Gender pay gap in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Income in the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

|

The gender pay gap in the United States is a measure comparing the earnings of men and women in the workforce. The average female annual earnings is around 80% of the average male's. When variables such as hours worked, occupations chosen, and education and job experience are controlled for, the gap diminishes with females earning 95% as much as males.[1][2][3] The exact figure varies because different organizations use different methodologies to calculate the gap. The gap varies depending on industry and is influenced by factors such as race and age. The causes of the gender pay gap are debated, but popular explanations include the "motherhood penalty," hours worked, occupation chosen, willingness to negotiate salary, and gender bias.

Statistics

[edit]

The Census Bureau tracks yearly earnings, which includes bonuses. The Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks weekly earnings, which does not include bonuses.[5] In 1980, women earned 60.2 percent of what men earned. In 1990, 71.6 percent. In 2000, 73.7. In 2009, 77.0.[6] In 2018, 81.1.[7] In 2022, Pew Research concluded that the unadjusted gap has been essentially static for 20 years among the overall workforce at around 20-22%, though it has narrowed somewhat amongst younger workers.[8][9] Pew also found that as of the end of 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic did not appear to have widened the gap.[10]

By state

[edit]

In 2016, women's earnings were lower than men's earnings in all states and the District of Columbia according to a survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.[11] The national female-to-male earnings ratio was 81.9%. Utah ranked lowest at 69.9% and Vermont ranked highest at 90.2%.[11]

By industry and occupation

[edit]

In 2003, the pay differences in many occupations were tracked. Women's median average weekly earnings, as a percent of men's, were higher in two occupations. They were "Packers and packagers, hand", at 101.4 percent, and "Health diagnosing and treating practitioner support technicians", at 100.5.[12]

In 2009, when looking at thirteen industries, the lowest was "financial activities", at 70.6 percent. The highest was "construction", at 92.2.[13][14] When looking at one hundred eight specific occupations within those industries, the lowest were "physicians and surgeons" (64.2 percent), "securities, commodities and financial services sales agents" (64.5), "financial managers" (66.6), and "other business operations specialists" (66.9). Women earned more than men in four occupations. From lowest to highest, they were "other life, physical, and social science technicians" (102.4 percent), "bakers" (104.0), "teacher assistants" (104.6), and "dining room and cafeteria attendants and bartender helpers" (111.1).[4][15]

Also in 2009 Bloomberg News reported that the sixteen women heading companies in the Standard & Poor's 500 Index averaged earnings of $14.2 million in their latest fiscal years, 43 percent more than the male average. Bloomberg News also found that of the people who were S&P 500 CEOs in 2008, women got a 19 percent raise in 2009 while men took a 5 percent cut.[16]

Several studies of women in the legal profession reveal persistent gaps in partnership numbers at major American Law Firms. Despite the fact that women have graduated from law schools in equal numbers for over twenty years, only 16–19% of law firm partners are women.[17][18]

On August 26, 2016 USA Today cited a Forbes report that the Hollywood gender pay gap is wider than that for average working women and that it is worse for stars who are older women.[19]

According to the American Association of University Professors 2018–19 faculty compensation survey, women full-time faculty were paid on average 81.6% of men and these differences are primarily due to men being in disproportionately at higher paying institutions and having higher ranks.[20]

According to a 2020 study by technology job search marketplace Hired, the gender pay gap might be increasing in tech work due to differences in expectations when negotiating salaries.[21]

By education

[edit]

While greater education increases women's overall earnings, education does not close the gender pay gap.[23] Women earn less than men at all educational levels and the gender pay gap widens for persons with advanced degrees compared to people with high school education.[24] In 2006, female high school graduates earned 69 percent of what their male counterparts earned ($29,410 for women, $42,466 for men), but women's earnings dropped to 66 percent of men's for those with advanced bachelor's degrees or more ($59,052 for women, $88,843 for men).[22]

By age

[edit]

The earnings difference between women and men varies with age, with younger women more closely approaching pay equity than older women.[26]

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that, in 2013, female full-time workers had median weekly earnings of $706, compared to men's median weekly earnings of $860. Women aged 35 years and older earned 74% to 80% of the earnings of their male counterparts. Among younger workers, the earning differences between women and men were smaller, with women aged 16 to 24 earning 88.3% of men's earnings in the same age group ($423 and $479, respectively).[27]

According to Andrew Beveridge, a professor of sociology at Queens College, between 2000 and 2005, young women in their twenties earned more than their male counterparts in some large urban centers, including Dallas (120%), New York (117%), Chicago, Boston, and Minneapolis. A major reason for this is that women have been graduating from college in larger numbers than men, and that many of those women seem to be gravitating toward major urban areas. In 2005, 53% of women in their 20s working in New York were college graduates, compared with only 38% of men of that age. Nationwide, the wages of that group of women averaged 89% of the average full-time pay for men between 2000 and 2005.[28]

According to an analysis of Census Bureau data released by Reach Advisors in 2008, single childless women between ages 22 and 30 were earning more than their male counterparts in most United States cities, with incomes that were 8% greater than males on average. This shift is driven by the growing ranks of women who attend colleges and move on to high-earning jobs.[29][30][31][32]

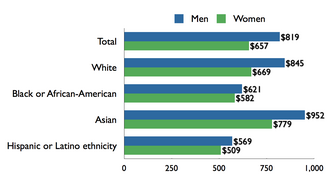

By race

[edit]In the U.S., using median hourly earnings statistics (not controlling for job type differences), disparities in pay relative to white men are largest for Latina women (58% of white men's hourly earnings and 90% of Latino men's hourly earnings) and second-largest for Black women (65% and 91% when compared to Black men), while white women have a pay gap of 82%. However, Asian women earn 87% as much as white men, making them the group of women with the smallest pay gap relative to white men.[33]

The average woman is expected to earn $430,480 less than the average white man over a lifetime. Native American women can expect to earn $883,040 less, Black women earn $877,480 less, and Latina women earn $1,007,080 less over a lifetime. Asian American women's lifetime pay deficit is $365,440.[34]

Explaining the gender pay gap

[edit]Any given raw wage gap can be dissected into an explained part, due to differences in characteristics such as education, hours worked, work experience, and occupation, and/or an unexplained part, which is typically attributed to discrimination,[35] differences not controlled for, individual choices, or a greater value placed on fringe benefits.[36] This may be further explained when America takes into account that men are more likely to negotiate for higher pay. According to a study by Carnegie Mellon, when negotiating pay, 83% of men negotiated for a higher wage compared to the 58% of women who asked for more.[37] Researchers say that women who do request either a raise or a higher starting salary are more likely than men to be penalized for those actions.[38] Cornell University economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn stated that while the overall size of the wage gap has decreased somewhat over time, the proportion of the gap that is unexplained by human capital variables is increasing.[39]

Using Current Population Survey (CPS) data for 1979 and 1995 and controlling for education, experience, personal characteristics, parental status, city and region, occupation, industry, government employment, and part-time status, Yale University economics professor Joseph G. Altonji and the United States Secretary of Commerce Rebecca Blank found that only about 27% of the gender wage gap in each year is explained by differences in such characteristics.[40]

A 1993 study of graduates of the University of Michigan Law School between 1972 and 1975 examined the gender wage gap while matching men and women for possible explanatory factors such as occupation, age, experience, education, time in the workforce, childcare, average hours worked, grades while in college, and other factors. After accounting for all that, women were paid 81.5% of what men "with similar demographic characteristics, family situations, work hours, and work experience" were paid.[41]

Similarly, a comprehensive study by the staff of the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the gender wage gap can only be partially explained by human capital factors and "work patterns." The GAO study, released in 2003, was based on data from 1983 through 2000 from a representative sample of Americans between the ages of 25 and 65. The researchers controlled for "work patterns", including years of work experience, education, and hours of work per year, as well as differences in industry, occupation, race, marital status, and job tenure. With controls for these variables in place, the data showed that women earned, on average, 20% less than men during the entire period 1983 to 2000. In a subsequent study, GAO found that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Labor "should better monitor their performance in enforcing anti-discrimination laws."[42][43][44]

Using CPS data, U.S. Bureau of Labor economist Stephanie Boraas and College of William & Mary economics professor William R. Rodgers III report that only 39% of the gender pay gap is explained in 1999, controlling for percent female, schooling, experience, region, Metropolitan Statistical Area size, minority status, part-time employment, marital status, union, government employment, and industry.[45]

Using data from longitudinal studies conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, researchers Judy Goldberg Dey and Catherine Hill analyzed some 9,000 college graduates from 1992 to 1993 and more than 10,000 from 1999 to 2000. The researchers controlled for a multitude of variables, including: occupation, industry, hours worked per week, workplace flexibility, ability to telecommute, whether employee worked multiple jobs, months at employer, marital status, whether employee had children, and whether employee volunteered in the past year. The study found that wage inequities start early and worsen over time. "The portion of the pay gap that remains unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is 5 percent one year after graduation and 12 percent 10 years after graduation. These unexplained gaps are evidence of discrimination, which remains a serious problem for women in the work force."[46][47][48]

In a 1997 study, economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn took a set of human capital variables such as education, labor market experience, and race into account and additionally controlled for occupation, industry, and unionism. While the gender wage gap was considerably smaller when all variables were taken into account, a substantial portion of the pay gap (12%) remained unexplained.[49]

A study by John McDowell, Larry Singell and James Ziliak investigated faculty promotion on the economics profession and found that, controlling for quality of PhD training, publishing productivity, major field of specialization, current placement in a distinguished department, age and post-PhD experience, female economists were still significantly less likely to be promoted from assistant to associate and from associate to full professor—although there was also some evidence that women's promotion opportunities from associate to full professor improved in the 1980s.[50]

Economist June O'Neill, former director of the Congressional Budget Office, found an unexplained pay gap of 8% after controlling for experience, education, and number of years on the job. Furthermore, O'Neill found that among young people who have never had a child, women's earnings approach 98 percent of men's.[51]

In a stance rejecting discrimination, a 2009 study for the Department of Labour by the CONSAD Research Corporation concluded, "it is not possible now, and doubtless will never be possible, to determine reliably whether any portion of the observed gender wage gap is not attributable to factors that compensate women and men differently on socially acceptable bases, and hence can confidently be attributed to overt discrimination against women." and continued "In addition, at a practical level, the complex combination of factors that collectively determine the wages paid to different individuals makes the formulation of policy that will reliably redress any overt discrimination that does exist a task that is, at least, daunting and, more likely, unachievable." The conclusion was based largely on a study by Eric Solberg & Teresa Laughlin (1995), who found that "occupational selection is the primary determinant of the gender wage gap" (as opposed to discrimination) because "any measure of earnings that excludes fringe benefits may produce misleading results as to the existence magnitude, consequence, and source of market discrimination." They found that the average wage rate of females was only 87.4% of the average wage rate of males; whereas, when earnings were measured by their index of total compensation (including fringe benefits), the average value of the index for females was 96.4% of the average value for males.[52]

A 2010 study by Catalyst, a nonprofit that works to expand opportunities for women in business, of male and female MBA graduates found that after controlling for career aspirations, parental status, years of experience, industry, and other variables, male graduates are more likely to be assigned jobs of higher rank and responsibility and earn, on average, $4,600 more than women in their first post-MBA jobs. This affects women's ability to pay off student loan debt since college isn't cheaper for a woman even though she can expect to make less after she earns a degree than her male peers. This results in women being in disproportionately more debt than men. This extra debt makes having less income even more debilitating as women have a harder time paying off student loan debt.[53][54][55][56][57]

A 2014 study found that the gender pay gap in the United States decreased in size significantly from 1970 to 2010, mainly because the unexplained portion of the gap decreased significantly during this period.[58]

In 2018, economists at the University of Chicago and Stanford University, working with Uber analyzing the gender pay gap of Uber drivers demonstrated an average 7% pay gap in a context where gender discrimination was not possible and pay was not negotiated, showing the difference entirely explainable as the difference in average productivity between men and women as a result of driving styles (the average man drove faster), experience (the mean male had more experience driving with Uber than the mean female), and driver choices (men on average worked hours and locations with higher returns).[59][60] The factors above explained 50%, 30%, and 20% of the variance respectively.

Sources of disparity

[edit]The extent to which discrimination plays a role in explaining gender wage disparities can be difficult to quantify, due to a number of potentially confounding variables. A 2010 research review by the majority staff of the United States Congress Joint Economic Committee reported that studies have consistently found unexplained pay differences even after controlling for measurable factors that are assumed to influence earnings – suggestive of unknown/unmeasurable contributing factors of which gender discrimination may be one.[61] Other studies have found direct evidence of discrimination – for example, more jobs went to women when the applicant's sex was unknown during the hiring process than when it was known.[61] Other factors that have been speculated to contribute to the gap include a greater value placed on non-wage benefits and a difference in willingness and/or skills to negotiate salaries.[36][62][63]

Hours worked

[edit]A report in 2014 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics stated that employed men worked 52 minutes more than employed women on the days they worked and that this difference partly reflects women's greater likelihood of working part-time.[64][65] In the book Biology at Work: Rethinking Sexual Equality, Browne writes: "Because of the sex differences in hours worked, the hourly earnings gap [...] is a better indicator of the sexual disparity in earnings than the annual figure. Even the hourly earnings ratio does not completely capture the effects of sex differences in hours, however, because employees who work more hours also tend to earn more per hour."[66]

However, numerous studies indicate that variables such as hours worked account for only part of the gender pay gap and that the pay gap shrinks but does not disappear after controlling for many human capital variables known to affect pay.[40][41][43][46][49] Moreover, Gary Becker argued in a 1985 article that the traditional division of labor in the family disadvantages women in the labor market as women devote substantially more time and effort to housework and have less time and effort available for performing market work.[67] The OECD (2002) found that women work fewer hours because in the present circumstances the "responsibilities for child-rearing and other unpaid household work are still unequally shared among partners."[68]

By taking into account education, work experience, and "soft variables" such as motivation and cultural norms there seems to be one major variable that sticks out when talking about the wage gap, and that is the time-off women take for family affairs. In the article Human Capital Models and the Gender Pay Gap, Olson brings up the point that although there's argument that women are paid less than men because of their time-off away from work for family reasons, such as child-rearing, and unpaid house chores actually does not have an effect on women's salaries later in their career. Since this time off does not show a significance difference, there should not be a reason for the wage gap, unless it is based on gender.[69][failed verification]

Occupational segregation

[edit]

Occupational segregation refers to the way that some jobs (such as truck driver) are dominated by men, and other jobs (such as child care worker) are dominated by women. Considerable research suggests that predominantly female occupations pay less, even controlling for individual and workplace characteristics.[70] Economists Blau and Kahn stated that women's pay compared to men's had improved because of a decrease in occupational segregation. They also argued that the gender wage difference will decline modestly and that the extent of discrimination against women in the labor market seems to be decreasing.[71]

In 2008, a group of researchers examined occupational segregation and its implications for the salaries assigned to male- and female-typed jobs. They investigated whether participants would assign different pay to 3 types of jobs wherein the actual responsibilities and duties carried out by men and women were the same, but the job was situated in either a traditionally masculine or traditionally feminine domain. The researchers found statistically significant pay differentials between jobs defined as "male" and "female," which suggest that gender-based discrimination, arising from occupational stereotyping and the devaluation of the work typically done by women, influences salary allocation. The results fit with contemporary theorizing about gender-based discrimination.[72][73]

In 1996, a study showed that if a white woman in an otherwise all-male workplace moved to an all-female workplace, she would lose 7% of her wages. If a black woman did the same thing, she would lose 19% of her wages.[74] Another study from the same year calculated that if female-dominated jobs did not pay lower wages, women's median hourly pay nationwide would go up 13.2% (men's pay would go up 1.1%, due to raises for men working in "women's jobs").[75]

Numerous studies indicate that the pay gap shrinks but does not disappear after controlling for occupation and a host of other human capital variables.[40][41][43][46][49]

Workplace flexibility

[edit]It has been suggested that women choose less-paying occupations because they provide flexibility to better manage work and family. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin has made this case in reviews of the literature in 2014 and 2016.[76][77]

A 2009 study of high school valedictorians in the U.S. found that female valedictorians were planning to have careers that had a median salary of $74,608, whereas male valedictorians were planning to have careers with a median salary of $97,734. As to why the females were less likely than the males to choose high paying careers such as surgeon and engineer, the New York Times article quoted the researcher as saying, "The typical reason is that they are worried about combining family and career one day in the future."[78]

However, studies in 1990 by Jerry A. Jacobs and Ronnie Steinberg, as well as Jennifer Glass separately, found that male-dominated jobs actually have more flexibility and autonomy than female-dominated jobs, thus allowing a person, for example, to more easily leave work to tend to a sick child.[79][80] Similarly, Heather Boushey stated that men actually have more access to workplace flexibility and that it is a "myth that women choose less-paying occupations because they provide flexibility to better manage work and family."[81]

Based on data from the 1980s, economists Blau and Kahn and Wood et al. separately argue that "free choice" factors, while significant, have been shown in studies to leave large portions of the gender earnings gap unexplained.[41][49]

Gender stereotypes

[edit]Research suggests that gender stereotypes may be the driving force behind occupational segregation because they influence men and women's educational and career decisions.

Studies by Michael Conway et al., David Wagner and Joseph Berger, John Williams and Deborah Best, and Susan Fiske et al. found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women at most things, as well as specific assumptions that men are better at some particular tasks (e.g., math, mechanical tasks) while women are better at others (e.g., nurturing tasks).[82][83][84][85] Shelley Correll, Michael Lovaglia, Margaret Shih et al., and Claude Steele show that these gender status beliefs affect the assessments people make of their own competence at career-relevant tasks.[86][87][88] Correll found that specific stereotypes (e.g., women have lower mathematical ability) affect women's and men's perceptions of their abilities (e.g., in math and science) such that men assess their own task ability higher than women performing at the same level. These "biased self-assessments" shape men and women's educational and career decisions.[89][90]

Similarly, the OECD states that women's labour market behaviour "is influenced by learned cultural and social values that may be thought to discriminate against women (and sometimes against men) by stereotyping certain work and life styles as 'male' or 'female'." Further, the OECD argues that women's educational choices "may be dictated, at least in part, by their expectations that [certain] types of employment opportunities are not available to them, as well as by gender stereotypes that are prevalent in society."[68]

Direct discrimination

[edit]Economist David Neumark argued that discrimination by employers tends to steer women into lower-paying occupations and men into higher-paying occupations.[91]

Bias favoring gender roles

[edit]Several authors suggest that members of low-status groups are subject to negative stereotypes and attributes concerning their work-related competences.[92][93] Similarly, studies suggest that members of high-status groups are more likely to receive favorable evaluations about their competence, normality, and legitimacy.[94][95][96]

David R. Hekman and colleagues found that men receive significantly higher customer satisfaction scores than equally well-performing women. Customers who viewed videos featuring a female and a male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer were 19% more satisfied with the male employee's performance and also were more satisfied with the store's cleanliness and appearance although the actors performed identically, read the same script, and were in exactly the same location with identical camera angles and lighting. In a second study, they found that male doctors were rated as more approachable and competent than equally well performing female doctors.[97] They interpret their findings to suggest that customer ratings tend to be inconsistent with objective indicators of performance and should not be uncritically used to determine pay and promotion opportunities. They contend that customer biases have potential adverse effects on female employees' careers.[98][99][100][101][102]

Similarly, a study (2000) conducted by economic experts Claudia Goldin from Harvard University and Cecilia Rouse from Princeton University shows that when evaluators of applicants could see the applicant's gender they were more likely to select men. When the applicants gender could not be observed, the number of women hired significantly increased.[103][104] David Neumark, a professor of economics at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues (1996) found statistically significant evidence of sex discrimination against women in hiring. In an audit study, matched pairs of male and female pseudo-job seekers were given identical résumés and sent to apply for jobs as waiters and waitresses at the same set of restaurants. In high priced restaurants, a female applicant's probability of getting an interview was 35 percentage points lower than a male's and her probability of getting a job offer was 40 percentage points lower. Additional evidence suggests that customer biases in favor of men partly underlie the hiring discrimination. According to Neumark, these hiring patterns appear to have implications for sex differences in earnings, as informal survey evidence indicates that earnings are higher in high-price restaurants.[91]

A 2007 study showed a substantial bias against women with children.[105]

Barriers in science

[edit]In 2006, the United States National Academy of Sciences found that women in science and engineering are hindered by bias and "outmoded institutional structures" in academia. The report Beyond Bias and Barriers says that extensive previous research showed a pattern of unconscious but pervasive bias, "arbitrary and subjective" evaluation processes and a work environment in which "anyone lacking the work and family support traditionally provided by a 'wife' is at a serious disadvantage."[106] Similarly, a 1999 report on faculty at MIT finds evidence of differential treatment of senior women and points out that it may encompass not simply differences in salary but also in space, awards, resources and responses to outside offers, "with women receiving less despite professional accomplishments equal to those of their male colleagues."[107]

Research finds that work by men is often subjectively seen as higher-quality than objectively equal or better work by women compared to how an actual scientific review panel measured scientific competence when deciding on research grants. The results showed that women scientists needed to be at least twice as accomplished as their male counterparts to receive equal credit[108] and that among grant applicants men have statistically significant greater odds of receiving grants than equally qualified women.[109] In contrast, a 2018 audit study substituted common names of black men, white men, black women and white women on grant proposals and found no evidence of bias by scientific reviewers.[110]

A 2019 study found that even when blinded to the gender of the applicant, applications written by males were more likely to be funded.[111]

According to the American Association of University Professors 2018–19 faculty compensation survey, women full-time faculty were paid on average 81.6% of men and these differences are primarily due to men being in disproportionately at higher paying institutions and having higher ranks.[20]

A study by Wendy M. Williams and Stephen J. Ceci found that female applicants were strongly favored over men in an experiment designed to assess bias in hiring for professors in biology, engineering, economics and psychology.[112] However, this studies results have been met with skepticism from other researchers, since it contradicts other studies on the issue. Joan C. Williams, a distinguished professor at the University of California's Hastings College of Law, raised issues with its methodology, pointing out that the fictional female candidates it used were unusually well-qualified.[113] In contrast, Ernesto Reuben, an assistant professor of management at Columbia University said Williams' and Ceci's study is methodologically sound and Wendy Williams noted that faculty short lists are always made up of superb candidates.[114] A different study in 2012 found subtle biases in favor of the hypothetical male candidate when both candidates were undergraduates applying for a paid lab manager position. Both male and female faculty favored the male candidate to a similar degree.[115]

Anti-female bias and perceived role incongruency

[edit]Research on competence judgments has shown a pervasive tendency to devalue women's work and, in particular, prejudice against women in male-dominated roles which are presumably incongruent for women.[116] Organizational research that investigates biases in perceptions of equivalent male and female competence has confirmed that women who enter high-status, male-dominated work settings often are evaluated more harshly and met with more hostility than equally qualified men.[117][118] The "think manager – think male" phenomenon[119] reflects gender stereotypes and status beliefs that associate greater status worthiness and competence with men than women.[120] Gender status beliefs shape men's and women's assertiveness, the attention and evaluation their performances receive, and the ability attributed to them on the basis of performance.[120] They also "evoke a gender-differentiated double standard for attributing performance to ability, which differentially biases the way men and women assess their own competence at tasks that are career relevant, controlling for actual ability."[121]

Alice H. Eagly and Steven J. Karau (2002) argue that "perceived incongruity between the female gender role and leadership roles leads to two forms of prejudice: (a) perceiving women less favorably than men as potential occupants of leadership roles and (b) evaluating behavior that fulfills the prescriptions of a leader role less favorably when it is enacted by a woman. One consequence is that attitudes are less positive toward female than male leaders and potential leaders. Other consequences are that it is more difficult for women to become leaders and to achieve success in leadership roles."[122] Moreover, research suggests that when women are acknowledged to have been successful, they are less liked and more personally derogated than equivalently successful men.[123] Assertive women who display masculine, agentic traits are viewed as violating prescriptions of feminine niceness and are penalized for violating the status order.[124]

However, a 2018 study analyzing the pay gap of Uber drivers showed the existence of a 7% gender disparity in hourly wages in a context where gender discrimination was impossible at the employer level (contracts and algorithms were gender blind) and where there was no evidence of discrimination at the rider level.[59]

Maternity leave

[edit]The economic risk and resulting costs of a woman possibly leaving jobs for a period of time or indefinitely to nurse a baby is cited by many to be a reason why women are less common in the higher paying occupations such as CEO positions and upper management.[citation needed] It is much easier for a man to be hired in these higher prestige jobs than to risk losing a female job holder. In a survey conducted of about 500 managers in the Slater &Gordon law firm, more than 40% of the managers agreed they generally hesitate to hire woman who fall in the age group of potentially bearing children or woman who already have children.[125] Thomas Sowell argued in his 1984 book Civil Rights that most of pay gap is based on marital status, not a "glass ceiling" discrimination. Earnings for men and women of the same basic description (education, jobs, hours worked, marital status) were essentially equal. That result would not be predicted under explanatory theories of "sexism".[126] However, it can be seen as a symptom of the unequal contributions made by each partner to child raising. Cathy Young cites men's and fathers' rights activists who contend that women do not allow men to take on paternal and domestic responsibilities.[127]

Many Western countries have some form of paternity leave to attempt to level the playing field in this regard. However, even in relatively gender-equal countries like Sweden, where parents are given 16 months of paid parental leave irrespective of gender, fathers take on average only 20% of the 16 months of paid parental and choose to transfer their days to their partner.[128][129] In addition to maternity leave, Walter Block and Walter E. Williams have argued that marriage in and of itself, not maternity leave, in general will leave females with more household labor than the males.[citation needed] The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that married women earn 75.5% as much as married men while women who have never married earn 94.2% of their unmarried male counterparts' earnings.[130]

One study estimated that 10% of the convergence of the gender gap in the 1980s and 30% in the 1990s can be accounted for by the increasing availability of contraceptives.[131]

Motherhood penalty and men's marriage premium

[edit]Several studies found a significant motherhood penalty on wages and evaluations of workplace performance and competence even after statistically controlling for education, work experience, race, whether an individual works full- or part-time, and a broad range of other human capital and occupational variables.[132][133][134] The OECD confirmed the existing literature, in which "a significant impact of children on women's pay is generally found in the United Kingdom and the United States."[68] However, one study found a wage premium for women with very young children.[135]

Stanford University professor Shelley Correll and colleagues (2007) sent out more than 1,200 fictitious résumés to employers in a large Northeastern city, and found that female applicants with children were significantly less likely to get hired and if hired would be paid a lower salary than male applicants with children. This despite the fact that the qualification, workplace performances and other relevant characteristics of the fictitious job applicants were held constant and only their parental status varied. Mothers were penalized on a host of measures, including perceived competence and recommended starting salary. Men were not penalized for, and sometimes benefited from, being a parent. In a subsequent audit study, Correll et al. found that actual employers discriminate against mothers when making evaluations that affect hiring, promotion, and salary decisions, but not against fathers.[136][137][138][139][140] The researchers review results from other studies and argue that the motherhood role exists in tension with the cultural understandings of the "ideal worker" role and this leads evaluators to expect mothers to be less competent and less committed to their job.[141][142] Fathers do not experience these types of workplace disadvantages as understandings of what it means to be a good father are not seen as incompatible with understandings of what it means to be a good worker.[143]

Similarly, Fuegen et al. found that when evaluators rated fictitious applicants for an attorney position, female applicants with children were held to a higher standard than female applicants without children. Fathers were actually held to a significantly lower standard than male non-parents.[144] Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick show that describing a consultant as a mother leads evaluators to rate her as less competent than when she is described as not having children.[145]

Research has also shown there to be a "marriage premium" for men with labor economists frequently reporting that married men earn higher wages than unmarried men, and speculating that this may be attributable to one or more of the following causes: (1) more productive men marry at greater rates (attributing the marriage premium to selection bias), (2) men become more productive following marriage (possibly due to labor market specialization by men and domestic specialization by women), (3) employers favor married men, or (4) married men feel a responsibility ethic to maximize income.[146][147][148]

Lincoln (2008) found no support for the specialization hypothesis among full-time employed workers.[135] One study found that among identical twins with one married and the other single, average wage increased 26%.[149] Some studies have suggested this premium is pronounced in the working lives of men after becoming fathers. The "fatherhood premium" is the increase in pay specifically after men becoming fathers. Fathers can expect their salaries to be boosted by 4 to 7% beyond that of their childless male counterparts.[150][151] The fatherhood premium varies by race, as white father receive larger dividends than do fathers of color.[152] Some studies have suggested this premium is greater for men with children while others have shown fatherhood to have no effect on wages one way or the other.[135][153][154][155][156] Boosts to fathers' salaries and decreases in mothers' are the result of two intersecting factors. First, parenthood allows and/or prompts men to invest more time in work, while women are prompted to invest less. Second, employers' beliefs of the productivity and worth of employees are influenced by gender, as fathers are seen as more productive, while mothers are viewed as less committed to work and thus less valuable.[157][151][158]

Gender differences in perceived pay entitlement

[edit]According to Serge Desmarais and James Curtis, the "gender gap in pay …is related to gender differences in perceptions of pay entitlement."[159] Similarly, Major et al. argue that gender differences in pay expectations play a role in perpetuating non-performance related pay differences between women and men.[160]

Perceptions of wage entitlement differ between women and men such that men are more likely to feel worthy of higher pay[161][162][163][164][165][166][167] while women's sense of wage entitlement is depressed.[168][169] Women's beliefs about their relatively lower worth and their depressed wage entitlement reflects their lower social status such that when women's status is raised, their wage entitlement raises as well.[168][170] However, gender-related status manipulation has no impact on men's elevated wage entitlement. Even when men's status is lowered on a specific task (e.g., by telling them that women typically outperform men on this task), men do not reduce their self-pay and respond with elevated projections of their own competence.[171] The usual pattern whereby men assign themselves more pay than women for comparable work might explain why men tend to initiate negotiations more than women.[172]

In a study by psychologist Melissa Williams et al., published in 2010, study participants were given pairs of male and female first names, and asked to estimate their salaries. Men and to a lesser degree women estimated significantly higher salaries for men than women, replicating a similar but more general finding in adolescents.[173][174] In a subsequent study, participants were placed in the role of employer and were asked to judge what newly hired men and women deserve to earn. The researchers found that men and to a lesser extent women assign higher salaries to men than women based on automatic stereotypic associations. The researchers argue that observations of men as higher earners than women has led to a stereotype that associates men (more than women) with wealth, and that this stereotype itself may serve to perpetuate the wage gap at both conscious and nonconscious levels. For example, a male-wealth stereotype may influence an employer's initial salary offer to a male job candidate, or a female college graduate's intuitive sense about what salary she can appropriately ask for at her first job.[173]

Negotiating salaries

[edit]Some studies of simulated salary negotiations have found that men on average negotiated more aggressively than women.[175][176] Other studies, however, have found no gender difference in pay negotiations.[177] A 1991 study investigating the salary negotiating behaviors and starting salary outcomes of graduating MBA students and found that women did not negotiate less than men, but women did obtain lower monetary returns from negotiation—which could have large impacts over the course of a career.[178]

Situational factors which are assumed to influence salary negotiation include:

- Knowledge of the competitive rate of pay for a task.[179][180]

- Consciousness of gender stereotypes about negotiation.[181]

Small et al. suggest that "framing situations as opportunities for negotiation is particularly intimidating to women, as this language is inconsistent with norms for politeness among low-power individuals, such as women". Their study of pay negotiations found that women were less likely than men to negotiate when the behavior was labeled as "negotiating" but equally likely when the behavior was labeled as "asking".[182]

Riley and Babcock found that women are penalized when they try to negotiate starting salaries. Male evaluators tended to rule against women who negotiated but were less likely to penalize men; female evaluators tended to penalize both men and women who negotiated, and preferred applicants who did not ask for more. The study also showed that women who applied for jobs were not as likely to be hired by male managers if they tried to ask for more money, while men who asked for a higher salary were not negatively affected.[183][184][185][186]

However, a 2018 study analyzing the pay gap of Uber drivers showed that men earned 7% more than women in a context where salaries were not negotiated.[59]

Danger wage premium

[edit]The Bureau of Labor Statistics investigated job traits that are associated with wage premiums, and stated: "The duties most highly valued by the marketplace are generally cognitive or supervisory in nature. Job attributes relating to interpersonal relationships do not seem to affect wages, nor do the attributes of physically demanding or dangerous jobs."[187] Economists Peter Dorman and Paul Hagstrom (1998) state that "The theoretical case for wage compensation for risk is plausible but hardly certain. If workers have utility functions in which the expected likelihood and cost of occupational hazards enter as arguments, if they are fully informed of risks, if firms possess sufficient information on worker expectations and preferences (directly or through revealed preferences), if safety is costly to provide and not a public good, and if risk is fully transacted in anonymous, perfectly competitive labor markets, then workers will receive wage premia that exactly offset the disutility of assuming greater risk of injury or death. Of course, none of these assumptions applies in full and if one or more of them is sufficiently at variance with the real world, actual compensation may be less than utility-offsetting, nonexistent, or even negative – a combination of low pay and poor working conditions."[188]

Impact

[edit]Economy

[edit]An October 2012 study by the American Association of University Women found that over the course of a 35-year career, an American woman with a college degree will make about $1.2 million less than a man with the same education, or a woman would earn 83 cents for every dollar a man made. The consequences of the pay gap include lower lifetime pay for women, less income for families, and higher rates of poverty across the United States.[189] If women receive more benefits equivalent to men, the poverty rate for working women would decrease. Therefore, closing the pay gap by raising women's wages would have a stimulus effect that would grow the U.S. economy by at least 3% to 4%.[190] Women currently make up 70 percent of Medicaid recipients and 80 percent of welfare recipients, meaning their lower incomes make them more eligible for government and state funded programs. Increasing women's workplace participation from its present rate of 76% to 84%, as it is in Sweden, the U.S. could add 5.1 million women to the workforce, again, 3% to 4% of the size of the U.S. economy.[191]

Pensions

[edit]According to a report by the United States Congress Joint Economic Committee, the gender pay gap jeopardizes women's retirement security. Of the multiple sources of income Americans rely on later in life, many are directly linked to a worker's earnings over his or her career. According to research, women have about 30% less saved by the time they retire.[192] The Center for American Progress found that by the end of a woman's career, a full-time working woman will have lost out on $417,400 of income.[192] Social Security benefits, based on lifetime earnings, and defined benefit pension distributions that are typically calculated using a formula based on a worker's tenure and salary during peak-earnings years. The persistent gender pay gap leaves women with less income from these sources than men. For example, older women's Social Security benefits are 71% of older men's benefits ($11,057 for women versus $15,557 for men in 2009). Incomes from public and private pensions based on women's own work were just 60% and 48% of men's pension incomes, respectively.[193]

Legal regulation

[edit]Federal laws

[edit]The federal Equal Pay Act of 1963 made it illegal to pay women less simply based on gender. The Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made all sex discrimination in covered workplaces illegal (with exceptions), and this coverage was expanded to the basis of pregnancy by the 1978 Pregnancy Discrimination Act.[citation needed]

In 2009, President Barack Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. This law extended the statute of limitations on cases where a worker found that they were receiving discriminatory pay, allowing them to sue and receive recompense more than six months after they received the pay. This was seen as a victory for those fighting against the gender wage gap, because if a woman at the end of her career found that she had been making less money than men who were doing the same work, she now had more than six months from the date of her last pay check to file a claim and possibly receive the wages that were denied.

State laws

[edit]In June 2017, Governor Kate Brown signed into law the Oregon Equal Pay Act, which forbids employers from using job seekers' prior salaries in hiring decisions.[194]

In Colorado, the Equal Pay for Equal Work Act took effect on January 1, 2021, with several provisions:[195][196]

- Allows workers to file a civil lawsuit to enforce the law

- Has similar requirements for equal work to the federal 1963 law

- Prohibits employers from asking about or considering pay history

- Prohibits employers from preventing discussions between employees about pay

- Requires employers to advertise promotion opportunities to all employers

- Requires employers to advertise a pay range and benefits with job descriptions

- Requires employers to maintain records for use in later enforcement actions

Popular culture reactions

[edit]

To help raise awareness on the pay gap, a pop-up store named "76 is Less Than 100" operated during the month of April 2015 in the Garfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh. The nonprofit store, which sells arts and crafts designed by women, charges men full price while women get a 24% discount to reflect the pay gap between men and women in Pennsylvania.[197][198] The store made national headlines in the wake of Patricia Arquette referencing the pay gap at the 87th Academy Awards two months before.[199] In November 2015 the operators opened a second iteration in New Orleans, titled "66<100" to reflect the pay gap in Louisiana.[200]

Public figure reactions

[edit]Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, is a strong advocate of closing the gender pay gap. In her book, Lean In, she urges professional women to "lean in" to their careers, negotiate for higher salaries to decrease the pay gap, and to find supportive partners who will actively help raise children to help lessen the motherhood penalty.[201] She is also the founder of LeanIn.Org, which has run national social media campaigns using the hashtags #BanBossy and #LeanInTogether.

Oscar-winning American actress Jennifer Lawrence has also brought international attention to the gender pay gap with an essay in fellow pay gap advocate Lena Dunham's Lenny Letter. In her essay, she addresses the fact that she was paid less than her American Hustle co-stars, which was made public by the Sony hacking scandal. She largely blamed herself for having "failed as a negotiator" and being focused on being liked. The essay highlighted that the gender pay gap exists for every industry and all across Hollywood.[202]

Author and advocate Christine Michel Carter has also spoke out against the gender pay gap, specifically Black Women's Equal Pay Day, stating the path to racial and gender equity in the workplace will involve “radical action.”[203] In her Forbes column, she addresses the fact that Black women face disproportionately high barriers in the workplace and questions the solutions recommended to close the gender pay gap.[204]

See also

[edit]- US labor law

- Equal pay for women

- Glass ceiling

- Income inequality in the United States

- Pregnancy discrimination in the United States

- Equal Pay Day

- Gender pay gap in the United States tech industry

Legislation:

References

[edit]- ^ Gurchiek, Kathy (April 2, 2019). "Study: Global Gender Pay Gap Has Narrowed but Still Exists". SHRM. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap (Spring 2017 ed.). Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ O'Brien, Sara Ashley (April 13, 2015). "78 cents on the dollar: The facts about the gender wage gap". CNNMoney. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Highlights of Women's Earnings in 2009. Report 1025, June 2010.

- ^ "Women in the Labor Force, A Databook" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics. US Dept of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ DeNavas-Walt, Carmen; Proctor, Bernadette D.; Smith, Jessica C. (2010). "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-238, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. pp. 7, 50.

- ^ "Women had higher median earnings than men in relatively few occupations in 2018". The Economics Daily. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Aragão, Carolina. "Gender pay gap in U.S. hasn't changed much in two decades". Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Greenwood, Shannon (March 1, 2023). "The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap". Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Fry, Richard. "Some gender disparities widened in the U.S. workforce during the pandemic". Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ a b "Highlights of women's earnings in 2016" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. August 2017. pp. 53–55.

- ^ "Highlights in Women's Earnings in 2003" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics, Report 978. September 2004.

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics. Women's earnings and employment by industry, 2009. Chart data, February 16, 2011.

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics. Women's earnings and employment by industry, 2009. TED article, February 16, 2011.

- ^ Ariane Hegewisch, Claudia Williams, and Amber Henderson. The Gender Wage Gap by Occupation. Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Institute for Women's Policy Research, April 2011.

- ^ Bloomberg. Women CEOs Earn More Than Men, Get Pay Raise in 2009. Retrieved on September 7, 2010.

- ^ Williams, Joan C.; Richardson, Veta (2011). "New Millennium, Same Glass Ceiling? The Impact of Law Firm Compensation Systems on Women". Hastings Law Journal. 62: 597.

- ^ Peterson, Trond; Morgan, Laurie (September 1995). "Separate and Unequal: Occupation-Establishment Sex Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap". American Journal of Sociology. 101 (2): 329–65. doi:10.1086/230727. JSTOR 2782431. S2CID 145707764.

- ^ Puente, Maria (August 25, 2016). "Why men make more than women in Hollywood". USA Today.

- ^ a b "2018–19 Faculty Compensation Survey Results | AAUP". www.aaup.org.

- ^ Carson, Erin (March 31, 2020). "It's Equal Pay Day, but the gender pay gap could be widening in tech". CNET.

"Salary expectations any candidate has for a given job are closely tied to the salary ultimately offered to them by a prospective employer," Hired CEO Mehul Patel said in the report. "Our data reveals male candidates expect to earn more and our report shows their offers match that expectation." The idea is that 65% of the time, women will ask for lower salaries than men when applying for the same job at the same company.

- ^ a b "The 2009 Statistical Abstract: Income, Expenditures, Poverty, and Wealth" (PDF). US Census Bureau. 2009. p. 449. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- ^ Blau, Francine D.; Kahn, Lawrence K. (2007). "The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?" (PDF). Academy of Management Perspectives. 21 (1): 7–23. doi:10.5465/amp.2007.24286161. S2CID 152531847. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ AAUW Report: The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap

- ^ "Women's earnings as a percentage of men's, 1979–2005 : The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ Catalyst. Women's Earnings and Income. Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine April 2011.

- ^ "Highlights of women's earnings in 2013" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Report 1051. December 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Sam. For Young Earners in Big City, a Gap in Women's Favor. The New York Times, August 3, 2007.

- ^ Dougherty, Conor. Young Women's Pay Exceeds Male Peers. The Walls Street Journal, September 1, 2010.

- ^ Luscombe, Belinda. Workplace Salaries: At Last, Women on Top TIME, September 1, 2010.

- ^ Sharockman, Aaron. What pay gap? Young women out-earn men in cities, conservative pundit claims PolitiFact, April 9, 2014.

- ^ Zarya, Valentina. Why Women in Their Early 20s Are Out-Earning Men Fortune, April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Racial, gender wage gaps persist in U.S. despite some progress". Pew Research Center. July 1, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ^ Reporter, Lydia O'Connor; Post, The Huffington (April 12, 2016). "The Wage Gap: Terrible For All Women, Even Worse For Women Of Color". The Huffington Post. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ^ Eagly, A.H., & Carli, L. L. Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4221-1691-3.

- ^ a b "An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women" (PDF). US Department of Labor; CONSAD Research Corp. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ Vedantam, Shankar (July 30, 2007). "Salary, Gender and the Social Cost of Haggling". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Carmichael, Sarah Green (February 26, 2015). "Why "Network More" Is Bad Advice for Women". Harvard Business Review.

- ^ Blau, Francine D; Kahn, Lawrence M (2007). "The Gender Pay Gap". The Economists' Voice. 4 (4). doi:10.2202/1553-3832.1190. S2CID 201102126..

- ^ a b c Altonji, Joseph G.; Blank, Rebecca M. (1999). "Race and gender in the labor market". In Ashenfelter, Orley C.; Card, David (eds.). Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol. 3. pp. 3143–259. doi:10.1016/S1573-4463(99)30039-0. ISBN 978-0-444-50189-9.

- ^ a b c d Wood, Robert G.; Corcoran, Mary E.; Courant, Paul (1993). "Pay Differences Among the Highly Paid: the Male-Female Earnings Gap in Lawyers' Salaries" (PDF). Journal of Labor Economics. 11 (3): 417–41. doi:10.1086/298302. S2CID 153581021. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ GAO. Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws. GAO-08-799, August 11, 2008.

- ^ a b c About.com. Why Women Still Make Less than Men. Archived January 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on July 23, 2011.

- ^ Folbre, Nancy. "Happy Equal Pay Day." The New York Times, April 28, 2009.

- ^ Boraas, Stephanie; Rodgers, William M. (2003). "How does gender play a role in the earnings gap? An update" (PDF). Monthly Labor Review. 126 (3): 9–15.

- ^ a b c Carman, Diane. "Why do men earn more? Just because." Denver Post, April 24, 2007.

- ^ Arnst, Cathy. Women and the pay gap. Archived September 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Bloomberg Businessweek, April 27, 2007.

- ^ American Management Association. Bridging the Gender Pay Gap. October 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Blau, Francine D.; Kahn, Lawrence M. (January 1997). "Swimming Upstream: Trends in the Gender Wage Differential in the 1980s". Journal of Labor Economics. 15 (1): 1–42. doi:10.1086/209845. JSTOR 2535313. S2CID 154658290. SSRN 10786.

- ^ McDowell, John M; Singell, Larry D; Ziliak, James P (1999). "Cracks in the Glass Ceiling: Gender and Promotion in the Economics Profession". American Economic Review. 89 (2): 392–96. doi:10.1257/aer.89.2.392. JSTOR 117142.

- ^ O'Neill, June; O'Neill, Dave (2005). What Do Wage Differentials Tell Us about Labor Market Discrimination?. National Bureau of Economic Research (Report). doi:10.3386/w11240. SSRN 697165.

- ^ "Gender Wage Gap Final Report Archived October 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, 2009

- ^ Stark, Betsy. "The Myth of the Pipeline: Inequality Still Plagues Working Women, Study Finds." ABC News, February 18, 2010.

- ^ Wolgemuth, Liz. "Why Some Women Skirt the Wage Gap." U.S. News, May 14, 2010.

- ^ Ludden, Jennifer. "Despite New Law, Gender Salary Gap Persists." National Public Radio, April 19, 2010.

- ^ Lavelle, Louis. "Catalyst: Women MBAs Lag Behind Men in Jobs, Pay, Promotions." Bloomberg Businessweek, March 3, 2010.

- ^ Carter, Nancy M. & Christine Silver (2010). Pipeline's broken promise. Catalyst.

- ^ Mandel, Hadas; Semyonov, Moshe (October 1, 2014). "Gender Pay Gap and Employment Sector: Sources of Earnings Disparities in the United States, 1970–2010". Demography. 51 (5): 1597–1618. doi:10.1007/s13524-014-0320-y. ISSN 0070-3370. PMID 25149647. S2CID 207472327.

- ^ a b c Cook, Cody; Diamond, Rebecca; Hall, Jonathan V.; List, John A.; Oyer, Paul (May 2020). "The Gender Earnings Gap in the Gig Economy: Evidence from over a Million Rideshare Drivers" (PDF). web.stanford.edu.

- ^ "Female Uber drivers earn $1.24 per hour less than men: Study". February 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "Invest in Women, Invest in America: A Comprehensive Review of Women in the U.S. Economy". Washington, DC: United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. December 2010. p. 80.

- ^ Jackson, Brooks (June 22, 2012). "Obama's 77-Cent Exaggeration". FactCheck.org.

- ^ Graduating to a Pay Gap – The Earnings of Women and Men One Year after College Graduation (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2019

- ^ "American Time Use Survey". Bureau of Labor Statistics. June 24, 2015.

- ^ U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Women in the Labor Force: A Databook, December 2014 Report 1052 (accessed May 24, 2019)

- ^ Browne, Kingsley R. (2002). Biology at Work: Rethinking Sexual Equality. Rutgers University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-8135-3053-6.

- ^ Becker, Gary S. (January 1985). "Human Capital, Effort, and the Sexual Division of Labor". Journal of Labor Economics. 3 (1): S33–58. doi:10.1086/298075. JSTOR 2534997. S2CID 153445351.

- ^ a b c "Women at work: who are they and how are they faring?" (PDF). Employment Outlook. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2002. pp. 61–125. ISBN 978-92-64-19778-7.

- ^ Olson, Josephine E. (September 15, 2012). "Human Capital Models and the Gender Pay Gap". Sex Roles. 68 (3–4): 186–197. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0208-5. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 144582371.

- ^ Blau, Francine D; Kahn, Lawrence M (2000). "Gender Differences in Pay". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (4): 75–99. doi:10.1257/jep.14.4.75.

- ^ Cicarelli, James and Julianne Cicarelli. Distinguished women economists. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003, pp. 36–40, ISBN 978-0-313-30331-9.

- ^ Alksnis, Christine; Desmarais, Serge; Curtis, James (2008). "Workforce Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap: Is 'Women's' Work Valued as Highly as 'Men's'?". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 38 (6): 1416–41. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00354.x.

- ^ Vedantam, Shankar. "The Wage Gap – Unconscious Bias in Judging the Value of Predominantly 'Female' Professions." Psychology Today, February 18, 2010.

- ^ England, Paula; Reid, Lori L.; Kilbourne, Barbara Stanek (1996). "The Effect of the Sex Composition of Jobs on Starting wages in an Organization: Findings from the NLSY". Demography. 33 (4): 511–21. doi:10.2307/2061784. JSTOR 2061784. PMID 8939422. S2CID 24596884.

- ^ Figart, Deborah M.; Lapidus, June (1996). "The Impact of Comparable Worth on Earnings Inequality". Work and Occupations. 23 (3): 297–318. doi:10.1177/0730888496023003004. S2CID 153936753.

- ^ "The True Story of the Gender Pay Gap - Freakonomics". Freakonomics. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Goldin, Claudia (2014). "A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter". American Economic Review. 104 (4): 1091–1119. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.708.4375. doi:10.1257/aer.104.4.1091. ISSN 0002-8282. S2CID 155044380.

- ^ Steinberg, Jacques (June 1, 2009). "Do the Ambitions of High School Valedictorians Differ by Gender?". New York Times.

- ^ Glass, Jennifer (1990). "The Impact of Occupational Segregation on Working Conditions". Social Forces. 68 (3): 779–96. doi:10.1093/sf/68.3.779. JSTOR 2579353.

- ^ Jacobs, Jerry A.; Steinberg, Ronnie J. (1990). "Compensating Differentials and the Male-Female Wage Gap: Evidence from the New York State Comparable Worth Study". Social Forces. 69 (2): 439–68. doi:10.1093/sf/69.2.439. JSTOR 2579667.

- ^ Boushey, Heather (April 24, 2007). "Strengthening the Middle Class: Ensuring Equal Pay for Women". Center for Economic and Policy Research. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Conway, Michael; Pizzamiglio, M. Teresa; Mount, Lauren (1996). "Status, communality, and agency: Implications for stereotypes of gender and other groups". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 71 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.25. PMID 8709000.

- ^ Wagner, David G.; Berger, Joseph (1997). "Gender and Interpersonal Task Behaviors: Status Expectation Accounts". Sociological Perspectives. 40 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/1389491. JSTOR 1389491. S2CID 147319093.

- ^ Williams, John E.; Best, Deborah L. (1990). Measuring Sex Stereotypes: A Multinational Study. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.[page needed]

- ^ Fiske, Susan T.; Cuddy, Amy J. C.; Glick, Peter; Xu, Jun (2002). "A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 82 (6): 878–902. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.320.4001. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878. PMID 12051578. S2CID 17057403.

- ^ Lovaglia, Michael J.; Lucas, Jeffrey W.; Houser, Jeffrey A.; Thye, Shane R.; Markovsky, Barry (1998). "Status Processes and Mental Ability Test Scores". American Journal of Sociology. 104 (1): 195–228. doi:10.1086/210006. S2CID 54043625.

- ^ Shih, Margaret; Pittinsky, Todd L.; Ambady, Nalini (1999). "Stereotype Susceptibility: Identity Salience and Shifts in Quantitative Performance". Psychological Science. 10: 80–83. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00111. S2CID 3852881.

- ^ Steele, Claude M. (1997). "A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance". American Psychologist. 52 (6): 613–29. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.9608. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613. PMID 9174398. S2CID 19952.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2001). "Gender and the Career Choice Process: The Role of Biased Self-Assessments". American Journal of Sociology. 106 (6): 1691–730. doi:10.1086/321299. S2CID 142863258.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2004). "Constraints into Preferences: Gender, Status, and Emerging Career Aspirations". American Sociological Review. 69 (1): 93–113. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.520.8370. doi:10.1177/000312240406900106. JSTOR 3593076. S2CID 8735336.

- ^ a b Neumark, David; Bank, Roy J.; Van Nort, Kyle D. (1996). "Sex Discrimination in Restaurant Hiring: An Audit Study" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 111 (3): 915–41. doi:10.2307/2946676. JSTOR 2946676. S2CID 150106209.

- ^ Fernandez, John P. Racism and sexism in corporate life. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1981, ISBN 978-0-669-04477-5.[page needed]

- ^ O'Leary, Virginia E.; Ickovics, Jeanette R. (1992). "Cracking the glass ceiling: overcoming isolation and alienation". In Sekaran, U.; Leong, F. T. L. (eds.). Womanpower: Managing in times of demographic turbulence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. pp. 7–30. ISBN 978-0-8039-4106-9.

- ^ Aquino, Karl; Bommer, William H. (2003). "Preferential Mistreatment: How Victim Status Moderates the Relationship Between Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Workplace Victimization". Organization Science. 14 (4): 374–85. doi:10.1287/orsc.14.4.374.17489.

- ^ Giannopoulos, Constantina; Conway, Michael; Mendelson, Morris (2005). "The Gender of Status: The Laypersons' Perception of Status Groups is Gender-Typed". Sex Roles. 53 (11–12): 795–806. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-8293-3. S2CID 144373141.

- ^ Sidanius, Jim & Felicia Pratto. Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-521-62290-5.[page needed]

- ^ "In patient satisfaction scores, what role does bias play?". American Medical Association. September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas. "A Customer Bias in Favor of White Men." New York Times, June 23, 2009.

- ^ Vedantam, Shankar. "Caveat for Employers." Washington Post, June 1, 2009.

- ^ Jackson, Derrick. "Subtle, and stubborn, race bias." Boston Globe, July 6, 2009.

- ^ National Public Radio, Lake Effect Archived October 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hekman, David R.; Aquino, Karl; Owens, Bradley P.; Mitchell, Terence R.; Schilpzand, Pauline; Leavitt, Keith (2010). "An Examination of Whether and How Racial and Gender Biases Influence Customer Satisfaction". Academy of Management Journal. 53 (2): 238–64. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2010.49388763. S2CID 28930751.

- ^ Weiner, Joann M. "No, It's Not Your Imagination; We're Biased Against Women." Politics Daily, Retrieved on July 13, 2011.

- ^ Goldin, Claudia; Rouse, Cecilia (1997). "Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of 'Blind' Auditions on Female Musicians". American Economic Review. 90 (4): 715–42. doi:10.3386/w5903. JSTOR 117305. SSRN 225685.

- ^ Shelley J. Correll; Stephen Benard; In Paik (2007). "Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty?" (PDF). American Journal of Sociology. 112 (5date=March 2007). The University of Chicago Press: 1297–1339. doi:10.1086/511799. JSTOR 10.1086/511799. S2CID 7816230.

- ^ Dean, Cornelia. "Bias Is Hurting Women in Science, Panel Reports." The New York Times, September 19, 2006.

- ^ "A Study on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT." The MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. XI, No. 4, March 1999.

- ^ Wennerås, Christine; Wold, Agnes (1997). "Nepotism and sexism in peer-review". Nature. 387 (6631): 341–43. Bibcode:1997Natur.387..341W. doi:10.1038/387341a0. PMID 9163412. S2CID 522864.

- ^ Bornmann, Lutz; Mutz, Rüdiger; Daniel, Hans-Dieter (2007). "Gender differences in grant peer review: A meta-analysis". Journal of Informetrics. 1 (3): 226–38. arXiv:math/0701537. Bibcode:2007math......1537B. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2007.03.001. S2CID 14457854.

- ^ Kaiser, Jocelyn (June 8, 2018). "No bias in NIH reviews?". Science. 360 (6393): 1055. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1055K. doi:10.1126/science.360.6393.1055. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29880666. S2CID 47006047.

- ^ Else, Holly (May 1, 2019). "Male researchers' 'vague' language more likely to win grants". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01402-4. PMID 32350421. S2CID 188050381.

- ^ Wendy M. Williams (2015). "National hiring experiments reveal 2:1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (17): 5360–5365. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5360W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418878112. PMC 4418903. PMID 25870272.

- ^ Sarah Kaplan (April 14, 2015). "Study finds, surprisingly, that women are favored for jobs in STEM". Washington Post. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ^ "Study suggests STEM faculty hiring favors women over men". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Moss-Racusin, Corinne A.; Dovidio, John F.; Brescoll, Victoria L.; Graham, Mark J.; Handelsman, Jo (October 9, 2012). "Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (41): 16474–16479. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10916474M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3478626. PMID 22988126.

- ^ Eagly, Alice H.; Makhijani, Mona G.; Klonsky, Bruce G. (1992). "Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 111 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.3. S2CID 53330130.

- ^ Collinson, David, David Knights, and Margaret Collinson. Managing to discriminate. London; New York: Routledge, 1990, ISBN 978-0-415-01817-3.[page needed]

- ^ Heilman, Madeline E. (2001). "Description and Prescription: How Gender Stereotypes Prevent Women's Ascent Up the Organizational Ladder". Journal of Social Issues. 57 (4): 657–74. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00234. S2CID 144504496.

- ^ Schein, Virginia E. (2001). "A Global Look at Psychological Barriers to Women's Progress in Management". Journal of Social Issues. 57 (4): 675–88. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00235.

- ^ a b Ridgeway, Cecilia L. (2001). "Gender, Status, and Leadership". Journal of Social Issues. 57 (4): 637–55. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00233.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2004). "Constraints into Preferences: Gender, Status, and Emerging Career Aspirations". American Sociological Review. 69 (1): 93–113. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.520.8370. doi:10.1177/000312240406900106. JSTOR 3593076. S2CID 8735336.

- ^ Eagly, Alice H.; Karau, Steven J. (2002). "Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders". Psychological Review. 109 (3): 573–98. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.315. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573. PMID 12088246. S2CID 1283792.

- ^ Heilman, Madeline E.; Wallen, Aaron S.; Fuchs, Daniella; Tamkins, Melinda M. (2004). "Penalties for Success: Reactions to Women Who Succeed at Male Gender-Typed Tasks". Journal of Applied Psychology. 89 (3): 416–27. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.416. PMID 15161402.

- ^ Rudman, Laurie A.; Glick, Peter (2001). "Prescriptive Gender Stereotypes and Backlash Toward Agentic Women". Journal of Social Issues. 57 (4): 743–62. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00239. hdl:2027.42/146421. S2CID 54219902.

- ^ "40% of managers avoid hiring younger women to get around maternity leave". the Guardian. Press Association. August 11, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Sowell, Thomas, "Civil Rights: Rhetoric or Reality", 1984 (see Chapter 5, "The Special Case of Women") and "Markets and Minorities", 1981.[page needed]

- ^ The mama lion at the gate – Salon.com Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine[full citation needed]

- ^ "Swedish dads steer clear of paternity leave". The Local Sweden. March 12, 2008.

- ^ "Swedish parental leave and gender equality: Achievements and reform challenges in a European perspective" (PDF). Arbetsrapport/Institutet för Framtidsstudier; 2005:11. 2006. ISBN 91-89655-69-9. ISSN 1652-120X. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2006.

- ^ Wolgemuth, Liz. "Young Women Closing in on Gender Wage Parity." USNews.com July 31, 2009.

- ^ Bailey, Martha J.; Hershbein, Brad; Miller, Amalia R. (2012). "The Opt-In Revolution? Contraception and the Gender Gap in Wages". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 4 (3): 225–54. doi:10.1257/app.4.3.225. PMC 3684076. PMID 23785566. SSRN 2027804.

- ^ Budig, Michelle J.; England, Paula (April 2001). "The Wage Penalty for Motherhood". American Sociological Review. 66 (2): 204–25. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.512.8060. doi:10.2307/2657415. JSTOR 2657415.

- ^ Anderson, Deborah J.; Binder, Melissa; Krause, Kate (January 2003). "The Motherhood Wage Penalty Revisited: Experience, Heterogeneity, Work Effort, and Work-Schedule Flexibility". Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 56 (2): 273–94. doi:10.2307/3590938. JSTOR 3590938. SSRN 258750.

- ^ Avellar, Sarah; Smock, Pamela J. (2003). "Has the Price of Motherhood Declined over Time? A Cross-Cohort Comparison of the Motherhood Wage Penalty". Journal of Marriage and Family. 65 (3): 597–607. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1026.4335. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00597.x. hdl:2027.42/73089. JSTOR 3600026.

- ^ a b c Lincoln, Anne E. (2008). "Gender, Productivity, and the Marital Wage Premium". Journal of Marriage and Family. 70 (3): 806–14. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00523.x. JSTOR 40056369.

- ^ Folbre, Nancy. "The Anti-Mommy Bias." New York Times, March 26, 2009.

- ^ Goodman, Ellen. "A third gender in the workplace." Boston Globe, May 11, 2007.

- ^ Cahn, Naomi and June Carbone. "Five myths about working mothers." The Washington Post, May 30, 2010.

- ^ Young, Lauren. "The Motherhood Penalty: Working Moms Face Pay Gap Vs. Childless Peers." Archived August 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Bloomsberg Businessweek, June 5, 2009.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J.; Benard, Stephen; Paik, In (2007). "Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty?". American Journal of Sociology. 112 (5): 1297–339. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.709.8363. doi:10.1086/511799. S2CID 7816230.

- "Mothers face disadvantages in getting hired, study shows". Psych Central. August 4, 2005. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014.

- ^ Blair-Loy, Mary. Competing devotions: Career and family among women executives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-674-01089-5.[page needed]

- ^ Ridgeway, Cecilia L.; Correll, Shelley J. (2004). "Unpacking the Gender System: A Theoretical Perspective on Gender Beliefs and Social Relations". Gender & Society. 18 (4): 510–31. doi:10.1177/0891243204265269. S2CID 8797797.

- ^ Townsend, Nicholas W. The package deal: Marriage, work, and fatherhood in men's lives. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-1-56639-957-9.[page needed]

- ^ Fuegen, Kathleen; Biernat, Monica; Haines, Elizabeth; Deaux, Kay (2004). "Mothers and Fathers in the Workplace: How Gender and Parental Status Influence Judgments of Job-Related Competence". Journal of Social Issues. 60 (4): 737–54. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00383.x. S2CID 142992355.

- "Mothers in the Workplace Held to Stricter Standards, Study Suggests". OSU News Research Archive (Press release). 2005. Archived from the original on March 1, 2005.

- ^ Cuddy, Amy J. C.; Fiske, Susan T.; Glick, Peter (2004). "When Professionals Become Mothers, Warmth Doesn't Cut the Ice". Journal of Social Issues. 60 (4): 701–18. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.4841. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00381.x. S2CID 6371898.

- ^ Orloff, Ann (1996). "Gender in the Welfare State". Annual Review of Sociology. 22: 51–78. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.51. JSTOR 2083424.

- ^ Gorman, Elizabeth (2000). "Marriage and money: The effect of marital status on attitudes toward pay and finances". Work and Occupations. 27: 64–88. doi:10.1177/0730888400027001004. S2CID 144918094. see also https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/inspired-life/wp/2015/04/02/dont-be-a-bachelor-why-married-men-work-harder-and-smarter-and-make-more-money

- ^ "Don't be a bachelor: Why married men work harder, smarter and make more money". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Antonovics, Kate; Town, Robert (2004). "Are all the good men married? Uncovering the sources of the marital wage premium". American Economic Review. 94 (2): 317–321. doi:10.1257/0002828041301876. S2CID 16100427.

- ^ Hodges, Melissa J.; Budig, Michelle J. (December 2010). "Who Gets the Daddy Bonus?". Gender & Society. 24 (6): 717–745. doi:10.1177/0891243210386729. ISSN 0891-2432. S2CID 145228347.

- ^ a b Lundberg, Shelly; Rose, Elaina (November 1, 2000). "Parenthood and the earnings of married men and women". Labour Economics. 7 (6): 689–710. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00020-8. ISSN 0927-5371.