This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

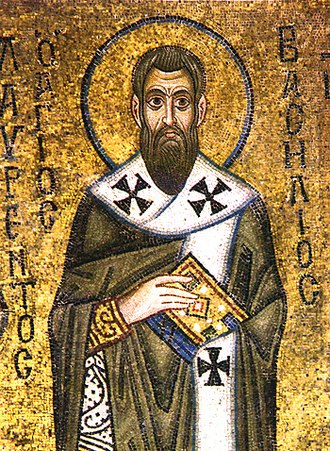

Basilian monks are Greek Catholic monks who follow the rule of Basil the Great, bishop of Caesarea (330–379). The term 'Basilian' is typically used only in the Catholic Church to distinguish Greek Catholic monks from other forms of monastic life in the Catholic Church. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, as all monks follow the Rule of Saint Basil, they do not distinguish themselves as 'Basilian'.

The monastic rules and institutes of Basil are important because their reconstruction of monastic life remains the basis for most Eastern Orthodox and some Greek Catholic monasticism. Benedict of Nursia, who fulfilled much the same function in the West, took his Regula Benedicti from the writings of Basil and other earlier church fathers.

Rule of St. Basil

editUnder the name of Basilians are included all the religious that follow the Rule of St. Basil.[1] The "Rule" is not intended to be a constitution like various Western monastic Rules; rather, it is a collection of his responses to questions about the ascetic life—hence the more accurate original name: Asketikon.

Attribution of the Rule and other ascetical writings that go under his name to Basil has been questioned. But the tendency is to recognize as his at any rate the two sets of Rules, the Greater Asketikon and the Lesser Asketicon. Probably the truest idea of his monastic system may be derived from a correspondence between him and Gregory Nazianzen at the beginning of his monastic life.

St. Basil drew up his Asketikon for the members of the monastery he founded about 356 on the banks of the Iris River in Cappadocia. Before forming this community St. Basil visited Egypt, Coele-Syria, Mesopotamia, and Palestine in order to see for himself the manner of life led by the monks in these countries. In the latter country and in Syria the monastic life tended to become more and more eremitical and to run to great extravagances in the matter of bodily austerities. When Basil formed his monastery in the neighborhood of Neocaesarea in Pontus, he deliberately set himself against these tendencies. He declared that the cenobitical life is superior to the eremitical; that fasting and austerities should not interfere with prayer or work; that work should form an integral part of the monastic life, not merely as an occupation, but for its own sake and in order to do good to others; and therefore that monasteries should be near towns. Gregory of Nazianzus, who shared the retreat, aided Basil by his advice and experience. All this was a new departure in monachism.[2]

In his Rule, Basil follows a catechetical method; the disciple asks a question to which the master replies. As he visited early ascetic communities, the members would have questions. His responses were written down and formed the "Small Asketikon", published in 366.[3]

He limits himself to laying down indisputable principles which will guide the superiors and monks in their conduct. He sends his monks to the Sacred Scriptures; in his eyes the Bible is the basis of all monastic legislation, the true Rule. The questions refer generally to the virtues which the monks should practice and the vices they should avoid. The greater number of the replies contain a verse or several verses of the Bible accompanied by a comment which defines the meaning. The most striking qualities of the Basilian Rule are its prudence and its wisdom. It leaves to the superiors the care of settling the many details of local, individual, and daily life; it does not determine the material exercise of the observance or the administrative regulations of the monastery. Poverty, obedience, renunciation, and self-abnegation are the virtues which St. Basil makes the foundation of the monastic life.[1]

The Rule of Basil is divided into two parts: the "Greater Monastic Rules" and the "Lesser Rules". In 397, Rufinus who translated them into Latin united the two into a single Rule under the name of Regulae sancti Basilii episcopi Cappadociae ad monachos. Basil's influence ensured the propagation of Basilian monachism; and Sozomen says that in Cappadocia and the neighboring provinces there were no hermits but only cenobites. This Rule was followed by some Western monasteries, and was a major source for the Rule of St. Benedict.[3]

Monasteries

editThe monasteries of Cappadocia were the first to accept the Rule of St. Basil; it afterwards spread gradually to most of the monasteries of the East. Those of Armenia, Chaldea, and of the Syrian countries in general preferred instead those observances which were known among them as the Rule of St. Anthony. Protected by the emperors and patriarchs the monasteries increased rapidly in number. The monks took an active part in the ecclesiastical life of their time. Their monasteries were places of refuge for studious men. Many of the bishops and patriarchs were chosen from their ranks. They gave to the preaching of the Gospel its greatest apostles. The position of the monks in the empire was one of great power, and their wealth helped to increase their influence. Thus their development ran a course parallel to that of their Western brethren.[1]

The monks, as a rule, followed the theological vicissitudes of the emperors and patriarchs, and they showed no notable independence except during the iconoclastic persecution; the stand they took in this aroused the anger of the imperial controversialists. The Faith had its martyrs among them; many of them were condemned to exile, and some took advantage of this condemnation to reorganize their religious life in Italy.

Of all the monasteries of this period the most celebrated was that of St. John the Baptist of Stoudio, founded at Constantinople in the fifth century. It acquired its fame in the time of the iconoclastic persecution while it was under the government of the saintly hegoumenos (abbot) Theodore, called the Studite. In 781, Platon, a monk in the Symbola Monastery in Bithynia, and the uncle of Theodore the Studite, converted the family estate into the Sakkoudion Monastery. Platon served as abbot, with Theodore as his assistant. In 794, Theodore was ordained by Tarasios of Constantinople and became abbot. Around 797 Empress Irene made Theodore leader of the ancient Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople. He set himself to reform his monastery and restore St. Basil's spirit in its primitive vigour. But to effect this, and to give permanence to the reformation, he saw that there was need of a more practical code of laws to regulate the details of the daily life, as a supplement to St Basil's Rules. He therefore drew up constitutions, afterwards codified, which became the norm of the life at the Stoudios monastery, and gradually spread thence to the monasteries of the rest of the Greek empire. Thus to this day the Rules of Basil and the Constitutions of Theodore the Studite, along with the canons of the Councils, constitute the chief part of Greek and Russian monastic law.[2]

The monastery was an active center of intellectual and artistic life and a model which exercised considerable influence on monastic observances in the East. Theodore attributed the observances followed by his monks to his uncle, the saintly Abbot Plato, who first introduced them in his monastery of Sakkoudion. The other monasteries, one after another adopted them, and they are still followed by the monks of Mount Athos.

Monks from Athos participated at the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea of 787. In 885, a decree of Emperor Basil I proclaimed Mount Athos a place of monks, and no laymen or farmers or cattle-breeders are allowed to be settled there. The Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, built in 548, goes back to the early days of monasticism, and is still occupied by monks.[4]

Fine penmanship and the copying of manuscripts were held in honor among the Basilians. Among the monasteries which excelled in the art of copying were the Stoudios, Mount Athos, the monastery of the Isle of Patmos and that of Rossano in Sicily; the tradition was continued later by the monastery of Grottaferrata near Rome. These monasteries, and others as well, were studios of religious art where the monks toiled to produce miniatures in the manuscripts, paintings, and goldsmith work.

Notable monks

edit- Leontius of Byzantium (d. 543), author of an influential series of theological writings on sixth-century Christological controversies.[5]

- Sophronius of Jerusalem, Patriarch of Jerusalem in 634, a monk and theologian who was the chief protagonist for orthodox teaching in the doctrinal controversy on the essential nature of Jesus and his volitional acts.

- Maximus the Confessor, Abbot of Chrysopolis (d. 662), the most brilliant representative of Byzantine monasticism in the seventh century.[6]

- St. John Damascene, who wrote works expounding the Christian faith, and composed hymns which are still used both liturgically in Eastern Christian practice throughout the world as well as in western Lutheranism at Easter.[7]

The Byzantine monasteries furnish a long line of historians who were also monks: Georgius Syncellus, who wrote a "Selected Chronographia"; his friend and disciple Theophanes (d. 817), Abbot of the "Great Field" near Cyzicus, the author of another "Chronographia"; the Patriarch Nikephoros, who wrote (815–829) an historical "Breviarium" (a Byzantine history), and an "Abridged Chronographia";[8] George the Monk, whose Chronicle stops at A. D. 842.

There were, besides, a large number of monks, hagiographers, hymnologists, and poets who had a large share in the development of the Greek Liturgy. Among the authors of hymns may be mentioned: Romanus the Melodist;[9] Andrew of Crete; Cosmas of Jerusalem, and Joseph the Hymnographer.

From the beginning the Oriental Churches often took their patriarchs and bishops from the monasteries. Later, when the secular clergy was recruited largely from among married men, this custom became almost universal, for, as the episcopal office could not be conferred upon men who were married, it developed, in a way, into a privilege of the religious who had taken the vow of celibacy. Owing to this the monks formed a class apart, corresponding to the upper clergy of the Western Churches; this gave and still gives a preponderating influence to the monasteries themselves. In some of them theological instruction is given both to clerics and to laymen. In the East the convents for women adopted the Rule of St. Basil and had constitutions copied from those of the Basilian monks.

St. Cyril and St. Methodius, the Apostles of the Slavs were noted missionaries. In 1980, Pope John Paul II declared them co-patron saints of Europe, together with Benedict of Nursia.

During the Muslim conquest, a large number of monasteries were destroyed, especially those monasteries in Anatolia and the region around Constantinople.

Basilians in Italy

editAfter the Great Schism most Basilian monasteries became a part of the Eastern Orthodox Church; however, some Basilian monasteries which were in Italy remained in communion with the Western Church.

St. Nilus the Younger was a monk and a propagator of the rule of Saint Basil in Italy.[10] The Oratory of Saint Mark in Rossano, was founded by Nilus, as a place of retirement for nearby eremite monks. It retained the Greek Rite over the Latin Rite long after the town came under Norman rule. The Rossano Gospels is a 6th-century illuminated manuscript Gospel Book written following the reconquest of the Italian peninsula by the Byzantine Empire.

In 1004, Nilus founded the Basilian Monastery of Santa Maria, in Grottaferrata; it was completed by his disciple Bartholomew of Grottaferrata, who was also of Greek heritage.[11] The emigration of the Greeks to the West after the fall of Constantinople gave a certain prestige to these communities. Cardinal Bessarion, who was Abbot of Grottaferrata, sought to stimulate the intellectual life of the Basilians by means of the literary treasures which their libraries contained. Other Italian monasteries of the Basilian Order were affiliated with the monastery of Grottaferrata in 1561.

The Spanish Basilians were suppressed with the other orders in 1835 and have not been re-established.

Religious orders

edit- Order of Saint Basil the Great: a Ukrainian/Belarusian monastic religious order of the Greek Catholic Churches founded in 1631, and which has its Mother House in Rome at Santi Sergio e Bacco degli Ucraini.

- Ukrainian Studite Monks: ancient order absorbed into the Order of Saint Basil the Great in the 17th century, and reintroduced in 1919.

- Basilian Salvatorian Order of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church founded in 1683. The motherhouse is Monastery Saint Savior in Joun, Lebanon.

- Basilian Chouerite Order of Saint John the Baptist of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church founded in 1696. The motherhouse is the Church of Saint John the Baptist in Dhour El Choueir in Lebanon.

- Basilian Aleppian Order of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church founded in 1697. The headquarters of the order are located in Sarba, Jounieh, Lebanon.

- Basilian Chouerite Sisters of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church founded in 1737.

- Basilian Aleppian Sisters of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church founded in 1740.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Besse, Jean. "Rule of St. Basil." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 9 January 2020

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Basilian Monks". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 469.

- ^ a b Silvas, Anna M. The Rule of St. Basil in Latin and English: A Revised Critical Edition. Liturgical Press, 2013. ISBN 9780814682371

- ^ Din, Mursi Saad El et al.. Sinai: The Site & The History: Essays. New York: New York University Press, 1998. 80. ISBN 0814722032

- ^ "Leontius Byzantinus." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 10 January 2020

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Allen, Pauline; Neil, Bronwen (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Maximus the Confessor. Oxford University Press. p. 20.ISBN 978-0-19-967383-4

- ^ Lutheran Service Book (Concordia Publishing House, St. Louis, 2006), pp. 478, 487.

- ^ Alexander, Paul J., The Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople. Oxford University Press, 1958.

- ^ Phillimore, John. "St. Romanos." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 10 January 2020

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Fortescue, Adrian. "Nilus the Younger." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 7 November 2017

- ^ Exarchic Greek Abbey of St. Mary of Grottaferrata - Basilian Monks

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Rule of St. Basil". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.