Sleepy Hollow is a 1999 gothic supernatural horror film[8] directed by Tim Burton. It is a film adaptation loosely based on Washington Irving's 1820 short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow", and stars Johnny Depp and Christina Ricci, with Miranda Richardson, Michael Gambon, Casper Van Dien, Christopher Lee, and Jeffrey Jones in supporting roles. The plot follows police constable Ichabod Crane (Depp) sent from New York City to investigate a series of murders in the village of Sleepy Hollow by a mysterious Headless Horseman.

| Sleepy Hollow | |

|---|---|

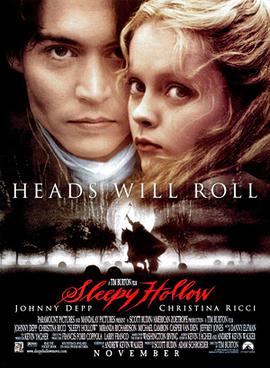

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tim Burton |

| Screenplay by | Andrew Kevin Walker |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" by Washington Irving |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki |

| Edited by | Chris Lebenzon |

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes[3] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $70–100 million[6][7] |

| Box office | $207.1 million[6] |

Development began in 1993 at Paramount Pictures, with Kevin Yagher originally set to direct Andrew Kevin Walker's script as a low-budget slasher film. Disagreements with Paramount resulted in Yagher being demoted to prosthetic makeup designer, and Burton was hired to direct in June 1998. Filming took place from November 1998 to May 1999. The film was an international co-production between Germany and the United States.

The film had its world premiere at Mann's Chinese Theatre on November 17, 1999, and was released in the United States on November 19, 1999, by Paramount Pictures. It received positive reviews from critics, with many praising the performances, direction, screenplay and musical score, as well as its dark humor, visual effects and atmosphere. It grossed approximately $207 million worldwide. Sleepy Hollow won the Academy Award for Best Art Direction.[9]

Plot

editIn 1799, New York City police constable Ichabod Crane is dispatched to the upstate Dutch hamlet of Sleepy Hollow, which has been plagued by a series of brutal murders: a wealthy landowner and his son, and a widow. Received by the insular town elders – wealthy businessman Baltus Van Tassel; town doctor Thomas Lancaster; the Reverend Steenwyck; notary James Hardenbrook; and magistrate Samuel Philipse—Ichabod learns that locals believe the killer is the undead apparition of a headless Hessian mercenary from the American Revolutionary War who rides a black steed in search of his missing head.

Ichabod begins his investigation, skeptical of the paranormal story. Boarding at the home of Baltus Van Tassel and his wife Mary Van Tassel, he is taken with Baltus's daughter Katrina by Baltus's dead wife Elizabeth. When servant Jonathan Masbath is killed, Ichabod takes Jonathan's son Young Masbath under his wing. They both exhume the victims on a tip from Philipse, learning that the widow died pregnant; Ichabod later witnesses the Horseman kill Philipse shortly after. He, Young Masbath and Katrina venture into the Western Woods, where a crone witch reveals the location of the Horseman's grave at the "Tree of the Dead." Ichabod digs up the Horseman's grave and discovers the skull has been taken, deducing that it has been stolen by someone who now controls him and that the tree is his portal into the living world.

That night, the Horseman slaughters the village midwife and her family, as well as Katrina's suitor Brom when he attempts to intervene. Ichabod deduces that the Horseman is only attacking his targets linked by a conspiracy. He and Masbath visit Hardenbrook, who reveals that the first victim, Peter Van Garrett, had secretly married the widow, writing a new will that left his estate to her and her unborn child instead of his grown-up son Dirk, the second victim. Ichabod deduces that all the victims (except Brom) are either beneficiaries or witnesses to this new will, and that the Horseman's master is the person who would have otherwise inherited the estate: Baltus, a Van Garrett relative.

Upon discovering the accusation, Katrina burns the evidence. Hardenbrook commits suicide and Steenwyck convenes a town meeting to discredit Ichabod, but Baltus bursts into the assembly at the church, announcing that the Horseman has killed his wife. The Horseman arrives at the church as the remaining elders turn on and attack each other. Steenwyck and Lancaster are killed, and the Horseman harpoons Baltus through a window, dragging him out of the church and acquiring his head.

Initially concluding that Katrina was controlling the Horseman, Ichabod later discovers that her diagram, which he believed summoned the Horseman, is actually one of protection and that Lady Van Tassel is actually alive and the real culprit. Katrina gets kidnapped by Lady Van Tassel, who explains her true heritage from an impoverished family evicted years ago by Van Garrett when he favored the Van Tassels instead and that she betrayed the Horseman to his death and stole his skull to control him. She swore revenge against Van Garrett and all who had wronged her, pledging herself to Satan if he would raise the Horseman to avenge her, and also to claim the Van Garrett and Van Tassel estates uncontested. Manipulating her way into the Van Tassel household by murdering Katrina's mother Elizabeth and seducing Baltus to marry her, she used fear, blackmail and lust to draw the other elders into her plot. Having eliminated all other heirs and witnesses, including her sister (who turns out to be the crone witch who aided Ichabod), Lady Van Tassel summons the Headless Horseman to kill Katrina to secure the fortune for herself.

Ichabod and Masbath rush to the windmill as the Horseman arrives. After an escape that destroys the windmill and the subsequent chase to the Tree of the Dead, Ichabod retrieves the Horseman's skull from Lady Van Tassel and returns it to him, breaking the curse, and setting the Horseman free from Lady Van Tassel's control. With his head restored, the Horseman spares Katrina and abducts Lady Van Tassel, giving her a bloody kiss and returning to Hell with her in tow. With the crimes solved, Ichabod returns to New York with Katrina and Young Masbath, just in time for the new century.

Cast

edit- Johnny Depp as Ichabod Crane: Crane is a quirky, yet sympathetic constable infatuated with integrating modern science into police procedures (early forensic science), but is very squeamish at the sight of blood and bugs.

- Christina Ricci as Katrina Anne Van Tassel: Ichabod's love interest and the only heir to one of the town's richest farmers. Ricci described her character as "a princess-y character, very one-sided, no emotional depth."[10]

- Miranda Richardson as Lady Mary Van Tassel (née Archer; she falsely uses "Preston" as her maiden name): The aloof wife of Baltus and stepmother of Katrina, who is revealed to be a vengeful witch. Richardson also portrays the Crone Witch, Lady Van Tassel's sister.

- Michael Gambon as Baltus Van Tassel: Katrina's father. After Peter Van Garrett is murdered, he is placed as the leader of the town.

- Casper Van Dien as Brom Van Brunt: A strong and arrogant aristocratic man who is romantically involved with Katrina.

- Jeffrey Jones as Reverend Steenwyck: The austere, corrupt town pastor.

- Christopher Lee as the Burgomaster.

- Richard Griffiths as Magistrate Samuel Philipse: The drunken town magistrate.

- Ian McDiarmid as Dr. Thomas Lancaster: The town doctor and surgeon.

- Michael Gough as Notary James Hardenbrook: The wizened, cowardly town notary.

- Marc Pickering as Young Masbath: An orphan who looks towards Ichabod as a father figure after his father is slain by the Horseman.

- Lisa Marie as Lady Crane (in flashbacks): Ichabod's mother who practiced benign witchcraft, for which she was killed by her strict religious husband.

- Steven Waddington as Mr. Killian

- Ray Park and Christopher Walken as the Headless Horseman: A brutal and sadistic Hessian mercenary sent to America during the American Revolutionary War who loses his head during battle. Walken portrays the Hessian while Park performs the Headless Horseman.

- Claire Skinner as Beth Killian: The town midwife.

- Alun Armstrong as the High Constable

- Mark Spalding as Jonathan Masbath

- Jessica Oyelowo as Sarah

- Tony Maudsley as Van Ripper

- Peter Guinness as Lord Crane (in flashbacks): Ichabod's fanatically sadistic father who tortured and killed his wife for practicing witchcraft.

- Sean Stephens as Thomas Killian

Other roles include Michael Feast as Spotty Man, Jamie Foreman as Thuggish Constable, Philip Martin Brown as a Constable, and an uncredited Martin Landau as Peter Van Garrett, Sleepy Hollow's chief citizen until his death at the hands of the Headless Horseman.

Production

editDevelopment

editIn 1993, Kevin Yagher, a make-up effects designer who had turned to directing with Tales from the Crypt, had the notion to adapt Washington Irving's short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" into a feature film. Through his agent, Yagher was introduced to Andrew Kevin Walker; they spent a few months working on a film treatment[11] that transformed Ichabod Crane from a schoolmaster from Connecticut to a banished New York City detective.[12] Yagher and Walker subsequently pitched Sleepy Hollow to various studios and production companies, eventually securing a deal with producer Scott Rudin,[11] who had been impressed with Walker's unproduced spec script for Seven.[13] Rudin optioned the project to Paramount Pictures in a deal that had Yagher set to direct, with Walker scripting; the pair would share story credit.[11] Following the completion of Hellraiser: Bloodline, Yagher had planned Sleepy Hollow as "a low-budget effects showcase with a spectacular murder every five minutes or so," characterized by its screenwriter as a "pretentious slasher movie".[14] Paramount had reservations about the film, interpreting it as a typical period piece—"I wouldn't say they weren't enthusiastic about it, but they didn't see the commercial viability," producer Adam Schroeder noted. "The studio thinks 'old literary classic' and they think The Crucible. There was a fear about that... We started developing it before horror movies came back."[15]

Paramount CEO Sherry Lansing revived studio interest in 1998.[13] Schroeder, who shepherded Tim Burton's Edward Scissorhands as a studio executive at 20th Century Fox in 1990, suggested that Burton direct the film.[16] Francis Ford Coppola's minimal production duties came from American Zoetrope; Burton only became aware of Coppola's involvement during the editing process when he was sent a copy of Sleepy Hollow's trailer and saw Coppola's name on it.[16] Burton, coming off the troubled production of Superman Lives, was hired to direct in June 1998.[17] Excited about Burton's involvement, Yagher stepped down as director "with good grace", remaining involved in the project as the lead creature effects artist.[15] Burton considered the film his first venture into a primarily horror-focused tone. "I had never really done something that was more of a horror film," he explained, "and it's funny, because those are the kind of movies that I like probably more than any other genre."[11] His interest in directing a horror film was influenced by his love for Hammer Film Productions and Black Sunday—particularly the supernatural feel they evoked as a result of being filmed primarily on sound stages.[15] As a result, Sleepy Hollow is an homage to various Hammer Film Productions, including Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde,[18] and other films such as Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, various Roger Corman horror films,[19] Jason and the Argonauts, and Scream Blacula Scream.[13] The image of the Headless Horseman had fascinated Burton during his apprenticeship as a Disney animator at CalArts in the early 1980s.[19] "One of my teachers had worked on the Disney version as one of the layout artists on the chase, and he brought in some layouts from it, so that was exciting. It was one of the things that maybe shaped what I like to do."[11] Burton worked with Walker on rewrites, but Rudin suggested that Tom Stoppard rewrite the script to add to the comical aspects of Ichabod's bumbling mannerisms, and emphasize the character's romance with Katrina. His work went uncredited through the WGA screenwriting credit system.[20][13]

Casting

editWhile Johnny Depp was Burton's first choice for the role of Ichabod Crane, Paramount required him to consider Brad Pitt, Liam Neeson and Daniel Day-Lewis.[15][21] Depp was cast in July 1998 for his third collaboration with Burton.[22] The actor wanted Ichabod to parallel Irving's description of the character in the short story. This included a long prosthetic snipe nose, huge ears, and elongated fingers. Paramount turned down his suggestions,[23] and after Depp read Tom Stoppard's rewrite of the script, he was inspired to take the character even further. "I always thought of Ichabod as a very delicate, fragile person who was maybe a little too in touch with his feminine side, like a frightened little girl," Depp explained.[13] He did not wish to portray the character as a typical action star would have, and instead took inspiration by Angela Lansbury's performance in Death on the Nile.[13] "It's good," Burton reasoned, "because I'm not the greatest action director, or the greatest director in any genre, and he's not the greatest action star, or the greatest star in any genre."[16] Depp modeled Ichabod's detective personality from Basil Rathbone in the 1939 Sherlock Holmes film series. He also studied Roddy McDowall's acting for additional influence.[23] Burton added that "the idea was to try to find an elegance in action of the kind that Christopher Lee or Peter Cushing or Vincent Price had."[16]

Sleepy Hollow also reunited Burton with Jeffrey Jones (from Beetlejuice and Ed Wood) as Reverend Steenwyck, Christopher Walken (Max Shreck in Batman Returns) as the Hessian Horseman, Martin Landau (Ed Wood) in a cameo role, and Hammer veteran Michael Gough (Alfred in Burton's Batman films), whom Burton tempted out of retirement.[16] The Hammer influence was further confirmed by the casting of Christopher Lee in a small role as the Burgomaster who sends Crane to Sleepy Hollow.[24]

Filming

editThe original intention had been to shoot Sleepy Hollow predominantly on location with a $30 million budget.[25] Towns were scouted throughout Upstate New York along the Hudson Valley,[11] and the filmmakers decided on Tarrytown[17] for an October 1998 start date.[22] The Historic Hudson Valley organization assisted in scouting locations, which included the Philipsburg Manor House and forests in the Rockefeller State Park Preserve.[12] "They had a wonderful quality to them," production designer Rick Heinrichs reflected on the locations, "but it wasn't quite lending itself to the sort of expressionism that we were going for, which wanted to express the feeling of foreboding."[26] Disappointed, the filmmakers scouted locations in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, and considered using Dutch colonial villages and period town recreations in the Northeastern United States. When no suitable existing location could be found, coupled with a lack of readily available studio space in the New York area needed to house the production's large number of sets, producer Scott Rudin suggested the United Kingdom.[11]

Rudin believed Britain offered the level of craftsmanship in period detail, painting and costuming that was suitable for the film's design.[27] Having directed Batman entirely in Britain, Burton agreed, and designers from Batman's art department were employed by Paramount for Sleepy Hollow.[16] As a result, principal photography was pushed back[28] to November 20, 1998, at Leavesden Film Studios, which had been recently vacated by Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[25] The majority of filming took place at Leavesden, with other work taking place at Shepperton Studios,[11] where the massive Tree of the Dead set was built using Stage H.[13] Production then moved to the Culden Faw Estate, Hambleden[29] for a month-long shoot in March, where the town of Sleepy Hollow was constructed.[11] "We came to England figuring we would find a perfect little town," producer Adam Schroeder recalled, "and then we had to build it anyway." Filming in Britain continued through April,[11] and a few last minute scenes were shot using a sound stage in Yonkers, New York the following May.[12][30]

Design

editResponsible for the film's production design was Rick Heinrichs, whom Burton intended to use on Superman Lives. While the production crew was always going to build a substantial number of sets, the decision was made early on that optimally fulfilling Burton's vision would necessitate shooting Sleepy Hollow in a totally controlled environment at Leavesden Film Studios.[32] The production design was influenced by Burton's love for Hammer Film Productions and the film Black Sunday (1960)—particularly the supernatural feel they evoked as a result of being filmed primarily on sound stages. Heinrichs was also influenced by American colonial architecture, German expressionist cinema, Dr. Seuss illustrations, and Hammer's Dracula Has Risen from the Grave.[15]

One sound stage at Leavesden was dedicated to the "Forest to Field" set, for the scene in which the Headless Horseman races out of the woods and into a field. This stage was then transformed into, variously, a graveyard, a corn field, a field of harvested wheat, a churchyard, and a snowy battlefield. In addition, a small backlot area was devoted to a New York City street and waterfront tank.[25]

Cinematography

editBurton was impressed by the cinematography in Great Expectations (1998) and hired Emmanuel Lubezki as Sleepy Hollow's director of photography. Initially, Lubezki and Burton contemplated shooting the film in black and white, and in old square Academy ratio. When that proved unfeasible, they opted to apply bleach bypass to desaturate the image and increase the color black.[16] Burton and Lubezki intentionally planned the over-dependency of smoke and soft lighting to accompany the film's sole wide-angle lens strategy. Lubezki also used Hammer horror[33] and Mexican Luchador films from the 1960s, such as Santo Contra los Zombies and Santo vs. las Mujeres Vampiro.[15] Lighting effects increased the dynamic energy of the Headless Horseman, while the contrast of the film stock was increased in post-production to add to the monochromatic feel.[33]

Leavesden Studios, a converted airplane factory, presented problems because of its relatively low ceilings. This was less of an issue for The Phantom Menace, in which set height was generally achieved by digital means. "Our visual choices get channeled and violent," Heinrichs elaborated, "so you end up with liabilities that you tend to exploit as virtues. When you've got a certain ceiling height, and you're dealing with painted backings, you need to push atmosphere and diffusion."[25] This was particularly the case in several exteriors that were built on sound stages. "We would mitigate the disadvantages by hiding lights with teasers and smoke."[25]

Visual effects

editThe majority of Sleepy Hollow's 150 visual effects shots were handled by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM),[34] while Kevin Yagher supervised the human and creature effects. Framestore also assisted on digital effects, and The Mill handled motion control photography.[35] In part a reaction to the computer-generated effects in Mars Attacks!, Burton opted to use as limited an amount of digital effects as possible.[16] Ray Park, who served as the Headless Horseman stunt double, wore a blue ski mask for the chroma key effect, digitally removed by ILM.[20] Burton and Heinrichs applied to Sleepy Hollow many of the techniques they had used in stop motion animation on Vincent—such as forced perspective sets.[32]

The windmill was a 60-foot-tall forced-perspective exterior (visible to highway travellers miles away), a base and rooftop set and a quarter-scale miniature. The interior of the mill, which was about 30 feet high and 25 feet wide, featured wooden gears equipped with mechanisms for grinding flour. A wider view of the windmill was rendered on a Leavesden soundstage set with a quarter-scale windmill, complete with rotating vanes, painted sky backdrop and special-effects fire. "It was scary for the actors who were having burning wood explode at them," Heinrichs recalled. "There were controls in place and people standing by with hoses, of course, but there's always a chance of something going wrong."[36] For the final shot of the burning mill exploding, the quarter-scale windmill and painted backdrop were erected against the outside wall of the "flight shed", a spacious hangar on the far side of Leavesden Studios. The hangar's interior walls were knocked down to create a 450-foot run, with a 40-foot width still allowing for coach and cameras. Heinrichs tailored the sets so cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki could shoot from above without seeing the end of the stage.[36]

Actor Ian McDiarmid, who portrayed Dr. Lancaster, had just finished another Leavesden production with Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace. He compared the aesthetics of the two films, stating that physical sets helped the actors get into a natural frame of mind. "Having come from the blue-screen world of Star Wars it was wonderful to see gigantic, beautifully made perspective sets and wonderful clothes, and also people recreating a world. It's like the way movies used to be done"[27]

Musical score

edit| Sleepy Hollow: Music from the Motion Picture | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | November 16, 1999 |

| Length | 67:52 |

| Label | Hollywood Records |

The film score was written and produced by Danny Elfman. It won the Golden Satellite Award and was also nominated by the Las Vegas Film Critics.

Release

editMarketing

editTo promote Sleepy Hollow, Paramount Pictures featured the film's trailer at San Diego Comic-Con in August 1999.[37] The following October, the studio launched a website, which Variety described as being the "most ambitious online launch of a motion picture to date."[38] The site (sleepyhollowmovie.com) offered visitors live video chats with several of the filmmakers hosted by Yahoo! Movies and enabled them to send postcards, view photos, trailers and a six-minute behind-the-scenes featurette edited from a broadcast that aired on Entertainment Tonight. Extensive tours of 10 sets were offered, where visitors were able to roam around photographs, including the sets for the entire town of Sleepy Hollow, forest, church, graveyard and covered bridge. Arthur Cohen, president of worldwide marketing for Paramount, explained that the "Web-friendly" pre-release reports[38] from websites such as Ain't It Cool News and Dark Horizons[39][40] encouraged the studio to create the site.[38] In the weeks pre-dating the release of Sleepy Hollow, a toy line was marketed by McFarlane Toys.[41] Simon & Schuster also published The Art of Sleepy Hollow (ISBN 0671036572), which included the film's screenplay and an introduction by Tim Burton.[42] A novelization, also published by Simon & Schuster, was written by Peter Lerangis.[43]

Box office

editSleepy Hollow was released in the United States on November 19, 1999, in 3,069 theaters, grossing $30,060,467 in its opening weekend[7] at the No. 2 spot behind The World Is Not Enough.[44] It would drop into fourth place behind the latter film, Toy Story 2 and End of Days the following weekend.[45] Sleepy Hollow eventually earned $101,068,340 in domestic gross, and $106 million in foreign sales, coming to a worldwide total of $207,068,340.[6]

Home media

editParamount Home Video first released Sleepy Hollow on DVD and VHS in the United States on May 23, 2000.[46] The HD DVD release came in July 2006,[47] while the film was released on Blu-ray two years later, in June 2008.[48] An unofficial video game adaptation of the film titled Cursed Fates: The Headless Horseman was released by Fenomen Games and Big Fish Games on January 6, 2013.[49] For the 20th anniversary, Paramount Home Entertainment released a Blu-ray digibook with a photobook containing the original story on September 24, 2019.[50]

Reception

editFilm review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 70% of critics gave Sleepy Hollow a positive review based on 123 reviews with an average rating of 6.3/10. The site's critics consensus states, "It isn't Tim Burton's best work, but Sleepy Hollow entertains with its stunning visuals and creepy atmosphere."[51] Metacritic, another review aggregator, assigned the film a weighted average score of 65 out of 100 based on 35 reviews from mainstream critics, considered to be "generally favorable".[52] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B−" on an A+ to F scale.[53]

Roger Ebert gave it 3.5 stars out of 4 and said: "This is the best-looking horror film since Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula". He praised Johnny Depp's performance and Tim Burton's methods of visual design. "Johnny Depp is an actor able to disappear into characters," Ebert continued, "never more readily than in one of Burton's films."[54] Richard Corliss wrote, in his review for Time, "Burton's richest, prettiest, weirdest [film] since Batman Returns. The simple story bends to his twists, freeing him for an exercise in high style."[55]

David Sterritt of The Christian Science Monitor gave praise to filmmaking and the high-spirited acting of cast, but believed Andrew Kevin Walker's writing was too repetitious and formulaic for the third act.[56]

Owen Gleiberman from Entertainment Weekly wrote Sleepy Hollow is "a choppily plotted crowd-pleaser that lacks the seductive, freakazoid alchemy of Burton's best work." Gleiberman compared the film to The Mummy, and said "it feels like every high-powered action climax of the last 10 years. Personally, I'd rather see Burton so intoxicated by a movie that he lost his head."[57]

Andrew Johnston of Time Out New York wrote "[l]ike the best of Burton's films, Sleepy Hollow takes place in a world so richly imagined that, despite its abundant terrors, you can't help wanting to step through the screen."[58]

Mick LaSalle, writing in the San Francisco Chronicle, criticized Burton's perceived image as a creative artist. "All Sleepy Hollow has going for it is art direction, and even in that it falls back on cliché."[59]

Jonathan Rosenbaum from the Chicago Reader called Sleepy Hollow "a ravishing visual experience, a pretty good vehicle for some talented American and English actors," but concluded that the film was a missed opportunity to depict an actual representation of the short story. "Burton's fidelity is exclusively to the period feeling he gets from disreputable Hammer horror films and a few images culled from Ichabod and Mr. Toad. When it comes to one of America's great stories, Burton obviously couldn't care less."[60]

Accolades

edit| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[61] | March 26, 2000 | Best Art Direction | Rick Heinrichs, Peter Young | Won |

| Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Colleen Atwood | Nominated | ||

| British Academy Film Awards[62] | April 9, 2000 | Best Production Design | Rick Heinrichs | Won |

| Best Costume Design | Colleen Atwood | Won | ||

| Best Visual Effects | Jim Mitchell, Kevin Yagher, Joss Williams, Paddy Eason | Nominated | ||

| Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films[63] | June 6, 2000 | Best Horror Film | Scott Rudin, Adam Schroeder | Nominated |

| Best Director | Tim Burton | Nominated | ||

| Best Writing | Andrew Kevin Walker | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor | Johnny Depp | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress | Christina Ricci | Won | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Christopher Walken | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Miranda Richardson | Nominated | ||

| Best Music | Danny Elfman | Won | ||

| Best Costume | Colleen Atwood | Nominated | ||

| Best Make-up | Kevin Yagher, Peter Owen | Nominated | ||

| Best Special Effects | Jim Mitchell, Kevin Yagher, Joss Williams, Paddy Eason | Nominated | ||

| American Society of Cinematographers[64] | February 20, 2000 | Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Nominated |

| Art Directors Guild[65] | February 8, 2000 | Excellence in Production Design for a Feature Film | Rick Heinrichs, Les Tompkins, John Dexter, Kevin Phipps, John Wright Stevens, Ken Court, Andrew Nicholson, Bill Hoes, Julian Ashby, Gary Tompkins, Nick Navarro | Won |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards | 1999 | Best Art Direction | Rick Heinrichs | Won |

| Best Costume Design | Colleen Atwood | Won | ||

| Best Sound | Nominated | |||

| Best Visual Effects | Nominated | |||

| BMI Film & Television Awards | December 8, 2014 | BMI Film Music Award | Danny Elfman | Won |

| Blockbuster Entertainment Awards[66] | May 9, 2000 | Favorite Actor – Horror | Johnny Depp | Won |

| Favorite Actress – Horror | Christina Ricci | Won | ||

| Favorite Supporting Actress – Horror | Miranda Richardson | Won | ||

| Favorite Supporting Actor – Horror | Marc Pickering | Nominated | ||

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards[67] | December 12, 1999 | Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Won |

| Chicago Film Critics Association[68] | March 13, 2000 | Best Cinematography | Nominated | |

| Costume Designers Guild[69] | February 25, 2000 | Excellence in Period/Fantasy Costume Design for Film | Colleen Atwood | Won |

| Hollywood Makeup Artist and Hair Stylist Guild Awards[70] | March 19, 2000 | Best Character Makeup – Feature | Kevin Yagher, Peter Owen, Liz Tagg, Paul Gooch | Won |

| International Film Music Critics Association[71] | February 23, 2012 | Best Archival Release of an Existing Score | Danny Elfman (also for Pee-wee's Big Adventure, Beetlejuice, Batman, Edward Scissorhands, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Big Fish, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Corpse Bride and Alice in Wonderland) | Won |

| International Film Music Critics Association[72] | February 4, 1999 | Film Score of the Year | Danny Elfman | Nominated |

| International Horror Guild[73] | May 12, 2000 | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists[74] | May 12, 2000 | Best Foreign Director | Tim Burton | Nominated |

| Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards[75] | January 18, 2000 | Best Score | Danny Elfman | Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Colleen Atwood | Nominated | ||

| Best Production Design | Rick Heinrichs | Won | ||

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[76] | December 12, 1999 | Won | ||

| MTV Movie Awards[77] | June 5, 2000 | Best Villain | Christopher Walken | Nominated |

| Motion Picture Sound Editors[78] | December 15, 1999 | Best Sound Editing – Effects & Foley | Skip Lievsay, Thomas W. Small, Sean Garnhart, Lewis Goldstein, Paul Urmson, Craig Berkey, Richard L. Anderson, John Pospisil, Michael Dressel, Scott Curtis, Matthew Harrison, Tammy Fearing | Nominated |

| National Society of Film Critics[79] | January 8, 2000 | Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Nominated |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards[80] | January 9, 2000 | Best Cinematographer | Runner-up | |

| Online Film & Television Association[81] | January 12, 2000 | Best Original Score | Danny Elfman | Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Nominated | ||

| Best Production Design | Rick Heinrichs, Ken Court, John Dexter, Andy Nicholson, Kevin Phipps, Leslie Tomkins, Peter Young | Won | ||

| Best Costume Design | Colleen Atwood | Nominated | ||

| Best Makeup and Hairstyling | Kevin Yagher, Peter Owen, Liz Tagg, Paul Gooch, Susan Parkinson, Bernadette Mazur, Tamsin Dorling | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound Mixing | Lee Dichter, Robert Fernandez, Skip Lievsay, Frank Morrone | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound Effects | Skip Lievsay | Nominated | ||

| Best Visual Effects | James Mitchell, Kevin Yagher, Joss Williams, Paddy Eason | Nominated | ||

| Best Official Film Website | www.sleepyhollow.com | Nominated | ||

| Online Film Critics Society[82] | January 2, 2000 | Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Won |

| Santa Fe Film Critics Circle Awards[83] | January 9, 2000 | Won | ||

| Satellite Awards[84] | January 16, 2000 | Best Actor – Musical or Comedy | Johnny Depp | Nominated |

| Best Original Score | Danny Elfman | Won | ||

| Best Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki | Won | ||

| Best Art Direction | Ken Court, John Dexter, Rick Heinrichs and Andy Nicholson | Won | ||

| Best Costume Design | Colleen Atwood | Won | ||

| Best Editing | Chris Lebenzon | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound | Gary Alpers, Skip Lievsay, Frank Morrone | Won | ||

| Best Visual Effects | Jim Mitchell, Joss Williams | Nominated | ||

| Teen Choice Awards[85] | August 6, 2000 | Film – Choice Actress | Christina Ricci | Nominated |

| Young Artist Award[86] | March 19, 2000 | Best Performance in a Feature Film: Leading Young Actress | Nominated |

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Headless Horseman – Nominated Villain

Reboot

editOn June 10, 2022, Paramount announced plans for a reboot of Sleepy Hollow with Lindsey Beer in talks to write and direct it.[87]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Sleepy Hollow (1999)". Lumiere. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ Harris, Dana (December 17, 2001). "Mandalay on road with Summit". Variety. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow (1999)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow". letterboxd.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Sleepy Hollow (1999)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ a b "Sleepy Hollow (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Deming, Mark. "Sleepy Hollow (1999)". AllMovie. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ^ Rinaldi, Ray Mark (March 27, 2000). "Crystal has a sixth sense about keeping overhyped, drawn-out Oscar broadcast lively". Off the Post-Dispatch. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. p. 27. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Freydkin, Donna (November 16, 1999). "Burton and Depp: Wide awake in 'Sleepy Hollow'". CNN. Archived from the original on January 18, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Burton 2006, pp. 161–169.

- ^ a b c Shapera, Todd (October 24, 1999). "The Legend Continues; In a Cluster of New Films This Fall, Washington Irving's Classic Rides Again". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nashawaty, Chris (November 19, 1999). "Sleepy Hollow: A Head of its Time". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Newman, Kim (January 2000). "The Cage of Reason". Sight and Sound.

- ^ a b c d e f Salisbury, Mark (November 1999). "Graveyard Shift". Fangoria.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burton 2006, pp. 177–183.

- ^ a b "Burton eyes 'Hollow'; Rodman wrestles". Variety. June 17, 1998. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Seymour, Gene (November 17, 1998). "Headless In Hollywood". Newsday.

- ^ a b Weinraub, Bernard (November 19, 1999). "At the Movies". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Mills, David (February 2000). "One on One: Tim Burton". Total Film. pp. 50–56.

- ^ Hochman, David (July 9, 1998). "Brad Pitt may star in the new Tim Burton film". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Hindes, Andrew (July 15, 1998). "Depp to ride in 'Hollow'". Variety. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Blackwelder, Rob (November 12, 1999). "Deppth Perception". SPLICEDwire.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Salisbury, Mark (December 17, 1999). "The American Nightmare". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Calhoun, John (November 1999). "Headless in Sleepy Hollow". Entertainment Design.

- ^ "From the drafting board: Rick Heinrichs". Variety. February 23, 2000. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Wolf, Matt (April 11, 1999). "'Sleepy Hollow,' on the Thames". The New York Times.

- ^ Hindes, Andrew (November 11, 1998). "Mandalay's 'Sleepy'". Variety. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "TV & Film Locations". Culden Faw Estate. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "Shooting in town". Variety. November 11, 1999. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow". KeithShortSculptor.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2008. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ^ a b Burton 2006, pp. 170–176.

- ^ a b "Cinematographer's Journal". Variety. January 17, 2000. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Graser, Marc (January 2, 2000). "Seven pics make the cut in Oscar f/x nominee race". Variety. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Karl (September 1999). "More ILM Work Will Be In Theaters This Year". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on December 22, 2001. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Abbott, Denise (February 29, 2000). "Entertainment By Design". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Amidi, Amid (September 1999). "San Diego Comic-Con '99: More Than Fat, Sweaty Guys". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c Graser, Marc (November 1, 1999). "Par gets peppy with 'Sleepy' online". Variety. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Graser, Marc (October 19, 1999). ".Com before storm". Variety. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ McWeeny, Drew (August 26, 1998). "Moriarty Reports On Tim Burton's Sleepy Hollow". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on May 23, 2005. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Kilmer, David (November 19, 1999). "McFarlane Toys releases Sleepy Hollow figures". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Walker, Andrew Kevin (1999). "The Art of Sleepy Hollow". Pocket Books. ISBN 0671036572.

- ^ Lerangis, Peter (1999). "Sleepy Hollow: A Novelization". Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671036653.

- ^ Hayes, Dade (November 21, 1999). "B.O. shaken, stirred by Bond". Variety. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Lyman, Rick (November 29, 1999). "Those Toys Are Leaders In Box-Office Stampede". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow". Amazon. May 23, 2000. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow (HD DVD)". Amazon. July 25, 2006. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow (Blu-ray)". Amazon. June 3, 2008. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Fenomen Games. "Cursed Fates: The Headless Horseman Collector's Edition". Big Fish Games. Big Fish Games, Inc. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Watch Sleepy Hollow | DVD/Blu-ray or Streaming". Paramount Movies. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ "Sleepy Hollow Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 19, 1999). "Sleepy Hollow". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (November 22, 1999). "Tim Burton's Tricky Treat". Time. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Sterritt, David (November 19, 1999). "New Releases". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on February 29, 2000. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (November 26, 1999). "Dead Heads". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Andrew (November 1999). "Sleepy Hollow". Time Out New York. p. 121.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (November 19, 1999). "'Sleepy Hollow' a Yawner". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (November 26, 1999). "Hollow Rendition [on Sleepy Hollow]". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 72nd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Film in 2000". BAFTA. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ "'Hollow' carves most Saturn Awards noms". Variety. March 15, 2000. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "The ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography". theasc.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2011.

- ^ "4th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards". adg.org. February 3, 2000. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "Blockbuster Entertainment Award winners". Variety. May 9, 2000. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ "Past Winners". BSFC. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Chicago Film Critics Awards 1999". FilmAffinity. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "Winners of the 2nd Annual Costume Designers Guild Awards". HitFix. February 25, 2000. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Ryfle, Steve (March 19, 2000). "Stars Praise Hollywood's Primping Pros". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "IFMCA Award nominations 2011". International Film Music Critics Association. February 9, 2012. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "1999 FMCJ Awards". International Film Music Critics Association. October 18, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "IHG Award Recipients". International Horror Guild. May 12, 2000. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "'Tulips' leads field for Italo crix awards". Variety. June 6, 2000. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "Previous Sierra Award Winners". Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards. January 18, 2000. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "'The Insider' Wins Top L.A. Film Critics Award". Los Angeles Times. December 12, 1999. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "1999 MTV Movie Awards". MTV. June 5, 2000. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "Contender-Skip Lievsay-Sound Mix/Edit-No Country". BTL News. December 15, 2006. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

- ^ "'Malkovich' and 'Topsy-Turvy' Tie for Critics' Prize". The New York Times. January 10, 2000. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "N.Y. crix tap 'Turvy' tops". Variety. December 16, 1999. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "1999: THE YEAR OF American Beauty". Online Film & Television Association. January 12, 2000. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "1999 Awards (3rd Annual)". Online Film Critics Society. January 2, 2000. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Santa Fe Film Critics Circle Awards". Santa Fe Film Critics Circle Awards. January 2, 2000. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "2000 4th Annual SATELLITE™ Awards". International Press Academy. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "The Teen Choice Awards 2000 – Movies". Fox.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2001. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "Twentyfirst Annual Young Artist Awards 1998–1999". Young Artist Awards. March 19, 2000. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (June 10, 2022). "Lindsey Beer To Write And Direct A Reboot Of 'Sleepy Hollow' For Paramount". Deadline. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

Further reading

edit- Burton, Tim (2006). Salisbury, Mark (ed.). Burton on Burton. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571229260.

External links

edit- Sleepy Hollow at IMDb

- Sleepy Hollow at the TCM Movie Database

- Sleepy Hollow at AllMovie

- Sleepy Hollow at Rotten Tomatoes

- Sleepy Hollow at Box Office Mojo

- Sleepy Hollow at Metacritic

- Tim Burton interview by Charlie Rose

- Pizzello, Stephen (December 1999). "Galloping Ghost". American Cinematographer. Vol. 80. pp. 38–53. (Archived)

- Kenny, Tom (December 1, 1999). "Sound FX for 'Sleepy Hollow': Heads Will Roll, Horses Will Run". Mix. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012.