Saint Kitts and Nevis

Federation of Saint Christopher and Nevis | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Country Above Self" | |

| Anthem: "O Land of Beauty!" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Basseterre 17°18′N 62°44′W / 17.300°N 62.733°W |

| Official languages | English |

| Vernacular language | Saint Kitts Creole |

| Ethnic groups (2020)[1] |

|

| Religion (2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Marcella Liburd | |

| Terrance Drew | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 27 February 1967 | |

• Independence declared | 19 September 1983 |

| Area | |

• Total | 261 km2 (101 sq mi) (188th) |

• Water (%) | Negligible |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 47,606[3][4] (187th) |

• 2023 census | 54,338 |

• Density | 164/km2 (424.8/sq mi) (64th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | very high (51st) |

| Currency | East Caribbean dollar (EC$) (XCD) |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +1 869 |

| ISO 3166 code | KN |

| Internet TLD | .kn |

| |

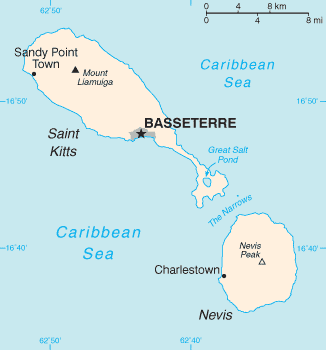

Saint Kitts and Nevis (/-ˈkɪts ... ˈniːvɪs/ ), officially the Federation of Saint Christopher and Nevis,[7] is an island country consisting of the two islands of Saint Kitts and Nevis, both located in the West Indies, in the Leeward Islands chain of the Lesser Antilles. With 261 square kilometres (101 sq mi) of territory, and roughly 48,000 inhabitants, it is the smallest sovereign state in the Western Hemisphere, in both area and population, as well as the world's smallest sovereign federation.[1] The country is a Commonwealth realm, with Charles III as King and head of state.[1][8]

The capital city is Basseterre, located on the larger island of Saint Kitts.[1] Basseterre is also the main port for passenger entry (via cruise ships) and cargo. The smaller island of Nevis lies approximately 3 km (2 mi) to the southeast of Saint Kitts, across a shallow channel called The Narrows.[1]

The British dependency of Anguilla was historically also a part of this union, which was known collectively as Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla. However, Anguilla chose to secede from the union in 1967, and remains a British overseas territory.[1]

Saint Kitts and Nevis were among the first islands in the Caribbean to be colonised by Europeans. Saint Kitts was home to the first British and French Caribbean colonies, and thus has also been titled "The Mother Colony of the West Indies".[9] It is also the most recent British territory in the Caribbean to become independent, gaining independence in 1983.

Etymology

[edit]

The Kalinago, the pre-European inhabitants of Saint Kitts, called the island Liamuiga, roughly translating as 'fertile land'.[10]

It is thought that Christopher Columbus, the first European to see the islands in 1493, named the larger island San Cristóbal, after Saint Christopher, his patron saint and that of travellers. New studies suggest that Columbus named the island Sant Yago (Saint James), and that the name San Cristóbal was in fact given by Columbus to the island now known as Saba, 32 km (20 mi) northwest. Saint Kitts was well documented as San Cristóbal by the 17th century.[1] The first English colonists kept the English translation of this name, and dubbed it St. Christopher's Island. In the 17th century, a common nickname for Christopher was Kit(t); hence, the island came to be informally referred to as Saint Kitt's Island, later further shortened to Saint Kitts.[1]

Columbus gave Nevis the name San Martín (Saint Martin).[10] The current name Nevis is derived from a Spanish name Nuestra Señora de las Nieves, meaning "Our Lady of the Snows", a reference to the 4th-century Catholic miracle of a summertime snowfall on the Esquiline Hill in Rome.[1] It is not known who chose this name for the island, but it is thought that white clouds which usually wreath the top of Nevis Peak reminded someone of the miracle.[11][1]

Today, the Constitution refers to the state as both Saint Kitts and Nevis and Saint Christopher and Nevis; the former is the one most commonly used, but the latter is generally used for diplomatic relations. Passports list the nationality of citizens as St. Kitts and Nevis.[12]

History

[edit]

Pre-colonial period

[edit]The name of the first inhabitants, pre-Arawakan peoples who settled the islands perhaps as early as 3,000 years ago, is not known.[13] They were followed by the Arawak peoples, or Taíno, around 1000 BC.[citation needed] The Island Caribs invaded around 800 AD.[14]: 10

European arrival and early colonial period, 1493–1700

[edit]Christopher Columbus was the first European to sight the islands in 1493.[15][8] The first settlers were the English in 1623, led by Thomas Warner, who established a settlement at Old Road Town on the west coast of St Kitts after achieving an agreement with the Carib chief Ouboutou Tegremante.[14]: 15–18 [8] The French later also settled on St Kitts in 1625 under Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc.[8] As a result, both parties agreed to partition the island into French and English sectors. From 1628 onward the English also began settling on Nevis.[8]

The French and English, intent on exploitation of the island's resources,[16] encountered resistance from the native Caribs (Kalinago), who waged war during the first three years of the settlements' existence.[17][18] The Europeans resolved to rid themselves of this problem. An ideological campaign was waged by colonial chroniclers, dating back to the Spanish, as they produced literature which denied the Kalinagos' humanity (a literary tradition carried through the late-seventeenth century by such authors as Jean-Baptiste du Tertre and Pere Labat).[18] In 1626 the Anglo-French settlers joined forces to massacre the Kalinago at a place that became known as Bloody Point, allegedly to preempt a Carib plan to expel or kill all European settlers.[19][20] Thereafter, the English and French established large sugar plantations which were worked by imported African slaves. This made the planter-colonists rich, but drastically altered the islands' demographics as black slaves soon came to outnumber Europeans.[15][14]: 26–31

A Spanish expedition of 1629 sent to enforce Spanish claims destroyed the English and French colonies and deported the settlers back to their respective countries. As part of the war settlement in 1630, the Spanish permitted the re-establishment of the English and French colonies.[14]: 19–23 Spain later formally recognised Britain's claim to St Kitts with the Treaty of Madrid (1670), in return for British cooperation in the fight against piracy.[21]

As Spanish power declined, Saint Kitts became a key base for English and French expansion in the Caribbean. From St Kitts the British settled the islands of Antigua, Montserrat, Anguilla and Tortola, and the French settled Martinique, the Guadeloupe archipelago and Saint Barthélemy. During the late 17th century, France and England fought for control over St Kitts and Nevis, fighting wars in 1667,[14]: 41–50 1689–90[14]: 51–55 and 1701–13. The French renounced their claim to the islands with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.[14]: 55–60 [8] The islands' economy, already shattered by war, was further harmed by natural disasters: In 1690 an earthquake destroyed Jamestown, capital of Nevis, forcing the construction of a new capital at Charlestown. Further damage was caused by a hurricane in 1707.[22]: 105–108

British colonial period 1700–1983

[edit]The colony had recovered by the turn of the 18th century, and St Kitts had become the richest British Crown Colony per capita in the Caribbean as result of its slave-based sugar industry by the close of the 1700s.[23] The 18th century also saw Nevis, formerly the richer of the two islands, being eclipsed by St Kitts in economic importance.[14]: 75 [22]: 126, 137 Alexander Hamilton, the future U.S. secretary of the Treasury, was born on Nevis in 1755 or 1757.[24]

As Britain became embroiled in war with its American colonies, the French decided to use the opportunity to re-capture St Kitts in 1782; however St Kitts was given back and recognised as British territory in the Treaty of Versailles (1783).[8][15]

The African slave trade was terminated within the British Empire in 1807, and slavery outlawed completely in 1834. A four-year "apprenticeship" period followed for each slave, in which they worked for their former owners for wages. On Nevis 8,815 slaves were freed, while St Kitts freed 19,780.[22]: 174 [14]: 110, 114–117

Saint Kitts and Nevis, along with Anguilla, were federated in 1882. In the first few decades of the 20th century economic hardship and lack of opportunities led to the growth of a labour movement; the Great Depression prompted sugar workers to go on strike in 1935.[25] The 1940s saw the founding of the St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla Labour Party (later renamed the Saint Kitts and Nevis Labour Party, or SKNLP)[26] under Robert Llewellyn Bradshaw. Bradshaw later became Chief Minister and then Premier of the colony from 1966 to 1978; he sought to gradually bring the sugar-based economy under greater state control.[14]: 151–152 The more conservative-leaning People's Action Movement party (PAM) was founded in 1965.[27]

After a brief period as part of the West Indies Federation (1958–62), the islands became an associated state with full internal autonomy in 1967.[8] Residents of Nevis and Anguilla were unhappy with St Kitts's domination of the federation, and Anguilla unilaterally declared independence in 1967.[15][8] In 1971 Britain resumed full control of Anguilla, but it was formally separated in 1980.[28][14]: 147–149 [8] Attention then focused on Nevis, with the Nevis Reformation Party seeking to safeguard the smaller island's interests in any future independent state. Eventually it was agreed that the island would have a degree of autonomy with its own Premier and Assembly, as well as the constitutionally-protected right to unilaterally secede if a referendum on independence resulted in a two-thirds majority in favour.[29][30]

Post independence era, 1983–present

[edit]

St Kitts and Nevis achieved full independence on 19 September 1983.[8][15] Kennedy Simmonds of the PAM, Premier since 1980, duly became the country's first Prime Minister. St Kitts and Nevis opted to remain within the British Commonwealth, at that time retaining Queen Elizabeth as Monarch, represented locally by a Governor-General.[citation needed] Kennedy Simmonds went on to win elections in 1984, 1989 and 1993, before being unseated when the SKNLP returned to power in 1995 under Denzil Douglas.[15][8]

In Nevis, growing discontent with their perceived marginalisation within the federation[31] led to a referendum to separate from St Kitts in 1998, which though resulting a 62% vote to secede, fell short of the required two-thirds majority to be legally enacted.[32][15][8]

In late-September 1998, Hurricane Georges caused approximately $458,000,000 in damages and limited GDP growth for the year and beyond. Meanwhile, the sugar industry, in decline for years and propped up only by government subsidies, was closed completely in 2005.[8][33]

In 2012, Saint Kitts and Nevis was declared free of malaria, according to the World Health Organization.

The 2015 Saint Kitts and Nevis general election was won by Timothy Harris and his recently formed People's Labour Party, with backing from the PAM and the Nevis-based Concerned Citizens' Movement under the 'Team Unity' banner.[34]

In June 2020, Team Unity coalition of the incumbent government, led by Prime Minister Timothy Harris, won general elections by defeating Saint Kitts and Nevis Labour Party (SKNLP).[35]

In snap general elections held in August 2022, the SKNLP again won, and Terrance Drew became the fourth prime minister of Saint Kitts and Nevis.[36]

Politics

[edit]

Saint Kitts and Nevis is a sovereign, democratic, and federal state.[37] It is a Commonwealth realm,[38] a constitutional monarchy with the King of Saint Christopher and Nevis, Charles III, as its head of state.[1] The King is represented in the country by a Governor-General, who acts on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet. The Prime Minister is the leader of the majority party of the House, and the cabinet conducts affairs of state.[citation needed]

St. Kitts and Nevis has a unicameral legislature, known as the National Assembly. It is composed of fourteen members: eleven elected representatives (three from the island of Nevis) and three senators, who are appointed by the Governor-General.[1] Two of the senators are appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister, and one, on the advice of the leader of the opposition. Unlike in other countries, the senators do not constitute a separate senate or upper house of parliament, but sit in the National Assembly alongside representatives. All members serve five-year terms. The Prime Minister and the Cabinet answer to the Parliament. Nevis also maintains its own semi-autonomous assembly.[citation needed]

Foreign relations

[edit]Saint Kitts and Nevis has no major international disputes. Saint Kitts and Nevis is a full and participating member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), and the Organisation of American States (OAS).[1]

St Kitts & Nevis entered the OAS system on 16 September 1984.[39]

Agreements which impact on financial relationships

[edit]

Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaty 1994

[edit]At a CARICOM meeting, representative of St. Kitts and Nevis Kennedy Simmons signed the Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaty 1994, on 6 July 1994.[40]

The representatives of seven CARICOM countries signed similar agreements at Sherbourne Conference Centre, St. Michael, Barbados.[40] The countries whose representatives signed the treaties in Barbados were: Antigua & Barbuda, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines and Trinidad and Tobago.[40] This treaty covered income, residence, tax jurisdictions, capital gains, business profits, interest, dividends, royalties and other areas.[citation needed]

FATCA

[edit]On 30 June 2014, St. Kitts and Nevis signed a Model 1 agreement with the United States of America in relation to Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA).[41]

Military

[edit]Saint Kitts and Nevis has a defence force of 300 personnel. It is mostly involved in policing and drug trade interception.[citation needed]

Human rights

[edit]Male homosexuality has been legal in St. Kitts and Nevis since 29 August 2022.[42] In 2011, the Government of St. Kitts and Nevis said it had "no mandate from the people" to abolish the criminalisation of homosexuality among consenting adults.[43]

Administrative divisions

[edit]The federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis is divided into fourteen parishes, nine of them on Saint Kitts and five on Nevis.[citation needed]

|

| Parishes | Capital | Population 2011 |

Area (km2) |

Population density per km2 |

Island |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christ Church Nichola Town | Nichola Town | 1,922 | 18 | 107 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint Anne Sandy Point | Sandy Point Town | 2,626 | 13 | 202 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint George Basseterre | Basseterre | 12,635 | 29 | 436 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint John Capisterre | Dieppe Bay Town | 2,962 | 25 | 118 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint Mary Cayon | Cayon | 3,435 | 15 | 229 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint Paul Capisterre | Saint Paul Capisterre | 2,432 | 14 | 174 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint Peter Basseterre | Monkey Hill | 4,670 | 21 | 222 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint Thomas Middle Island | Middle Island | 2,535 | 25 | 101.4 | Saint Kitts |

| Trinity Palmetto Point | Trinity | 1,701 | 16 | 106 | Saint Kitts |

| Saint George Gingerland | Market Shop | 2,496 | 18 | 139 | Nevis |

| Saint James Windward | Newcastle | 2,038 | 32 | 64 | Nevis |

| Saint John Figtree | Figtree | 3,827 | 22 | 174 | Nevis |

| Saint Paul Charlestown | Charlestown | 1,847 | 4 | 462 | Nevis |

| Saint Thomas Lowland | Cotton Ground | 2,069 | 18 | 115 | Nevis |

Geography

[edit]

The capital city is Basseterre, located on the larger island of Saint Kitts.[1] Basseterre is also the main port for passenger entry (via cruise ships) and cargo. The smaller island of Nevis lies approximately 3 km (2 mi) to the southeast of Saint Kitts, across a shallow channel called The Narrows.[1] The islands of Sint Eustatius, Saba, Saint Barthélemy, Saint-Martin/Sint Maarten and Anguilla lie to the north-northwest of the country. To the east and northeast are Antigua and Barbuda, and to the southeast is the small uninhabited island of Redonda (part of Antigua and Barbuda) and the island of Montserrat.

The country consists of two main islands, Saint Kitts and Nevis, separated at a distance of 2 miles (3 km) by The Narrows strait.[8] Both are of volcanic origin, with large central peaks covered in tropical rainforest.[1] The majority of the population live along the flatter coastal areas.[1] St Kitts contains several mountain ranges (the North West Range, Central Range and South-West Range) in its centre, where the highest peak of the country, Mount Liamuiga 1,156 metres (3,793 ft) can be found.[8] Along the east coast can be found the Canada Hills and Conaree Hills. The land narrows considerably in the south-east, forming a much flatter peninsula which contains the largest body of water, the Great Salt Pond. To the southeast, in The Narrows, lies the small isle of Booby Island. There are numerous rivers descending from the mountains of both islands, which provide fresh water to the local population. Nevis, the smaller of the two main islands and roughly circular in shape, is dominated by Nevis Peak 985 metres (3,232 ft).[1]

Saint Kitts and Nevis contains two terrestrial ecoregions: Leeward Islands moist forests and Leeward Islands dry forests.[44] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.55/10, ranking it 121st globally out of 172 countries.[45]

Fauna

[edit]The national bird is the brown pelican.[46] 176 species of bird have been reported from the country.[47]

Flora

[edit]The national flower is Delonix regia. Common plants include palmetto, hibiscus, bougainvillea, and tamarind. Pinus species are common in the dense forests of islands, and are usually covered by various species of ferns.[48]

Climate

[edit]By the Köppen climate classification, St Kitts has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw) and Nevis has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am).[49] Mean monthly temperatures in Basseterre varies little from 23.9 °C (75.0 °F) to 26.6 °C (79.9 °F). Yearly rainfall is approximately 2,400 millimetres (90 in), although it has varied from 1,356 millimetres (53.4 in) to 3,183 millimetres (125.3 in) in the period 1901–2015.[50]

| Climate data for Saint Kitts and Nevis (1991–2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 150 (5.9) |

102 (4.0) |

99 (3.9) |

153 (6.0) |

219 (8.6) |

181 (7.1) |

214 (8.4) |

232 (9.1) |

222 (8.7) |

289 (11.4) |

286 (11.3) |

225 (8.9) |

2,372 (93.3) |

| Source: Climate Change Knowledge Portal[50] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

Population

[edit]The population of Saint Kitts and Nevis is around 53,000 (July 2019 est.)[1] and has remained relatively constant for many years.[8] At the end of the nineteenth century there were 42,600 residents, the number slowly rising to a little over 50,000 by the mid-twentieth century.[51] Between 1960 and 1990, the population dropped from 50,000 to 40,000, before rising again to its current level. Approximately three-quarters of the population live on Saint Kitts, with 15,500 of these living in the capital, Basseterre. Other large settlements include Cayon (population 3,000) and Sandy Point Town (3,000), both on Saint Kitts, and Gingerland (2,500) and Charlestown (1,900), both on Nevis.[citation needed] It ranks number 209 on the list of countries and dependencies by population.[52]

Racial and ethnic groups

[edit]The population is primarily Afro-Caribbean (92.5%), with significant minorities of European (2.1%) and Indian (1.5%) descent (2001 estimate).[1]

Emigration

[edit]As of 2021[update], there were 47,606 inhabitants; their average life expectancy is 76.9 years. Emigration has historically been very high, so high that the total estimated population in 2007 was little changed from that in 1961.[53]

Emigration from St Kitts and Nevis to the United States:[46]

- 1986–1990: 3,513

- 1991–1995: 2,730

- 1996–2000: 2,101

- 2001–2005: 1,756

- 2006–2010: 1,817

Languages

[edit]English is the sole official language. Saint Kitts Creole is also widely spoken.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Most inhabitants (82%) are Christians, most of whom belong to Anglican, Methodist, and other Protestant denominations.[1] Roman Catholics are pastorally served by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Saint John's–Basseterre, and Anglicans by the Diocese of the North East Caribbean and Aruba.[citation needed]

Hinduism is the largest non-Christian religion, followed by 1.82% of the population;[54] these are primarily Indo-Kittitians and Indo-Nevisians.[citation needed]

According to the 2011 census, 17 per cent of the population is Anglican, 16 per cent Methodist, 11 per cent Pentecostal, 7 per cent Church of God, 6 per cent Roman Catholic, 5 per cent each Baptist, Moravian, Seventh-day Adventist, and Wesleyan Holiness, 4 per cent "Other", and 2 per cent each Brethren, evangelical Christian, and Hindu.[56]

Culture

[edit]Music and festivals

[edit]

Saint Kitts and Nevis is known for a number of musical celebrations including Carnival (18 December to 3 January on Saint Kitts). The last week in June features the St Kitts Music Festival, while the week-long Culturama on Nevis lasts from the end of July into early August.[57]

Additional festivals on the island of Saint Kitts include Inner City Fest, in February in Molineaux; Green Valley Festival, usually around Whit Monday in village of Cayon; Easterama, around Easter in village of Sandy Point; Fest-Tab, in July or August in the village of Tabernacle; and La festival de Capisterre, around Independence Day in Saint Kitts and Nevis (19 September), in the Capisterre region. These celebrations typically feature parades, street dances and salsa, jazz, soca, calypso and steelpan music.[citation needed]

The 1985 film Missing in Action 2: The Beginning was filmed in Saint Kitts.[58]

Media

[edit]Sports

[edit]Cricket is common in Saint Kitts and Nevis. Top players can be selected for the West Indies cricket team. The late Runako Morton was from Nevis. Saint Kitts and Nevis was the smallest country to host 2007 Cricket World Cup matches,[59] which were played at the Warner Park Stadium.[60]

Rugby and netball are also common in Saint Kitts and Nevis as well.[citation needed]

The St Kitts and Nevis national football team, also known as the "Sugar Boyz", has experienced some international success in recent years, progressing to the semi-final round of qualification for the 2006 FIFA World Cup in the CONCACAF region. Led by Glence Glasgow, they defeated the US Virgin Islands and Barbados before they were outmatched by Mexico, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. Atiba Harris is the first footballer from the country to play in Major League Soccer and arguably the most famous footballer from the country. He is the current President of the SKNFA. Despite not representing the country, Marcus Rashford is of descent,[61] as is Cole Palmer.[62]

The national team achieved its greatest success of the modern era when it qualified for the 2023 CONCACAF Gold Cup defeating the Curaçao national football team and the French Guiana national football team in a penalty shootout in the preliminary round. It was drawn into Group A with Jamaica, the United States, and Trinidad & Tobago, but lost all three games.[63]

The St Kitts and Nevis Billiard Federation, SKNBF, is the governing body for cue sports across the two islands. The SKNBF is a member of the Caribbean Billiards Union (CBU) with the SKNBF President Ste Williams holding the post of CBU Vice-president.[citation needed]

Kim Collins is the country's foremost track and field athlete. He has won gold medals in the 100 metres at both the World Championships in Athletics and Commonwealth Games, and at the 2000 Sydney Olympics he was the country's first athlete to reach an Olympic final. He and three other athletes represented St Kitts and Nevis at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. The four by one hundred metre relay team won a bronze medal at the 2011 world championships.[64] Jason Rogers, Antoine Adams, and Brijesh Lawrence ran the other three relay legs with Collins.[citation needed]

American writer and former figure skater and triathlete Kathryn Bertine was granted dual citizenship in an attempt to make the 2008 Summer Olympics representing St Kitts and Nevis in women's cycling. Her story was chronicled online at ESPN.com as a part of its E-Ticket feature entitled "So You Wanna Be An Olympian?" She ultimately failed to earn the necessary points for Olympic qualification.[65]

St Kitts and Nevis had two athletes ride in the time trial at the 2010 UCI Road World Championships: Reginald Douglas and James Weekes.[66]

Economy

[edit]

Saint Kitts and Nevis is a twin-island federation whose economy is characterised by its dominant tourism, agriculture, and light manufacturing industries.[1] Sugar was the primary export from the 1940s on, but rising production costs, low world market prices, and the government's efforts to reduce dependence on it have led to a growing diversification of the agricultural sector. In 2005, the government decided to close down the state-owned sugar company, which had experienced losses and was a significant contributor to the fiscal deficit.[8][1]

St Kitts and Nevis is heavily dependent upon tourism to drive its economy, a sector which has expanded significantly since the 1970s.[1][8] In 2009 there were 587,479 arrivals to Saint Kitts compared to 379,473 in 2007, an increase of just under 40% in a two-year period; however, the tourist sector declined during the Great Recession and then rebounded slowly.[1] In the 21st century, the government has sought to diversify the economy via agriculture, tourism, export-oriented manufacturing, and offshore banking.[1]

In July 2015, St Kitts & Nevis and the Republic of Ireland signed a tax agreement to "promote international co-operation in tax matters through exchange of information." The agreement was developed by the OECD Global Forum Working Group on Effective Exchange of Information, which consisted of representatives from OECD member countries and 11 other countries in the Caribbean and other parts of the world.[67]

Transport

[edit]

Saint Kitts and Nevis has two international airports. The larger one is Robert L. Bradshaw International Airport on the island of Saint Kitts with service outside to the Caribbean, North America, and Europe. The other airport, Vance W. Amory International Airport, is located on the island of Nevis and has flights to other parts of the Caribbean.

The St Kitts Scenic Railway is the last remaining running railroad in the Lesser Antilles.

Economic citizenship by investment

[edit]St. Kitts and Nevis allows foreigners to obtain the status of St. Kitts and Nevis citizen by means of a government sponsored investment programme called Citizenship-by-Investment.[68][1] Established in 1984, St. Kitts and Nevis's citizenship programme is the oldest prevailing economic citizenship programme of this kind in the world. However, while the programme is the oldest in the world, it only catapulted in 2006 when Henley & Partners, a global citizenship advisory firm, became involved in the restructuring of the programme to incorporate donations to the country's sugar industry.[69]

Citizenship-by-Investment Programmes have been criticised by some researchers due to the risks of corruption, money laundering and tax evasion.[70] According to the official website of St. Kitts and Nevis's Citizenship-by-Investment Programme, they offer multiple benefits, including citizenship for life that can be passed down for generations, no residency or language requirements, and citizenship in a financially favourable country.[71] Once an applicant is vetted and successfully becomes a citizen, he or she is eligible to apply for a Saint Kitts and Nevis passport.[72]

To qualify for citizenship under the investment programme, each candidate must complete a vetting process which includes several background and due diligence checks, an interview, and other various legal requirements. This is followed by a qualifying investment into the country.[73] The applicant must make at least a minimum investment in either approved real estate; or a donation, known as the Sustainable Island State Contribution (SISC) into the Federal Consolidated Fund; or a donation to an Approved Public Benefactor.[73][71][74]

The official website of St. Kitts and Nevis's Citizenship-by-Investment Programme lists the following investment options:

- An investment in designated real estate with a minimum value of US$400,000, plus the payment of government fees and other fees and taxes.[73][74][75][76]

- A contribution to the Federal Consolidated Fund, or to an Approved Public Benefactor, of at least US$250,000, inclusive of all government fees but exclusive of due diligence fees which are the same as the real estate option.[73][71]

Education

[edit]There are eight publicly administered high and secondary level schools in St. Kitts and Nevis, and several private secondary schools. Education is compulsory between the ages of 5 and 16.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "CIA World Factbook- St Kitts and Nevis". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "National Profiles". Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "World Economic Outlook October 2023 (Saint Kitts and Nevis)". International Monetary Fund. October 2023. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "1983 Saint Kitts and Nevis Constitution". pdba.georgetown.edu. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Enclopedia Britannica – St Kitts and Nevis". Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Adkins, Leonard M. (1999). The Caribbean : a walking and hiking guide (3rd ed.). Edison, NJ: Hunter Pub. p. 178. ISBN 0585042586. OCLC 43474982.

- ^ a b Saunders, Nicholas J. (2005). Peoples of the Caribbean: an encyclopedia of archeology and traditional culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 260–261. ISBN 1576077012. OCLC 62090786.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20220810105128/https://best-citizenships.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/skn.jpg

https://archive.today/20230729090230/https://best-citizenships.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/skn.jpg - ^ See for example Nevis Heritage excavation reports, 2000–2002 Archived 8 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hubbard, Vincent (2002). A History of St. Kitts. Macmillan Caribbean. ISBN 9780333747605.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Commonwealth – History of St Kitts and Nevis". Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Patrick; et al., eds. (2010). The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions, Volume 1 A-L. Urbana, IL, Chicago, IL, and Springfield, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 886.

- ^ Cobley, 1994, p. 28.

- ^ a b Cobley, 1994, p. 27.

- ^ Jonnard, Claude M. (2010). Islands in the Wind: The Political Economy of the English East Caribbean. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse. p. number not available.

- ^ Du Tertre, Jean-Baptiste. Histoire générale des Antilles habitées par les François, 2 vols. Paris: Jolly, 1667, I:5–6.

- ^ "Treaty between Great Britain and Spain for the settlement of all disputes in America". The National Archives. gov.uk. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b c Hubbard, Vincent (2002). Swords, Ships & Sugar. Corvallis: Premiere Editions International, Inc. ISBN 9781891519055.

- ^ "St Kitts History". Beyondships Cruise Destinations. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Press. p. 17. ISBN 1-59420-009-2. OCLC 53083988.

- ^ Paravisini-Gebert, p.104

- ^ Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (2005). "Bradshaw, Robert Llewellyn". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. p. 606. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9.

- ^ Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I, pp576-578 ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ Minahan, James (2013). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems. Abc-Clio. pp. 656–657. ISBN 9780313344978.

- ^ See section 3 and 4 about Nevis Island Legislature and Administration in The Saint Christopher and Nevis Constitution Order 1983. Published online by Georgetown University Archived 20 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine and also by University of the West Indies Archived 10 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- ^ Nevis (St Kitts and Nevis), 18 August 1977: Separation from St Kitts Archived 10 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine Direct Democracy (in German)

- ^ General Election in St Kitts and Nevis 3 July 1995: The Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group. Commonwealth Observer Group, Commonwealth Secretariat, 1995. ISBN 0-85092-466-9, p.3.

- ^ "Nevis islanders apparently vote not to break away". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Associated Press. 11 August 1998.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Caribbean, Dominican Republic, Haiti - Hurricane Georges Fact Sheet #6 - Antigua and Barbuda". ReliefWeb. 30 September 1998. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Team Unity wins St Kitts and Nevis 2015 general election Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Caribbean Elections, 17 February 2015

- ^ Reporter, WIC News (6 June 2020). "Election 2020 - Landslide victory for Team Unity in St Kitts and Nevis". WIC News. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Salmon, Santana (8 August 2022). "St. Kitts Nevis new PM sworn into office". CNW Network.

- ^ "Art. 1, Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis Constitutional Order of 1983". Pdba.georgetown.edu. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "Commonwealth and Overseas". The Royal Family. 18 February 2016. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ OAS (1 August 2009). "OAS – Organization of American States: Democracy for peace, security, and development". Oas.org. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ a b c "Legal Supplement Part B – Vol. 33, No. 273 – 28th December, 1994 : LEGAL NOTICE NO. 232 : REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO THE INCOME TAX ACT, CHAP. 75:01 : ORDER MADE BY THE PRESIDENT UNDER SECTION 93(1) OF THE INCOME TAX ACT : THE DOUBLE TAXATION RELIEF (CARICOM) ORDER, 1994" (PDF). Ird.gov.tt. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA)". Treasury.gov. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Clarke, Sherrylyn (29 August 2022). "Eastern Caribbean court strikes down anti-buggery law". NationNews. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "St. Kitts and Nevis has no mandate to repeal homosexuality laws". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ a b "Homepage". Uscis.gov. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Denis Lepage (9 January 2013). "Avibase – Bird Checklists of the World Saint Kitts". Avibase. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ "Saint Kitts and Nevis Flora and Fauna". 23 December 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "Climate of Saint Kitts and Nevis: Temperature, Climograph, Climate table for Saint Kitts and Nevis – Climate-Data.org". Climate-data.org. Alexander Merkel. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Country Historical Climate – St. Kitts & Nevis". Climate Change Knowledge Portal. The World Bank Group. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Data on St. Kitts and Nevis | Reconstructing Global Inequality". clio-infra.eu. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Countries in the World by Population (2023)". Worldometer. 16 July 2023. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Table 5: Estimates of Mid-year Population: 2007–2016" (PDF). United Nations Demographic Yearbook: 2016. United Nations. 2017. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Population by Religious Belief, 2011". Department of Statistics, Ministry of Sustainable Development. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "CARICOM CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (CCDP) : 2000 ROUND OF POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS SUB-PROJECT NATIONAL CENSUS REPORT : ST. KITTS AND NEVIS". Caricomstats.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Section I. Religious Demography 2020 Report on International Religious Freedom: Saint Kitts and Nevis". Archived from the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Cameron, pg.502

- ^ "Missing in Action 2-The Beginning Review". Movies.tvguide.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ "St Kitts ramps up to host ICC Cricket World Cup in 2007". Caribbean.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Cricket World Cup 2007 - St. Kitts and Nevis". www.worldcup.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Soccer Star Marcus Rashford Puts Smile on Faces of Hungry Children". 5 September 2020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021.

- ^ "Dead Mad | by Cole Palmer". 14 July 2022. Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ Oinam, Jayanta. "Saint Kitts and Nevis: Sugar Boyz make history at CONCACAF Gold Cup". FIFA.com. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Bronze medalists of Saint Kitts and Nevis team Jason Rogers, Kim Collins, Antoine Adams and Brijesh Lawrence (L to R) react on the podium during the award ceremony for the men's 4x100 metres relay at the". sknvibes. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "E-ticket: So You Wanna Be An Olympian, Part 13". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Rob Jones (30 September 2010). "UCI Road World Championships 2010: Elite Men Results - Cyclingnews.com". Cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "St.Kitts-Nevis and the Republic of Ireland sign Tax Agreement". Ntltrust.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Citizenship-by-Investment Introduction". Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Abrahamian, Atossa Araxia (2015). The Cosmopolites: The Coming of the Global Citizen. Columbia Global Reports. ISBN 978-0-9909763-6-3.

- ^ Shachar, Ayelet (2017). Citizenship for Sale? In: The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship. Oxford University Press. pp. 789–816. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198805854.013.34. S2CID 168914434.

- ^ a b c St. Kitts and Nevis Government. (2023, July 27). Sustainable Island State Contribution (SISC). Ciu.Gov.Kn. Retrieved July 28, 2023, from https://ciu.gov.kn/investment-options/sustainable-island-state-contribution-sisc/.

https://web.archive.org/web/20230728101553/https://ciu.gov.kn/investment-options/sustainable-island-state-contribution-sisc/ - ^ Henley & Partners Holdings Ltd. (2023). St. Kitts and Nevis. Henleyglobal.com. https://web.archive.org/web/20230929173136/https://www.henleyglobal.com/citizenship-investment/st-kitts-nevis

"The Certificate of Registration confers citizenship status and once it has been issued, the applicant is entitled to apply for a passport" - ^ a b c d St. Kitts And Nevis Government Press Release. (2023, July 27). St Kitts and Nevis announces further monumental changes to its Citizenship by Investment Programme. St. Kitts And Nevis Government. Retrieved July 28, 2023, from https://ciu.gov.kn/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SKN-Press-Release-SKN-CBI-July_2023_Final.pdf.

https://web.archive.org/web/20230728095706/https://ciu.gov.kn/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SKN-Press-Release-SKN-CBI-July_2023_Final.pdf - ^ a b St. Kitts and Nevis Government. (2023, July). CBI Options. Retrieved July 29, 2023, from https://ciu.gov.kn/investment-options/

https://web.archive.org/web/20230729072552/https://ciu.gov.kn/investment-options/ - ^ Kalin, Christian H. (2015). Global Residence and Citizenship Handbook. Ideos Publications. ISBN 978-0992781859.

- ^ "Citizenship Investment in St. Kitts and Nevis - Henley & Partners". Henleyglobal.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Cobley, Alan Gregor; Department, University of the West Indies (Cave Hill, Barbados). History (1994). Crossroads of Empire: The European-Caribbean Connection, 1492–1992. Department of History, University of the West Indies. ISBN 978-976-621-031-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Government

- Saint Kitts & Nevis official government site

- Saint Kitts & Nevis Citizenship by Investment Program

- Saint Kitts & Nevis official Investment Promotion Agency

- Saint Kitts & Nevis St Kitts Financial Services Regulatory Commission

- Saint Kitts & Nevis Citizenship Program

- General information

- Saint Kitts and Nevis. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Saint Kitts and Nevis from OCB Libraries GovPubs

- Maps

- GeoHack list of street, satellite, and topographic maps

- Caribbean-On-Line, St Kitts & Nevis Maps

Wikimedia Atlas of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Tourism

- Nevis Tourism Authority – official site

- Saint Kitts Tourism Authority – official site

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Countries in the Caribbean

- Island countries

- Countries and territories where English is an official language

- Federal monarchies

- Member states of the Caribbean Community

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Member states of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

- Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas

- States and territories established in 1983

- Member states of the United Nations

- Small Island Developing States

- 1983 establishments in North America

- British Leeward Islands in World War II

- Countries in North America