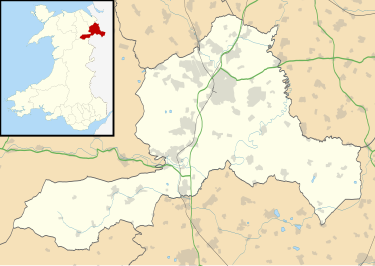

Wrexham County Borough (Welsh: Bwrdeistref Sirol Wrecsam) is a county borough, with city status,[3] in the north-east of Wales. It borders the English ceremonial counties of Cheshire and Shropshire to the east and south-east respectively along the England–Wales border, Powys to the south-west, Denbighshire to the west and Flintshire to the north-west. The city of Wrexham is the administrative centre. The county borough is part of the preserved county of Clwyd.

Wrexham County Borough

Bwrdeistref Sirol Wrecsam (Welsh) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto(s): | |

Wrexham shown within Wales | |

| Coordinates: 53°03′N 3°00′W / 53.05°N 3.00°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Wales |

| Preserved county | Clwyd |

| Formation of County Borough | 1 April 1996 |

| Administrative HQ | Guildhall |

| Government | |

| • Type | Principal council |

| • Body | Wrexham County Borough Council |

| • Control | No overall control |

| • MPs | 3 MPs

|

| • MSs | 2 MSs

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 195 sq mi (504 km2) |

| • Rank | 10th |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

| • Total | 135,394 |

| • Rank | 10th |

| • Density | 700/sq mi (269/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-WRX |

| GSS code | W06000006 |

| Website | wrexham |

The county borough has an area of 193 square miles (500 km2) and a population of 136,055. The north of the county borough is relatively urbanised and centred on Wrexham, with a population of 44,785, its industrial estate and several outlying villages, such as Brynteg and Gwersyllt. To the north east is the border village of Holt, while to the south of Wrexham, Rhosllanerchrugog, Ruabon, Acrefair and Cefn Mawr are the main urban villages. Further south again is the town of Chirk, near the border with Shropshire, while the Ceiriog Valley to the south-east and English Maelor to the south-west of the county borough are rural. The county borough was historically split between Denbighshire and Flintshire, with it all later being part of the county of Clwyd.

The county borough is flat in the east and hilly in the west. The long salient to the south-west incorporates most of the Ceiriog Valley and includes part of the Berwyn range. The River Ceiriog forms part of the Shropshire border in its lower stages before meeting the Dee east of Chirk. The Dee itself enters the county borough near Cefn Mawr and flows east and then north-east toward Cheshire, creating a wide plain. It forms part of the border before fully entering England at the county borough's north-east corner. The north-west of the county borough, down to Chirk, is part of the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB, and includes the Ruabon Moors uplands.

Wrexham includes the remains of two significant medieval castles: Chirk, which is now a country house, and Holt, of which only fragments remain. The county borough has a strong industrial history; a notable early business is Bersham Ironworks, in the Clywedog Valley, which operated between 1715 and 1812 and pioneered cannon manufacture. The area is part of the North Wales Coalfield and significant mining took place in the nineteenth century. Tanning and brewing were also significant industries. The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct near Cefn Mawr is an important surviving piece of early industrial infrastructure and has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The contemporary economy of the county borough has diversified into industries such as engineering, pharmaceuticals, electronics, and food processing, with agriculture dominant in the south-east and south-west. The county borough also contains Wrexham University, one of Wales' three Roman Catholic cathedrals, Wrexham Industrial Estate and the UK's largest prison, HMP Berwyn.

History

editBorough status

editIn 1848, concerns over the sanitary conditions, in particular the threat of cholera,[4][5] in the growing town of Wrexham, led to locals launching a petition in February 1857 for the town to be incorporated. In September 1857, the town was granted a charter,[4][6] spanning the two townships of the town, Wrexham Abbot and Wrexham Regis,[5] as well as part of Esclusham Below, and forming the borough of Wrexham, with a borough council (a corporation) and mayor under the terms of the Municipal Corporations Act 1835.[7][8][9] During incorporation the town was also given a coat of arms.[10]

Between 1894 and 1974, as part of Denbighshire; the remaining civil parishes surrounding but excluding the town were part of the Wrexham Rural District, civil parishes in the Maelor region were part of the Overton Rural District, renamed Maelor Rural District in 1953. Whereas civil parishes in Chirk and the Ceiriog Valley were from 1894 part of either the Chirk Rural District or Llansillin Rural District, until they were merged into the Ceiriog Rural District in 1935, and abolished in 1974 to become part of Clwyd's Glyndŵr district.[11]

The Local Government Act 1958 formed the Local Government Commission for Wales tasked to review the potential reform of local government in Wales. In their 1963 report, the commission rejected proposals for the establishment of Wrexham as a county borough.[12]

Status within Clwyd, then as County Borough

editThe borough of Wrexham, Wrexham Rural District (except Llangollen Rural and Llantysilio), Marford and Hoseley (from Hawarden Rural District, Flintshire) and the neighbouring Flintshire exclave of the Maelor Rural District, were abolished in 1974, all being absorbed into the Wrexham Maelor district of the then administrative county of Clwyd.[11][13] Chirk and the Ceiriog Valley were part of the Glyndŵr district.

Clwyd itself was abolished in 1996 as an administrative county, becoming a preserved county for ceremonial lieutenancy purposes.[14]

Wrexham was established as a county borough (a principal area; same powers as counties in Wales) in 1996, containing all of the former Clwyd district of Wrexham Maelor, and the communities of Chirk, Glyntraian, Llansantffraid Glyn Ceiriog and Ceiriog Ucha from the Glyndŵr district.[10][14]

Following formation in 1996, there were discussions over the boundary between the newly created principal areas of Denbighshire and Wrexham County Borough, in particular over the lower Dee Valley and Llangollen area. Llangollen, Llangollen Rural and Llantysillio were all considered to potentially all or partly become part of Wrexham County Borough. Referendums were held in the communities, with the community of Llangollen Rural, originally in Denbighshire in 1996, transferred to Wrexham County Borough in 1997 through the enacting of "The Denbighshire and Wrexham (Areas) Order 1996" on 1 April 1997.[15][16][17]

Referendums by Llangollen Town Council were held in 1993 and 2000, with the latter resulting in a narrow majority of nineteen votes for staying in Denbighshire, and the Welsh Assembly accepting the result by confirming the boundaries in 2002.[18]

On 1 September 2022, the county borough was awarded city status on behalf of Wrexham's application.[3]

Geography

editWrexham County Borough is a landlocked principal area in Wales. It is a "border county" in the Welsh Marches border region. It is bordered by the English counties of Cheshire to the east and Shropshire to the south and south-east, and the Welsh counties of Flintshire to the north, Denbighshire to the west, and Powys to the south-west.

Parts of the Berwyn range and Maesyrchen Mountains, some part of the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty since 2011, border the county borough to its west.[19] To the east across the River Dee, the county borough meets the Cheshire Plain.[20]

The county borough's boundaries can be characterised by two protrusions from the largely contiguous borders surrounding the city of Wrexham, sometimes defined as Maelor Gymraeg (meaning "Welsh Maelor"). To the south-east of the city, across the River Dee, the English Maelor (Welsh: Maelor Saesneg; a former part of Historic Flintshire) extends to almost meet the English town of Whitchurch, Shropshire and Fenn's Moss.[21] To the south-west, a large salient of the county borough to the west of Chirk, along the River Ceiriog and the surrounding Ceiriog Valley meets the Berwyn range and the Powys border. The highest point in the county borough is Craig Berwyn, rising 790 metres on the Wrexham-Powys border in the Berwyn range.[citation needed]

There are two upland areas in the county borough, both located on its western edge. The Berwyn mountains, and the Ruabon and Esclusham Mountains. The Berwyns and Ruabon Mountain are designated SSSIs and SACs.[22]

The county borough is within the preserved county of Clwyd, and between 1974 and 1996 as part of the then administrative county of Clwyd, the present-day county borough was divided into the districts of Wrexham Maelor and Glyndŵr. Before Clwyd's establishment in 1974, the modern-day county borough was part of the historic counties of Denbighshire (spanning most of the modern-day county borough; including Wrexham), and Flintshire (the English Maelor exclave).[citation needed]

Offa's and Wat's Dyke, and their respective pathways (Offa's Dyke Path,[23] and Wat's Dyke Way)[24] pass through the county borough. Other pathways include the Dee Way Walk,[25] and Maelor Way.[26] The Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses National Nature Reserve is located in the south-east of the county borough along the Wrexham-Shropshire border.[27]

The county borough is largely urban and industrial surrounding Wrexham, but largely rural for the rest of the county borough, with areas of farmland and rural estates. Woodlands cover 9.4% of the county borough, lower than the national average of 14%.[28]

The main settlement of the county borough is the city of Wrexham with 44,785 inhabitants in 2021.[29] Its neighbouring villages include Gwersyllt, Rhostyllen, Brymbo, Bradley and New Broughton. These, along with Wrexham, formed Wales' fourth largest urban area with 65,692 inhabitants in 2011.[30] The sole other town in the county borough is Chirk. The main villages of the county borough are Rhosllanerchrugog, Ruabon, Cefn Mawr, Coedpoeth, Gresford, Llay, Holt, Llansantffraid Glyn Ceiriog, Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog, Bangor-on-Dee and Marchwiel.

Rhosllanerchrugog's built-up area extends to Ruabon, Cefn Mawr and Acrefair, with a total population of 25,362 in 2011.[31]

There are 69 sq mi (180 km2) of principal rivers in the county borough, including the River Dee, Ceiriog, Alyn and Clywedog, as well as important streams.[22]

The River Dee is the main river in the county borough, flowing from Denbighshire in the west into the county borough passing Froncysyllte, under Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, and passing Chirk, until it flows north-east towards England, cutting off the county borough's south-east salient of Maelor Saesneg (meaning "English Maelor") and later forming part of the border between Wales and England. River Alyn, a tributary of the Dee, flows in the north of the county borough.[citation needed]

There are various small lakes in the county borough. While there are 3000 ponds, mainly concentrated in Hanmer, Maelor and Overton.[22]

There is a veteran tree, said to be over 1,000 years old, near Chirk, known as the Oak at the Gate of the Dead.[32] There are also some caves under Esclusham Mountain to the west of the county borough, with caves such as: Ogof Dydd Byraf and Ogof Llyn Parc.

Country parks

editThere are eleven urban and country parks in the county borough operated by Wrexham council. These include all the country parks, three urban parks in Wrexham and Ponciau, as well as the Nant Mill Visitor Centre and Brynkinalt Park.[33] The seven country parks[34] in the county borough are:[35] Alyn Waters,[36] Bonc-yr-Hafod,[37] Erddig Park,[38] Minera Leadmines,[39] Moss Valley,[40] Stryt Las Park, and Tŷ Mawr.[28][41][42]

There are two country house estates with significant areas of parkland and woodland, those being at Brynkinalt (near Chirk; with the Brynkinalt Park; also known as Chirk Green being council-operated),[43] and at Erddig (National Trust-operated; south of Wrexham).[44][45] Iscoyd Park in Maelor Saesneg also boasts some parkland.

Nant Mill hosts a Visitor Centre on the Clywedog Trail and is surrounded by woodland,[46] whereas Stryt Las Park between Rhos and Johnstown hosts grassland, woodland and ponds.[47] Both are operated by the council.

Wrexham city has two main city parks, Bellevue Park,[48][49] and Acton Park,[50][49] there is also a city centre green in-front of the council's Guildhall. Rhosllanerchrugog and Ponciau have Ponciau Banks Park as their urban park.[51][33]

87% of the population in the county borough is within two miles of the main parks in the county borough.[28][33] The remaining areas are already largely rural, in particular the Ceiriog valley and English Maelor.[33]

Clywedog Trail spans for 5.5 miles (8.9 km) along the River Clywedog, from the Minera Lead Mines to King's Mills.[52] Offa's Dyke Path passes through the county borough.[53]

Bonc-yr-Hafod and Stryt Las are both part of the Stryt Las a'r Hafod Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).[33][54][55]

Politics and local government

editThe principal area (styled as a "county borough") is governed by Wrexham County Borough Council, a Welsh local authority principal council. Most offices of the council are situated within Wrexham city centre, around Llwyn Isaf and Chester Street. The headquarters of the council's Chief Executive is at the Guildhall (Welsh: Neuadd y Dref; lit. 'Town hall') in Wrexham.[49][56] From May 2022, there are forty-nine electoral wards for the council, with seven having two councillors.

The most recent Wrexham County Borough election on 5 May 2022,[57] resulted in independent politicians maintaining their position as the largest group with 23 members but falling short of a majority, leaving the council in no overall control.[58] Since 2017,[59] the principal council has been operated by a coalition of local independents, the "Wrexham Independents" group and the Conservatives.[60] Following the 2022 election, on 11 May 2022, local independents and the separately organised "Wrexham Independents" merged into a 21-member[i] "Independent Group", and formed a coalition with the Conservatives again for another five-year term.[61] The next election for the council is due for 6 May 2027,[62] as part of the next Welsh local elections.

The county borough was formed on 1 April 1996 following the enactment of the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, containing the district of Wrexham Maelor and some communities of Glyndŵr, namely Chirk, Glyntraian, Llansantffraid Glyn Ceiriog, and Ceiriog Ucha, and later Llangollen Rural in 1997.[14] Borough status was inherited from the town of Wrexham, which was granted to the then town in September 1857.[10]

The area includes a portion of the eastern half of the historic county of Denbighshire and two exclaves of historic Flintshire: English Maelor and the parish of Marford and Hoseley.

The county borough is in the East Wales ITL 2 (formerly NUTS 2) and "Flintshire and Wrexham" ITL 3 (formerly NUTS 3) statistical regions by the UK's Office for National Statistics (and until 2020 Eurostat).[63] It is regarded to be in the North East Wales and North Wales non-administrative regions[64][65] (and the associated regional bodies, such as North Wales Economic Ambition Board,[66] North Wales Police,[67] North Wales Fire and Rescue Service,[68] Tourism Partnership North Wales, and Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board).[69]

In Westminster, from the 2024 United Kingdom general election, Wrexham County Borough is split between three UK Parliament constituencies, Clwyd East, Montgomeryshire and Glyndŵr, and Wrexham.[70][71]

In the Senedd (Welsh Parliament), Wrexham County Borough is split into two Senedd constituencies, Clwyd South and Wrexham, each electing a Member of the Senedd (MS) each. The county borough is also part of the North Wales Senedd region which elects a further four regional members.[72]

Polling done by UnHerd in 2019, showed that of those polled 54% of the county borough supported the continued reign of the British Monarch, compared to 23% and 21% opposed, and 23% and 25% do not know, in the Wrexham and Clwyd South constituencies respectively.[73]

In the 2016 National Survey for Wales, only 45.9% of the population agreed or strongly agreed that Wrexham County Borough Council provides quality services, below the Welsh average of 59.3%.[28]

Local recent political history

editOn 23 June 2016 in the 2016 EU referendum, the county borough voted 59% in favour of Leave.[74]

In the 2019 United Kingdom general election, Conservative candidates won the constituencies of Wrexham and Clwyd South for the first time in their existence.[74][75][76] The constituencies were generally considered to be Labour heartlands part of its "red wall",[77] and were won by Labour in the June 2017 election, as well as previous elections.[78][79][80] In the 2021 Senedd election, Welsh Labour incumbents for the Senedd constituencies of Wrexham and Clwyd South covering the county borough were re-elected.[74][81][82]

In 2021, the council submitted bids for UK City of Culture 2025 on behalf of the county borough although later lost to Bradford, and a separate bid, submitted in December 2021, to award the then town of Wrexham the status of a city for the civic honours awarded for the 2022 Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II, which it later won.[83] It was the only city bid from Wales, and Wrexham has applied for city status three other times, in 2000, 2002 and 2012, with the 2012 bid lost to St Asaph, Denbighshire.[84] City status was awarded to the "County Borough of Wrexham" on behalf of Wrexham on 1 September 2022.[85] In November 2021, a local consulation survey conducted by Wrexham council, reported that 61% of respondents stated that Wrexham does not "deserve" to be a city.[86]

In February 2024, a report from Audit Wales, stated that the council's planning members had a poor relationship with professional officers over planning decisions and the council frequently undermine officers, looking for alternative opinions instead.[87] Audit Wales also criticised the council's failure to adopt its local development plan.[88] In March 2024, The Municipal Journal, stated that an investigation had begun into an allegation of malfeasance in office by Wrexham councillors, with both North Wales Police and the Welsh Government participating in the case.[89]

Westminster members

editWrexham County Borough is located in three constituencies, and their MPs are:[71]

| Constituency | Member of UK Parliament | Political party | First elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clwyd East[ii] | Becky Gittins | Labour | 2024 | |

| Montgomeryshire and Glyndŵr | Steve Witherden | 2024 | ||

| Wrexham | Andrew Ranger | 2024 | ||

Senedd members

edit| Electoral district | Member of the Senedd | Political party | First elected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constituencies | Clwyd South | Ken Skates | Labour | 2011 | |

| Wrexham | Lesley Griffiths | 2007 | |||

| Senedd | North Wales

Regional members of the Senedd |

Carolyn Thomas | 2021 | ||

| Llyr Huws Gruffydd | Plaid Cymru | 2011 | |||

| Mark Isherwood | Conservative | 2003 | |||

| Sam Rowlands | 2021 | ||||

Communities

editElectoral wards

editEconomy and industry

editThe economy of the county borough has changed over the past few decades, from a largely coal-mining focused heavy industrial area, into a high-tech manufacturing, technological and service industry hub.[90]

The main industry is manufacturing with around 20% (18.3% in 2011 census) of employment in the county borough being in the manufacturing sector.[91] The other largest sectors from the 2011 census include: 15.2% in the Wholesale and retail sector (including vehicle repair), 14.6% health sector, 8.9% education, 6.9% construction, 6.0% government and military, 4.9% accommodation and food service, 4.4% administration and support services, 4.3% transport, 3.9% professional, scientific and technical, 2.8% finance and industry, 1.8% IT and 8% other.[92] When classed together the public sector counts for more than a third of jobs in the county borough.[91] 75% of the total land in the county borough is managed by farmers.[28]

Brewing

editHistory

editIn the 19th century, a brewing industry developed in Wrexham town, alongside the then town's existing leather and coal industry.[93][94] The town became a brewing centre due to the town's good underground water supplies near but not of the River Gwenfro.[95][96] The sands and gravels in the surrounding river plain filters groundwater which builds up on the impervious rocks beneath.[96] Wrexham also sits above a faultline, dividing the area into a mineral-rich hard water east suitable for brewing beer, and a soft water west for lager.[96] Many breweries were also set up in the medieval times in the township of Wrexham Abbot which would have had lower taxes than Wrexham Regis, the areas controlled by the Crown.[96] By the 1860s, there were 19 breweries in the town.[95] Many brewers became leading politicians in the town, with two brewers, Thomas Rowland and Peter Walker disagreeing who should be mayor of Wrexham.[95]

Wrexham Lager has been brewed in Wrexham since 1882.[95][97] The brewery produced the first German-brewed lager in the United Kingdom, and was located in Wrexham for the brewing quality of its underground spring water.[98] The lager was reputedly served on board the Titanic, other White Star Line ships and by soldiers during the Siege of Khartoum.[99][100][101] It is also claimed to be the first lager to been exported to countries such as India, South Africa, Australia and various countries in the Americas.[102] The brand started to decline during the World wars, following changing consumer tastes, rationalisation, and the internationalisation of the industry.[102][103] The brewery was bought by Ind Coope & Allsopp, eventually merged into Allied Breweries and later Carlsberg-Tetley.[102] The original brewery located on top of the Gwenfro was closed by Carlsberg in 2000, with all UK-wide production by Carlsberg of the brand ceasing in 2002. The modern brewery, constructed in the late-20th century, was demolished between 2002 and 2003,[103] and was replaced with Wrexham Central Retail Park. The original brewhouse building on Central Road within the now retail park remains as a Grade II listed building.

Another known brewery formerly operating in Wrexham was Soames's Brewery, and what later became Border Breweries. The brewery can be traced back to a minor brewing business operating out of the Nag's Head Public House on Tuttle Street.[104] It was not until 1874 following an acquisition, that "Wrexham Brewery" started to become a major producer. In his 1892 tour, Alfred Barnard described Soames's to have the best beer in Wrexham.[95][105] The Border Breweries company was formed from the merger of Soames Wrexham Brewery, Island Green Brewery and Dorsett Owen in 1931.[105][104] It was purchased by Marston's Brewery in 1984 and closed by Marston's six months later despite stating otherwise.[95][104] Other former breweries include Albion, Cambrian, Eagle, Island Green, and Willow.

Present day

editIn 2011, the Wrexham Lager brand was revived, launched in the Buck House Hotel in Bangor-on-Dee,[106] it later moved to a newly built high-tech microbrewery on St. George's Crescent to the east of Wrexham city centre from the original brewery.[102]

In recent years, the lager has experienced success, with the lager in 2022 announced it will be sold in Aldi stores across Wales and England.[107]

As of April 2022[update], the other microbreweries currently set up in the county borough include: Big Hand Microbrewery (Wrexham Ind. Est.),[108] Magic Dragon Brewery (Plassey),[109] McGivern Ales (Ruabon),[110] and Sandstone Brewery.[111][112]

Red brick

editRuabon to the west of the county borough has a deep history in brick and tile-making. This is owed to its vast amounts of high quality Etruria Marl clay. In the 19th century this clay was the centrepiece for Ruabon's tile and terracotta production on a vast scale, leading the village to be nicknamed "Terracottapolis".[113][114][115] Its former manufacturing speciality the "Ruabon Red Brick" were used in various buildings of the Victorian era, such as the Pierhead Building in Cardiff, Victoria Building of Liverpool University and in the restoration of the Taj Mahal.[99][113] Hafod Brickworks were established near Hafod Colliery in 1878, and a "Red Works" in 1893.[113][116] The bricks contributed to the term "redbrick" in the term "Red brick university". Brick production largely ceased in the 1970s, with production mainly focused on quarry tiles.[113]

Former mining

editIn 1854, there were 26 coal mines operating in the western uplands of Wrexham.[117] The main mines were located at Ruabon, Rhos, Acrefair, Brymbo and Broughton (particularly around the Moss Valley). Mining operations were later concentrated, with larger colleries such as Westminster, Hafod (now Bonc-yr-Hafod park), Bersham, Wynnstay, Wrexham and Acton, Llay Hall and Gatewen commencing operations.[117] By the 20th century, two deep coal pits were dug, one at Gresford opening in 1911,[10] and another at Llay Main.[117] In 1934, a colliery disaster in Gresford killed 261 miners, with 3 rescuers also killed in the rescue operations. In the late 20th century, the traditional industries of Wrexham, in particular coal-mining, went into decline. Llay Main closed in 1966, Hafod closed in 1968, Gresford Colliery closed in 1973, and Bersham Colliery closed in 1986.[10][117]

Industrial estate

editThere are 25 different industrial and business parks in the county borough,[28] with Wrexham Industrial Estate being the largest, located 2.5 miles east from Wrexham and on the site of a former World War II munitions factory.[49][118][119][120]

Wrexham Industrial Estate is the largest industrial area in Wales, among the top ten in the United Kingdom and one of the largest in Europe.[91][118][119][121] There are around 360 businesses in the estate, providing 10,000 jobs.[28] The main industries operating in the industrial estate include: banking and finance, automotive, engineering, pharmaceutical, aerospace, and food and beverage.[28] The Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine was manufactured at the Wockhardt UK facility in the industrial estate.[122]

HM Prison Berwyn, a Category C adult-male prison is located in the industrial estate, and opened in 2017.[123] It is the largest prison in the United Kingdom.[124] In Chirk, there is a Kronospan wood product production factory[125] and a Mondelez International (for Cadbury) factory.[126] Whereas at Llay, there is Magellan Aerospace[127] and a regional divisional HQ for North Wales Police.[128]

Retail

editWrexham serves as the main retail centre for the county borough. Its city centre, hosts Eagles Meadow shopping centre,[129][130] two markets (General and Butcher's),[131] Tŷ Pawb (former People's Market),[132] Island Green retail park, and a High Street.[99] A Monday market is held in the city on Queen's Square.[131]

Notable retail areas outside the city centre are: Plas Coch retail park and Gwersyllt retail park. The county borough is also connected to shopping destinations in Chester, Broughton and Liverpool.

Sport

editWrexham is regarded as the "spiritual home of Welsh football",[133][134] with a Football Museum for Wales proposed to be set up in the city.[134][135][136][137] The county borough is home to the oldest club in Wales and third oldest association football club in the World, Wrexham A.F.C., which plays in the oldest stadium in Wales. The Football Association of Wales was founded on 2 February 1876 at the Wynnstay Arms Hotel in Wrexham.[138] The first association football match in Wales is said to have been in or near Wrexham.[139][140]

Notable stadia in the county borough include the Racecourse Ground, the oldest in Wales; The Rock; and an athletics stadium at Queensway.

Football

editThe county borough is home to Wrexham A.F.C., formed in 1864; they are the oldest club in Wales and the third[141] oldest professional association football team in the world. The team competes in the EFL League Two, the fourth tier of the English football league system.[99][142] Wrexham A.F.C's home stadium, the Racecourse Ground, is the world's oldest international stadium that still continues to host international games, and its neighbouring Turf Hotel pub is the oldest pub to any sporting stadium in the world.[141] The team train at Colliers Park, Gresford,[143] and have an equivalent Women's team. The team's rivalry with Chester City F.C. (now Chester F.C.) is described as the "Cross-border derby". In 1869, another football team composed of footballers from Ruabon, was formed in Plas Madoc, later becoming the Cefn Druids following a merger.[139][140][144]

As of March 2022[update], aside from Wrexham A.F.C., all other teams in the county borough play in the Welsh football league system:

- In the Cymru Premier, the highest tier (Tier 1), only Cefn Druids A.F.C. play, based at The Rock, Rhosymedre.[145][146]

- In the tier 2 Cymru North league, Gresford Athletic F.C. play.[147]

- In the tier 3 Ardal Leagues: Brickfield Rangers F.C., Brymbo F.C., Cefn Albion F.C., Chirk AAA F.C., Llay Welfare F.C., Penycae F.C., Rhos Aelwyd F.C. and Rhostyllen F.C.[148]

- In the tier 4 North East Wales Football League: Cefn Mawr Rangers F.C., Chirk Town F.C., Coedpoeth United F.C., FC Queens Park, Lex Glyndwr XI F.C. and Overton Recreation F.C. play[149] This tier 4 league also have a tier 5 championship, containing the Wrexham County Borough teams of Bellevue, Borras Park Albion, Brymbo Lodge, FC United of Wrexham, Johnstown Youth, and Ruabon Rovers. A Wrexham Town Police Station F.C. was also set up in 2022.[150]

Rugby

editWrexham RFC is a Welsh rugby union team based in Wrexham; it is a member of the Welsh Rugby Union and was a founding club of the North Wales Rugby Union, itself founded in Wrexham in 1931.[151] The club is located to the east of Rhosnesni, Wrexham.

Between 2010 and 2021, the North Wales Crusaders were based in Wrexham; firstly at the Racecourse Ground, then at the Queensway Stadium in Caia Park, Wrexham.[152]

Horse racing

editBangor-on-Dee racecourse is located in Bangor-on-Dee, and has held horse racing events since February 1859. It is the only racecourse in North and Mid Wales.[153][154] Prior to being a football stadium and home to Wrexham A.F.C., the Racecourse Ground once held horse racing events as part of the Wrexham Gold Cup and the Silver Cavalry Cup, with the first held on 29 September 1807.[155] Horse racing ended at the Racecourse Ground in 1857.[49][155]

Transport

editWrexham County Borough's transport system is part of Transport for Wales' North Wales Metro bus and rail improvement programme.[156]

Air

editThere are no airports in the county borough; the nearest are at: Birmingham, Liverpool John Lennon and Manchester. Railway connections are available to Birmingham International, Manchester Airport and Liverpool South Parkway stations.

In 1950, Wrexham (specifically Plas Coch) was a stop in the world's first scheduled helicopter passenger service between Liverpool and Cardiff by British European Airways.[157][158] The service ceased in March 1951 due to low demand.[157][158]

Railways

editThe county borough contains two railway lines:[159]

- The Borderlands line between Wrexham Central and Bidston (Birkenhead).[160][161] Gwersyllt and Wrexham General are also stops on this line.[162]

- The Shrewsbury–Chester line, with stops at Ruabon, Wrexham General and Chirk.[163]

The two railway lines interchange at Wrexham General, the main and busiest station in the county borough.[164]

There are two proposed railway stations in the county borough: Wrexham North and Wrexham South;[165][166][167] with plans to reopen parts of the Glyn Valley Tramway as a heritage railway.[28][168]

Two former major railway branches were:

- Wrexham and Minera Branch, which supported the steelworks at nearby Brymbo Steel Mill and Minera Limeworks. The last of the lines closed in 1982.

- Wrexham and Ellesmere Railway opened in 1895,[157] which passed through Wrexham city centre, St. Giles' Church and Maelor Saesneg towards Ellesmere; it closed in 1962 for passengers and 1981 for freight.[169]

Roads

editThe main roads in the county borough are

- A483, a dual carriageway, entering the county borough from Chester in the north and passing the outskirts of Wrexham,[162] Rhostyllen, Ruabon and meeting the A5 at Halton, near Chirk.[28]

- A5 (London-Holyhead Trunk Road) connects Oswestry (continuing southwards to London) and Llangollen (towards Holyhead) via Chirk and Froncysyllte.

- A534 connects Wrexham to Nantwich via Holt, with the A5156 near Borras,[28] linking the A534 to the A483 near Pandy.

- A541 connects Wrexham to Trefnant, Mold, Nannerch and the outskirts of Denbigh.[28]

Trunk roads are managed by the North and Mid Wales Trunk Road Agent on behalf of the Welsh Government.[170] There are no motorways in the county borough.

Buses

editWrexham bus station serves as the main terminus of the county borough. Services are operated by various bus operators such as Arriva Buses Wales, Arriva Midlands, TrawsCymru, Stagecoach North West, Llew Jones Coaches, Lloyds Coaches, M&H Coaches, Pat's Coaches, Tanat Valley Coaches and Valentine Travel.[171]

Popular bus services in the county borough include:

- Arriva Sapphire route 1 between Wrexham bus station and Chester

- TrawsCymru T3 Wrexham to Barmouth service.

Former tramways

editThere was an electric tramway between 1903 and 1927, connecting Wrexham to Rhosllanerchrugog, operated by Wrexham and District Electric Tramways.[157] The route was 4.4 miles (7.1 km) long, connecting the mining villages with Wrexham city centre and General railway station.[157] It was later replaced with motor buses in 1937.[49][157][172]

Demography

editAt the 2021 census,[iii] the county borough recorded a population of 135,100, and is the tenth most populous principal area in Wales, the same rank as 2011.[173][174] This population is a small increase of 0.2% from the 2011 census and lower than the national average of a 1.4% increase in population in 2021. The county borough is ranked thirteenth in population growth among principal areas, with both Denbighshire (2.2%) and Flintshire (1.6%) growing faster, although Powys also increased by 0.2%, and Conwy (also in ceremonial Clwyd) shrunk by 0.4%.[174]

The city of Wrexham had a population of 44,785, in the 2021 census,[29] accounting for 33% of the population of the county borough. This roughly covers the four communities of Acton, Caia Park, Offa and Rhosddu.[175] In the 2011 census, the Wrexham built-up area (BUA) was considered to also include western urban villages such as Gwersyllt, Brymbo and New Broughton, as well as Bradley and Rhostyllen, with a total population of 65,692 (2011 census), 48% of the county borough in 2011.[176] In the 2021 census, these new separate built-up areas are Bradley (1,315), Brynteg (9,225), Gwersyllt (7,110) and Rhostyllen (2,760).[29] There is also the BUAs of Coedpoeth (4,740), Gresford (4,945) and Llay (4,665) in the north to north-west of the county borough.[29] The other largest settlement is Rhosllanerchrugog with a community population of 9,694 in 2011[177] while its 2021 built-up area was 12,785 residents.[29] Other southern 2021 built-up areas include Acrefair and Cefn Mawr (6,905), Ruabon (3,410), and Trevor (1,395).[29] Holt's BUA had 1,085 residents in 2021, while the community of Chirk had a population of 4,468 in 2011,[178] and its 2021 built-up area population was 3,935.[29]

The county borough has 1,300 more females than males, with 68,200 females (50%) to 66,900 males (50%).[173] The county borough is twelfth in population density of the principal areas of Wales, with 268 people per square kilometre, more than the national average of 150. The most populous five-year age group are those aged 50–54 with 10,100 people (7%).[173] With a 19.5% growth in those aged 65 years and over, a decrease of 3.9% aged 15–64, and a decrease of 3.6% of children under 15 years old. In a 2020 population projection, Wrexham County Borough's population is expected to shrink slightly by 2028.[179]

The average age in the county borough is 42 years, with more than 25% of the population being in the 45 to 64 age cohort in 2011.[91]

At the 2011 census, 96.9% of the population was recorded to be White, made of 93.1% English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/ British, 0.4% Irish and 3.4% other White. The next largest eithnic group in 2011 was Asian/Asian British at 1.7%, with 0.6% identifying as Indian. 0.5% of the 2011 population were Black, and 0.2% other ethnic.[92]

93.7% of the population was born in the United Kingdom, 69.2% from Wales, 23.4% from England, 0.8% from Scotland, and 0.3% from Northern Ireland. 0.3% from the Republic of Ireland, 3.4 from the European Union (excluding Ireland), and 2.6% from other countries. 71.2% held a British passport, 24.3% no passport, 3.3% an EU member passport, and 1.2% other.[92]

95.8% of the population over 16 had English at their main household language. 65.1% of the population classed themselves as part of a religion, of which: 63.5% were Christian, 0.6% Muslim, 0.4% Hindu and 0.6% other. 27.4% had no religion, and 7.5% religion not stated.[92]

66% of waste is either recycled, reused or composted in the county borough between 2018 and 2019, 3% higher than the Welsh average.[180]

In 2011, 94.7% of the population identified with a UK nation identity consisting of either a Welsh/English/Scottish/Northern Irish or British identity, with 60.3% having part or full Welsh identity. 0.4% had a mixed identity between Welsh/English/Scottish/Northern Irish/British and another identity. 3.4% of the population had other non-UK identities.[28]

Some of the top 10% deprived areas in Wales are located in the county borough, these five Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) are; Queensway 1, Wynnstay, Plas Madoc, Queensway 2 and Cartrefle 2.[28]

Welsh-language

editOnly 12.2% of Wrexham County Borough's population at the 2021 census could speak Welsh, lower than the national average of 17.8%, making the county borough largely anglophone.[181] At the previous census in 2011, the percentage in Wrexham County Borough was 12.9%.[182] The highest proportion of Welsh-language speakers in the county borough is in the rural Ceiriog Valley ward, where 31.2% can speak the Welsh language. The ward of Wynnstay in Wrexham has the lowest proportion of Welsh-language speakers with 7.7%. Therefore, Welsh is more likely to be spoken in more rural areas of the county borough.[28]

Wrexham council have a "poor performance" in providing services in the Welsh language, due to the prevalence of translation errors. There were 34 public complaints put to the council between April 2018 to March 2019,[183] to the Welsh Language Commissioner.[184]

Health

editHealth in the county borough has been managed since 2009 by the NHS Wales local health board, Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board which covers all of North Wales.[185][186] Prior to Betsi Cadwaladr LHB, there was a separate Wrexham LHB and the North East Wales NHS Trust[187] based at Wrexham Maelor Hospital.

As of March 2017[update], the life expectancy in the county borough is 65 years for both Males and Females.[28]

Wrexham has increasing levels of child poverty.[188]

Hospitals

editThe main general hospital in the county borough is Wrexham Maelor Hospital in Wrexham, opened in 1985, and has an Accident and Emergency department.[10] A private hospital known as Spire Yale, operated by Spire Healthcare is located next to Wrexham Maelor Hospital. There is a smaller community hospital in Chirk, and a former Polish community hospital in Penley, the latter opened in 1946 for treating Polish people following the Second World War, and was closed in 2002.[189] There is also an adult male-only independent mental health hospital known as the New Hall Hospital near Ruabon.[190] The Wrexham & East Denbighshire War Memorial Hospital, located in Wrexham city centre, was built in the aftermath of World War I and fundraised by the local population from 1918 to 1927, to commemorate those killed in the war.[191] The hospital closed in 1986, and now serves as part of Yale College (now part of Coleg Cambria).[49]

Education

editHigher and further education

editThe county borough houses one university, which is located in the city of Wrexham, Wrexham University, and was awarded university status in 2008 as Glyndŵr University.[192] Bangor University has a healthcare school near Wrexham Maelor Hospital.[193] The main further education provider in the county borough is Coleg Cambria,[194] formed in 2013 from the merger of Yale College, Wrexham and Deeside College in Flintshire. Coleg Cambria also provides some higher education, and has two main sites in Wrexham, at Yale Grove Road in the city centre, and Bersham Road to the south-west of the city centre in Offa.[194]

Schools

editThere are a total of 68 schools in the county borough.[91] Of those, nine are secondary schools, including one Welsh-medium secondary school of Ysgol Morgan Llwyd, and the only shared-faith secondary school in Wales of St Joseph's Catholic and Anglican High School. Three secondary schools have Sixth forms; those being The Maelor School, Ysgol Morgan Llwyd, and Ysgol Rhiwabon.[195] The other five secondary schools are Ysgol Bryn Alyn, Ysgol y Grango, Darland High School, Rhosnesni High School, and Ysgol Clywedog.[195] There is a Special School of St Christophers in Wrexham.[196] For the 2015/2016 school year eight of the fifty-nine primary schools at the time were Welsh-medium or bilingual.[28]

In 2019, secondary schools in Wrexham were criticised by Estyn, the Welsh education and training inspectorate, for having the poorest attendance of the principal areas in Wales.[197] In February 2022, just under 30% of primary school buildings in Wrexham County Borough are in "poor" condition.[198] Although by 2023, the council stated that no reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete have been identified in local school buildings.[199]

Twinning

editMärkischer Kreis, Germany

Racibórz, Poland

Wrexham County Borough is twinned with the German district of Märkischer Kreis[98] and the Polish town of Racibórz.[49][200]

The first twinning was established on 17 March 1970 between the former Kreis Iserlohn and Wrexham Rural District.[201] Its early success ensured that, after local government reorganisation in both countries in the mid-seventies, the twinning was taken over by the new councils of Märkischer Kreis and Wrexham Maelor Borough Council and, in 1996, by Wrexham County Borough Council.

In 2001 Märkischer Kreis entered a twinning arrangement with Racibórz, a county in Poland, which was formerly part of Silesia, Germany. In September 2002, a delegation from Racibórz visited Wrexham and began discussions about cooperation which led to the signing of the Articles of Twinning between Wrexham and Racibórz in March 2004. The Wrexham area has strong historical links with Poland. Following World War II, many service personnel from the Free Polish armed forces who had been injured received treatment at Penley Polish Hospital. Many of their descendants remain in the area.

Culture and tourism

editIn 2015, it is estimated the county borough attracted 1.86 million visitors, and brought in more than £100 million for the tourism industry.[28][99]

Three of the Seven Wonders of Wales are located in the county borough, those wonders being: "Wrexham steeple", "Gresford bells", and " Overton yew trees".[99] Elihu Yale, after which Yale University is named after, is buried in Wrexham, with his tomb located at St Giles' Parish Church.[202] Local archives relating to the city and county borough are held at the Wrexham Archives, in the Wrexham County Borough Museum, Wrexham.

Since 1876, the county borough has hosted the National Eisteddfod of Wales eight times, six hosted in or near Wrexham in 1876,[203] 1888, 1912, 1933, 1977 and 2011; with Rhosllanerchrugog hosting in 1945 and 1961.[204] Also held in 1876, was the Wrexham Art & Industry Exhibition.[49][120] The first Wrexham Science Festival was held in 1998.[10]

Focus Wales, an international new music festival is hosted in the city of Wrexham.[205] Tŷ Pawb, an art and cultural centre in the city plays host to many cultural events and exhibitions.[99][206] Wales Comic Con was founded in 2007 and its first event held in Wrexham in 2008, prior to the moving of its events to Telford in 2019 (as Wales Comic Con: Telford Takeover) due to the small venue at Wrexham's university.[207]

There are two public market halls in Wrexham city centre, the Butcher's Market and General Market.[131] A third, People's Market, was converted to the Tŷ Pawb cultural centre in 2018. A weekly Monday market is held in Queen's Square in Wrexham.[131]

Tourism accounts for £116 million and 1,600 jobs for the county borough, increasing 38% between 2012 and 2017.[208]

In 2020, a science discovery centre known as "Xplore!" opened in Wrexham city centre, succeeding the Techniquest centre at Glyndŵr University.[209]

There are adventure playgrounds at The Venture in Caia Park and The Land in Plas Madoc.

The oldest surviving engine house in Wales is present at Penrhos near Brymbo.[210]

In October 2021, the council's bid for UK City of Culture in 2025 made it onto the competition's shortlist of only 8 shortlisted places in the UK, outbidding 12 other places (20 applied in total) and being the only one of the five bids from Wales making it onto the shortlist. In March 2022, Wrexham County Borough's bid for City of Culture made onto the competition's shortlist of only four places, the only non-English bid.[211][212] On 31 May 2022, Wrexham lost to Bradford's bid.[213]

Public art and symbols

editNotable buildings and structures such as St Giles' Church, Chirk Castle and Pontcysyllte Aqueduct also act as symbols for the county borough.

The "Acton Dog" has become a symbol of Wrexham city, inspired by the four greyhound fibre glass statues on top of Acton Gate at the entrance of the former Acton Estate, they were the symbol of the Cunliffe family.[49][214] Some settlements in the county borough host a colliery wheel as a welcome sign, highlighting the areas coal-mining industry heritage.[215]

"Babs" was a modified Higham Special sport racing car designed in the county borough.[216] Designed, built and driven by John Godfrey "J.G." Parry-Thomas from Wrexham, it set the land speed record of 171 miles per hour (275 km/h) in Pendine Sands, Carmarthenshire in April 1926.[217] Parry-Thomas was killed in the car on the beach,[218] aged 42, during his attempt on 3 March 1927 to regain his speed record from Malcolm Campbell.[217] The car was buried beneath the sand dunes on the beach until 1969, when it was later recovered, restored and remained on display at the Pendine Museum of Speed until 2018, when it was temporarily relocated to Beaulieu Motor Museum,[218] until the completion of the Pendine Sands of Speed Museum.

Waking the Dragon was a proposed bronze sculpture to be built near Chirk, it was first proposed in 2010,[219] and granted permission in 2011,[220] with progress stalling by 2016 due to a lack of funding.[221]

Castles

editChirk Castle is located to the south of the county borough,[222] and there are notable remains of a medieval castle in Holt in the county borough's north-east.[223][224] There was historically a motte and bailey castle at The Rofft site in Marford, and another former motte and bailey castle known as "Wristlesham" in Erddig.

Chirk Castle, a National Trust property, is located on the outskirts of Chirk.[222] It is also within the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB, which extends to the Chirk Castle Estate.[19]

Holt Castle is located in the village of Holt, along the banks of the River Dee next to the English border.[223][224] It was built between 1283 and 1311 by Earls of Surrey, John de Warenne and his grandson, following Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the Prince of Wales' defeat.[223][224]

Churches

editThe three of the Seven Wonders of Wales present in the county borough are all or part of churches. St Giles' Parish Church is a 16th-century gothic church located in the historic centre of Wrexham.[225] All Saints' Church, sometimes described as the "perfect Cheshire church in Wales", is a late-15th century church in Gresford,[226] and in Overton-on-Dee, there is St Mary the Virgin Church, with its ring of Yew Trees being one of the seven wonders of Wales.[227]

Wrexham is also home to Wrexham Cathedral (Cathedral Church of Our Lady of Sorrows or St Mary's Cathedral), a Catholic Cathedral which is the seat of the Bishop of Wrexham, and mother church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wrexham since 1987.[228][229] The cathedral also hosts a chapel dedicated to Richard Gwyn, a martyr who died in Wrexham.[230] Remaining Catholic churches are part of the Wrexham Deanery. Other major churches include St Mary's Church in Ruabon, and St Chad's Church in Holt, the latter having English Civil War bullet holes present in the building.[230]

Country estates and halls

editThe most notable country estate is at Erddig Hall, a Grade-I listed National Trust property, located to the south of Wrexham. Situated on an escarpment above the River Clywedog, the 18th century country house is surrounded by a 1,900-acre (7.7 km2) estate, including parkland and woodlands.[231]

Another historic estate is the Wynnstay estate near Ruabon. Notably the home of the Williams-Wynn family, the Wynnstay Hall stands above the River Dee overlooking the Vale of Llangollen and Y Berwyn.[232] The family vacated the building in 1948, with it first turned into a school, and now houses and apartments.[49][233] Trevalyn Hall, a Grade II listed manor house in Rossett, has also been converted to separate homes in the 1984.[234]

Marchwiel Hall, a 19th-century private Grade II listed hall is situated near Marchwiel. The estate is home to a cricket ground and pavilion, which serves as the home for the Marchwiel and Wrexham Cricket Club, on the only open part of the estate to the public. The hall has been on sale for £2.5 million.[235]

Brynkinalt Hall is a Grade-II* listed private property, built in 1612, near Chirk.

Iscoyd Park located near the border with Shropshire to the east in English Maelor, serves as a wedding venue.[236]

Pen-y-Lan Hall, another Grade II listed building, located near Ruabon, has become known for Ghost sightings, with Ghost hunting events held at the hall.[237]

Other halls include: Nant-y-Ffrith Hall, Tudor Court, The Gelli, Wynn Hall and the former Brymbo Hall, a lost British country house.

Scheduled monuments

editNotable people

editTourist attractions

editIndustrial heritage

editBersham

editBersham Colliery was opened in 1864, as the Glan-yr-afon Colliery, located near Rhostyllen. It was operated by the Bersham Coal Company, and it was not until 10 years later in 1874 that coal was produced at the site. The colliery was closed and partially demolished in December 1986. Its No.2 shaft headgear with its colliery wheel and an engine house with an electric winding gear, as well as other buildings remain standing as part of a small industrial estate. The buildings for the No.2 shaft have been proposed to form a small mining museum for the former colliery.[238]

Bersham Ironworks were opened in 1715 by Charles Lloyd, and are situated in the Clywedog Valley.[239][240] By the 1750s it was producing iron cannons. Isaac Wilkinson took over in 1753, and produced cannons for the Seven Years' War.[239] In 1763 it was passed to John "Iron Mad" Wilkinson, who developed a new method of gun manufacture with Francis Bacon, where the cannons were first cast solid then bored out afterwards.[239] Bersham reached its peak in 1795 and closed in 1812.[241][242] A Smelting works was opened in Brymbo in 1793.[230][8]

Bersham Heritage Centre, in the Bersham Ironworks, operated from 1983 until 2014, and was the home for the Wrexham County Borough Museum's Industrial History collection, and performed as the centre of Wrexham's Industrial Heritage.[10][240][243]

Brymbo

editSteel was a former industry for the county borough, with the Brymbo Steelworks reaching its peak in steel production in the 1960s and early 1970s. Over 2,000 workers were employed at the steelworks until its closure in 1990. There is a sculpted archway, "the arc", in Lord Street, Wrexham to commemorate the industry.[230] In 2020, the site of the former steelworks were proposed to be re-developed into a visitor attraction and community hub with funding from the National Lottery.[244]

Minera

editLead Mines in Minera, opened in 1845, mining lead until its closure in 1914. The site has since been converted into a country park, covering 53 acres (0.21 km2) of grassland, woodland and the former lead mines, it also hosts a tourist centre.[39][245]

Notable sites and bridges

editThere are various aqueducts and viaducts in the south of the county borough, crossing the River Ceiriog and River Dee. These include: Chirk Aqueduct,[246][247] Chirk Viaduct,[248] Pontcysyllte Aqueduct,[249] and Cefn Mawr Viaduct.[250] There is also a canal tunnel at Chirk.[247][251]

The main canal is the Llangollen Canal from Llangollen which travels to Chirk before entering England.[252] Sections of the historically proposed and never completed Ellesmere Canal were proposed to pass right through the centre of the county borough, from Chester in the north to meet the River Ceiriog at Chirk until reaching Ellesmere.[253]

Notable bridges include: Pont Cysyllte,[254] Bangor-on-Dee Bridge[255] and Holt Bridge.[256]

World Heritage Site

editThere is a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the county borough, the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal, containing the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, constructed in 1805 and the tallest navigable canal boat crossing in the world, and 11 miles (18 km) of the Llangollen Canal.[230] It was designated in June 2009, following the 33rd meeting of the World Heritage Committee in Seville.[257] The Trevor Basin is located northwards of the aqueduct, and in 2021 was awarded funding from the UK Government's Levelling up fund.[258] The Brymbo Fossil Forest near Brymbo is a palaeobotanitcal site[259] and SSSI[260] of Early Carboniferous fossils[259] said to be, by locals, a potential world heritage site.[261]

Media

editCalon FM is the community radio station for the city of Wrexham.[262] Global Media & Entertainment, which owns Capital FM and operates Heart FM (on behalf of Communicorp UK), broadcasts Capital North West and North Wales,[263] Heart North and Mid Wales[264] and some broadcasts of Capital Cymru[265] from their studios in Gwersyllt, Wrexham, the former studios of the Marcher Radio Group.

BBC Cymru Wales has a local radio station in Wrexham for some local broadcasts.[266][267]

The Leader is the local newspaper in Wrexham.[268] There is also a local media website known as Wrexham.com.[269]

Music

editTheatr Stiwt (Stiwt Theatre) in Rhosllanerchrugog, with 450 seats, opened in 1926, and hosts various drama and musical performances.[270][271] The Grove Park Theatre, described as Wrexham's "oldest amateur theatre", is located on Hill Street in Wrexham since 1954.[272] The 890-seat William Aston Hall in Wrexham University, and the 150-seat Studio Theatre in Coleg Cambria Yale also acts as a venue for events.[270] The Wrexham Musical Theatre Society is based at the 120-seat Riverside Studio Theatre.[270]

The county borough is home to numerous choirs such as Brymbo, Y Rhos, Rhos Orpheus, Dyffryn Ceiriog and Fron Male Voice Choir.[270] The latter is regarded as the oldest boy-band in the world.[270]

Museums

editWrexham County Borough Museum is the main museum in the county borough. Located in Wrexham city centre on Regent Street,[273] it is housed in County Buildings which was built in 1857 as a military barracks,[49][274] later becoming a police station and Magistrates' court in 1879,[49][274][275] until it opened as a museum in 1996 and refurbished in 2010–11.[274] The museum also hosts the Wrexham Archives, and the building is proposed to also host a national football museum, projected to open by 2024.[276] Wrexham was chosen due being the location where the FAW was founded in 1876 and having the oldest club and oldest football ground in Wales.[135][136][137]

See also

edit- List of places in Wrexham County Borough for a list of towns and villages

- North Wales

- Wrexham Maelor

- Wrexham Rural District

Notes

edit- ^ excluding two independents who did not join.

- ^ Only for Llangollen Rural

- ^ As of 28 June 2022[update], only the initial results of the census have been released, only covering local authorities and Wales as a whole. Settlement figures have yet to be released.

References

edit- ^ "Council and democracy". Wrexham County Borough Council. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Crown Office | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

THE QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 1 September 2022 to ordain that the County Borough of Wrexham shall have the status of a City.

- ^ a b "Wrexham – The Big Town Story". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Changing Times, Changing Places". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "The Charter of Incorporation for the Borough of Wrexham". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham Borough Council, records of – Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b Live, Cheshire (26 February 2009). "Early history of Wrexham". CheshireLive. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham Borough Council, records of". North East Wales Archives.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "A History of Wrexham". Local Histories. 14 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Local Government Act 1972". legislation.gov.uk. UK Parliament. 1 February 1991. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Report and Proposals of the Local Government Commission for Wales, 1963.

- ^ "Wrexham Maelor Borough Council, records of – Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Local Government (Wales) Act 1994". legislation.gov.uk. UK Parliament. 5 July 1994.

- ^ "The Denbighshire and Wrexham (Areas) Order 1996". legislation.gov.uk. UK Parliament. 9 December 1996.

- ^ "Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust – Projects – Historic Landscapes – Vale of Llangollen and Eglwyseg –". www.cpat.org.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ "Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust – Projects – Historic Landscapes – Vale of Llangollen and Eglwyseg –". www.cpat.org.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^

- "Last word over boundary row". 30 January 2002. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- Cabinet Meetings 18/07/00 (PDF). Denbighshire County Council. 18 July 2000.

- "Festival town's place on map decided". 12 April 2002. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- Review of part of the boundary between the County of Denbighshire and the County Borough of Wrexham in the area of the communities of Llangollen and Llantysilo in the County of Denbighshire and the communities of Penycae, Cefn, Llangollen Rural, Chirk, Glyntraian and Llansantffraid Glyn Ceiriog in the County Borough of Wrexham — Report and Proposals (PDF). Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales. 2002.

- ^ a b "The AONB". Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "A Market Town". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust – Projects – Historic Landscapes – Maelor Saesneg – Administrative Landscapes". www.cpat.org.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Biodiversity in Wrexham – Wrexham County Borough Council". yumpu.com. Wrexham County Borough Council. September 2009. pp. 9, 12, 16. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Offa's Dyke Path". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Wat's Dyke Way". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "The Dee Way Walk". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "The Guide to the Maelor Way". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Trust, Woodland. "Fenn's, Whixall & Bettisfield Mosses". Woodland Trust. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Wrexham's Well-being Assessment March 2017" (PDF). wrexhampsb.org. Wrexham Public Services Board. March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Within the dataset under 1d and the given name of the BUA."Towns and cities, characteristics of built-up areas, England and Wales: Census 2021". 2 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ "Wrexham Built-up area Local Area Report". www.nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Rhosllanerchrugog Built-up area". Nomis. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^

- "The Oak at the Gate of the Dead | Peoples Collection Wale". www.peoplescollection.wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- "Oak tree in Chirk nominated as Europe's finest". BBC News. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Wrexham Parks Strategy 2009 (PDF). Wrexham County Borough Council. 5 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Natural Resources Wales 2014 data only showed seven areas under the Country Park designation within the boundaries of Wrexham County Borough. "Country Parks | DataMapWales". datamap.gov.wales. Natural Resources Wales. 21 July 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "Parks & Countryside". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^

- "Alyn Waters Country Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- "Alyn Waters Country Park | VisitWales". www.visitwales.com. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Bonc Yr Hafod Country Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Erddig Country Park, Clwyd". Countryfile. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Minera Lead Mines and Country Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Moss Valley Country Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Tŷ Mawr Country Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Ty Mawr Country Park". North East Wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Brynkinalt Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Erddig Country Park, Clwyd". Countryfile. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Stevens, Gill (6 April 2022). "New path now links Erddig Country Park, Marchwiel and the Clywedog Trail – news.wrexham.gov.uk". Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Nant Mill Visitor Centre | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Stryt Las Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Bellevue Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "The Big Town Story Interactive Map". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Acton Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Ponciau Banks Park | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Discover the Clywedog Trail in Wrexham". North East Wales. 26 February 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ Live, North Wales (16 November 2009). "Offa's Dyke trail through Wrexham improved". North Wales Live. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Bonc yr Hafod History, nature and walks" (PDF). wrexham.gov.uk. Parks, Countryside and Public Rights of Way Service, Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^

- SSSI sources:

- Jones, Tim, ed. (25 January 2008). CORE MANAGEMENT PLAN INCLUDING CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES FOR Johnstown Newt Sites Special Area of Conservation (SAC) (PDF). Countryside Council for Wales.

- SITES OF SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC INTEREST CITATION WREXHAM STRYT LAS A'R HAFOD (PDF). Countryside Council for Wales.

- ^ "About the Chief Executive | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Wales council elections 2022: A simple guide". BBC News. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham Council Elections 2022". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Bagnall, Steve (5 May 2017). "Local election results: Independents hold onto Wrexham Council". North Wales Live. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Bagnall, Steve (17 May 2017). "Independents and Tories set to run Wrexham council". North Wales Daily Post. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ Randall, Liam (11 May 2022). "Wrexham council to be led by Independents and Conservatives". North Wales Live. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham Council elections 2022: Here's who's standing in your area". The Leader. 7 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Eurostat – Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "North East Wales". VisitWales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Things to do, events, Wales holidays ideas | North Wales". North East Wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Ambition North Wales". ambitionnorth.wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "About North Wales Police". www.northwales-pcc.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Who we are and our stations – About Us – North Wales Fire And Rescue Service". www.northwalesfire.gov.wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "About the Health Board – Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board". bcuhb.nhs.wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "2023 Parliamentary Review - Revised Proposals | Boundary Commission for Wales". Boundary Commission for Wales. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Councillors, MPs and MSs | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Different types of elections | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^

- Results for:

- Wrexham constituency "Election 2019: What does Wrexham really think?". UnHerd Britain. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Clwyd South constituency "Election 2019: What does Clwyd South really think?". UnHerd Britain. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Election results | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Randall, Liam. "Sarah Atherton: Wrexham elects Conservative MP for first time in history". Leader Live. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ "General Election 2019 – Wrexham turns blue for the first time". www.shropshirestar.com. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "The Tories are well ahead in Wrexham, part of Labour's "Red Wall"". The Economist. 5 December 2019. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "'People are fed up, tired and scared': the battle for Wrexham". the Guardian. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham parliamentary constituency – Election 2019 – BBC News". Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "In Wrexham, voters are abandoning Labour over Brexit". New Statesman. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Randall, Liam (7 May 2021). "Senedd Election 2021: Wrexham constituency result in full". North Wales Live. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Mosalski, Ruth; Burkitt, Sian (7 May 2021). "Senedd election 2021 result in Wrexham: Labour hold seat". WalesOnline. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham mulls launching fourth bid for city status". BBC News. 7 July 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham ignored again as St Asaph gets city status". The Leader. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Official – Wrexham is now a city". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Gareth (8 November 2021). "Wrexham doesn't 'deserve to be a city' according to new survey". Nation.Cymru. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Winson, Lottie (5 February 2024). "Members at Welsh council "frequently undermine" professional officers by requesting second opinions from external legal providers, watchdog finds in governance report". Local Government Lawyer. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Wrexham councillors hit back over criticism of 'fractured' relations with officers". The Leader. 9 February 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Wrexham Council 'aware' of 'malfeasance in public office by councillors' report". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "UK – Case study 1: Wrexham". Agents of Change in Old-industrial Regions in Europe. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Statistics and data | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Custom report – Nomis – Official Labour Market Statistics". www.nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "A History of Wrexham". Local Histories. 14 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Leather Making in Wrexham – Introduction". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brewers and Breweries". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Brewers & Boozers Tour – Why Wrexham?". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Watts, H. D. (April 1975). "Lager Brewing in Britain". Geography. 60 (2). Geographical Association: 140. JSTOR 40568382.

- ^ a b "5 things you may not have known about Wales's links with Germany". Welsh Government News. 6 February 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Things to do in Wrexham, the largest town in North East Wales". VisitWales. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Cheers! Wrexham Lager to unveil new beer this week". The Leader. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Changing face of iconic Wrexham Lager Brewery". The Leader. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Wrexham Lager & Bootlegger 1974 Pilsner – Premium Welsh Lager". www.wrexhamlager.co.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Brewers & Boozers Tour – Wrexham Lager Brewery". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Thirst Come Thirst Served – A history of Border Breweries – Wrexham History". Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Brewers & Boozers Tour – Soames' Brewery". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ morningadvertiser.co.uk (14 November 2011). "Britain's oldest lager re-launched in north Wales". morningadvertiser.co.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham Lager to hit Aldi stores across Wales and England". The Leader. 28 January 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to Big Hand Brewery North Wales". bighandbrewing.co.uk. Big Hand Brewing Company Limited. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^

- "About us". Magic Dragon Brewing Wales. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- "Couple brewing success with a splash of Welsh magic". The Leader. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- "Magic Dragon Brewery Tap Room Opens in Wrexham!". thisiswrexham. This is Wrexham Partnership. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- "Magic Dragon Brewing is officially "Great Taste" as they win top excellence awards". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "About The Bridge End Inn, Ruabon near Wrexham". bridgeendinnruabon. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Gregory, Rhys (25 June 2021). "Rise in number of Welsh Food and Drink businesses looking to export". Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "about | Sandstone Brewery | Wales". Sandstone Brewery. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Town's name built on red bricks". 29 February 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Brickworks". Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal World Heritage site. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "'Tales From Terracottapolis' – exhibit to tell the red brick tale of Wrexham". The Leader. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Henry Dyke Dennis and the Red Works – Wrexham History". Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d "The History Of Wrexham's Mining Heritage". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Wrexham Industrial Estate – One of the largest industrial areas in Europe". www.wrexhamindustrialestate.co.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Wrexham Industrial Estate". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b "A Hive of Industry". wrexham.gov.uk. Wrexham County Borough Council. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^

- Hughes, Owen (5 October 2021). "Building work picking up pace at largest industrial estate in Wales". Business Live. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- "Major plans to expand Wrexham Industrial Estate 'could boost area's economy'". The Leader. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Ministers praise Wrexham-based Wockhardt on COVID-19 vaccine success". GOV.WALES. 24 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham prison set to accept inmates on 27 February". BBC News. 18 January 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^

- "First inmates move to HMP Berwyn super-prison, Wrexham". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- "Super-prison: How does HMP Berwyn compare to others?". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Kronospan Chirk – new investment and developments | Kronospan Worldwide". www.kronospan-worldwide.com. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^

- "Additional Office Locations". Mondelēz International, Inc. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- "Chirk's chocolate factory now using 100 renewable electricity generated in Britain". The Leader. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^

- "Magellan Aerospace looks to expand factory in Wrexham by creating new facility". The Leader. 17 February 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Hughes, Owen (21 June 2021). "Airbus wing parts deal for Magellan in boost to North Wales sites". Business Live. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Morris, Lydia (8 November 2018). "Look around new £21m police station which has cells, solar panels and two gyms". North Wales Live. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Eagles Meadow Shopping Centre – Great restaurants, shopping and leisure all in one place". Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Porter, Gary (12 May 2015). "Wrexham's Eagles Meadow shopping centre is sold". North Wales Live. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Wrexham town centre markets | Wrexham County Borough Council". www.wrexham.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Market". Tŷ Pawb. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham 'spiritual home' for Wales football museum". BBC News. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Football Museum for Wales". Wrexham Heritage. June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Creation of new Football Museum for Wales in Wrexham takes step forward after new design team appointed". Wrexham.com. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Welsh Government "pressing ahead" with plans for National Football Museum in Wrexham". The Leader. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b Thomas, Gareth (25 June 2021). "A Football Museum for Wales – Design Team Announced – news.wrexham.gov.uk". Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ "FAW / Who are FAW?". www.faw.cymru. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b "The history of Welsh football". Wales. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b "The Story of Welsh Football". wrexham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Wrexham FC: Five things you need to know". BBC News. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Wrexham AFC: The new kids on the block gear up for first season in EFL League Two". ITV News. 3 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "Opening of world-class facilities at Colliers Park is boost for football in Wrexham and North Wales". The Leader. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Cefn Druids AFC | Our History". cefndruidsafc. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Cymru Premier Table – Football". BBC Sport. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Cefn Druids AFC | Our Home". cefndruidsafc. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Table :: Cymru Football". www.cymrufootball.wales. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Clubs". www.ardalnorthern.co.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Clubs – North East Wales Football League". clwydleagueeast.pitchero.com. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Lewis, Thomas (21 January 2022). "Police team take on an 'inclusivity 11' in bid to breakdown sporting barriers". North Wales Live. Retrieved 30 March 2022.