British costume during the centuries.

The Britons.

The subject of British costume naturally commences with the garments worn by the primitive inhabitants of these Islands, but, as might be anticipated, the necessary particulars for describing the dress of the Ancient Britons are extremely meagre, and even when given are in many parts almost hopelessly obscure.

Of definite descriptions anterior to the date of the first Roman invasion there are practically none extant, and even after Caesar’s two visits the references to such matters as dress and adornments for the person are scanty and unsatisfactory. We know that the constant intercourse between the Southern coast of Britain and the mainland naturally led to a higher degree of civilisation being existent along the southern littoral than in the Midland and Northern districts; and thus, while the inhabitants of Trent enjoyed the full benefit of that intercourse, the dwellers of Strath-Clyde were still plunged in the depth of barbarism. Arguing from analogy, we should expect the latter to have been clothed in what may be termed man’s primitive attire, namely, the skins of the beasts struck down in the chase, or those of domestic animals slaughtered for food.

This assumption is confirmed by Caesar, who states in his Commentaries, “that those within the country went clad in skins,” while the Southern Britons were clothed like the Gauls.

This condition of things must have lasted for centuries, for even after the Roman occupation we read of the Northern tribes as being but little removed from savages. As we have the authority of Caesar and other ancient writers for asserting that the Southern Britons were similar in manners, customs, and dress to the Gauls, any contemporary knowledge of the latter would naturally apply to the former.

Thus the Gaulish methods for spinning, weaving wool, dressing, and dyeing had been copied by the men of Trent, and, according to the evidence of Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, and Pliny, certain trade secrets in the art of dyeing had also been communicated. The parti-coloured cloth worn by the Gauls was also manufactured in Britain, and appears to have been very characteristic of that period.

It was composed of strands of wool dyed in different colours, and afterwards woven in such a manner that the resulting fabric presented a chequered or parti-coloured appearance, and may have been the prototype of the Scottish plaid. Respecting the dress of Boadicea, who flourished more than a hundred years after the Caesarean invasions, we are informed by Dion Cassius that she wore “a tunic of several colours all in folds, and over it, fastened by a fibula or brooch, a robe of coarse stuff.” This tunic was evidently made of what may be termed the national cloth, and the cloak of common fustian, which all nations emerging from barbarism appear to have the faculty of manufacturing.

The Druidical priests were clad in white voluminous robes reaching to the feet, and consisting of two essential parts, the robe proper and the cloak.

The druidical robe.

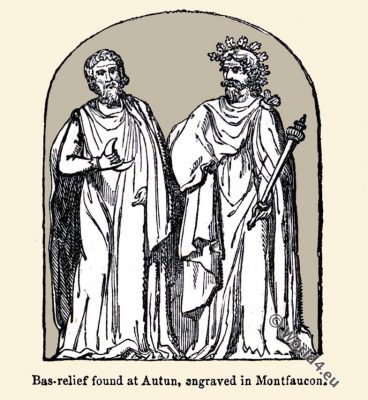

This garment was similar to a sleeveless dressing gown reaching to the feet, but with no collar. We have no knowledge of the material of which it was made, but it was probably of wool, and of special manufacture. A basrelief found at Autun in France represents two Druids (Fig. 1), and from the many folds delineated in each of these robes they were evidently of a soft material.

The druidical cloak.

From the illustration it will be gathered that this was peculiarly ample, inasmuch as some parts reach to the ground. Of the form and dimensions of this garment no data are extant, but practical experience has discovered that if it be cut somewhat like a Roman toga it will give when draped an appearance very similar to that shown in the figure.

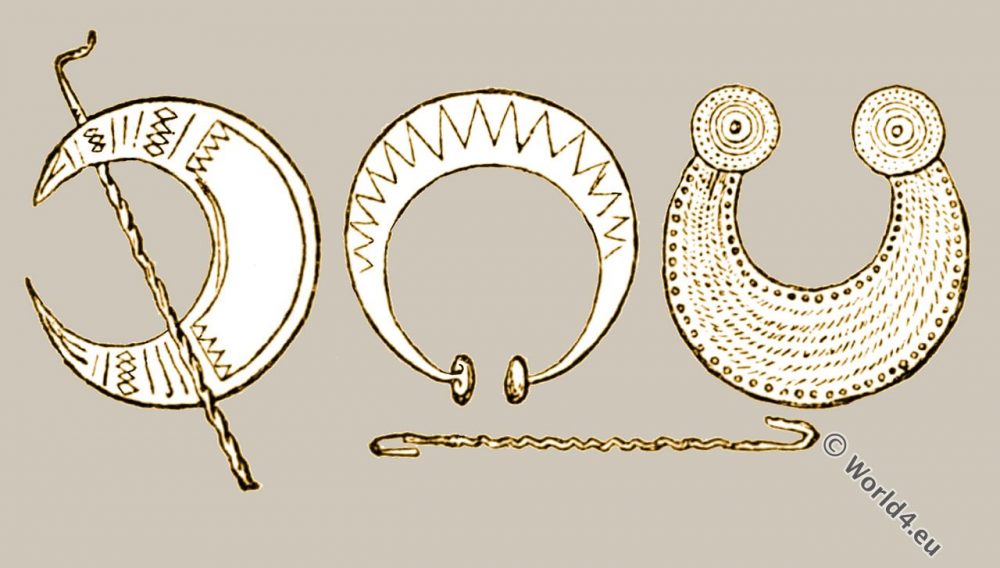

The Druid upon the right is crowned with an oak garland and bears a sceptre; while the one upon the left carries a sacred symbol, the crescent, in his hand. At important ceremonials the Arch-Druid wore a torque or breastplate of a peculiar shape (shown in Fig. 2). The broad lower portion rested upon the chest, and the twocbosses reached on either side to the ears, while upon his head a tiara was worn with diverging rays.

These ornaments were all of gold, and engraved. Respecting the minor priestly orders, the Bards or Singers were habited similarly to the Druids, but in cloth of a sky-blue colour, symbolical of peace. The Ovates, a class professing erudition, were in green, a colour signifying learning. The lowest order of priests or novitiates wore garments of the three colours combined, presumably spots of colour on a white ground.

Civil dress: The men.

The Tunic

The men were habited in a loose-fitting sleeveless tunic, confined at the waist by a belt. Diodorus tells us the Belgic Gauls wore dyed tunics beflowered with all manner of colours, and possibly the Britons may have imitated them. The tunic partly covered the braccae, or trousers, an article of apparel by which all barbaric nations seem to have been distinguished from the Romans. They reached from the waist to the feet, and were either close fitting or loose; if the latter, they were partly confined by bandages passed round the limb at wide intervals. By the use of the term “braccas,” signifying spotted, we may infer that these garments were fashioned from the native cloth, the predominating colour in which was red.

The Sagum

The Sagum was a cloak dyed blue or black, which had superseded the skins still worn by the inhabitants of the interior. The hair was long, and fell in curls down the back; the face was clean shaven, except for the moustache, which was apparently cultivated to its utmost extent, and occasionally reached to the chest. Probably no covering for the head was in use.

The woman dress

The dress of the women consisted of a long loose-fitting sleeveless garment, confined at the waist, over which was worn a cloak or skin, the head as a rule being left uncovered. With respect to the inhabitants of the interior, we can only surmise that they were dressed in skins, and consequently no definite fashions prevailed.

A national characteristic appears to have been the staining of the skin with woad, which is referred to by many ancient writers. From some we should gather that this was a system of tattooing similar to that practised by the Maori, while others infer that the whole skin was stained with the colour so as to give a bluish-green appearance.

Both Herodotus and Isidorus concur in stating that the skin was punctured by needles and the colour afterwards rubbed in. Pliny asserts that this was done during infancy by the British wives and nurses. We may therefore safely assume that the Britons carried indelible designs upon their bodies, which were calculated to add to their ferocious aspect in war. The articles of personal adornment consisted of armlets, bracelets, rings, collars, and necklaces of twisted wire, made of gold, silver, and the commoner metals and alloys.

Source: British costume during XIX centuries (Civil and Ecclesiastical) by Mrs. Charles H. Ashdown. Lecturer upon costume and mediaeval head-dresses. Expert adviser upon costume to several of the great pageants, ect. Published by Thomas Nelson and Sons LTD, London.

Related

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.