Loading AI tools

Property is any physical or intangible entity that is owned by a person or jointly by a group of people. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property has the right to consume, sell, rent, mortgage, transfer, exchange or destroy their property, or to exclude others from doing these things.

In economics and political economy, there are three broad forms of property: private property, public property, and collective property (also called cooperative property).

- Birth and wealth are conferred on some men as imperiously by nature, as genius, strength, or beauty.

- John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson, November 15, 1813, in The Portable John Adams (2004), p. 504.

- Property is surely a right of mankind as really as liberty. Perhaps, at first, prejudice, habit, shame or fear, principle or religion, would restrain the poor from attacking the rich, and the idle from usurping on the industrious; but the time would not be long before courage and enterprise would come, and pretexts be invented by degrees, to countenance the majority in dividing all the property among them, or at least, in sharing it equally with its present possessors. Debts would be abolished first; taxes laid heavy on the rich, and not at all on the others; and at last a downright equal division of every thing be demanded, and voted. What would be the consequence of this? The idle, the vicious, the intemperate, would rush into the utmost extravagance of debauchery, sell and spend all their share, and then demand a new division of those who purchased from them. The moment the idea is admitted into society, that property is not as sacred as the law of God, and that there is not a force of law and public justice to protect it, anarchy and tyranny commence. If "Thou shall not covet," and "Thou shall not steal," are not commandments of Heaven, they must be made inviolable precepts in every society, before it can be civilized or made free.

- John Adams, Ch. 1 Marchamont Nedham: The Right Constitution of a Commonwealth Examined, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government (1787).

- Property rights the Founding Fathers deemed "sacred as the law of God" included property in human beings.

- The Constitution of the United States recognises slaves as property, and pledges the Federal Government to protect it. And Congress cannot exercise any more authority over property of that description than it may constitutionally exercise over property of any other kind.

- Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- Property rights the Founding Fathers deemed "sacred as the law of God" included property in human beings.

- Property must be secured, or liberty cannot exist.

- John Adams, Discourses on Davila : A Series of Papers on Political History first published in the Gazette of the United States (1790-1791) ; (Downloadable PDF of 1805 edition); republished with modernized spelling in The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States vol. VI (1851)

- As long as Property exists, it will accumulate in Individuals and Families. As long as Marriage exists, Knowledge, Property and Influence will accumulate in Families.

- John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson (16 July 1814)

- Nature gave all things in common for the use of all; usurpation created private rights. Property hath no rights. The earth is the Lord's, and we are his offspring. The pagans hold earth as property. They do blaspheme God.

- Ambrose of Milan, in The Cry for Justice (1915), p. 397

- γεωμετρῆσαι βούλομαι τὸν ἀέρα

ὑμῖν διελεῖν τε κατὰ γύας.- I intend to measure out the air for you—dividing it in surveyed lots.

- Aristophanes, Meton in The Birds, line 995, as translated by Ian Johnston

- A man might say, "The things that are in the world are what God has made. ... Why should I not love what God has made?" ... Suppose, my brethren, a man should make for his betrothed a ring, and she should prefer the ring given her to the betrothed who made it for her, would not her heart be convicted of infidelity? ... God has given you all these things: therefore, love him who made them.

- Augustine of Hippo, Ten Homilies on the First Epistle of John (414), Second Homily, as translated by John Burnaby (1955), pp. 275-276

- Behold how only a few things suffice for you; nor does God ask much of you. Seek as much as He has given you, and from that take as much as is necessary; the superfluous things which remain are the necessaries of others. The superfluities of the rich are the necessaries of the poor. They who possess superfluities possess the goods of others.

- Augustine of Hippo Patrologia Latina, Vol 37, p. 1922

- "But whom do I treat unjustly," you say, "by keeping what is my own?" Tell me, what is your own? What did you bring into this life? From where did you receive it? It is as if someone were to take the first seat in the theater, then bar everyone else from attending, so that one person alone enjoys what is offered for the benefit of all in common — this is what the rich do. They seize common goods before others have the opportunity, then claim them as their own by right of preemption. For if we all took only what was necessary to satisfy our own needs, giving the rest to those who lack, no one would be rich, no one would be poor, and no one would be in need.

- Basil of Caesarea, Homily 6, “I Shall Tear Down My Barns,” C. P. Schroeder, trans., in Saint Basil on Social Justice (2009), p. 69.

- Who are the greedy? Those who are not satisfied with what suffices for their own needs. Who are the robbers? Those who take for themselves what rightfully belongs to everyone. And you, are you not greedy? Are you not a robber? The things you received in trust as a stewardship, have you not appropriated them for yourself? Is not the person who strips another of clothing called a thief? And those who do not clothe the naked when they have the power to do so, should they not be called the same? The bread you are holding back is for the hungry, the clothes you keep put away are for the naked, the shoes that are rotting away with disuse are for those who have none, the silver you keep buried in the earth is for the needy. You are thus guilty of injustice toward as many as you might have aided, and did not.

- Basil of Caesarea, Homily 6, “I Shall Tear Down My Barns,” C. P. Schroeder, trans., in Saint Basil on Social Justice (2009), p. 70.

- How is property given? By restraining liberty; that is, by taking it away so far as necessary for the purpose. How is your house made yours? By debarring every one else from the liberty of entering it without your leave.

- Jeremy Bentham, "A Critical Examination of the Declaration of Rights; Article II" in The Works of Jeremy Bentham, Vol. II (1839), p. 503.

- PROPERTY, n. Any material thing, having no particular value, that may be held by A against the cupidity of B. Whatever gratifies the passion for possession in one and disappoints it in all others. The object of man's brief rapacity and long indifference.

- Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary (1911).

- Humanity ... is never stationary. Its progressive march leads it to equality. Its regressive march goes back through every stage of privilege to human slavery, the final word of the right to property.

- Louis Auguste Blanqui, in "August Blanqui, Heretical Communist," Radical Philosophy 185 (2014)

- Here is an untaught ordinary person, who has no regard for the noble ones and is unskilled and undisciplined. ... He conceives himself as earth, he conceives himself in earth, he conceives himself apart from earth, he conceives earth to be ‘mine,’ he delights in earth. Why is that? Because he has not fully understood it, I say. ... He conceives himself in beings, he conceives himself apart from beings, he conceives beings to be ‘mine,’ he delights in beings. Why is that? Because he has not fully understood it, I say. ... He conceives himself in gods, he conceives himself apart from gods, he conceives gods to be ‘mine,’ he delights in gods. Why is that? Because he has not fully understood it, I say.

- Gautama Buddha, Mulapariyaya Sutta

- True independence – meaning the willingness to challenge a forceful CEO when something is wrong or foolish – is an enormously valuable trait in a director. It is also rare. The place to look for it is among high-grade people whose interests are in line with those of rank-and-file shareholders – and are in line in a very big way.

... Charlie and I love such honest-to-God ownership. After all, who ever washes a rental car?- Warren Buffett, Chairman's Letter - 2003. Berkshire Hathaway (February 27, 2004).

- You are no sister of ours; what shadow of proof is there? Here are our parchments, our padlocks, proving indisputably our money-safes to be ours, and you to have no business with them. Depart!

- Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present (1843).

- All possessions are by nature unrighteous when a man possesses them for personal advantage as being entirely his own, and does not bring them into the common stock for those in need.

- Clement of Alexandria, The Rich Man's Salvation, as translated by G. W. Butterworth, in Clement of Alexandria (Harvard University Press: 1979), p. 337.

- We are passing from an age when the emphasis in all our legislation has been upon property over into an age when the emphasis is going to be more and more upon life. Not that we shall fail to recognize the sacred rights of property. I am one of the first to acknowledge the sacred rights of property. Why? Not because of its material intrinsic value,—no, not that,—but because property represents crystalized human life. That is the reason it is sacred. But when it comes into competition, in warfare with human life itself the decision of the future is going to be more often in the interest of life and less often in the interest of property. Do you realize that ninety-five per cent of all our statutes on our books here in this State, and throughout the country, deal with the protection of property, and only about five per cent of them deal with the protection of life? That was inevitable, for it is a part of our evolutionary, or growing-up process. But the time is coming when, if there is a conflict between stocks, bonds and dividends on the one hand and men, women and children on the other, the emphasis is more often going to be given in favor of the men, women and children.

- George W. Coleman, "Speeches favoring and opposing the Initiative and Referendum," Debates in the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention 1917-1918, Vol. 2, (1918).

- The horseman serves the horse,

The neatherd serves the neat,

The merchant serves the purse,

The eater serves his meat;

'T is the day of the chattel,

Web to weave, and corn to grind;

Things are in the saddle,

And ride mankind.- Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Ode,” Complete Works (1883), vol. 9, p. 73

- A man should also take heart that life is like a revolving wheel, and in the end he or his son or his son's son may be reduced to taking tzedaka. He should not think, therefore, "How shall I diminish my property in order to give to the poor." Instead, he should realize that his property is not his own, but only deposited with him in trust to do with as the Depositor (God) wishes.

- Shlomo Ganzfried as translated by George Horowith in The Spirit of the Jewish Law (New York: 1953).

- In vain do they think themselves innocent who appropriate to their own use alone those goods which God gave in common; by not giving to others that which they themselves receive, they become homicides and murderers, inasmuch as in keeping for themselves those things which would alleviate the sufferings of the poor, we may say that every day they cause the death of as many persons as they might have fed and did not. When, therefore, we offer the means of living to the indigent, we do not give them anything of ours, but that which of right belongs to them. It is less a work of mercy which we perform than the payment of a debt.

- Gregory I, as quoted in George D. Herron, Between Caesar and Jesus (1899), pp. 111-112.

- The systems advocated by professed upholders of laissez-faire are in reality permeated with coercive restrictions of individual freedom. … What is the government doing when it "protects a property right"? Passively, it is abstaining from interference with the owner when he deals with the thing owned; actively, it is forcing the non-owner to desist from handling it, unless the owner consents. Yet Mr. Carver would have it that the government is merely preventing the non-owner from using force against the owner. This explanation is obviously at variance with the facts—for the non-owner is forbidden to handle the owner's property even where his handling of it involves no violence or force whatever. … In protecting property the government is doing something quite apart from merely keeping the peace. It is exerting coercion wherever that is necessary to protect each owner, not merely from violence, but also from peaceful infringement of his sole right to enjoy the thing owned.

- Robert Hale, “Coercion and Distribution in a Supposedly Non-Coercive State,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Sep., 1923), pp. 470-494.

- We stand for the maintenance of private property... We shall protect free enterprise as the most expedient, or rather the sole possible economic order.

- Adolf Hitler, as quoted in Der Fuehrer, Hitler's Rise to Power, by Konrad Heiden. Statement of the 1920.

- All the main thing that I speak for, is because I would have an eye to property. I hope we do not come to contend for victory—but let every man consider with himself that he do not go that way to take away all property. For here is the case of the most fundamental part of the constitution of the kingdom, which if you take away, you take away all by that.

- Henry Ireton, as quoted in The Making of the English Working Class (1963), p. 22

- Poor, wretched, and stupid peoples, nations determined on your own misfortune and blind to your own good! You let yourselves be deprived before your own eyes of the best part of your revenues; your fields are plundered, your homes robbed, your family heirlooms taken away. You live in such a way that you cannot claim a single thing as your own; and it would seem that you consider yourselves lucky to be loaned your property, your families, and your very lives. All this havoc, this misfortune, this ruin, descends upon you not from alien foes, but from the one enemy whom you yourselves render as powerful as he is. ... What could he do to you if you yourselves did not connive with the thief who plunders you?

- The Lord spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai, saying, ... "The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine. For you are strangers and sojourners with me."

- It is best for all to leave each man free to acquire property as fast as he can. Some will get wealthy. I don't believe in a law to prevent a man from getting rich; it would do more harm than good. So while we do not propose any war upon capital, we do wish to allow the humblest man an equal chance to get rich with everybody else. When one starts poor, as most do in the race of life, free society is such that he knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty-five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat, just what might happen to any poor man's son! I want every man to have the chance, and I believe a black man is entitled to it, in which he can better his condition. When he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him! That is the true system.

- Abraham Lincoln, "Allow the humblest man an equal chance" speech (6 March 1860) at New Haven, Connecticut.

- Property is the fruit of labor—property is desirable—is a positive good in the world. That some should be rich, shows that others may become rich, and hence is just encouragement to industry and enterprize. Let not him who is houseless pull down the house of another; but let him labor diligently and build one for himself, thus by example assuring that his own shall be safe from violence when built.

- Abraham Lincoln, reply to New York Workingmen's Democratic Republican Association (March 21, 1864), Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953), vol. 7, p. 259–60.

- It will perhaps be objected to this, that “if gathering the acorns, or other fruits of the earth, etc. makes a right to them, then any one may engross as much as he will.” To which I answer, Not so. The same law of nature, that does by this means give us property, does also bound that property too. God has given us all things richly ... But how far has he given it us? To enjoy. As much as any one can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labor fix a property in: whatever is beyond this, is more than his share, and belongs to others.

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Civil Government, pp. 355-356.

- All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need.

- Luke the Evangelist, Acts of the Apostles 2:44-45 NIV.

- As a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.

- James Madison, "Property", National Gazette (March 29, 1792) in Gaillard Hunt, ed., The Writings of James Madison vol. 6 (1906), p. 101. These words are inscribed in the Madison Memorial Hall, Library of Congress James Madison Memorial Building.

- But to make the comparison applicable, we must compare Communism at its best, with the regime of individual property, not as it is, but as it might be made. ... The laws of property have never yet conformed to the principles on which the justification of private property rests.

- J. S. Mill, Principles of Political Economy, p. 14

- People with advantages are loath to believe that they just happen to be people with advantages. They come readily to define themselves as inherently worthy of what they possess; they come to believe themselves 'naturally' elite, and, in fact, to imagine their possessions and their privileges as natural extensions of their own elite selves.

- C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (1956), p. 14.

- If you want to be perfect, go, sell your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.

- Jesus, as reported by Matthew the Apostle, Matthew 19:21 NIV.

- We are a band of brothers and native to the soil, fighting for the property we gained by honest toil.

- Harry McCarthy, "The Bonnie Blue Flag" (1861).

- "Among the beasts of prey, man is certainly the worst." This expression, very commonly made nowadays, is only relatively true. Not man as such, but man in connection with wealth is a beast of prey. The richer a man, the greater his greed for more. We may call such a monster the "beast of property". It now rules the world, makes mankind miserable, and gains in cruelty and voracity with the progress of our so-called "civilization".

- Johann Most, The Beast of Property (1884)

- Either by direct brute force, by cunning, or by fraud, this horde has from time to time seized the soil with all its wealth. The laws of inheritance and entail, and the changing of hands, have lent a "venerable" color to this robbery, and consequently mystified and erased the true character of such actions. For this reason, the "beast of property" is not yet fully recognized, but is, on the contrary, worshipped with a holy awe.

- Johann Most, The Beast of Property (1884)

- The league at Allstedt wanted to establish this principle, Omnia sunt communia, ‘All property should be held in common’ and should be distributed to each according to his needs, as the occasion required. Any prince, count, or lord who did not want to do this, after first being warned about it, should be beheaded or hanged.

- Thomas Müntzer, in Revelation and Revolution: Basic Writings of Thomas Müntzer (1993), p. 200.

- The stinking puddle from which usury, thievery and robbery arises is our lords and princes. They make all creatures their property—the fish in the water, the birds in the air, the plant in the earth must all be theirs. Then they proclaim God's commandments among the poor and say, "You shall not steal."

- Thomas Müntzer, Letter to the Princes, as cited in Transforming Faith Communities: A Comparative Study of Radical Christianity, p. 173.

- The doctrines held by the early Fathers of the Church on the nature of property are perfectly uniform. They almost all admit that wealth is the fruit of usurpation, and, considering the rich man as holding the patrimony of the poor, maintain that riches should only serve to relieve the indigent; to refuse to assist the poor is, consequently, worse than to rob the rich. According to the fathers, all was in common in the beginning: the distinctions mine and thine, in other words, individual property, came with the spirit of evil.

- Francesco Saverio Nitti, Catholic Socialism (1895), pp. 65-66

- Whoever makes something having bought or contracted for all other held resources used in the process (transferring some of his holdings for these cooperating factors), is entitled to it. The situation is not one of something’s getting made, and there being an open question of who is to get it. Things come into the world already attached to people having entitlements over them.

- Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia (1974), p. 160.

- Lacking much historical information and assuming (1) that victims of injustice generally do worse than they otherwise would and (2) that those from the least well-off group in the society have the highest probabilities of being the (descendants of) victims of the most serious injustice who are owed compensation by those who benefited from the injustices, ... then a rough rule of thumb for rectifying injustices might seem to be the following: organize society so as to maximize the position of whatever group ends up least well-off in the society.

- Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), pp. 231-232

- Nozick’s Theory, in spite of its apparent dedication to self-ownership, cannot escape the conclusion that women’s entitlement rights to those they produce must take priority of persons’ rights to themselves at birth. ... There is nothing about a woman’s production of an infant that does not easily fulfill the conditions of the principle of acquisition as Nozick specifies them.

- Susan Moller Okin, Justice, Gender, and the Family, (1989), pp. 82-83.

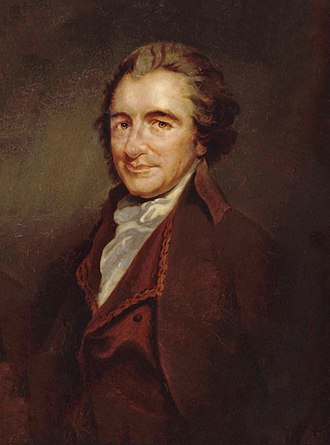

- It is the value of the improvements only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property.

- Thomas Paine, Agrarian Justice (1795), in Complete Works, vol. 2, p. 403

- If it had pleased them [the legislators] to order that this wealth, after having been possessed by fathers during their life, should return to the republic after their death, you would have no reason to complain of it.

- Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), Discourses on the Condition of the Great.

- The whole title by which you possess your property, is not a title of nature but of a human institution.

- Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), Discourses on the Condition of the Great.

- None [of the guardians] should have any property of his own beyond what is absolutely necessary. ... They will live together like soldiers in a camp. We will tell them that they have gold and silver of a divine sort in their souls as a permanent gift from the gods, and have no need of human gold in addition. And we will add that it is impious for them to defile this divine possession by possessing an admixture of mortal gold, because many impious deeds have been done for the sake of the currency of the masses, whereas their sort is pure.

- Plato, The Republic, 416d, C. Reeve, trans. (2004)

- Owners are the shareholders, living outside the process of production, idling in distant countryhouse and maybe gambling at the exchange. A shareholder has no direct connection with the work. His property does not consist in tools of him to work; with his property consists simply in pieces of paper, in shares of enterprises of which he does not even know the hereabouts. His function in society is that of a parasite. His ownership does not mean that he commands and directs the machines; this is the sole right of the director. It means only that he may claim a certain amount of money without having to work for it. The property in hand, his shares, are certificates showing his right - guaranteed by law and government, by courts and police - to participate in the profits; titles of companionship in that large Society for Exploitation of the World, that is capitalism.

- Anton Pannekoek, Workers Councils

- La propriété, c'est le vol!

- Property is theft!

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, What is Property? (1840), Ch. I: "Method Pursued in this Work. The Idea of a Revolution". Alternately translated as "Property is robbery!"

- What Allah has bestowed on His Messenger ... belongs to Allah, to His Messenger and to kindred and orphans, the needy and the wayfarer; in order that it may not (merely) make a circuit between the wealthy among you.

- Qur'an 59:7, as translated by Yusuf Ali

- Tenure of property is more of a duty than an actual right of possession. Property in the widest sense is a right that can belong only to society, which in turn receives it as a trust from Allah who is the only true owner of anything. ...

There can be no real place for personal possession unless it carries with it the rights of disposal and use. The condition on which this right must stand is that of wisdom in the disposal; if the disposal of property is foolish, then the ruler or society may withdraw this right of disposal. ...

The right of disposal depends on being mature and being able to fulfill one's duties; when the possessor does not meet these requirements, then the natural fruits of ownership come to an end.

- Sayyid Qutb, Social Justice in Islam (1953), pp. 132-133

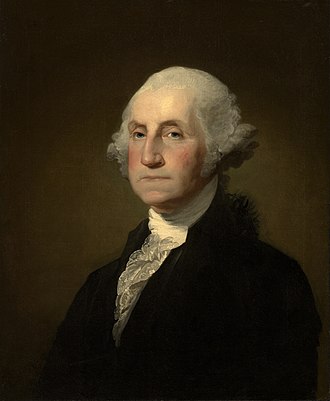

- In every civilized society property rights must be carefully safeguarded; ordinarily, and in the great majority of cases, human rights and property rights are fundamentally and in the long run identical.

- Theodore Roosevelt, "Citizenship in a Republic", a speech at the Sorbonne in Paris, France (23 April 1910)

- The first man who, having fenced off a plot of land, thought of saying, 'This is mine' and found people simple enough to believe him was the real founder of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders, how many miseries and horrors might the human race have been spared by the one who, upon pulling up the stakes or filling in the ditch, had shouted to his fellow men: 'Beware of listening to this imposter; you are lost if you forget the fruits of the earth belong to all and that the earth belongs to no one.'

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, 1755.

- The mere abolition of rent would not remove injustice, since it would confer a capricious advantage upon the occupiers of the best sites and the most fertile land. It is necessary that there should be rent, but it should be paid to the state or to some body which performs public services; or, if the total rental were more than is required for such purposes, it might be paid into a common fund and divided equally among the population.

- Bertrand Russell, The Basic Writings of Bertrand Russell, 2009.

- Theft is only punished because it violates the right of property; but this right is itself nothing in origin but theft.

- Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, Juliette (1797), p. 118

- Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776), V.i.b.12 (Part II).

- Violence, fraud, the prerogative of force, the claims of superior cunning—those are the sources to which titles may be traced. The original deeds were written with the sword, rather than with the pen; not lawyers, but soldiers, were the conveyancers; blows were the current coin given in payment; and for seals, blood was used in preference to wax. Could valid claims be thus constituted? Hardly. And if not, what becomes of the pretensions of all subsequent holders of estates so obtained? Does sale or bequest generate a right where it did not previously exist?

- Herbert Spencer, Social Statics, First Edition (1851), Chapter 9

- He who possesses many things is constantly on guard.

- Possessions are flying birds -- they never find a place to settle.

- The course of wisdom is neither to attack private property in general nor to defend it in general; for things are not similar in quality, merely because they are identical in name. It is to discriminate between the various concrete embodiments of what, in itself, is, after all, little more than an abstraction.

- R. H. Tawney, The Acquisitive Society (1920), p. 54

- Precisely in proportion as it is important to preserve the property which a man has in the results of his own efforts, is it important to abolish that which he has in the results of the efforts of someone else.

- R. H. Tawney, The Acquisitive Society (1920), p. 70.

- Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 17.

- As Nozick acknowledges, a modern state should not feel morally constrained by property holdings which might have had a Lockean pedigree but in fact do not. In this regard it is interesting that one of the main uses of Lockean theory these days is in defending the property rights of indigenous people—where a literal claim is being made about who had first possession of a set of resources and about the need to rectify the injustices that accompanied their subsequent expropriation.

- The freest government, if it could exist, would not be long acceptable, if the tendency of the laws were to create a rapid accumulation of property in few hands, and to render the great mass of the population dependent and penniless. In such a case, the popular power would be likely to break in upon the rights of property, or else the influence of property to limit and control the exercise of popular power. Universal suffrage, for example, could not long exist in a community where there was great inequality of property…. In the nature of things, those who have not property, and see their neighbors possess much more than they think them to need, cannot be favorable to laws made for the protection of property. When this class becomes numerous, it grows clamorous. It looks on property as its prey and plunder, and is naturally ready, at all times, for violence and revolution.

- Daniel Webster, "First Settlement of New England", speech delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts (December 22, 1820), to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. The Writings and Speeches of Daniel Webster (1903), vol. 1, p. 214.

- Alexander is to a peasant proprietor what Don Juan is to a happily married husband.

- Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace (1972), p. 78.

- Things of the senses are real if considered as perceptible things, but unreal if considered as goods.

- Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace (1972), p. 45.

- The idea of property arises out of the combative instincts of the species. Long before men were men, the ancestral ape was a proprietor. Primitive property is what a beast will fight for. The dog and his bone, the tigress and her lair, the roaring stag and his herd, these are proprietorship blazing. No more nonsensical expression is conceivable in sociology than the term "primitive communism." Society, therefore, is from its beginnings the mitigation of ownership. Ownership in the beast and in the primitive savage was far more intense a thing than it is in the civilized world today. It is rooted more strongly in our instincts than in our reason.

- H.G. Wells, "Pause In Reconstruction And The Dawn Of Modern Socialism", in The Outline of History (1919).

- A 'popular libertarian' might ... feel all that needs to be done to bring the world to justice is to institute the minimal state now, starting as it were from present holdings. On this view, then, libertarianism starts tomorrow, and we take the present possession of property for granted.

- There is, of course, something very problematic about this attitude. Part of the libertarian position involves treating property rights as natural rights, as so as being as important as anything can be. On the libertarian view, the fact that an injustice is old, and, perhaps, difficult to prove, does not make it any less of an injustice. Nozick, to his credit, appreciates this, and implies that in all cases we should try to work out what would have happened had the injustice not taken place. If the present state of affairs does not correspond to this hypothetical description, then it should be made to correspond.

- Jonathan Wolff, Robert Nozick: Property, Justice and the Minimal State (1991), p. 106.

- If I take the wages of everyone here, individually it means nothing, but collectively all of the earning power or wages that you earned in one week would make me wealthy. And if I could collect it for a year, I'd be rich beyond dreams. Now, when you see this, and then you stop and consider the wages that were kept back from millions of Black people, not for one year but for three hundred and ten years, you'll see how this country got so rich so fast. And what made the economy as strong as it is today. And all that slave labor that was amassed in unpaid wages, is due someone today. And you're not giving us anything when we say that it's time to collect.

- Malcolm X, "Twenty million black people in prison," in Malcolm X: The Last Speeches, p. 51

- Give a man the secure possession of a bleak rock, and he will turn it into a garden; give him a nine years lease of a garden, and he will convert it into a desert…. The magic of PROPERTY turns sand to gold.

- Arthur Young, journal entries for July 30 and November 7, 1787, Travels…, 2d ed. (1794, reprinted 1970), vol. 1, p. 51, 88.

- Quotes reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, The Dictionary of Legal Quotations (1904), p. 210-212.

- A thing which is not in esse but in apparent expectancy is regarded in law.

- Lord Edward Coke, Case of Sutton's Hospital (1612), 5 Rep. 303.

- The power to regulate the disposal of property after death ought not to extend to doing it in a manner tending to the prejudice of the living.

- Lord Truro, Brownlow v. Egerton (1854), 23 L. J. Rep. Part 5 (N. S.), Ch. 403.

- The Court has of late years been much more ready to decide questions as to interests in futuro than it formerly was.

- Kekeunch, J., In re Freme's Contract (1895), L. R. 2 C. D. [1895], p. 262.

- Rules of property ought to be generally known, and not to be left upon loose notes, which rather serve to confound principles, than to confirm them.

- Lord Mansfield, Goodtitle v. Duke of Chandos (1760), 2 Burr. Part IV., p. 1076.

- Entry is not equivalent to possession.

- Fry, J., Edwick v. Hawkes (1881), L. R. 18 C. D. 203.

- We must not be frighted when a matter of property comes before us by saying it belongs to the Parliament; we must exert the Queen's jurisdiction.

- Holt, C.J., Ashby v. White (1703), Lord Raym. 938.

- I'm convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, militarism and economic exploitation are incapable of being conquered.

- The law is so benignant in this country that it sometimes contradicts itself in order to preserve estates.

- Lord St. Leonards, Brownlow v. Egerton (1854), 23 L. J. Rep. Part 5 (N. S.), Ch. 407.

- Personal property has no locality. … The meaning of that is, not that personal property has no visible locality, but that it is subject to that law which governs the person of the owner. With respect to the disposition of it, with respect to the transmission of it, either by succession or the act of the party, it follows the law of the person. The owner in any country may dispose of personal property. If he dies, it is not the law of the country in which the property is, but the law of the country of which he was a subject, that will regulate the succession.

- Lord Loughborough, Sill v. Worswick (1791), 1 H. Bl. 690.

- Monuments are memorials of great use in questions of descent, and in matters of family interest; decency and propriety likewise require that they should not remain in a state of ruin and decay.

- Sir William Scott, Bardin v. Calcott (1789), 1 Hagg. Con. Rep. 16.

- There is nothing illegal in keeping up a tomb; on the contrary, it is a very laudable thing to do.

- Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley, L.J., In re Tyler, Tyler v. Tyler (1891), L. R. 3 C. D. [1891], p. 258.

- I am afraid that the state of some other noble monuments of the finest Gothic architecture in this kingdom is not very consoling; that they are mouldering and crumbling into ruins. I have heard it observed with grave and serious regret, that no funds have been appropriated for the preservation of them: perhaps a time will come when that which I take to be an error will be corrected, and when it will be found that all the property of the Church is a fund for the sustentation of those fabrics.

- Eyre, C.J., Jefferson v. Bishop of Durham (1797), 2 Bos. & Pull. 129.

- If a man will make a purchase of a chance, he must abide by the consequences.

- Richards, L.C.B., Hitchcock v. Giddings (1817), 4 Price, 135.

- I may use mine own as I will.

- Sir Henry Hobart, 1st Baronet, C.J., Robins v. Barnes (1614), Lord Hobart's Rep. 131.

- I know of no case in which you are to have a judicial proceeding, by which a man is to be deprived of any part of his property, without his having an opportunity of being heard.

- Bayley, B., Capel v. Child (1832), 2 C. & J. 579.

- The superior man loves his soul; the inferior man loves his property.

- Confucius, cited in A Little Book of Aphorisms (New York: 1947), p. 185.

- "None shall be disseised of his freehold" (Magna Charta).

- Quoted by Thomas Denison, Rex. v. Inhabitants of Aythrop Rooding (1756), Burrow (Settlement Cases,), 414; reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, Dictionary of Legal Quotations (1904), p. 99.

Wikiwand in your browser!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.