Sumerian Tablets – Discovery and Decoding of Ancient Cuneiform

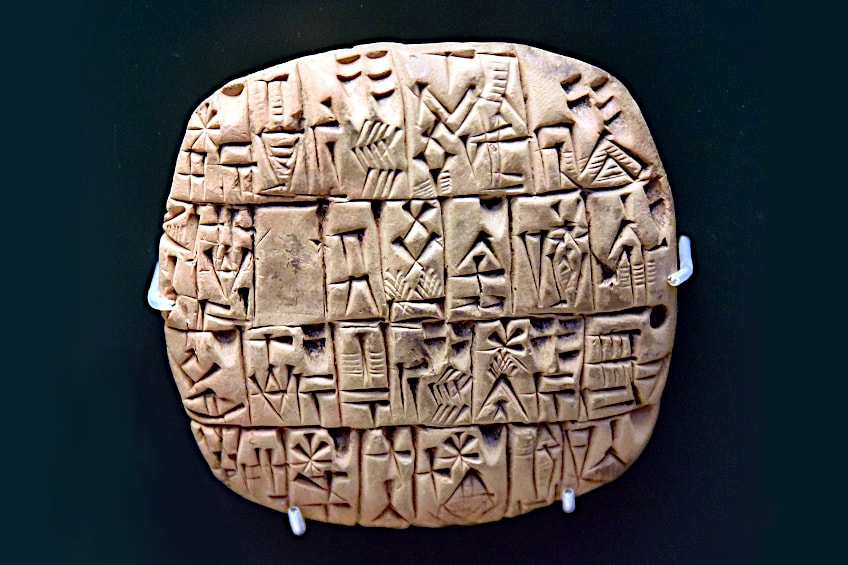

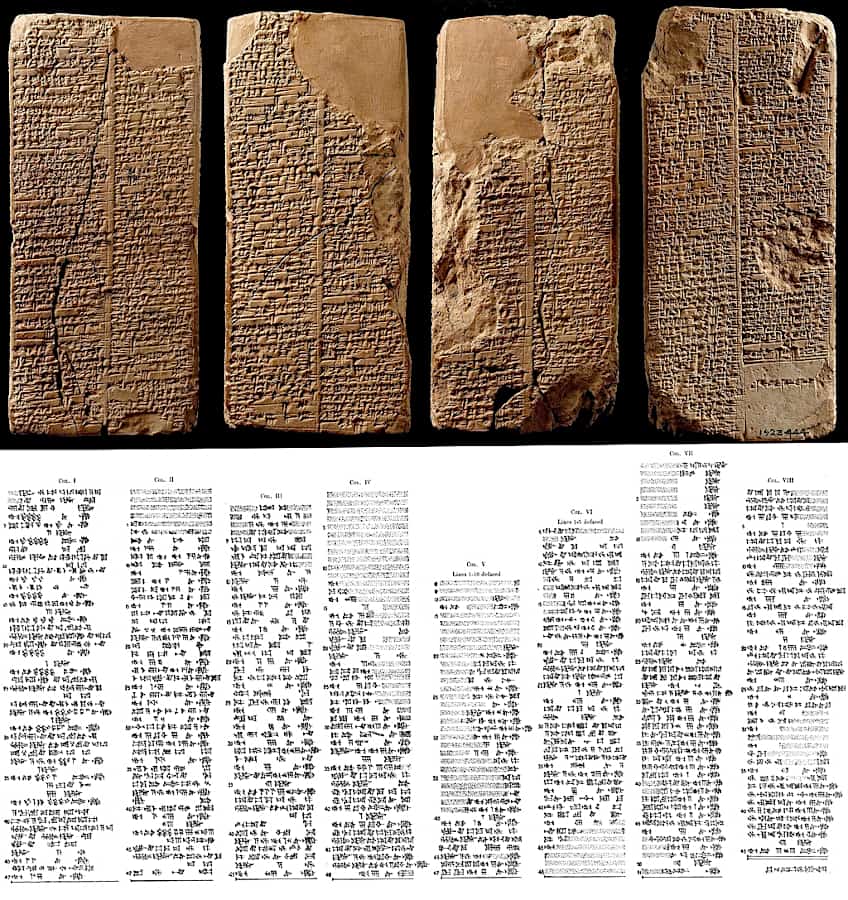

The ancient Sumerian language originated in Mesopotamia and is regarded as the oldest known written language in the world. But, what did the Sumerians write on if there was no paper at that period of human history? These ancient Sumerian texts were inscribed in the cuneiform script, on Sumerian clay tablets called Cuneiform tablets, which were eventually adopted by other Mesopotamian and nearby regional languages such as Elamite, Akkadian, and Hittite. Today, we will be examining the Sumerian tablets’ translations and history.

Understanding the Sumerian Tablets

Paper and technological gadgets are the media used for writing in the current world. Yet, the Sumerians did not discover paper and instead employed a different material for their ancient Sumerian language. The Sumerians etched documents and texts on Sumerian clay tablets, which have a longer lifespan than paper. As a result, a great number of these Sumerian tablets have survived throughout millennia and have been discovered by archaeologists. Much data could be gleaned from these Cuneiform tablets after the ancient Sumerian texts were decoded.

The ancient Sumerian language is classified as a linguistic isolate, which implies that no other language is known to be connected to it. This language initially appeared approximately 3,100 BCE in the Sumerian culture, which was situated in southern Mesopotamia.

The Sumerian language and culture flourished throughout the centuries that followed. Southern and Northern Mesopotamia were united under the Akkadians, who established the world’s first empire, in the 24th century BCE. In terms of spoken language, Akkadian progressively displaced the Sumerians’. Nonetheless, the ancient Sumerian language survived as a written language for a far longer length of time, but with significantly reduced usage. Written Akkadian died out at the start of the Christian era, while the Sumerian language died out shortly before.

The Cuneiform Tablet Script

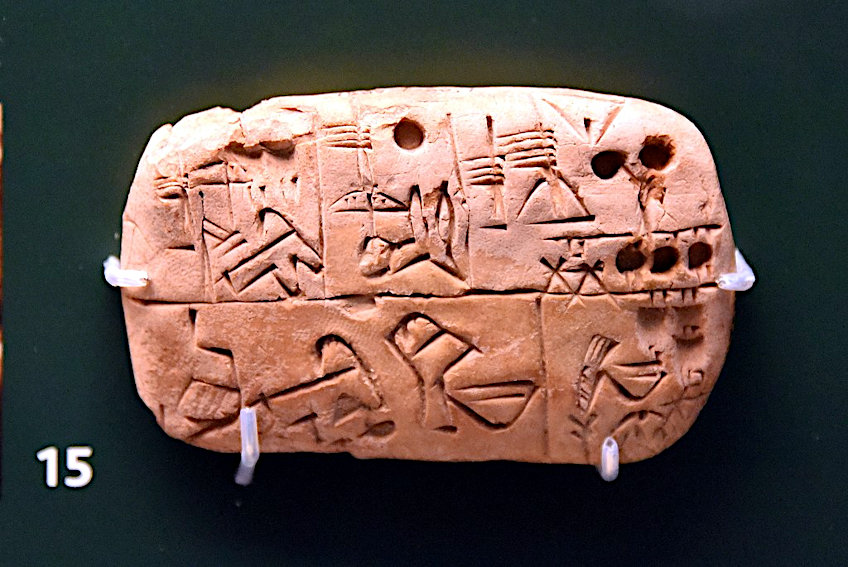

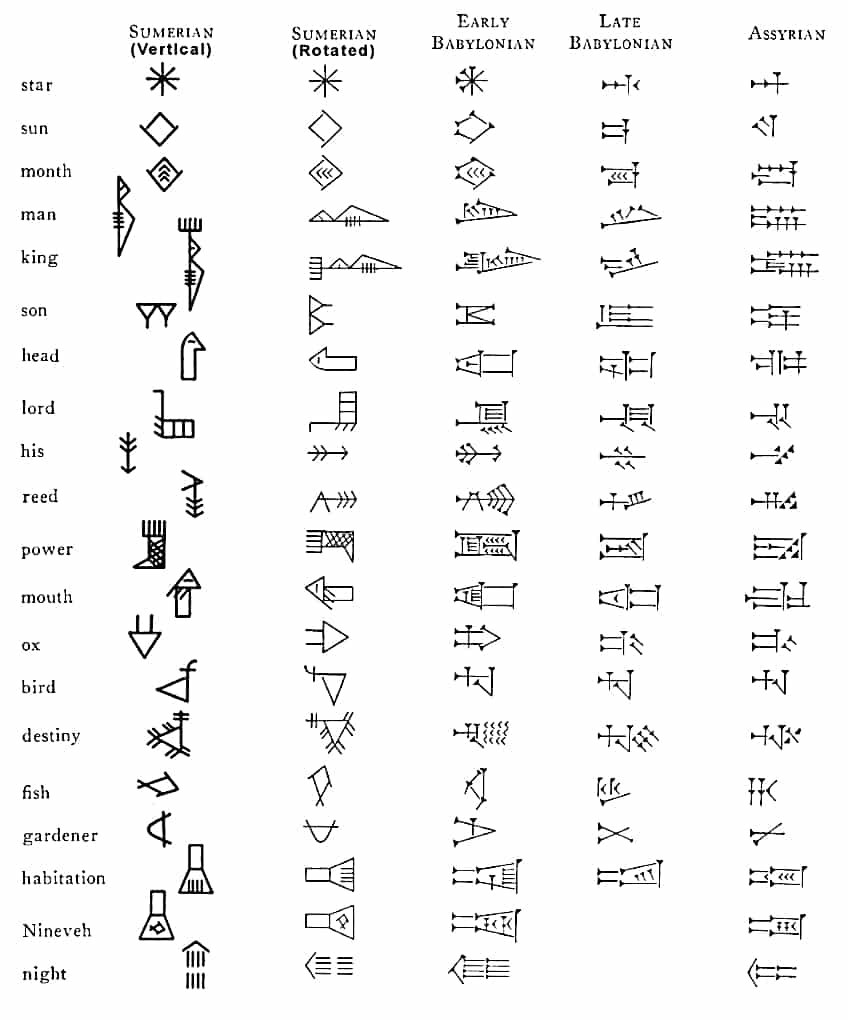

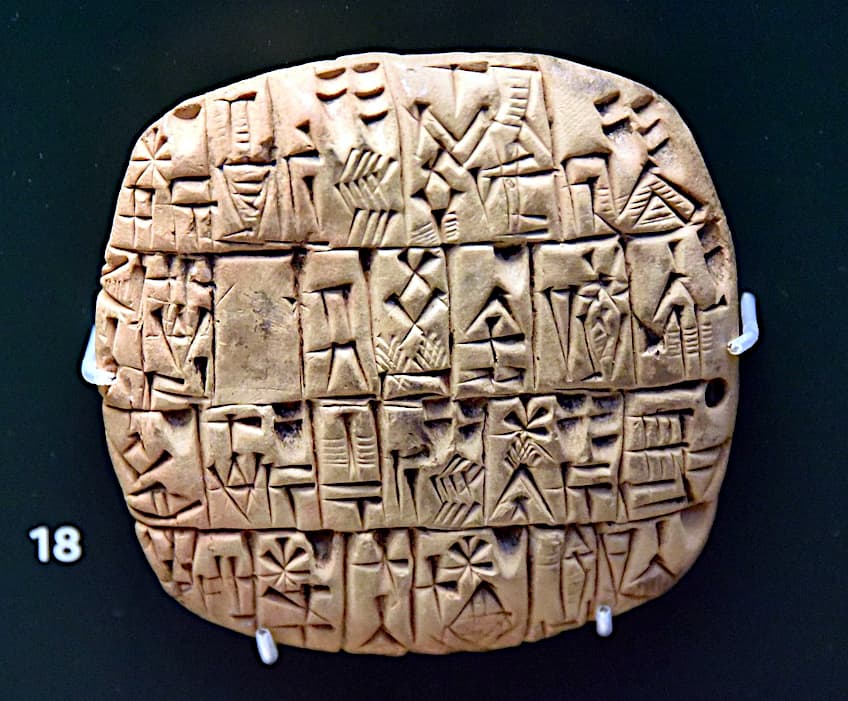

The Sumerian writing style is classified as cuneiform, which is a relatively new term dating from the early 18th century. This word comes from Middle French and Latin sources and means “wedge-shaped”. This is an accurate description of the script, which is easily identified by its wedge-shaped characters. Cuneiform tablets are said to have originated approximately 8,000 BCE for commercial purposes.

This script began as pictograms, that were employed to visually depict trade products and cattle. Small clay tokens symbolizing these items were created and enclosed in clay envelopes. A token would be placed against the clay on the envelope’s outside to reveal the contents on the inside.

With the passage of time, the Sumerians understood that they could easily substitute the tokens for writing directly into the clay. The symbols were stylized throughout time, streamlining the writing process and giving rise to cuneiform tablet script. French archeologist, Denise Schmandt-Besserat, discovered the relationship between the clay tokens and the cuneiform tablet script in the 1970s. Aside from the sorts of trade products, Sumerian traders were also concerned with keeping track of their numbers, which contributed to the creation of the cuneiform numerical system. As previously stated, the Sumerians utilized clay tokens to denote the sort of trade products. These tokens also reflected the number of items. For example, if 10 loaves of bread are logged, 10 clay tokens of this product are created. To ensure that the amount of the actual things equaled the number of the tokens, just count the tokens and the objects.

This method is known as correspondent counting, and it was employed even before the Sumerian civilization emerged, although other types of counters, like tally marks, were used instead. This approach was easy and effective, but it was time-consuming, especially when dealing with a huge number of commodities. Clay tokens were substituted with writing on clay tablets after the creation of the cuneiform alphabet, which made recording simpler.

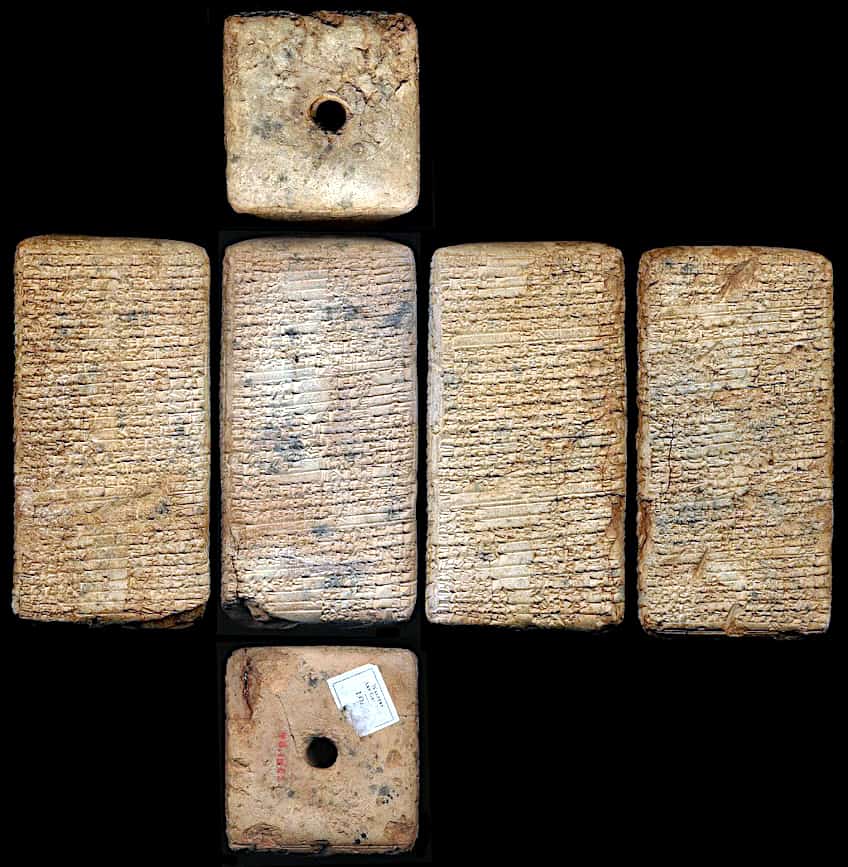

Having to draw the sign for a loaf of bread ten times to symbolize that amount was still inefficient. As a result, the Sumerians devised a number system in which product quantities were expressed by abstract symbols, significantly simplifying the recording procedure. Cuneiform writing was written on a range of surfaces, including metal, stone, and wood. The Sumerians, on the other hand, preferred the clay tablet as a medium. A scribe would inscribe the necessary letters into a block of soft clay, which was then sun-dried, using a stylus (typically manufactured of reed).

These tablets were delicate, but they could be reused by immersing them in water and creating new ones. Other tablets were baked in kilns (intentionally or accidentally when a structure burned down), making them hard and robust enough to remain in the archaeological record to be found by archaeologists.

Region of Discovery of the Sumerian Tablets

Small quantities of clay tablets were discovered at certain locations, while enormous stockpiles of the same material were discovered at others. Clay cuneiform tablets, as previously stated, were employed not just by the Sumerians, but also by other civilizations in Mesopotamia and nearby regions. As a result, some of these locations may include clay tablets written in languages other than Sumerian. Furthermore, because the Akkadian language became the region’s lingua franca during the rise of the Akkadian Empire, layers of Akkadian clay tablets have been unearthed at a number of locations. These locations include the Ashurbanipal Library, Assur, and Mari.

Ebla and Drehem are two sites where a large quantity of Sumerian tablets have been discovered. The former lies about 10 kilometers south of Nippur and has produced about 15,000 Sumerian clay tablets. Ebla, on the other hand, is in Syria, and its tablets, in both Eblaite and Sumerian, are numbered in the thousands.

Sumerian Tablets’ Translations

The ancient Sumerian language must first be translated in order to comprehend the content of these cuneiform tablets. Luckily, by the time these tablets were discovered at the two locations, in the 20th century, the ancient Sumerian language had been translated. The Sumerian tablets’ translations started in the early 19th century when researchers began to confront the colossal texts left abandoned by the Achaemenid Empire.

This empire’s language was Old Persian, which was inscribed in a variant of the cuneiform script. Once this writing was translated, academics understood that the Achaemenid writings were made up of three languages that all spoke about the same thing. As a result, after Old Persian was decoded, the other two scripts could also be examined.

Akkadian and Elamite were identified as the two additional languages. The translation of the former was a significant advancement since it served as a model for the understanding of other cuneiform languages. Scholars first assumed that Sumerian was a variant of Akkadian, and it wasn’t until the 20th century that they realized their error and acknowledged Sumerian as a distinct language. As a linguistic isolate, the Sumerian structure is unconnected to any other form of language, making translation difficult for experts.

Despite its extinction as a living language, Sumerian was nevertheless employed by the Babylonian priests. As a consequence, grammatical lists and lexicons were established, as well as many literal translations of religious writings into Babylonian.

The texts that have survived give academics a wealth of material to work with today. As mentioned before, the cuneiform tablet script evolved as a technique for tracking the transit of products. This is shown, for example, in the Drehem clay tablets, which contain statements such as “Urazagnuuna got 23 lambs, 14 sheep, 37 goats, from Nirnbati which have passed inspection”.

Other Uses of the Sumerian Tablets

Aside from the sort of transaction, the tablets also reveal the date on which it was completed, allowing historians to shed some insight into the Sumerian calendar. The employment of cuneiform writing for accounting is particularly evident in Ebla since the bulk of tablets from the site deal with royal palace spending and acquisitions. Although the cuneiform alphabet was first devised for commercial objectives, the Sumerians quickly discovered that it could also be used for other purposes.

This is arguably best expressed in the script’s rising complexity over time. When cuneiform writing was completely evolved, it could not only express items and numbers, but also a wide range of language features.

Some symbols are logograms, which represent individual words, whereas others are phonograms, which indicate spoken syllables. There were further characters that served as determiners, indicating the classification of the word. This was a complex writing system, with academics identifying over 1,000 individual characters in earlier writings and 400 in modern ones.

The Recording of Mythological Tales on the Sumerian Clay Tablets

The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2,100 BCE), considered the world’s earliest piece of literature, is one well-known narrative preserved on Sumerian cuneiform tablets. The standard form of this tale was penned in Akkadian and was found in the Library of Ashurbanipal around the mid-19th century by the Turkish Assyriologist, Hormuzd Rassam. Despite the text being unfinished, it is the most complete existing text of the epic at the moment. There is also a Sumerian version of the epic, although it is far less well-known than its Akkadian equivalent. Furthermore, it is significantly less comprehensive, consisting of only five poems. It is thought that these poems circulated individually, rather than as a coherent manuscript like the one unearthed at Nineveh.

The Epic of Gilgamesh exemplifies the relationship between the Sumerian and Akkadian languages. Although the Sumerians devised cuneiform and started to write on clay tablets, their records have been eclipsed by the Akkadians.

The Akkadians rose to prominence during the 24th century BCE under Sargon of Akkad and built the world’s first empire. Because of its supremacy, the Akkadian language evolved into a lingua franca that was utilized not just inside the empire, but also outside its boundaries. More significantly, Akkadian progressively replaced Sumerian as a communication language. Following the demise of the Akkadian Empire, the Sumerian civilization saw a brief resurgence under the Third Dynasty of Ur. Mesopotamia fell under the hands of the First Babylonian Empire with the conclusion of the Sumerian renaissance. The new rulers, like the Sumerians, adopted the cuneiform tablet. The Babylonian language, on the other hand, was a form of Akkadian, not Sumerian. The Assyrian language is also an Akkadian variation.

Nonetheless, the Sumerian clay tablets constitute a vital source of knowledge about this ancient culture. Scholars have learned not just about the structure and grammar of the ancient Sumerian language, but also about the way of life and culture of this ancient society through these Sumerian clay tablets.

For example, because religious writings and tales were written down on clay tablets, we now have a better knowledge of the Sumerian belief system. There are various cuneiform tablets that include stories about the gods, such as Inanna’s descent to the underworld and Sumerian creation myth. While the first shows their views about mortality and the Afterlife, the second deals with Sumerian ideas about the creation of the universe. There is also the Sumerian King List, which is a fascinating cuneiform tablet that lists ancient Sumerian rulers, their alleged period of reign, and the location of their kingdoms.

It contains prehistoric monarchs and boasts thousands-year reigns, including 8 kings who reigned for a cumulative 241,200 years. The earliest recorded king whose historical existence has been archaeologically proved was Enmebaragesi of Kish, circa 2,600 BCE, according to most experts.

These latter dynastic monarchs are thus considered more credible; however, it should be emphasized that not all known dynasties are mentioned. Finally, despite the fact that hundreds of Sumerian clay tablets have been discovered, not all of them have been interpreted. More light may be thrown on the Sumerians as academics continue to decipher these tablets, allowing us to construct a more comprehensive picture of this ancient civilization.

Cuneiform, a Latin name that literally means “wedge-shaped,” was invented by the Sumerians in approximately 3,400 BCE. Its most advanced version comprised several hundred symbols that ancient scribes employed with a reed stylus to record phrases or syllables on damp Sumerian clay tablets. The tablets were then roasted or sun-dried to harden. Cuneiform appears to have been invented by the Sumerians for the prosaic purpose of maintaining accounts of commercial transactions, but it eventually evolved into a full-fledged system of writing utilized for anything from poems and history to legal codes and literature.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Did Sumerians Write On?

The Sumerian culture was responsible for creating history’s oldest known written language. Cuneiform writing was invented by Sumerian writers in Uruk, as a method of transaction records by making wedge-shaped dents in clay tablets with a reed stylus. Subsequent scribes would also carve cuneiform into various stone artifacts. Various combinations of these markings signified syllables, which could then be combined to make words. Cuneiform has survived as a strong writing tradition for almost 3,000 years. In addition to Sumerian, the script was employed by scribes from many civilizations throughout that period to record a variety of other languages that served as the common tongue of the Babylonian and Assyrian Empires.

Why Did Sumerian Merchants Use Cuneiform Tablets?

The Sumerians were compelled to establish one of the oldest land-and-sea commerce networks since their native country was mostly bereft of lumber, stone, and minerals. The island of Dilmun, which controlled the whole copper trade, may have been their most significant trading partner, but its merchants also made months-long excursions to Lebanon and Anatolia to obtain cedar wood and the Indus Valley to find gold and precious stones. Lapis lazuli, a blue valuable stone used in jewelry and artwork, was a favorite of the Sumerians, and there is evidence that suggests they may have traveled as far as Afghanistan to obtain it. In order to record their trade transactions, merchants employed cuneiform tablets to document these transactions.

Were the Sumerians Peaceful?

The Sumerian city-states were at war almost constantly, while having a similar language and cultural heritage, which gave rise to a number of distinct empires and kingships. King Eannatum of Lagash destroyed the neighboring city-state of Umma in a boundary dispute probably about 2,450 BCE, which is the earliest of these confrontations recorded in history. Eannatum built the gruesome limestone Stele of the Vultures, a monument depicting birds feeding on the flesh of his defeated foes, as a monument to mark his triumph.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Isabella, Meyer, “Sumerian Tablets – Discovery and Decoding of Ancient Cuneiform.” Art in Context. June 19, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/sumerian-tablets/

Meyer, I. (2023, 19 June). Sumerian Tablets – Discovery and Decoding of Ancient Cuneiform. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/sumerian-tablets/

Meyer, Isabella. “Sumerian Tablets – Discovery and Decoding of Ancient Cuneiform.” Art in Context, June 19, 2023. https://artincontext.org/sumerian-tablets/.