Gabor Maté: Founder of Compassionate Inquiry

“Our birthright as human beings is to be happy, and the addict just wants to be a human being.”

Dr. Gabor Maté is a Canadian physician, public speaker, best-selling author, and Jewish Holocaust survivor.

His ideas have revolutionized the way we look at chronic issues, including addiction, autoimmune disease, ADHD, and depression. The core of this philosophy suggests that childhood trauma causes us to lose connection with the self. This disconnect brings many consequences — from narcissistic or abusive tendencies to pessimism, addiction, and depression.

He argues that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can lead to physical illness as well — including Alzheimer’s disease, autoimmunity, ADHD, and much more.

But there’s good news. There may be a way to fix it, regardless of your age or how disconnected you are.

In this article, we’ll summarize Dr. Gabor Maté’s ideas on trauma, addiction, and the unconscious. We’ll also explore how he uses psychedelics with his flavor of psychotherapy and why he believes all drugs should be decriminalized.

| Birth & Death | 1944 – Present |

| Personality Type | INFJ | 9w1 |

| Occupation | Medical Doctor, Author, Public Speaker |

| Nationality | Hungarian-Canadian |

The Life of Gabor Maté

Gabor Maté was born into a Jewish family on January 6, 1944, in Budapest, Hungary.

Just two months after he was born, the Nazis occupied Hungary and began systematically exterminating the Jewish population that lived there.

It was a terrifying time. His father was sent to a Nazi labor camp, and both his maternal grandparents were killed in Auschwitz.

Maté often refers to a story where his mother called the local doctor because her newborn child was constantly crying. The doctor responded by saying that “right now, all my Jewish babies are crying.” This statement was an indication of how scared Jewish families were, which was being felt by the children who pay close attention to the way their parents are acting.

His mother was soon forced to leave baby Gabor in the hands of a stranger in an attempt to protect him from being captured.

His mother’s fear for both her life and the life of her child, as well as the sense of abandonment when his mother left him under the care of someone else, significantly affected Gabor. This later becomes one of the fundamental aspects of his philosophy on how childhood trauma leads to unconscious behaviors and addictions.

Fortunately, Gabor and his immediate family were spared. The war ended, and they emigrated to Canada in 1956 when he was 12 years old.

Career & Education

Maté earned a BA from the University of British Columbia in 1969 and eventually returned to get his MD in general family practice in 1977.

For the next 40 years, Maté worked as a family doctor in Vancouver, Canada.

He was the medical coordinator of the Palliative Care Unit at Vancouver Hospital, a staff physician at Portland Hotel Society, and worked in harm reduction clinics in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

The Downtown Eastside of Vancouver is a 15-block strip in one of Vancouver’s oldest neighborhoods. It’s a place nearly 7000 homeless people call home and one of the most concentrated areas of open drug use, addiction, sex work, and mental illness in North America.

Gabor was first publicized when he defended the work of Insite — Canada’s first supervised injection site and one of only 90 in the world. It’s a place where people can source clean needles and inject themselves under the supervision of medical staff. Insite was designed to be a model for harm reduction with the goal of reducing the number of overdose deaths and transmission of HIV and other blood-borne diseases.

Despite the onslaught of several politicians arguing the project was “unethical,” it’s proven largely successful. Over the past ten years, health officials have reported a 35% reduction in overdose deaths. Reports have also shown that 30% of regular Insite users end up seeking treatment for their addiction.

Gabor publicly defended the role of Insite in removing the marginalization of drug addicts, which only further pushes them to turn to drugs in an attempt to soothe the pain of a reality they find unbearable. This concept later formed the basis of his philosophy on the cause of drug addiction.

Maté believes addiction itself isn’t the issue — it’s merely an attempt to solve the underlying issue. You can read more about Gabor’s stance on safe injection sites on his website.

What is Gabor Maté’s Philosophy?

Gabor lived unconsciously for most of his life. He suffered lifelong bouts of depression, anxiety, various forms of addiction, and obsessive tendencies. He worked hard but neglected both the needs of his family and himself.

It was only later in life, sometime in his late 40s or early 50s, that Gabor began uncovering the source of his imbalance. After working with thousands of people in palliative care and in marginalized and traumatized populations, he began seeing a pattern.

The essence of his philosophy is this:

We have a true self, but we’ve lost contact with it. This happens because of traumas experienced in our childhood.

The good news is that we can reconnect with it and feel better.

This philosophy suggests that childhood trauma is the basis for all human suffering. As a child, the basic human need that drives all of human nature is to connect with others (our parents), with ourselves, and with our environment.

Maté believes that a child’s defense mechanism to trauma is to sever her ability to make these connections. It’s an act of survival while going through experiences where acting authentically may lead to further harm (such as fighting back, speaking up, or crying).

This is because, for a child, it’s safer to cut themselves off from feelings than to try and defend themselves through physical force. A child has almost no control over their experience, and therefore the only way to stop the pain is to cut themselves off from the way their body feels.

When this happens, it remains with us for long periods of time. We repress memories of the events, but the disconnection remains — affecting all aspects of our lives. He believes adverse childhood experiences or ACEs are largely responsible for mental illness, addiction, ADHD, and physical illnesses such as autoimmune disease and cancer.

Compassionate Enquiry

Maté developed a psychotherapeutic model called Compassionate Inquiry, which is designed to reveal the source of the disconnection we developed as a child. It seeks to look behind the persona — which is our outward appearance that consists of all the features we wish to present to the world. Through a method of compassionate, non-judgemental questioning, this approach aims to identify the unconscious dynamics that control how we think, feel and act.

A lot of these concepts mirror the ideas of Carl Jung — essentially seeking to find the shadow self, which contains the parts we suppress or keep hidden from view, yet have a substantial unconscious influence on who we are.

One of the key differentiators of Compassionate Inquiry from other psychotherapeutic approaches is to focus less on the past and more on the present. There’s nothing we can do to change what happened. It happened. But we can focus on healing the open wound of trauma in the present moment.

Maté believes that understanding what happened in the past can help us understand what’s going on in the present, but we ought not to dwell on it.

This is where the compassionate part comes in. The first step of identifying the cause of our disconnection is to forgive ourselves. We often feel shame, guilt, or regret for our actions. Maybe we hurt someone we love or wasted our time doing things that didn’t give us the outcome we wanted. Compassionate Inquiry teaches that instead of asking “what the hell is wrong with me?!” it should be more of a ponderous “hmm, I wonder what caused me to respond that way?”

Childhood Trauma

We often think of trauma as an event that caused us physical or psychological harm. Maté teaches that trauma isn’t the event but the wound that’s sustained as a result.

When we’re children, we don’t have the ability to resist the damage from harmful experiences, which leads to an unhealed wound or scar tissue — this is the trauma.

The cause of the trauma is what Gabor calls an Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE). Here are a few examples:

- A child being abused

- Violence in the family

- A jailed or absent parent

- Extreme stress or poverty

- A resentful divorce

- Addiction in the family

As children, we believe the moment is permanent. When a child feels hungry, they cry and scream as if they’ll never be able to eat food again.

The same is true when experiencing an ACE. The child believes the pain and discomfort from the event will go on forever and so takes action to protect themselves internally. The child has not yet developed the tools to stop the event by removing themselves from the situation, fighting back, or speaking out against it. Instead, they sever the connection between the body (sensory) and the mind.

This disconnection is what causes trauma that can last a lifetime if the effort isn’t made to heal it.

There are two main ways a child trauma manifests in a child after experiencing an ACE:

1. Shame

Children are narcissists — they think everything is about them. When something goes wrong, even if it isn’t their problem, they believe it’s their fault.

“Bad things are happening so I must be a bad person.”

This causes them to feel shame which Gabor considers “the most caustic aspect of trauma.”

2. Powerlessness

Children have very little power over their situation. When something bad happens, our gut instinct is to run away. But a child may not be able to fight or run away, and attempting to do so may be more dangerous than staying. In order to protect the organism from what our gut instincts are telling us, the mind disconnects itself from those gut instincts.

The Collective Unconscious & Generational Trauma

Gabor recognizes the concept of the collective psyche (not unlike Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious).

Generational trauma is passed down to us from our parents, which was passed down through their parents.

The only way of breaking the cycle is to wake up and become aware of the impact our own early childhood experiences had on our lives and take measures to break the cycle as it’s passed down to our children and grandchildren.

Examples of this include the Native Americans in Canada (and elsewhere in North America). When European settlers began colonizing the region, they would separate Native American children from their families, brutalize them, and repress their culture and instinctual behavior.

This has left a lasting mark on the Native American communities today — which is riddled with violence, addiction, and mental illness. When someone is traumatized as a child, the scars left on their unconscious mind cause them to exert a similar form of trauma to their children. This is passed down the line for generations.

How Does Childhood Trauma Manifest In Our Lives?

Gabor has identified a few ways childhood trauma can influence our daily lives in ways we’re unaware of. There are four points here, each one intentionally vague.

How trauma manifests for each person is very different:

- A compulsive need to support others and ignore their own

- Identifies with duty and responsibility

- Repression of healthy aggression (or anger)

- Not wanting to disappoint other people

So What Do We Do About It?

In answering this question, Maté often explains what he has planned for his epitaph after he dies:

“It [life] was a lot more work than I anticipated.”

Repairing the scars childhood trauma leaves within our unconscious involves a lot of work.

He once stated that “It’s a lot of work to wake up as a human being. It’s easier to stay asleep than to wake up.”

In Maté’s philosophy, self-awareness is key. Once we understand how and why we feel a certain way, we can uncover the childhood traumas that led us to this point. Only then can we begin to strip their unconscious influence over our thoughts, emotions, and perceptions.

In essence, the idea is to notice it, acknowledge it & recognize it.

This process inevitably involves a lot of pain. The source of these issues is something we’ve been programmed to avoid for our entire lives. That is until something forces us to face the fact that our lives aren’t working out the way they should.

Childhood Trauma & Addiction

Gabor Maté has written extensively on the topic of addiction, and the role childhood trauma plays in the pathophysiology of addiction. He published his ideas in his book In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts.

There’s a lot to cover here, so we’re only going to cover the distilled version of this philosophy. I encourage you to read Gabor’s book or check out some of the talks posted at the bottom of this article for more information.

First, how does Gabor Maté define addiction?

He describes addiction as a behavior where a person craves something in search of temporary pleasure or relief from something — but suffers negative consequences as a result and is unable to give up despite the harm it’s causing them or the people around them.

Maté’s ideas about addiction break free from the norm — arguing that addiction is not a genetic disease and that there’s no such thing as an “addictive personality.”

Addiction itself is not the problem — rather, it’s an attempt to solve a problem.

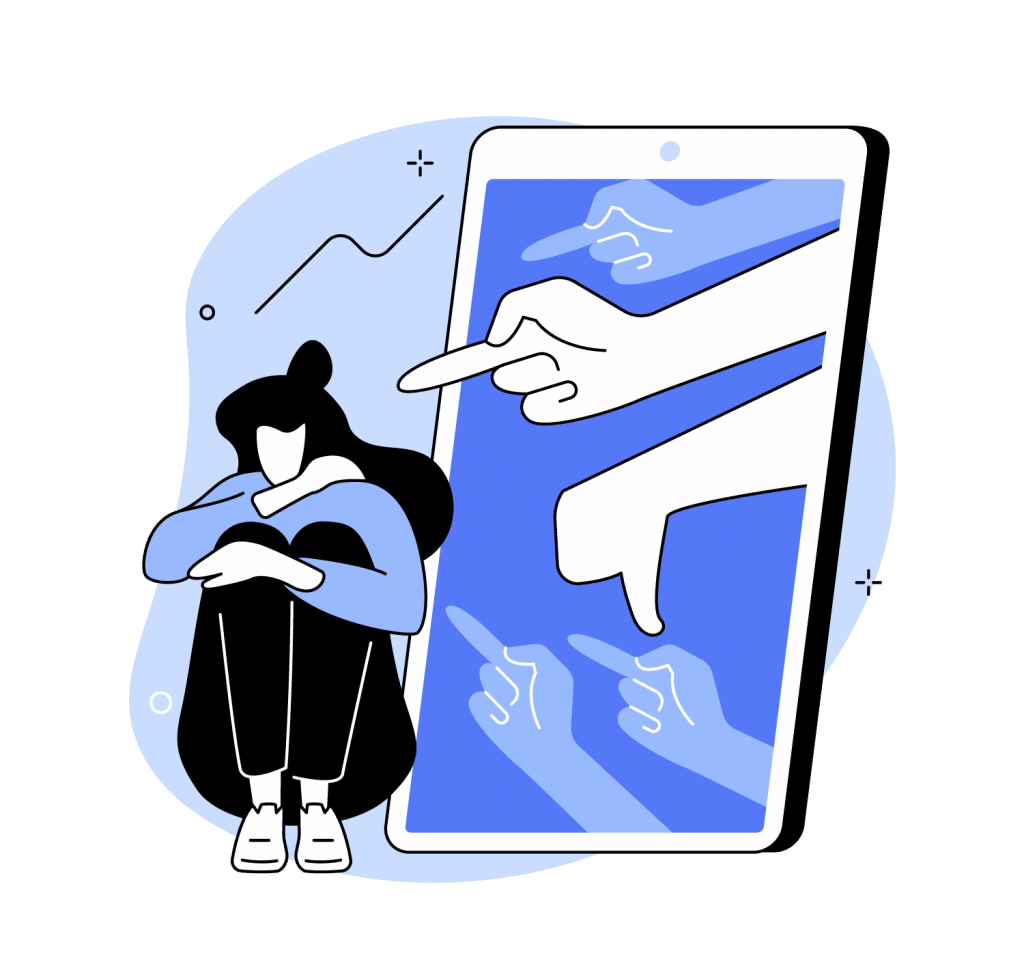

He believes addiction to drugs, gambling, sex, shopping, or anything else comes from an attempt to soothe discomfort and solve a problem they’re unable to solve through other means.

Nobody chooses to be addicted to drugs — it’s not a choice people consciously make. People use drugs to find temporary relief from something. They seek this relief through external factors because there’s a deep disconnection with their true self. As we’ve touched on before, the core cause of this disconnection is childhood trauma.

Gabor doesn’t ask the question, “what substance are you addicted to” because this is irrelevant. He’s more interested in asking about “what does the drug do for you.” He wants to know what the drug is offering a release from in order to help the user identify what needs their body has that aren’t being met or what unconscious force they’re repressing through the use of drugs.

Related: How Psychedelics Are Reinventing Addiction Therapy.

Maté & Decriminalization

Maté is a proponent of the decriminalization of all drugs.

He argues the “war on drugs” only serves to punish people for having been abused. That pushes people deeper into the grasp of addiction — rather than extending them a helping hand to pull themselves out of it.

When we look at addiction as a physical disease, we don’t acknowledge the lived experience of the individual. The behaviors are just symptoms, they are not the core.”

His influence can be seen in some of the policies we’ve seen in Vancouver — which recently moved to decriminalize all drugs in November 2020.

Suggested Reading: List of Legal Psychoactive Substances Around the World.

Gabor Maté on Psychedelics

Gabor is an outspoken advocate for the use of psychedelics as a source of healing. He admits there’s a bit of a negative connotation about the use of psychedelics because some people use them to escape from reality. He’s made a case against this by suggesting the complete opposite — that they help us become more connected with reality. It all comes down to intention, context, and integration.

He stated that “psychedelics allow us to experience our brains from a different angle. When combined with a trauma-informed approach and the proper intention and guidance, psychedelics can be a powerful tool for healing.”

The basis of this idea is that our personality is shaped by the traumas and stresses we experience throughout our lives. Psychedelics dissolve the personality, allowing us to see the scars under the surface that surround our personality.

This idea mirrors the concepts suggested by Carl Jung and the process of integrating our shadow. The shadow refers to the parts we refuse to accept about ourselves and therefore seek to suppress. There are many reasons for suppressing traits like anger, greed, jealousy, or lust. Gabor’s approach focuses primarily on the traits we suppress because of events that happened when we were children.

Gabor Maté was first introduced to ayahuasca in 2010 after writing his book, In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts. He was on a book tour speaking about the book and kept getting questions about what he thought about ayahuasca and addiction. At the time, he didn’t know anything but was asked this question enough times to look into it and eventually take part in a ceremony himself.

After trying ayahuasca, he instantly connected the dots as to what role this traditional Amazonian medicine could offer in healing addiction.

Maté connected with a Shipibo Shaman from the Peruvian Amazon and began running retreats on Vancouver Island shortly after.

A local Native American group asked Maté if he would run one of these retreats for a few members of their group. He obliged and even allowed a group from the University of Victoria to study the outcome of the retreat.

It was the result of this event that Health Canada asked him to stop his work in studying psychedelics without approval or risk prosecution. While the studies came to a stop, the retreats have continued.

Gabor Maté Quotes

Maté’s quotes are often insightful and thought-provoking, and they offer a unique perspective on addiction, trauma, psychedelics, and the brain.

Here are a few of his most famous quotes:

On Consciousness & Persona

Once a student’s eyes are open, instructors appear everywhere. Everything can teach us.

Our most painful emotions point to our greatest possibilities, to where our authentic nature is hidden. People whom we judge are our mirrors. People who judge us call forth our courage to respect our own truth.

Compassion for ourselves supports our compassion for others. They may do the same for us. Healing occurs in a sacred place located within us all: “When you know yourselves, then you will be known.

What we call the personality is often a jumble of genuine traits and adopted coping styles that do not reflect our true self at all but the loss of it.

When I am sharply judgmental of any other person, it’s because I sense or see reflected in them some aspect of myself that I don’t want to acknowledge.

No society can understand itself without looking at its shadow side.

Strong convictions do not necessarily signal a powerful sense of self: very often quite the opposite. Intensely held beliefs may be no more than a person’s unconscious effort to build a sense of self to fill what, underneath, is experienced as a vacuum.

Couples choose each other with an unerring instinct for finding the very person who will exactly match their own level of unconscious anxieties and mirror their own dysfunctions and who will trigger for them all their unresolved emotional pain.

Shame is the deepest of the “negative emotions,” a feeling we will do almost anything to avoid. Unfortunately, our abiding fear of shame impairs our ability to see reality.

Much of what we call personality is not a fixed set of traits, only coping mechanisms a person acquired in childhood.

On Addiction

Our birthright as human beings is to be happy, and the addict just wants to be a human being.

It is impossible to understand addiction without asking what relief the addict finds, or hopes to find, in the drug or the addictive behavior.

The attempt to escape from pain is what creates more pain.

Not why the addiction but why the pain.

Passion creates, addiction consumes.

Boredom, rooted in a fundamental discomfort with the self, is one of the least tolerable mental states.

Gabor Maté Books

- Scattered Minds: A New Look at the Origins and Healing of Attention Disorder (2000)

- When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress (2003)

- Hold On To Your Kids: Why Parents Need to Matter More Than Peers (2004)

- In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction (2010)

- The Myth of Normal: Illness and Health in an Insane Culture (Coming Late 2021)

Best Gabor Maté Lectures

Dr. Gabor Maté has been giving lectures and teaching his method of Compassionate Inquiry for over a decade. I’ve watched dozens of hours of Maté speaking and collected what I believe to be some of his best interviews and talks:

Gabor Maté on Addiction

How Childhood Trauma Leads to Addiction (After Skool)

Gabor Maté on The Tim Ferriss Show

How Emotions Affect Cognitive Function

When The Body Says no

Cannabis & Addiction

Final Thoughts: Who is Gabor Maté?

There are few people as eloquent and concise as Gabor Maté when discussing topics like the source of human unhappiness and addiction.

Maté combines his own experience with childhood trauma and personal pain and discomfort with the philosophies of Carl Jung, Friedrich Nietzsche, and others to form what he calls Compassionate Inquiry.

Maté believes that as children, the mind learns to disconnect itself from the body in order to protect itself from physical harm or abuse. The lasting impact this experience has on our psyche manifests in ways completely outside our conscious thought but can lead us to live lives we’re unhappy with — often perpetuating the cycle bypassing this trauma down to future generations.

Through a process of applying compassion and reconnecting with the self — often with the help of psychedelics, we’re able to identify the source of the disconnect and take actions to reconnect.