Rose

| Rose Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Rosa rubiginosa, a wild rose native to Europe and West Asia | |

| |

| Rosa 'Precious Platinum', a hybrid tea garden cultivar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Subfamily: | Rosoideae |

| Tribe: | Roseae |

| Genus: | Rosa L.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Rosa cinnamomea L.[2]

| |

| Species | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus Rosa (/ˈroʊzə/),[4] in the family Rosaceae (/roʊˈzeɪsiːˌiː/),[4] or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars.[5] They form a group of plants that can be erect shrubs, climbing, or trailing, with stems that are often armed with sharp prickles.[6] Their flowers vary in size and shape and are usually large and showy, in colours ranging from white through yellows and reds. Most species are native to Asia, with smaller numbers native to Europe, North America, and Northwest Africa.[6] Species, cultivars and hybrids are all widely grown for their beauty and often are fragrant. Roses have acquired cultural significance in many societies. Rose plants range in size from compact, miniature roses to climbers that can reach seven meters in height.[6] Different species hybridize easily, and this has been used in the development of the wide range of garden roses.

Etymology

The name rose comes from Latin rosa, which was perhaps borrowed from Oscan, from Greek ῥόδον rhódon (Aeolic βρόδον wródon), itself borrowed from Old Persian wrd- (wurdi), related to Avestan varəδa, Sogdian ward, Parthian wâr.[7][8]

Botany

The leaves are borne alternately on the stem. In most species, they are 5 to 15 centimetres (2.0 to 5.9 in) long, pinnate, with (3–) 5–9 (−13) leaflets and basal stipules; the leaflets usually have a serrated margin, and often a few small prickles on the underside of the stem. Most roses are deciduous but a few (particularly from Southeast Asia) are evergreen or nearly so.

The flowers of most species have five petals, with the exception of Rosa omeiensis and Rosa sericea, which usually have only four. Each petal is divided into two distinct lobes and is usually white or pink, though in a few species yellow or red. Beneath the petals are five sepals (or in the case of some Rosa omeiensis and Rosa sericea, four). These may be long enough to be visible when viewed from above and appear as green points alternating with the rounded petals. There are multiple superior ovaries that develop into achenes.[9] Roses are insect-pollinated in nature.

The aggregate fruit of the rose is a berry-like structure called a rose hip. Many of the domestic cultivars do not produce hips, as the flowers are so tightly petalled that they do not provide access for pollination. The hips of most species are red, but a few (e.g. Rosa pimpinellifolia) have dark purple to black hips. Each hip comprises an outer fleshy layer, the hypanthium, which contains 5–160 "seeds" (technically dry single-seeded fruits called achenes) embedded in a matrix of fine, but stiff, hairs. Rose hips of some species, especially the dog rose (Rosa canina) and rugosa rose (R. rugosa), are very rich in vitamin C, among the richest sources of any plant. The hips are eaten by fruit-eating birds such as thrushes and waxwings, which then disperse the seeds in their droppings.

The sharp growths along a rose stem, though commonly called "thorns", are technically prickles, outgrowths of the epidermis (the outer layer of tissue of the stem), unlike true thorns, which are modified stems. Rose prickles are typically sickle-shaped hooks, which aid the rose in hanging onto other vegetation when growing over it. Some species such as Rosa rugosa and [R. pimpinellifolia have densely packed straight prickles, probably an adaptation to reduce browsing by animals, but also possibly an adaptation to trap wind-blown sand and so reduce erosion and protect their roots (both of these species grow naturally on coastal sand dunes). Despite the presence of prickles, roses are frequently browsed by deer. A few species of roses have only vestigial prickles that have no points.

Plant geneticist Zachary Lippman of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory found that prickles are controlled by the LOG gene.[10][11] Blocking the LOG gene in roses reduced the thorns (large prickles) into tiny buds.

Evolution

The oldest remains of roses are from the Late Eocene Florissant Formation of Colorado.[12] Roses were present in Europe by the early Oligocene.[13]

Today's garden roses come from 18th-century China.[14] Among the old Chinese garden roses, the Old Blush group is the most primitive, while newer groups are the most diverse.[15]

Genome

A study of the patterns of natural selection in the genome of roses indicated that genes related to DNA damage repair and stress adaptation have been positively selected, likely during their domestication.[16] This rapid evolution may reflect an adaptation to genome confliction resulting from frequent intra- and inter-species hybridization and switching environmental conditions of growth.[16]

Species

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

The genus Rosa is composed of 140–180 species and divided into four subgenera:[17]

- Hulthemia (formerly Simplicifoliae, meaning "with single leaves") containing two species from Southwest Asia, Rosa persica and Rosa berberifolia, which are the only roses without compound leaves or stipules.[18]

- Hesperrhodos (from the Greek for "western rose") contains Rosa minutifolia and Rosa stellata, from North America.

- Platyrhodon (from the Greek for "flaky rose", referring to flaky bark) with one species from east Asia, Rosa roxburghii (also known as the chestnut rose).

- Rosa (the type subgenus, sometimes incorrectly called Eurosa) containing all the other roses. This subgenus is subdivided into 11 sections.

- Banksianae – white and yellow flowered roses from China.

- Bracteatae – three species, two from China and one from India.

- Caninae – pink and white flowered species from Asia, Europe and North Africa.

- Carolinae – white, pink, and bright pink flowered species all from North America.

- Chinensis – white, pink, yellow, red and mixed-colour roses from China and Burma.

- Gallicanae – pink to crimson and striped flowered roses from western Asia and Europe.

- Gymnocarpae – one species in western North America (Rosa gymnocarpa), others in east Asia.

- Laevigatae – a single white flowered species from China.

- Pimpinellifoliae – white, pink, bright yellow, mauve and striped roses from Asia and Europe.

- Rosa (syn. sect. Cinnamomeae) – white, pink, lilac, mulberry and red roses from everywhere but North Africa.

- Synstylae – white, pink, and crimson flowered roses from all areas.

Ecology

Some birds, particularly finches, eat the seeds.

Pests and diseases

Wild roses are host plants for a number of pests and diseases. Many of these affect other plants, including other genera of the Rosaceae.

Cultivated roses are often subject to severe damage from insect, arachnid and fungal pests and diseases. In many cases they cannot be usefully grown without regular treatment to control these problems.

Uses

Roses are best known as ornamental plants grown for their flowers in the garden and sometimes indoors. They have also been used for commercial perfumery and commercial cut flower crops. Some are used as landscape plants, for hedging and for other utilitarian purposes such as game cover and slope stabilization.

Ornamental plants

The majority of ornamental roses are hybrids that were bred for their flowers. A few, mostly species roses are grown for attractive or scented foliage (such as Rosa glauca and R. rubiginosa), ornamental thorns (such as R. sericea) or for their showy fruit (such as R. moyesii).

Ornamental roses have been cultivated for millennia, with the earliest known cultivation known to date from at least 500 BC in Mediterranean countries, Persia, and China.[19] It is estimated that 30 to 35 thousand rose hybrids and cultivars have been bred and selected for garden use as flowering plants.[20] Most are double-flowered with many or all of the stamens having morphed into additional petals.

In the early 19th century the Empress Josephine of France patronized the development of rose breeding at her gardens at Malmaison. As long ago as 1840 a collection numbering over one thousand different cultivars, varieties and species was possible when a rosarium was planted by Loddiges nursery for Abney Park Cemetery, an early Victorian garden cemetery and arboretum in England.

Cut flowers

Roses are a popular crop for both domestic and commercial cut flowers. Generally they are harvested and cut when in bud, and held in refrigerated conditions until ready for display at their point of sale.

In temperate climates, cut roses are often grown in greenhouses, and in warmer countries they may also be grown under cover in order to ensure that the flowers are not damaged by weather and that pest and disease control can be carried out effectively. Significant quantities are grown in some tropical countries, and these are shipped by air to markets across the world.[21]

Some kind of roses are artificially coloured using dyed water, like rainbow roses.

Perfume

10H

18O)

Rose perfumes are made from rose oil (also called attar of roses), which is a mixture of volatile essential oils obtained by steam distilling the crushed petals of roses. An associated product is rose water which is used for cooking, cosmetics, medicine and religious practices. The production technique originated in Persia[22] and then spread through Arabia and India, and more recently into eastern Europe. In Bulgaria, Iran and Germany, damask roses (Rosa × damascena 'Trigintipetala') are used. In other parts of the world Rosa × centifolia is commonly used. The oil is transparent pale yellow or yellow-grey in colour. 'Rose Absolute' is solvent-extracted with hexane and produces a darker oil, dark yellow to orange in colour. The weight of oil extracted is about one three-thousandth to one six-thousandth of the weight of the flowers; for example, about two thousand flowers are required to produce one gram of oil.

The main constituents of attar of roses are the fragrant alcohols geraniol and L-citronellol and rose camphor, an odorless solid composed of alkanes, which separates from rose oil.[23] β-Damascenone is also a significant contributor to the scent.

Food and drink

Rose hips are high in vitamin C, are, after the removal of the irritant hairs, edible raw,[24] and occasionally are made into jam, jelly, marmalade, and soup, or brewed for tea. They are also pressed and filtered to make rose hip syrup. Rose hips are also used to produce rose hip seed oil, which is used in skin products and some makeup products.[25]

Rose water has a very distinctive flavour and is used in Middle Eastern, Persian, and South Asian cuisine—especially in sweets such as Turkish delight,[26] barfi, baklava, halva, gulab jamun, knafeh, and nougat. Rose petals or flower buds are sometimes used to flavour ordinary tea, or combined with other herbs to make herbal teas. A sweet preserve of rose petals called gulkand is common in the Indian subcontinent. The leaves and washed roots are also sometimes used to make tea.[24]

In France, there is much use of rose syrup, most commonly made from an extract of rose petals. In the Indian subcontinent, Rooh Afza, a concentrated squash made with roses, is popular, as are rose-flavoured frozen desserts such as ice cream and kulfi.[27][28]

The flower stems and young shoots are edible, as are the petals (sans the white or green bases).[24] The latter are usually used as flavouring or to add their scent to food.[29] Other minor uses include candied rose petals.[30]

Rose creams (rose-flavoured fondant covered in chocolate, often topped with a crystallised rose petal) are a traditional English confectionery widely available from numerous producers in the UK.

Under the American Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act,[31] there are only certain Rosa species, varieties, and parts are listed as generally recognized as safe (GRAS).

- Rose absolute: Rosa alba L., Rosa centifolia L., Rosa damascena Mill., Rosa gallica L., and vars. of these spp.

- Rose (otto of roses, attar of roses): Ditto

- Rose buds

- Rose flowers

- Rose fruit (hips)

- Rose leaves: Rosa spp.[32]

As a food ingredient

The rose hip, usually from R. canina, is used as a minor source of vitamin C.[33] Diarrhodon (Gr διάρροδον, "compound of roses", from ῥόδων, "of roses"[34]) is a name given to various compounds in which red roses are an ingredient.

Art and symbolism

The long cultural history of the rose has led to it being used often as a symbol. In ancient Greece, the rose was closely associated with the goddess Aphrodite.[35][36] In the Iliad, Aphrodite protects the body of Hector using the "immortal oil of the rose"[37][35] and the archaic Greek lyric poet Ibycus praises a beautiful youth saying that Aphrodite nursed him "among rose blossoms".[38][35] The second-century AD Greek travel writer Pausanias associates the rose with the story of Adonis and states that the rose is red because Aphrodite wounded herself on one of its thorns and stained the flower red with her blood.[39][35] Book Eleven of the ancient Roman novel The Golden Ass by Apuleius contains a scene in which the goddess Isis, who is identified with Venus, instructs the main character, Lucius, who has been transformed into a donkey, to eat rose petals from a crown of roses worn by a priest as part of a religious procession in order to regain his humanity.[36] French writer René Rapin invented a myth in which a beautiful Corinthian queen named Rhodanthe ("she with rose flowers") was besieged inside a temple of Artemis by three ardent suitors who wished to worship her as a goddess; the god Apollo then transformed her into a rosebush.[40]

Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire, the rose became identified with the Virgin Mary. The colour of the rose and the number of roses received has symbolic representation.[41][42][36] The rose symbol eventually led to the creation of the rosary and other devotional prayers in Christianity.[43][36]

Ever since the 1400s, the Franciscans have had a Crown Rosary of the Seven Joys of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[36] In the 1400s and 1500s, the Carthusians promoted the idea of sacred mysteries associated with the rose symbol and rose gardens.[36] Albrecht Dürer's painting The Feast of the Rosary (1506) depicts the Virgin Mary distributing garlands of roses to her devotees.[36]

Roses symbolised the Houses of York and Lancaster in a conflict known as the Wars of the Roses. Subsequently roses of the corresponding colours have been used a emblems for the English counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire.

The Tudor rose combines the colours of the roses of York and Lancaster, and is an emblem of then Tudor dynasty and of England.

Roses are a favored subject in art and appear in portraits, illustrations, on stamps, as ornaments or as architectural elements. The Luxembourg-born Belgian artist and botanist Pierre-Joseph Redouté is known for his detailed watercolours of flowers, particularly roses.

Henri Fantin-Latour was also a prolific painter of still life, particularly flowers including roses. The rose 'Fantin-Latour' was named after the artist.

Other impressionists including Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir have paintings of roses among their works. In the 19th century, for example, artists associated the city of Trieste with a certain rare white rose, and this rose developed as the city's symbol. It was not until 2021 that the rose, which was believed to be extinct, was rediscovered there.[44]

In 1986 President Ronald Reagan signed legislation to make the rose[45] the floral emblem of the United States.[46]

The rose is often exchanged on St. Valentines Day and is used often as a symbol of such.[47]

-

Codex Manesse illuminated with roses, illustrated between 1305 and 1340 in Zürich. It contains love songs in Middle High German

-

Princess Maria Amélia of Brazil with a rose in her hair (1849)

-

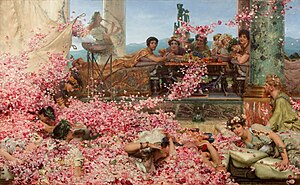

The Roses of Heliogabalus by Alma-Tadema (1888)

-

White rose pictured in the coat of arms of Viljandi

-

Insignia of the Brazilian Order of the Rose

See also

- ADR rose

- List of Award of Garden Merit roses

- List of rose cultivars named after people

- Rose (colour)

- Rose garden

- Rose Hall of Fame

- Rose show

- Rose trial grounds

References

- ^ "Rosa". International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ "Rosa". International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ "Rosa L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ a b Gove, Philip B., ed. (1961). Webster's Third New International Dictionary. G. & C. Merriam.

- ^ "Roses - Rosa | Plants | Kew". www.kew.org. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ a b c "Rose | Description, Species, Images, & Facts". Britannica. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ^ The Free Dictionary, "rose".

- ^ "GOL". Encyclopaedia Iranica. February 9, 2012 [December 15, 2001]. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Mabberley, D. J. (1997). The Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of the Vascular Plants. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41421-0.

- ^ Satterlee, J.W.; Alonso, D.; Gramazio, P. (2024). "Convergent evolution of plant prickles by repeated gene co-option over deep time". Science. 385 (6708): 1663. doi:10.1126/science.ado1663. PMC 11305333. PMID 39088611.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (August 1, 2024). "How Did Roses Get Their Thorns?". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ DeVore, M. L.; Pigg, K. B. (July 2007). "A brief review of the fossil history of the family Rosaceae with a focus on the Eocene Okanogan Highlands of eastern Washington State, USA, and British Columbia, Canada". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 266 (1–2): 45–57. Bibcode:2007PSyEv.266...45D. doi:10.1007/s00606-007-0540-3. ISSN 0378-2697. S2CID 10169419.

- ^ Kellner, A.; Benner, M.; Walther, H.; Kunzmann, L.; Wissemann, V.; Ritz, C. M. (March 2012). "Leaf Architecture of Extant Species of Rosa L. and the Paleogene Species Rosa lignitum Heer (Rosaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 173 (3): 239–250. doi:10.1086/663965. ISSN 1058-5893. S2CID 83909271.

- ^ "The History of Roses — Our Rose Garden". University of Illinois Extension. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ Tan, Jiongrui; Wang, Jing; Luo, Le; Yu, Chao; Xu, Tingliang; Wu, Yuying; Cheng, Tangren; Wang, Jia; Pan, Huitang; Zhang, Qixiang (2017). "Genetic relationships and evolution of old Chinese garden roses based on SSRs and chromosome diversity – Scientific Reports". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 15437. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15815-6. PMC 5684293. PMID 29133839.

- ^ a b Li S, Zhong M, Dong X, Jiang X, Xu Y, Sun Y, Cheng F, Li DZ, Tang K, Wang S, Dai S, Hu JY (December 2018). "Comparative transcriptomics identifies patterns of selection in roses". BMC Plant Biol. 18 (1): 371. doi:10.1186/s12870-018-1585-x. PMC 6303930. PMID 30579326.

- ^ Leus, Leen; Van Laere, Katrijn; De Riek, Jan; Van Huylenbroeck, Johan (2018). "Rose". In Van Huylenbroeck, Johan (ed.). Ornamental Crops. Handbook of Plant Breeding. Vol. 11. Springer. pp. 719–767 See p. 720. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90698-0_27. ISBN 978-3-319-90697-3.

- ^ "Rosa persica - Trees and Shrubs Online". www.treesandshrubsonline.org. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

- ^ Goody, Jack (1993). The Culture of Flowers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41441-5. OCLC 1148849511.

- ^ Bendahmane, Mohammed; Dubois, Annick; Raymond, Olivier; Bris, Manuel Le (2013). "Genetics and genomics of flower initiation and development in roses". Journal of Experimental Botany. 64 (4): 847–857. doi:10.1093/jxb/ers387. PMC 3594942. PMID 23364936.

- ^ "ADC Commercialisation bulletin #4: Fresh cut roses" (PDF). FOODNET Uganda 2009. May 14, 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Nikbakht, Ali; Kafi, M.A. (January 2004). "A study on the relationships between Iranian people and Damask rose (Rosa damascena) and its therapeutic and healing properties". Acta Horticulturae. 790: 251–4. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2008.790.36.

The origin of Damask rose is the Middle East and it is the national flower of Iran. Rose oil usage dates back to ancient civilization of Persia. Avicenna, the 10th century Persian physician, distilled its petals for medical purposes and commercial distillery existed in 1612 in Shiraz, Persia.

- ^ Stewart, D. (2005). The Chemistry Of Essential Oils Made Simple: God's Love Manifest In Molecules. Care. ISBN 978-0-934426-99-2.

- ^ a b c Angier, Bradford (1974). Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 186. ISBN 0-8117-0616-8. OCLC 799792.

- ^ "Rose Hip Benefits". Herbwisdom.com. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Rosewater recipes – BBC Food". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ "Rose Flavored Ice Cream with Rose Petals". eCurry.

- ^ Samanth Subramanian (27 April 2012). "Rooh Afza, the syrup that sweetens the subcontinent's summers". The National.

- ^ "St. Petersburg Times – Google News Archive Search". google.com.

- ^ "rosepetal candy – Google Search". google.co.uk.

- ^ "Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS)". Food and Drug Administration. 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR)". Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR).

- ^ "Rosa chinensis China Rose PFAF Plant Database". Pfaf.org. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "dia-". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c d Cyrino, Monica S. (2010). Aphrodite. Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World. Routledge. pp. 63, 96. ISBN 978-0-415-77523-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clark, Nora (2015). Aphrodite and Venus in Myth and Mimesis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1-4438-7127-3.

- ^ Iliad 23.185–187

- ^ Ibycus, fragment 288.4

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 6.24.7 Archived 2018-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Watts, Donald C. (May 2, 2007). Dictionary of Plant Lore. Bath, United Kingdom: Elsevier. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-12-374086-1.

- ^ "Rose Flower Meaning and Symbolism". 20 July 2016.

- ^ Cucciniello, Lisa (2008). "Rose to Rosary: The Flower of Venus in Catholicism". In Hutton, Frankie (ed.). Rose Lore: Essays in Semiotics and Cultural History. Lexington Books. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-7391-3015-5. OCLC 248733215.

- ^ Cucciniello 2008, pp. 65–67

- ^ Ugo Salvini "La rarissima Rosa di Trieste spezza l’oblio e rispunta a sorpresa sulle colline di Muggia" In: Il Piccolo 27.01.2021, La Rosa.

- ^ "National Flower | The Rose". statesymbolsusa.org. 6 May 2014.

- ^ "National Flower of United States – Fresh from the Grower". Growerflowers.com. Retrieved 2021-02-26.

- ^ "Giving Roses for Valentine's Day? Here's How the Flower Came to Symbolize Love". TIME. 2019-02-13. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

External links

- World Federation of Rose Societies

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.