This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) |

Crouch End is an area of North London, approximately five miles (8 km) from the City of London in the western half of the borough of Haringey. It is within the Hornsey postal district (N8). It has been described by the BBC as one of "a new breed of urban villages" in London.[2] In 2023, it was voted the best place to live in London by the Sunday Times, saying "A creative edge and friendly neighbours give this lofty northern enclave social capital in the capital".[3]

| Crouch End | |

|---|---|

Crouch End Broadway | |

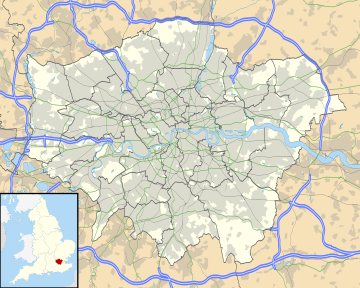

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 12,395 (2011 Census. Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ295885 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | N8 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Location

editCrouch End lies between Harringay to the east; Muswell Hill to the north-west; Hornsey to the north; Wood Green to the north-east; Finsbury Park, Stroud Green and Archway to the south; and Highgate to the west. It is located 4.6 miles (7.4 km) north of Charing Cross and 5.1 miles (8.2 km) from the City of London.

Toponymy

editThe name Crouch End is derived from Middle English. A "crouch" meant cross while an "end" referred to an outlying area.[4][5] Some think that this refers to the borders of the parish, in other words, the area where the influence of the parish ends.

Its name has been recorded as Crouchend (1465), Crowchende (1480), the Crouche Ende (1482), and Crutche Ende (1553).[6] In 1593, it was recorded as "Cruch End".[7]

History

editCrouch End was the junction of four locally important roads. A wooden cross was erected at the junction of these roads, roughly where the Clock Tower now stands, and a small settlement developed around it. Crouch End developed as an early centre of cultivation for Hornsey, and was where the farmsteads seem to have been grouped.[8]

From the later part of the eighteenth century, Crouch End became home to wealthy London merchants seeking refuge from the City. However, the area remained rural in character until around 1880.[9] The development of the railway changed the area significantly. By 1887 there were seven railway stations in the area.

Although the first patch of urbanisation along Park Road (Maynard Street until c1870) was distinctly working-class in character, by the end of the 19th century, the large merchants' villas had been replaced by urban middle-class housing and Crouch End had become a comfortable middle-class London suburb with a varied and popular range of shops.

Until 1965 Crouch End was part of the Municipal Borough of Hornsey and that body's forerunners. In 1965, when local government in London was reorganised, Hornsey merged with the boroughs of Wood Green and Tottenham, and Crouch End became part of the London Borough of Haringey.

In the post-war years, the London-wide provision of social housing led to the demolition of the Park Road housing development and its replacement with council homes. Many of the older houses in the area lay empty post-war and many were bought cheaply by speculative landlords who then let them out to the growing student populations of the Mountview and Hornsey Art College. The area became known as bedsit land into the early 1980s, until rising house prices changed the social profile of the area and progressively wealthier residents moved in.

Demographics

editThere is no single figure that provides the demographic profile for Crouch End. As defined by the recent public-council conversation around the setting up of the Crouch End neighbourhood Forum, the neighbourhood is made up of parts of four wards.[10] Between a half and two thirds of the area is formed by Crouch End ward. Its demographics in the 2011 census were as follows:

British 61.1%,[11] White Other 17.5%, Irish 3.4%, Indian 1.6%, Black African 1.5%.

Christian 38.4%, Jewish 4.2%, Muslim 3.1% (no religion 41.2%).[12]

Notable buildings

editHornsey Town Hall

editAmong its more prominent buildings is the modernistic Hornsey Town Hall, built by the Municipal Borough of Hornsey as their seat of government in 1933–35.[13] It is now a Grade II* listed building, one of about 21,767. The architect was the New Zealand-born Reginald Uren. The interior and exterior have been used several times as a location by the BBC series The Hour, written by Abi Morgan, and other TV and films, including a scene in The Crown.[14]

Queen and the Kinks have both played at the Hornsey Town Hall when it was a major London venue for bands. The HTH was used as a set in the Queen film Bohemian Rhapsody.

The building is currently undergoing renovation and conversion into a hotel, apartments, restaurant and a contemporary arts centre by the Far East Consortium. Completion is expected to be by Summer 2024.

Clocktower

editThe red-brick Clock Tower has become a much-loved icon of Crouch End. Designed by the architect Frederick Knight, it was originally built as a memorial to Henry Reader Williams[15] in 1895.[16] Williams was chairman of the local authority of Hornsey from 1880 to 1894, and played a key part in shaping the district, in particular campaigning against developers for the preservation of Highgate Wood and Queen's Wood. He also paved the way for the purchase of Alexandra Palace and Park by a consortium of local authorities in 1901. After Williams's retirement the newly designated Hornsey Urban District Council decided to erect a clock tower to celebrate his achievements.

Out of the estimated cost of £1200, £900 was raised by public subscription. On 23 June 1895 a ceremony was held for its unveiling. The Broadway was hung with flags, and the Tower connected to nearby houses with festoons. Over a thousand people assembled, and at noon the Earl of Stafford, Lord-Lieutenant of Middlesex, released a blue ribbon hanging from the belfry and the clock struck its first notes. The bronze sculpture of the head of Williams was created by Alfred Gilbert, who also designed Eros in Piccadilly Circus.[17]

Although closed to the public, it is now used at Christmas for a Santa's Grotto.

Crouch End Hippodrome

editThe Crouch End Hippodrome originally opened on Tottenham Lane in July 1897 as the Queen's Opera House with a production of The Geisha. The theatre was leased initially by H. H. Morell and Frederick Mouillot (who at the time owned another 17 theatres between them). It held an audience of 1,500 people. In 1907, it was renamed the Hippodrome and became a popular music hall. During a bombing raid in 1940 it was very badly damaged. It is now a Virgin Active gym.

Hornsey College of Art

editIn 1880 an art school was established by Charles Swinstead, an artist and teacher who lived at Crouch End. It became "an iconic British art institution, renowned for its experimental and progressive approach to art and design education". In May 1968, as Hornsey College of Art, it was occupied by students as a protest against the ideology of art education and teaching in Britain.[18] The occupation, soon joined by others around the country, and linked with similar events in Paris, offered a major critique of the education system at the time.[19]

After the authorities regained control, known as the "night of the dogs", sympathetic lecturers and students who had taken part (including Tom Nairn and Kim Howells) were dismissed. Later the college was merged with Middlesex Polytechnic, now University, in the 1970s. Subsequently, it was relocated to a Middlesex campus at Alexandra Palace and the lease of the building taken over by the TUC, which used it as its national training centre. In 2005 Haringey Council took it over, extending and converting the building in order to enlarge Coleridge Primary School.

The Queens Pub

editOne of the early Edwardian pubs-with-hotel, the Queen's was built in 1899–1902 by developer John Cathles Hill. The pub's Art Nouveau decor windows survive. Its larger sister pub, the Salisbury Hotel (now The Salisbury) in Harringay has some similar architectural details.

Dunns Bakery

editPurpose built in 1850 to be a bakery, Dunns Bakery at 6 The Broadway is most likely the oldest retail building within Crouch End. At the top of the front facade one can see a gilded wheat sheaf which bears the initials of the builder, 'WM' Originally the gates located to the right of the store led to a yard area where the stables were located to house the horses used for deliveries. The stables had been damaged in the Blitz during a night time raid, and have since been rebuilt, expanding the bakery area.

The bakery continues to produce on site to this day, and is run by a sixth generation baker.

Education

editThere are three state secondary schools serving the N8 Crouch End area. Highgate Wood School in Montenotte Road is a nine form entry mixed school. Highgate Wood School was the senior school to the former Crouch End School based on the corner of Wolseley Road and Park Road, opposite the Maynard Arms. Hornsey School for Girls in Inderwick Road is the only single sex school in N8. In Hornsey, there is the Greig City Academy (formerly St David and St Katherines). Further away Heartlands High School which lies between Wood Green and Alexandra Palace was opened by Haringey in 2010; despite not being in Crouch End it is close enough to provide additional provision. St Thomas More Catholic School, Wood Green is the only Roman Catholic secondary school in the London Borough of Haringey.[20]

Over 6,000 children school in the area, approx 2,300 in primary schools and 3,700 in secondary schools (11-18).

Kestrel House is an independent special school for pupils with autistic spectrum conditions and additional learning and behavioural needs. The vast majority of pupils are referred by local authorities in London and the Home Counties who pay the fees.[citation needed] It is housed in the former Mountview Theatre School premises at the north end of Crouch Hill -the end nearest Crouch End Broadway. Also in the independent (fee paying sector) are Highgate School and Channing School, both used by parents in Crouch End but located in Highgate.

There are a number of primary schools serving Crouch End (seven in total within the N8 postcode): Weston Park, Rokesly School, Coleridge Primary School at the top of Crouch End Hill near the border with Islington, St Aidans in Stroud Green (not N8), St Gildas and St Peter-in Chains, just off Crouch Hill and St Mary's in Hornsey. Campsbourne Primary School on Nightingale Lane, North Harringay Primary School on Falkland Road and Ashmount Primary School. Ashmount was until December 2012 on the south side of Hornsey Lane, in Islington and in the N19 postal district, but only meters from Haringey. (The border between Haringey and Islington runs down Hornsey Lane.) The school moved January 2013 to a new building in Crouch Hill Park adjacent to the Parkland Walk in N8.

There are many nursery schools in the area, including Bright Horizons, Creative Explorers, Starshine, Keiki and MTO.

Library provision

editHornsey Library is located on Haringey Park, N8. The Grade II listed building is on a site adjoining the south side of Hornsey Town Hall. It has recently had a major refurbishment, including the fountain area, but due to RACC the main library building has a temporary crash desk, so full of scaffolding, while the roof is being replaced.

The library contains a large book stock, DVDs, provides free access to the Internet, meeting rooms for adult education classes, the Original Gallery for art exhibitions, literary groups and performers. There is also a children's library, where events for pre-school children take place.

Permanent artwork includes the engraved Hornsey Window by Fred Mitchell, and a bronze sculpture outside by Huxley-Jones. The library contains the Community and Youth Music Library, one of largest collections of music sets in the country. Owned by a charitable company, it was started over 100 years ago and is now located semi-permanently at Hornsey Library.

Since 2022 it has been one of 4 centres of the Crouch End Festival, and the Crouch End Literary Festival, with events covering arts, culture, comedy, music, drama, spoken word and live street art.

Parks

editCrouch End does not officially have a park. The two main parks in the area are Stationers' Park (in Hornsey Vale) and Priory Park (in Hornsey). To the immediate west, lies Highgate Wood, and the adjacent Queen's Wood, as well as a large expanse of playing fields. To the north is Alexandra Park and to the south Finsbury Park. The Parkland Walk, a former railway line, makes a circuitous connection part of the way between these two parks and is in both Haringey and Islington.

Local Civic Society

editCrouch End Neighbourhood Forum

editThe Neighbourhood Forum, set up in response to the government initiatives under the heading "localism". The forum is formally recognised by the London Borough of Haringey[21] as representative of Crouch End. One of the first tasks of the forum was to attempt to define the boundaries of Crouch End.[22] The forum's main task is to produce a neighbourhood plan.[23]

Hornsey Historical Society

editFounded in 1971, the HHS has over 400 members and is based in the old school house on the boundary between Hornsey and Crouch End by Holy Innocents.[24] The HHS was originally formed to draw attention to and conserve historic buildings in Hornsey, and expanded to research, preserve and promote the history of the parish of Hornsey, and from 1983 included the area covered by the parliamentary constituency of Hornsey and Wood Green. They have over 21,000 items including articles, books, documents & manuscripts, local newspapers, maps, photographs, postcards and video memories. They also sell books on the local history and organise talks.

Local arts scene

editCrouch End has a long association with creativity, and most famous for the Hornsey College of Art which was regarded as one of the best art colleges in the UK in the 60s but also famous for the 1968 sit-in that challenged the government's policy on removing art schools' independence. Since the 1970s, when it was a cheap area to love, artists, musicians, film and TV makers, animators and performers moved to the area. A 2016 article in the Evening Standard stated that estate agents liked to call the area "London's Creative Village", and that "ever since the heady days of student protests at nearby Hornsey College of Art in 1968, Crouch End has had an arty reputation".[25]

Cinema

editCrouch End has two cinemas, the independent Art House and the Crouch End Picturehouse. There will be a third cinema in the Hornsey Town Hall when it is finished.

Comedy

editCrouch End is home to the Kings Head, London's oldest comedy venue.

Music

editCrouch End is the home of the symphonic choir, Crouch End Festival Chorus. The choir has worked with many classical and popular music artists including Ennio Morricone, Noel Gallagher, Andrea Bocelli, Katherine Jenkins. It has recorded with Lesley Garrett, Bryn Terfel, Ray Davies, Alfie Boe, EMI Classics and Classic FM, performed at The Proms in the Royal Albert Hall on several occasions and recorded works for film, television and sound track recording. Amongst those is the soundtrack for Doctor Who. It also commissions works from modern composers on its own account.

It also has a thriving blues scene and a strong associations with famous bands, including the Kinks, Dave Stewart & Annie Lennox (Tourists/Eurythmics), Bombay Bicycle Club and Pink Floyd who lived in the area in the '60s and played at the Hornsey College of Art.

It has two notable recording studios, the Church Studios (see below) and KONK (founded by the Kinks) where many bands have recorded including the Bay City Rollers, Thin Lizzy, the Bee Gees, Bombay Bicycle Club, and The Arctic Monkeys.

The Church Studios and Bob Dylan

editThe Church Studios is a recording studio located in the former Park Chapel in Crouch End. The Chapel was turned into a studio in 1984 by Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox of Eurythmics, who used it to record Eurythmics' sophomore album Sweet Dreams.[26] David Gray acquired ownership in 2004 before UK leading music producer Paul Epworth bought and refurbished the studio in 2013. It has since been used by notable artists such as Adele, U2, Bob Dylan, Radiohead, Annie Lennox, Depeche Mode, Robert Plant, Patti Smith, Elvis Costello, Lana Del Rey, Tom Jones, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Florence + The Machine, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, Mumford and Sons, Seal, Spiritualized, The Stones Roses and many more.

In the early 1980s part of the old church on Crouch Hill was converted for use as a studio by Bob Bura and John John Hardwick, the animators who worked on Camberwick Green, Captain Pugwash and Trumpton. It was named The Church Studios, and in the 1990s the space was rented to Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox of the Eurythmics (but at the time was in the Tourists). Dave and Annie worked and rehearsed in the Spanish Moon record shop, and lived in the flat above from 76 to 80, opposite what is now the Co-op.[citation needed]

In the 1990s Bob Dylan worked on an album in the studio, and became so fond of the area he looked for a property in Crouch End. He was a regular at the now-closed Shamrat Indian restaurant.[27]

Crouch End Festival

editThe Crouch End Festival was launched in May 2012 by Chris Arnold, Robin Stevenson and Marice Cumber.[28] It originally started as a Facebook site, Crouch End Creatives but is now run by London Community Arts CIC, a not for profit organisation that is staffed by volunteers (Directors Chris Arnold, Chris Currer, Amanda Carrara). It covers Crouch End, Hornsey and Stroud Green and includes art exhibitions, drama, dance, film, poetry, photography, fringe, music of all kinds, an outdoor cinema, (introduced by Peter Bradshaw). The festival is one of London's biggest community arts festivals and features over 200 artists, plus 14 schools, 6 churches and numerous community groups across over 60 venues and was not described in the Ham & High Broadway as "London's own mini Edinburgh Festival".[citation needed] The next festival is June 2025.

The Festival team also runs the Crouch End Literary Festival (with Dave Cohen) and numerous events at Halloween, Easter and Christmas. They also manage two venues, 'The Intmate Space' in St Mary's Tower, and the Holy Eye in Holy Innocents church and organise üF-Beat Fringe Music Club and the Tower Music Festival. London Community Arts also acts as a consultancy and advises community groups, other festival organisers, commercial organisations and councils.

Arts scene urban legends

edit- According to legend, in the 1990s Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics invited Bob Dylan to drop into his Crouch Hill recording studio any time he wanted to. It is said that Dylan took him up on his offer, but the taxi driver dropped him off on the adjacent Crouch End Hill. Dylan knocked on the door of the supposed home of Dave Stewart and asked for "Dave". By coincidence, the plumber who lived there was also called Dave. He was told that Dave was out, and would he like to wait and have some tea? Twenty minutes later the plumber returned and asked his wife whether there were any messages. "No," she said, "but Bob Dylan's in the living room having a cup of coffee".[29]

- The area gives its name to and is the setting for a short story of the supernatural by Stephen King. The writer and his wife, Tabitha, were invited to dinner by his friend Peter Straub, whose house is in Crouch End.[30] En route to Straub's house, they got lost, which was the inspiration for "Crouch End".[31] The story was later adapted as an episode of Nightmares and Dreamscapes: From the Stories of Stephen King.

- In claim seen only on local estate agents' websites, it is said that Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy once performed at the Crouch End Hippodrome and that they stayed at the Queen's Hotel (now the Queen's Pub).[dubious – discuss]

- Artist Richard Hamilton is said to have taken visitor Marcel Duchamp to the Queen's Pub. [dubious – discuss]

Notable residents

editSurrounding neighbourhoods

editTransport

editRail

editHornsey Station is 0.7 miles (1.1 km) to the north of Crouch End.[32] Harringay Station is 1.1 miles (1.8 km) to the east.[32] 1.4 miles (2.3 km) to the south is Finsbury Park Station.[32] All three are managed and served by Great Northern.

The Gospel Oak to Barking line runs to the south of Crouch End.[33] London Overground trains running along the line call at Crouch Hill station, 0.7 miles (1.1 km) from the centre of Crouch End.[32] The London Overground links the area directly to Upper Holloway and Gospel Oak in the west, and to Harringay, South Tottenham, Walthamstow, and Barking in the east.[34]

Crouch End is not directly connected to the tube network, but nearby stations include:

Bus

editLondon Buses routes 41, 91, W3, W5, and W7 run through Crouch End.

Cycling and walking

editThe Parkland Walk is a shared use path that runs along the southern rim of Crouch End; it follows the course of the railway line that ran between Finsbury Park and Alexandra Palace, through Stroud Green, Crouch End, Highgate and Muswell Hill.

The path runs predominantly in a cutting through the former Crouch End railway station. Step-free access to Parkland Walk can be found near the summit of Crouch Hill, with access ramps provided for cyclists, wheelchair users and pushchairs.[35]

The Parkland Walk is part of the Capital Ring route, which is signposted.[36]

See also

edit- Hornsey (parish) for the ecclesiastical and local government unit of which Crouch End was part from medieval times to 1867

- Municipal Borough of Hornsey for the local government unit of which Crouch End was part from 1903 to 1965

- Stephen King short horror/supernatural story dramatised for television Crouch End with reference to local disused railway viaduct

References

edit- ^ "Haringey Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ "BBC Four - Pubs, Ponds and Power: The Story of the Village, Series 1, London". BBC. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Crouch End named best place to live in London 2023". 24 March 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "How London's Hills Got Their Names". Londonist. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "Crouch End, Haringey". Hidden London. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Mills, A. D. (2010). A Dictionary of London Place-Names. Oxford. pp. 67-68. ISBN 9780199566785.

- ^ "John Norden's map of Middlesex". Jonathan Potter Ltd. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ A P Baggs, Diane K Bolton, M A Hicks and R B Pugh, "Hornsey, including Highgate: Growth before the mid 19th century", in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 6, Friern Barnet, Finchley, Hornsey With Highgate, ed. T F T Baker and C R Elrington (London, 1980), pp. 107-111. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol6/pp107-111 [accessed 12 August 2018].

- ^ The transcribed 1829–1848 diaries of William Copeland Astbury describe in great detail London life of the period, including walks to Crouch End.[disputed – discuss]

- ^ Map showing Crouch End boundaries as defined for the establishment of the Crouch End Neighbourhood Forum and Copy of final application for the establishment of the forum

- ^ Ward Profile. Crouch End haringey.gov.uk

- ^ "Census 2011 map, London | UK Data Explorer".

- ^ Cherry, Bridget (2006). Civic Pride in Hornsey. London: Hornsey Historical Society.

- ^ "Haringey on Film - document from Haringey Council". Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ Henry Williams was a local wine merchant and local councillor who led the campaign to preserve Highgate Wood against threatened development.[citation needed]

- ^ Schwitzer, Joan (2002). Crouch End Clock Tower. Hornsey Historical Society.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Crouch End Clock Tower". Hornsey Historical Society. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ What happened at Hornsey in May 1968 — Nick Wright Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Students and staff of Hornsey College of Art (1969). The Hornsey Affair. Penguin Education. ISBN 9780140800968.

- ^ Official Site. Retrieved 26 March 2013

- ^ "About CENF". Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "the boundaries of Crouch End". Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "Our plan". Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ "Hornsey Historical Society Homepage". Hornsey Historical Society.

- ^ "Spotlight on Crouch End: property area guide". Evening Standard. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Bob Dylan recording studio 'could become flats'". BBC News. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Walker, Nick; Bennetto, Jason (15 August 1993). "No direction home? Dylan tries Crouch End". The Independent. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "Creative Festival of over 160 events". Crouch End Festival. 15 September 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ "Bob Dylan in Crouch End". expectingrain.com. 8 June 1997. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ "An Interview with Peter Straub (March, 2010)". Bookbanter. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Beahm, George (1 September 1998). Stephen King from A to Z: An Encyclopedia of His Life and Work. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 0836269144.

- ^ a b c d The measurement used is that given by the direction function on Google Maps between The Clocktower in Crouch End and the named station.

- ^ The definition of Crouch End borders are those given in the map submitted by the Crouch End Neighbourhood Forum and approved by the London Borough of Haringey

- ^ "London Overground" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "Home - The Friends of the Parkland Walk". Friends of the Parkland Walk. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "Capital Ring (Section 12)" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

External links

edit- Crouch End Festival

- Harringay Online, Busy locally-run community website used by N8, N4, N15 locals including a wealth of Hornsey history photos and well researched articles on Crouch End and Hornsey

- Photos tagged with "CrouchEnd" at Flickr

- Crouch End Neighbourhood Forum - Neighbourhood Plan

- An idiosyncratic history of 'Curious' Crouch End

- Very well researched and generally accurate history of Hornsey Borough: Steven Denford, Hornsey Past, Historical Publications, 2008.

- The best single-volume history of Crouch End, Ben Travers, The Book of Crouch End, Barracuda Books, 1990

- History of Crouch End - Hornsey Historical Society Books, articles, postcards, photographs, films etc.