Pop Art – The Fusion of High Art and Popular Culture

In the 1950s, international art did a sudden and unexpected 180-degree turn. In the United States and the United Kingdom, a new art movement, pop art, began to grow in popularity. This new art movement took inspiration from the often mundane, consumerist, slightly kitschy, and mass-produced parts of popular culture. Pop artists like Andy Warhol, Richard Hamilton, and Roy Lichtenstein instigated a shift in our conception of high and low art forms. These artists drew attention to the growing consumerism in the markets and our art consumption.

A Brief Summary of the Pop Art Movement: What Is Pop Art

Many of us know artists like Andy Warhol, but what is Pop Art as a movement? When it comes to creating a Pop Art definition, we need to consider the type of Pop Art. There is some contention surrounding the original birthplace of pop art. Similar trends began appearing in England and America in the early 1950s. Pop art was a real 180-degree turn in the development of modernism from the Abstract Expressionist movement that came before it.

The Pop Art definition turned to tangible and accessible parts of popular culture as inspiration, replacing the traditional “high art” themes of classic history, mythology, morality, and abstraction. Pop art elevated the more mundane parts of popular culture to fine art, and today it is one of the most recognized modern art styles.

Key Pop Art Ideas

Pop Art may appear more trivial and superfluous than other traditional fine art movements. The bright colors, use of popular imagery, basic shapes, and thick outlines may suggest a more playful form of art, but the Pop Art movement is packed with underlying intricacies and social commentaries. Here is a little Pop Art background.

What Makes Art Fine?

The most prominent idea within the Pop Art movement was to blur the lines between what had previously been considered fine art and the more kitschy, mundane parts of popular culture. Pop artists celebrated items of consumerist value, insisting that there is no cultural hierarchy when it comes to worthy subjects of artistic creation. Pop artists borrowed inspiration from any source, regardless of cultural value.

Shocked Withdrawal or Cool Acceptance?

The works of Abstract Expressionist artists are typically highly emotive. In contrast, Pop Art paintings and collages tend to be more removed and distant. Although Pop artworks often explore diverse cultural attitudes and integral parts of social life, they do so in a cool and relatively unemotional way. Art historians have hotly debated whether this distance is a shocking withdrawal from the cultural themes that Pop Art explores or whether it is the opposite. Perhaps the coolness reflects an acceptance of popular culture.

How Does Pop Art Explore Cultural Trauma?

An integral part of the Abstract Expressionism that preceded Pop Art was the search for trauma within the soul. Pop artists searched for the same soul trauma, but on a cultural level. In Pop Art, the worlds of popular imagery, cartoons, advertisement, and cultural phenomena like the boom of fast-food restaurants would mediate this social trauma.

In Pop Art, all these manifestations of a cultural trauma are significant, and they give the artist unmediated access to the deeper concerns of humankind.

The modern world is characterized by unmediated access to almost everything. From the built environment to the personal lives of celebrities, everything is available for consumption and critique. Pop Art reflects this access, drawing together various cultural elements to demonstrate that everything is connected.

Capitalist Critique or Enthusiastic Endorsement?

In England in particular, Pop Art artists embraced the media and manufacturing boom of the Second World War. Many view the wide use of commercial advertisement in Pop artworks as an endorsement of the capitalist marketplace. Some critics believe that Pop Art celebrates the growing consumerism of the modern age.

Others find an element of cultural critique buried within these multi-layered works. Pop artists elevated commonplace commercial objects to the status of fine art. By equating commercial goods with fine art, Pop artists draw our attention to the fundamental fact that art itself is a commodity.

Many Pop Art artists began as commercial artists. Ed Ruscha was a graphic designer, and Andy Warhol was also an incredibly successful magazine illustrator. Thanks to these early beginnings, these artists demonstrate fluency in the visual vocabulary of popular culture. These skills eased the ability of these artists to blend fine art and commercial culture seamlessly.

The Origins of the Pop Art Movement

The Pop Art movement is interesting because it developed simultaneously in the United States and England. The first sparks of the Pop Art movement were vastly different in each of these countries. As such, it is essential to begin considering them separately.

In the United States, Pop Art was a return to more representational art that used the irony of mundane reality to neutralize the personal symbolism of Abstract Expressionism. In contrast, early British Pop Art was more academic. British Pop artists used irony to explore and critique the explosive consumerism of post-war American popular culture.

Proto-Pop Art

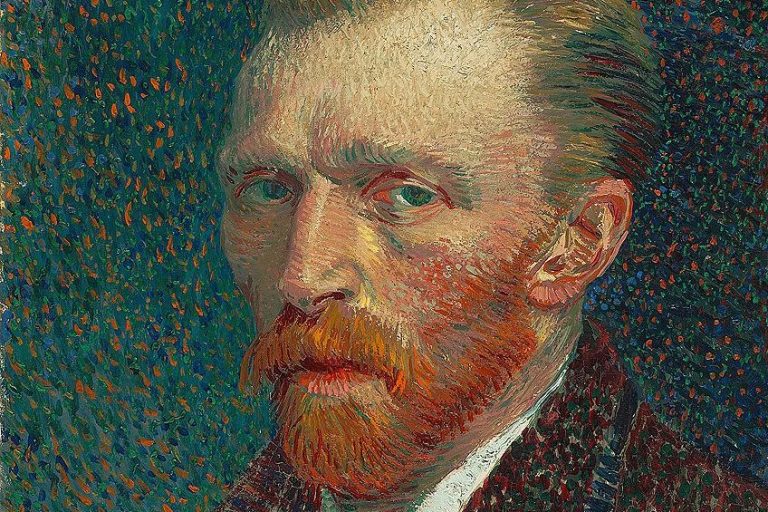

While the 1950s saw the beginning of American and British Pop Art, some European artists like Marcel Duchamp, Many Ray, and Francis Picabia predate the movement in their exploration of capitalist and modernist themes and styles.

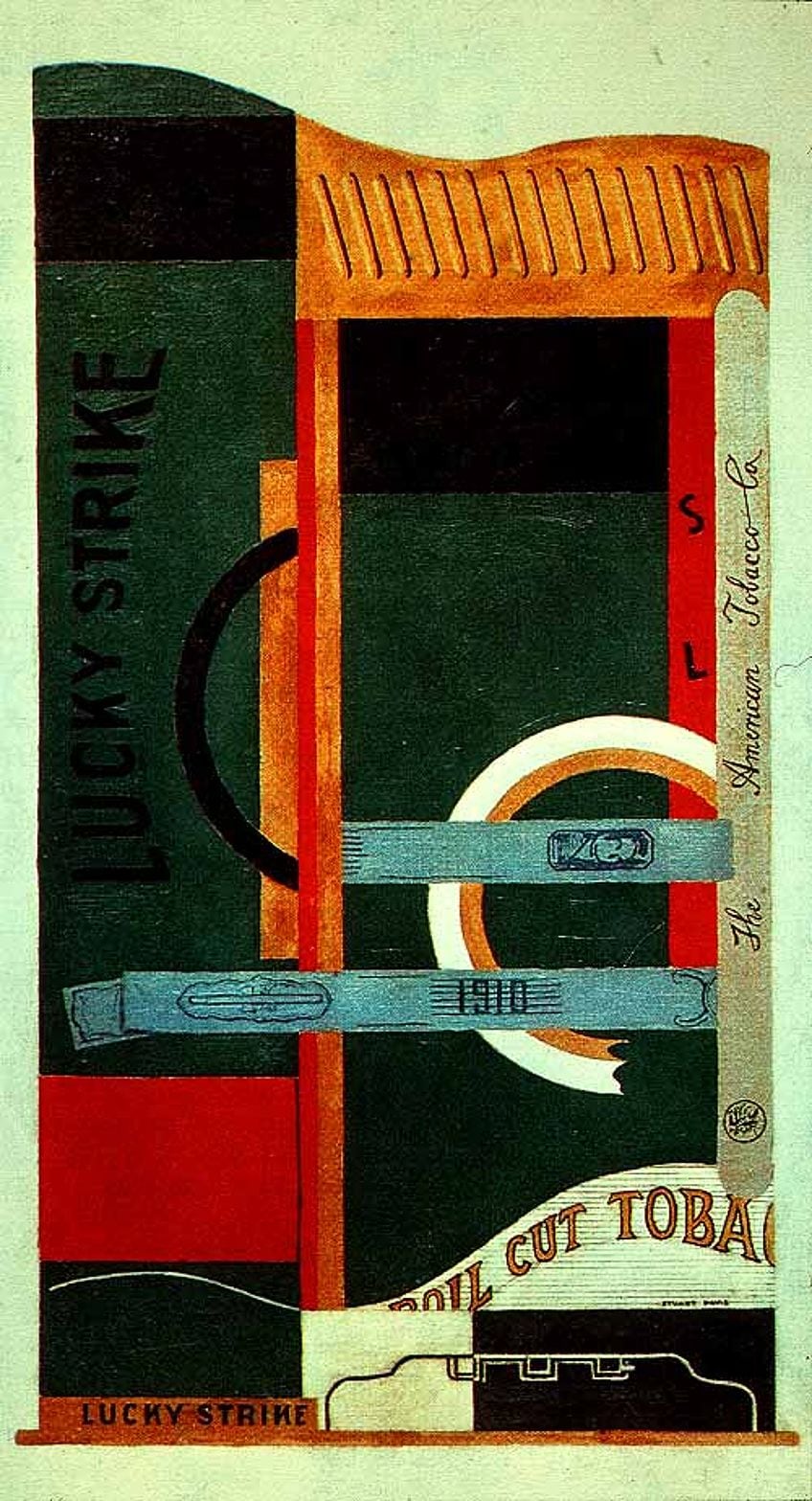

Some American artists hinted at the development of modern Pop Art as early as the 1920s. Artists like Stuart Davis, Gerald Murphy, Patrick Henry Bruce, and Charles Demuth created works that explored imagery from popular culture, including mundane commercial objects and advertising design.

The Independent Group: Pop Art in Great Britain

In London, the Independent Group of Artists was formed in 1952, and many consider this group to be the precursor to the new Pop movement. This gathering of young painters, sculptors, writers, architects, and critics hailed in the new Pop Art movement. This group of artists began meeting regularly in the 1950s and their discussions would center around developments in technology and science, the found object, and the place of mass culture in fine art.

Some notable members included the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, and the critics Reyner Banham and Lawrence Alloway. As these creatives began meeting in the 1950s, England was still gradually recovering from the post-war years, and much of the population were ambivalent about the popular culture in America.

The Independent Group shared this hesitancy towards the commercial character of American popular culture, but they were enthused about the rich world of pop culture, discussing science fiction, car design, Western movies, rock and roll music, billboards, and comic books at length.

1960 saw the first influences of American Pop in the Royal Society of British Artists’ annual young talent exhibition. By January of 1961, R. B. Kitaj, David Hockney, Joe Tilson, Billy Apple, Dereck Boshier, Peter Blake, Patrick Caulfield, Allen Jones, and Peter Phillips were planted firmly on the Pop Art map.

Billy Apple was responsible for designing the invitations and posters for the following two annual Young Contemporaries exhibitions. In the same year, Blake, Kitaj, and Hockney won prizes in Liverpool at the John-Moores Exhibition. During the 1961 summer break at the Royal College, Hockney and Apple visited New York together.

Finding a Pop Art Definition

When it comes to deciding who was the first to use the term “Pop Art”, there is a great deal of contention. In Britain, there are several possible sparks that led to the actual “Pop Art” term. Peter and Alison Smithson used the term in a 1956 article published in Ark Magazine. The article was called “But Today We Collect Ads.”

Richard Hamilton defined Pop in a letter he wrote, and Paolozzi also used the word Pop in his I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947) collage. John McHale’s son also believes that his father first used the term while conversing with Frank Cordell in 1954.

Lawrence Alloway is also often credited with first using the term in his 1958 essay, The Arts and the Mass Media. In this essay, however, he only uses the phrase “popular mass culture,” and he was referring to popular culture as products of mass media rather than works of art. In 1966, Alloway clarified these terms, but by this time, Pop Art had already made its way into schools and galleries.

America Pop Art Background

New York City was the birthplace of American Pop Art. In the middle of the 1950s, New York artists approached a significant crossroads in the development of modern art. In America Pop Art Artists could either follow in the footsteps of the Abstract Expressionists, or they could rebel against the formalism of modernist schools of thought. Naturally, many artists chose rebellion, and they began to experiment with non traditional forms and materials.

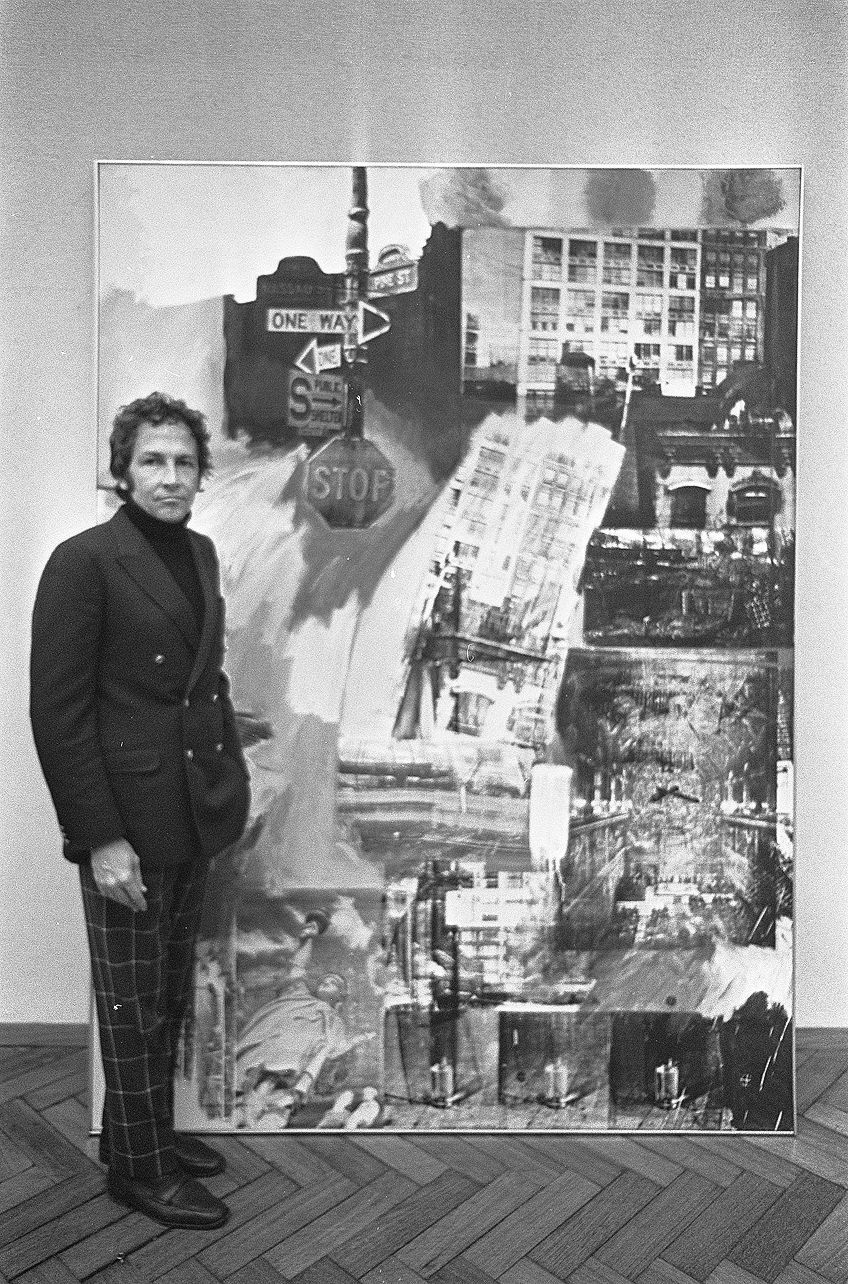

At this time, Jasper Johns was already causing a commotion with his abstract paintings referencing objects that “the mind already knows.” These objects included numbers, handprints, flags, letters, and targets. Other Pop Art artists like Robert Rauschenberg were using found images and objects alongside traditional oil paints. In the same way, the Fluxus movements and Allan Kaprow chose to include elements of the world around them in their artworks. Alongside others, these artists would later form the Neo-Dada movement.

Although Pop Art began emerging in the United States in the early 1950s, it was in the 1960s that the movement gained traction. At the Museum of Modern Art in 1962, Pop Art was introduced at a Symposium on Pop Art. As artists began to use advertising elements in modern art, commercial advertising began to incorporate elements of modern art. American advertising became very sophisticated, and American artists needed to find more dramatic styles to distance themselves from mass-produced materials.

While British Pop Art took a slightly humorous, romantic, and sentimental approach to American popular culture, American artists produced Pop Art that was typically more aggressive and bold. The British were distanced from the realities of American consumerist images, whereas American artists were bombarded with them daily.

Establishing American Modern Pop Art

Robert Rauschenberg took a great deal of influence from Dada artists, including Kurt Schwitters. Rauschenberg believed that painting relates both to the worlds of fine art but also everyday life. This opinion challenged the dominant modernist perspective of the time. Rauschenberg combined pop culture imagery and discarded objects in his work. In this way, Rauschenberg could draw a connection between his work and topical events in American society.

The silkscreen paintings that Rauschenberg completed between 1962 and 1964 combined magazine clippings from National Geographic, Newsweek, and Life with expressive brushwork. Rauschenberg’s early work is often classified as Neo-Dada because it is distinct from the American Pop Art style that flourished in the 1960s.

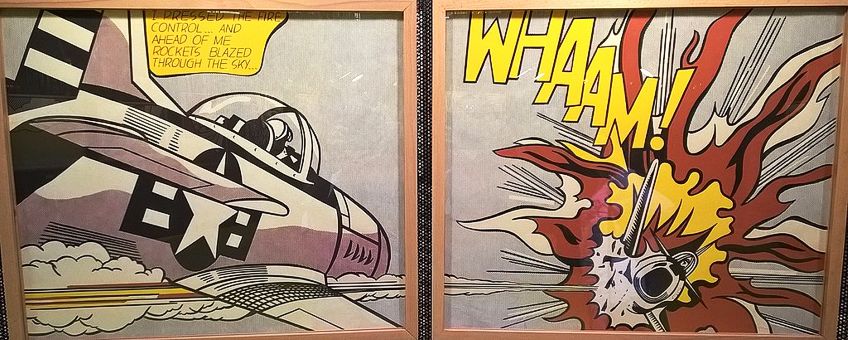

When it comes to prominent American Pop artists, we cannot forget Roy Lichtenstein. Lichtenstein’s use of parody in his works offers perhaps the best definition of Pop Art’s underlying premise. Lichtenstein produces precise, hard-edged compositions based on old-fashioned comic strips.

Using Magna and oil paints, Lichtenstein would appropriate and alter scenes from DC comics and others. It is easy to recognize the work of Lichtenstein by his use of Ben-Day dots, bold colors, and thick outlines. The artist effortlessly blends popular culture and fine art, integrating irony, popular imagery, and humor into his works.

American Pop Art versus British Pop Art

Pop Art emerged in both America and Britain at around the same time in the 1950s and 60s. The overarching Pop Art style is an amalgamation of the differences between the two nations. Although both countries found inspiration in the same subject matter, there are several distinctions between their styles.

The early British Pop Art found its inspiration in viewing American popular culture from a distance. With this distance came a certain level of romanticism and sentimentalism, as well as a significant amount of disdain.

British Pop artists took an academic approach to American popular culture, dissecting the power of American popular imagery in manipulating the lives of its citizens. The traditionally dry British sense of irony and parody seeped into British Pop Art.

American Pop artists, by contrast, lived and breathed American popular culture, and this lack of distance is apparent. American Pop Art was also, in part, a rebellion against other forms of modern art. Abstract Expressionism was the greatest impetus for American Pop artists, who wanted to move away from the highly emotive and personal symbolism of the style. As a result, American Pop artists use mundane, impersonal imagery in their works.

Trends, Concepts, and Styles in Pop Art

Following the transition from Neo-Dada to Pop Art, artists throughout the world became increasingly interested in using popular culture in their works. While members of the Independent Group were the first to use the term “Pop Art,” American artists quickly gravitated towards this new style.

Although the individual styles of Pop artists vary greatly, there are common underlying themes and concepts to the Pop Art movement. The use of imagery from popular culture is the most prominent feature throughout Pop artworks.

After the Pop Art movement took off in America, several European variants began emerging, including the German Capitalist Realist movement and the French Nouveau Réalisme.

The Tabular Image: Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton

European Pop artists maintained mixed feelings towards the popular culture of America, and these feelings are perhaps best conveyed through the Pop Art collages of Hamilton and Paolozzi. The artists simultaneously criticized the excess and exalted the mass-reproduced objects and images.

Members of the Independent Group, including Hamilton, were among the first to use mass media imagery in their works. Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, a 1956 collage by Hamilton, combines carefully sourced elements from mass media imagery to convey his belief that American culture was one of excess. Paolozzi dissects the barrage of mass media through his photo montage collages, like his 1947 work, I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything.

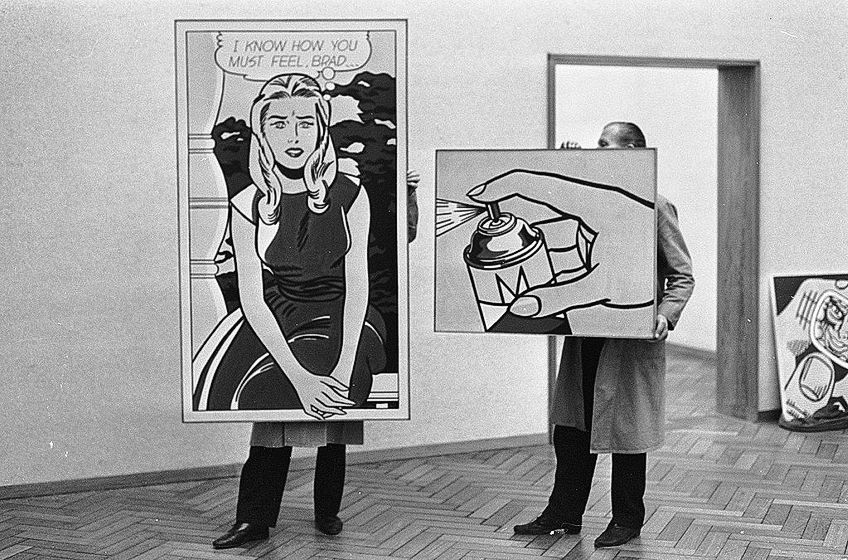

Pulp Culture: Roy Lichtenstein

Part of the significance of Lichtenstein’s work is his ability to create stunning compositions despite using comic books as his subject matter. Not only did Lichtenstein appropriate imagery from mass-produced picture books, but he also applied the techniques of comic books, namely Ben-Day dots.

Although he uses popular imagery in his paintings, Lichtenstein’s works are not mere duplicates. Lichtenstein would focus on a single panel from a comic book, often cropping it down to alter the story. Lichtenstein would also add or remove various elements and play around with language and text. Lichtenstein further blurred the line between fine art and mass reproduction by hand painting the traditionally machine-printed dots.

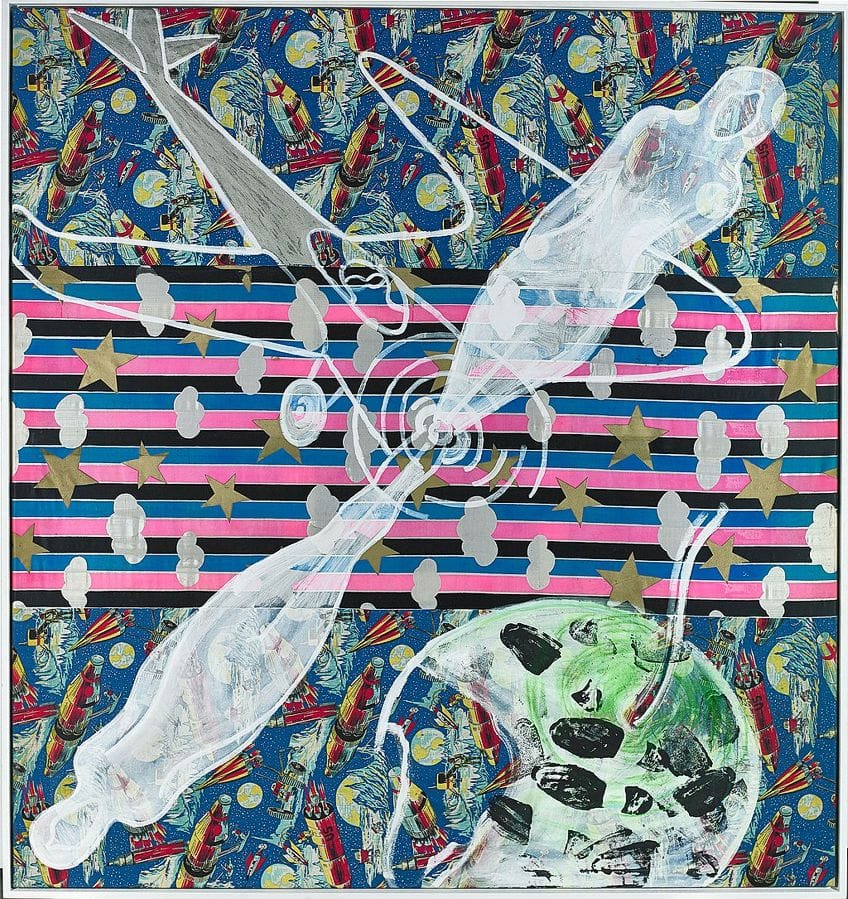

The Monumental Image: James Rosenquist

Rosenquist was another artist who appropriated popular culture images directly in his paintings. However, like Lichtenstein, Rosenquist did not simply produce copies. Instead, Rosenquist juxtaposes various celebrities, products, and images in a Surrealist manner.

Many of Rosenquist’s works also include striking political messages. Rosenquist would begin his works by creating collages of advertisements and photo-spread clippings. He would then transform the simple collage into a cohesive painting.

Rosenquist began his artistic career painting billboards, and he was able to transition perfectly into rendering his collages on monumental scales. Many of Rosenquist’s works were 20 feet wide or bigger. By inflating mundane images from popular culture on such a large scale, Rosenquist was able to elevate the ordinary to the status of fine art.

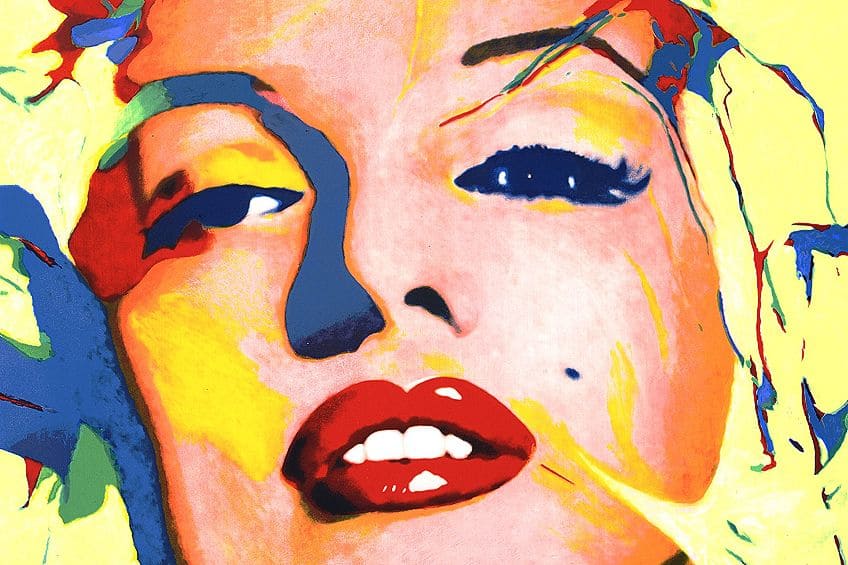

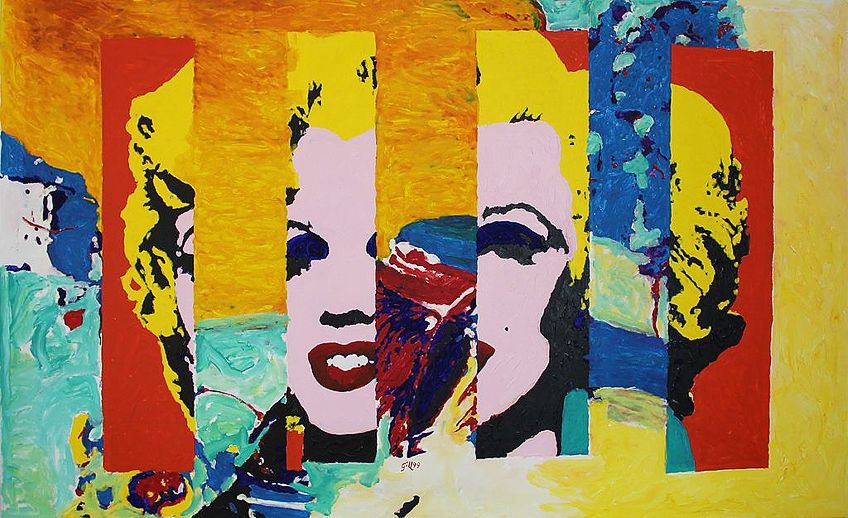

Repetition: Andy Warhol and Repetition

When you think of Pop Art, Andy Warhol’s name will likely pop into your mind. Warhol is one of the most famous Pop artists, and his style is iconic and instantly recognizable globally. Warhol is perhaps most well-known for his brightly colored celebrity portraits. Warhol experimented with many varied subject matters throughout his illustrious career.

The common thread underlying all of his work is the inspiration of mass consumerism and popular culture. Repetition is another key element of Warhol’s work, commenting on the mass reproduction within the modern age.

Coca-Cola bottles and Campbell’s soup cans feature prominently in many of Warhol’s earliest works. Warhol would reproduce the images of these items ad infinitum, turning gallery walls into supermarket shelves. To further mimic and parody mass-production, Warhol began to screenprint his works, which had previously been hand-painted.

By insisting on creating his works mechanically, Warhol was rejecting the notion of artistic genius and authenticity. In its place, Warhol emphasized the commodification of art in the modern age, equating paintings with cans of soup. Both soup and paintings can be bought and sold as consumer goods, and both have inherent material worth. Warhol went even further, equating mass-produced consumer goods with celebrity figures like Marilyn Monroe.

Pop Sculpture: Claes Oldenburg

Although sculpture seems like a perfect medium for Pop Art, Oldenburg was one of the very few Pop artists to explore it. Today Oldenburg is famed for his soft sculptures, and enormous public replicas of mundane consumerist objects, many of his earlier works were on a much smaller scale. In 1961, Oldenburg created an exhibition called The Store where he rented a storefront in New York that sold his small sculptural replicas of mundane objects.

Shortly after The Store, Oldenburg began to experiment with soft sculptures. Oldenburg would use fabric and stuffing to construct large ice cream cones, slices of cake, mixers, and other consumerist items. These soft sculptures would collapse in on themselves, perhaps commenting on the hollowness of consumerist items.

Throughout his career, Oldenburg focused entirely on commonplace objects. Following his soft sculptures, Oldenburg began to create grand pieces of public art. His 1974 Clothespin sculpture in Philadelphia was 45 feet high. A sense of playfulness towards presenting the mundane in unconventional ways permeates all Oldenburg’s works, regardless of the scale.

Pop Art in Los Angeles

While New York City was the birthplace of American Pop Art, Los Angeles had its own brand. The New York scene was far more rigid than Los Angeles, which did not have the established critics and galleries of East Coast America. This lack of rigidity translates into the Pop artists who worked and lived in Los Angeles.

In 1962, the Pasadena Art Museum held the first Pop Art survey. The New Painting of Common Objects exhibition showcased the works of Lichtenstein, Warhol, and Los Angeles artists Joe Goode, Ed Ruscha, Robert Dowd, and Phillip Hefferton.

There was another Pop Art aesthetic practiced by Los Angeles Pop artists like Billy Al Bengston. The works in this aesthetic referenced motorcycles and surfing, and used new materials like automobile paint. Making the familiar strange was a central theme in much of Los Angeles Pop art.

Using unexpected and new combinations of media and images, and shifting the focus away from consumer goods, Los Angeles Pop artists moved Pop Art beyond pure replication. These artists began to evoke particular attitudes, feelings, and ideas in their works, basing their compositions on experiences and pushing the boundaries between popular culture and fine art.

Signage: Ed Ruscha

Ruscha was one of the leading Los Angeles Pop artists, and he used a variety of media in his works. Most of his works were either painted or printed, and he often used phrases or words as the subjects of his early works, highlighting the omnipresence of Los Angeles signage. Ruscha’s works blur the lines between abstraction, painting, and advertising signage, which undermined the divisions between commerce and aesthetics.

Most of Ruscha’s work is highly conceptual, and he tended to focus on the idea behind the work rather than the image itself. As with many Pop artists, Ruscha’s work went beyond simply reproducing consumerist images and objects. Instead, he examined the interchangeability of experience, text, image, and place.

French Nouveau Réalisme

In 1960, art critic Pierre Restany founded the Nouveau Réalisme movement by drafting the “Constitutive Declaration of New Realism.” This document claimed that Nouveau Réalisme was a new way of perceiving reality. Nine artists, united in their appropriation of mass culture, signed the declaration in the workshop of Yves Klein. The principle of poetically recycling the reality of the industry, urban life, and advertisement is evident in the decollage techniques of Villegle. New images were created by cutting through layers of posters.

The American Pop Art concerns with commercial culture were echoed in the Nouveau Réalisme movement. However, these artists were more concerned with objects rather than paintings.

German Capitalist Realism

The German counterpart to American and British Pop Art was the Capitalist Realism movement. In 1963, Sigmar Polke founded the movement, which used a mass-media aesthetic to explore objects from commodity culture.

Other artists like Konrad Leug and Gerhard Richter sought to expose the superficiality and consumerism of modern Capitalist societies by using aesthetics and imagery in their own work. Richter scrutinized culture through photography, Polke explored the creative capacity of mechanical production, and Leug explored the imagery of Pop culture.

Famous Pop Art Pieces

As with any movement, there is a great amount of diversity within Pop Art. The movement lays claim to many varied artists, each of whom made valuable contributions to developing modernism. In this section of the article, we explore some of the most famous Pop Art pieces and investigate their contribution to one of the most well-known art movements of the 21st century.

Eduardo Paolozzi: I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947)

Eduardo Paolozzi was a Scottish-born artist and sculptor who was a crucial member of the post-war Avant-Garde in England. In 1947 he completed this collage of popular images, a piece which hints at the Pop Art movement that would follow only a few years later. Paolozzi uses a Coca-Cola advert, the cover of a pulp fiction novel, and a recruitment advertisement for the military in this collage.

Like a lot of British Pop Art, this piece reflects a darker, more critical tone. The work is a perfect example of how British Pop Art reflected on the gap between the harsh political and economic reality of post-war Britain and the affluent glamour idealized in popular American culture. Paolozzi became a member of the Independent Group, and much of his work investigates the impact of mass culture and technology on fine or high art.

Paolozzi’s choice of the collage medium nods to the photomontage influences of the Dadaist and Surrealist movements. By physically collating a wide range of popular culture images and Pop Art ideas on a single page, Paolozzi recreates the everyday barrage of mass-media images in the modern world.

Richard Hamilton: Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956)

Collage was a popular form of early Pop Art, and this collage by Richard Hamilton is another rich example. Hamilton made this piece for the 1956 This is Tomorrow exhibition. This collage was the advertisement for the exhibit, and it was featured in the catalog. Many critics cite this collage as the very first work of the British Pop Art movement.

In the collage, we can see a modern-day Adam and Eve. Rather than biblical figures, these two are a burlesque dancer and a bodybuilder. These two foundational characters sit within a milieu of modern-day conveniences, including canned ham, a vacuum cleaner, and a television.

Hamilton cut each element from advertisements in magazines. The scene that Hamilton creates both upholds and exploits consumerism. Hamilton also offers a stinging critique of the decadence of the American post-war years.

James Rosenquist: President-Elect (1960-61)

This painting is the first piece on our list that is not a collage, but it did start its life as one. Rosenquist began creating this piece by making a collage with three distinct elements. Each element is cut from various mass-media items. The face of John F. Kennedy, a yellow Chevrolet, and a piece of cake adorn the painting. Rosenquist then transformed the amalgamation of consumerist objects into a monumental, photo-realistic painting.

Rosenquist stated that he had chosen to use the face of John F. Kennedy from one of his campaign posters alongside other elements taken from advertisements because he was interested in the sudden trend of people advertising themselves like consumer goods.

Rosenquist skilfully blends the juxtaposing elements of a collage in painting, proving his artistic talent and ability to offer striking cultural and political commentary through popular imagery.

Claes Oldenburg: Pastry Case, I (1961-62)

Although the sculpture was not the most common medium in the Pop Art movement, Oldenburg was the most notorious Pop sculptor. If you have ever seen any large, playfully absurd sculptures of inanimate objects or food, they were likely created by Oldenburg.

Pastry Case, I is a collection of works that Oldenburg exhibited at his 1961 The Store installation. The Store was a shop on the Lower East Side in New York, where Oldenburg created and displayed sculptural objects. Oldenburg’s plaster candied apples, strawberry shortcakes, and other consumer items were displayed in his shop-like installation.

Not only were Oldenburg’s pieces commercial products, but he also sold them from The Store at very low prices. The installation and the Pastry Case I collection comment on the relationship between commercial goods and art as commodities. Although Oldenburg sold these pieces as if they were mass-produced consumer goods, they were all delicately hand-made.

Oldenburg includes yet another cultural critique in these pieces through the lavishly expressive brushstrokes he uses to paint each object. Many believe that these brushstrokes mock the work of Abstract Expressionists. Criticism of Abstract Expressionism is a common thread throughout much Pop Art. Oldenburg creates a highly ironic environment as he combines highly commercial items with Expressionist brushstrokes.

Roy Lichtenstein: Drowning Girl (1963)

Towards the beginning of the 1960s, Lichtenstein was growing in fame. Lichtenstein specialized in paintings that drew on popular comics, and this is one of his most well-known pieces. Before Lichtenstein, no Pop artist had ever focused exclusively on cartoon imagery. Other artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg had both used popular imagery in their works previously, but Lichtenstein was the first to focus on cartoons.

It was the work of Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol which hailed the beginning of the Pop Art movement. While Lichtenstein worked exclusively with comics, he did not copy them directly from their sources. Instead, he used intricate techniques, cropping comic images to create novel and exciting compositions. Lichtenstein would also alter the writing in each of his paintings, condensing it and pointing to the visual significance of writing in the comic genre.

Drowning Girl is a good example of this technique because the original source image included the girl’s boyfriend standing above her on a boat. In his paintings, Lichtenstein re-appropriates these aspects of commercial art. In doing so, he challenges existing views about the hierarchy of art forms.

As with many Pop art paintings, it is unclear whether Lichtenstein endorses or critiques the comic form in his paintings. Does he approve of the comic style and mimic it to increase its value, or is it a scathing critique? The answer to this question is left up to the interpretation of the viewer.

Sigmar Polke: Bunnies (1966)

Sigmar Polke was a significant figure in German Capitalist Realism, having co-founded the movement in 1963. Alongside other artists like Konrad Leug and Gerhard Richter, Polke began painting images of popular culture. These paintings elicit a cool cynicism about the state of the German economy following the Second World War. These Pop Art paintings also invoke a sense of genuine nostalgia for the images themselves.

As Lichtenstein began replicating Ben-Day dots, Polke began mimicking commercial four-color printing dot patterns. In his painting Bunnies, Polke recreates a Playboy Club image of four of their costumed bunnies. The disruption of the dot printing technique on the canvas interrupts the mass-marketing effects of sexual appeal. The closer the viewer gets to see the scantily clad women, the less they can see.

In most of his paintings, Polke does not invite the personal identification of the viewer. Instead, Polke’s paintings become allegories for losing the self in the torrent of commercial imagery. The dissonance between the heightened sexuality of the Playboy bunnies and the dot patterns echoes the conflict between a yearning for mass-commercial modern life and being simultaneously repelled by the very idea.

In comparison to New York Pop artists, Polke’s work is much more openly critical of the consumerism within popular culture. These views are rooted in the Capitalist Realism movement. Rather than offering shielded and slightly covert critiques of popular culture, Polke tackles it head-on.

Ed Ruscha: Standard Station (1966)

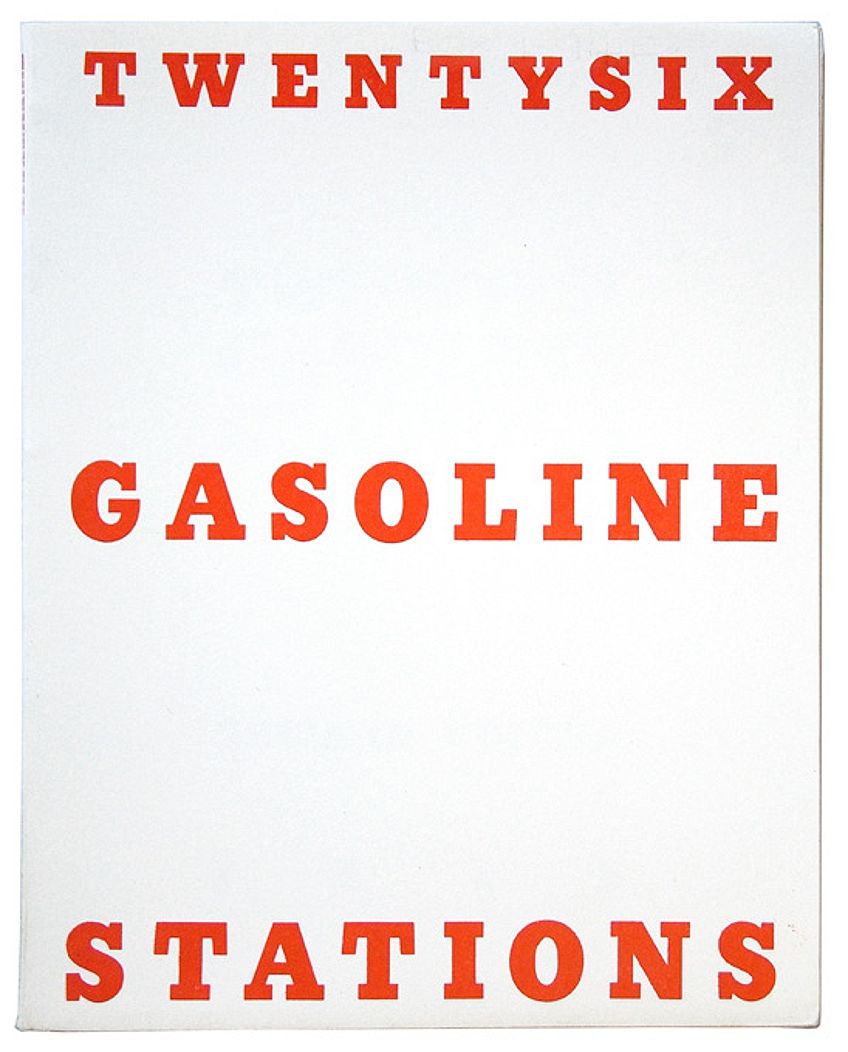

On the West Coast of America, Ed Ruscha was one of the most prominent Pop photographers, printmakers, and painters. Much of Ruscha’s work is a unique and colorful blend of Hollywood imagery, the Southwestern landscape, and commercial culture. The gas station, like the one in Standard Station, is a common motif throughout his work. In fact, in his book called Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), Ruscha documents a road trip he took through the Southwestern countryside.

In this painting, Ruscha is able to mold the ordinary and prosaic image of a gas station into an emblem of consumerist American culture. Ruscha screen prints this image, which flattens the perspective and reflects the commercial advertisement aesthetic. It is also possible to see Ruscha’s early experiments with interplaying text and language. In his later works, Ruscha would build on these early experiments and language would become an integral part of his conceptual works.

David Hockney: A Bigger Splash (1967)

Hockney created this considerable canvas of 94 squared inches from a reference photo in a pool magazine. For Hockney, the idea that it was possible to capture a fleeting event from a photograph in a painting was intriguing. While the moment of the splash was brief, the process of painting was much longer. Hockney manages to contrast the static rigidity of the geometric house, palm trees, pool edge, bright yellow diving board with the dynamism of the water splash. The result is an intentionally disjointed feeling.

The artificial stylization of this painting is typical of the Pop Art style.

Andy Warhol: Campbell’s Soup I (1968)

This painting is one of a whole series on Campbell’s Soup Cans by Andy Warhol. Unlike the works of Abstract Expressionists, Warhol never intended for people to celebrate these paintings for their compositional style or form.

Warhol is one of the most famous Pop artists, and he is best known for using universally recognizable popular imagery in a fine art context. In addition to his series on Campbell’s Soup Cans, Warhol also used the face of Marilyn Monroe, Mickey Mouse, and other famous figures.

By presenting these various popular images in a repetitive style, Warhol created a sense of mass-production in the context of fine or high art. For Warhol, it was not a case of emphasizing or celebrating popular imagery, but rather to provide a social commentary about consumerism. In modern times, commodities like celebrities, soup, and cartoons, become identifiable with a single glance.

Although Warhol painted this early series, he quickly turned to screenprinting. Not only was screenprinting far more economical, but he could infuse his mass-produced commodities with an even greater sense of mass-production. In Warhol’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, he presented 100 canvases of Campbell’s Soup Cans. This exhibit at the Ferus Gallery immediately placed Warhol on the world map and flung him to greater heights.

Pop Art is certainly one of the most well-known art movements of the 21st century. In the wake of global war and hardship, the movement was a thoroughly modern examination of the growing consumerism and excess of the modern world. Behind the bright colors, playful compositions, and absurd aesthetic lies a cutting cultural critique.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Isabella, Meyer, “Pop Art – The Fusion of High Art and Popular Culture.” Art in Context. April 19, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/pop-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 19 April). Pop Art – The Fusion of High Art and Popular Culture. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pop-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Pop Art – The Fusion of High Art and Popular Culture.” Art in Context, April 19, 2021. https://artincontext.org/pop-art/.