Welcome To The Terror Dome". Hung Medien / hitparade.ch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Welcome to the Terrordome – Public Enemy". Billboard. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Public Enemy – 911 Is A Joke". Hung Medien / hitparade.ch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Whitburn 2003, p. 885.

- ^ "911 Is a Joke – Public Enemy". Billboard. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Public Enemy – Brothers Gonna Work It Out". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ a b "Brothers Gonna Work It Out – Public Enemy". Billboard. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Public Enemy – Can't Do Nuttin' For Ya Man". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Billboard R&B Charts Get Updated Names". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 50. New York. December 11, 1999. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Music Canada. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "British album certifications – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "American album certifications – Public Enemy – Fear of a Black Planet". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alim, H. Samy; Ibrahim, Awad; Pennycook, Alastair (2009). Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8058-6283-6.

- Christgau, Robert (2000). Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-24560-2.

- Dery, Mark (2004). "Public Enemy: Confrontation". In Forman, Murray; Neal, Mark Anthony (eds.). That's the Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96919-0.

- Dyson, Michael Eric (1995). "Public Enemy". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Gueraseva, Stacy (2005). Def Jam, Inc. : Russell Simmons, Rick Rubin, and the Extraordinary Story of the World's Most Influential Hip-Hop Label. One World. ISBN 0-345-46804-X.

- Jenkins, Sacha (2002). Ego Trip's Big Book of Racism. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-098896-7.

- King, Lovalerie; Selzer, Linda F., eds. (2008). New Essays on the African American Novel: From Hurston and Ellison to Morrison and Whitehead. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-60327-1.

- Larkin, Colin, ed. (1998). Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 6 (3rd ed.). Muze UK. ISBN 033374134X.

- Lommel, Cookie (2007). Russell Simmons (Hip-Hop Stars). Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-9467-9.

- McLeod, Kembrew (2007). Freedom of Expression®: Resistance and Repression in the Age of Intellectual Property. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5031-6.

- Myrie, Russell (2008). Don't Rhyme for the Sake of Riddlin': The Authorized Story of Public Enemy. Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84767-182-0.

- National Association of Interdisciplinary Ethnic Studies, National Association for Ethnic Studies (1992). Explorations in Ethnic Studies. Vol. 15–16. NAIES.

- Prahlad, Anand, ed. (2006). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Folklore: G-P. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313330379.

- Reeves, Marcus (2009). Somebody Scream!: Rap Music's Rise to Prominence in the Aftershock of Black Power. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-86547-997-5.

- Relic, Peter (2004). "Public Enemy". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Romanowski, Patricia; George-Warren, Holly, eds. (2001). The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (3rd ed.). Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 0-7432-0120-5.

- Ross, Alex (2010). Listen to This. Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-731906-0.

- Santoro, Gene (1995). Dancing in Your Head: Jazz, Blues, Rock, and Beyond. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510123-2.

- Strong, Martin Charles (October 21, 2004). The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). Canongate U.S. ISBN 1841956155.

- Whitburn, Joel (2003). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955–2002 (10th ed.). Record Research. ISBN 0898201551.

Further reading

[edit]- Draper, Jason (2008). A Brief History of Album Covers. London: Flame Tree Publishing. pp. 290–291. ISBN 9781847862112. OCLC 227198538.

- DeRogatis, Jim (August 25, 2002). "The Great Albums: Public Enemy, 'Fear of A Black Planet'". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Pareles, Jon (December 16, 1990). "'Radical' Rap: Of Pride and Prejudice". The New York Times.

- Stubbs, David (April 12, 2010). "20 Years On: Remembering Public Enemy's Fear Of A Black Planet". The Quietus.

External links

[edit]- Fear of a Black Planet at Discogs (list of releases)