Names of China

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Names of China |

|---|

|

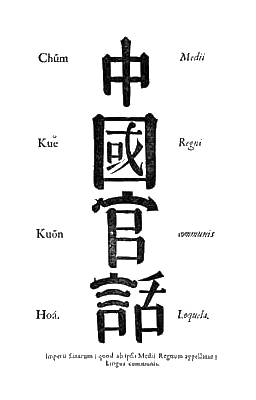

The names of China include the many contemporary and historical designations given in various languages for the East Asian country known as Zhōngguó (中国; 中國; 'Central State', 'Middle Kingdom') in Standard Chinese, a form based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin.

The English name "China" was borrowed from Portuguese during the 16th century, and its direct cognates became common in the subsequent centuries in the West.[2] It is believed to be a borrowing from Middle Persian, and some have traced it further back to the Sanskrit word चीन (cīna) for the nation. It is also thought that the ultimate source of the name China is the Chinese word Qín (秦), the name of the Qin dynasty that ultimately unified China after existing as a state within the Zhou dynasty for many centuries prior. However, there are alternative suggestions for the etymology of this word.

Chinese names for China, aside from Zhongguo, include Zhōnghuá (中华; 中華; 'central beauty'), Huáxià (华夏; 華夏; 'beautiful grandness'), Shénzhōu (神州; 'divine state') and Jiǔzhōu (九州; 'nine states'). While official notions of Chinese nationality do not make any particular reference to ethnicity, common names for the largest ethnic group in China are Hàn (汉; 漢) and Táng (唐). The People's Republic of China (Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó) and the Republic of China (Zhōnghuá Mínguó) are the official names of the two governments presently claiming sovereignty over "China". The term "mainland China" is used to refer to areas under the PRC's jurisdiction, either including or excluding Hong Kong and Macau.

There are also names for China used around the world that are derived from the languages of ethnic groups other than Han Chinese: examples include "Cathay" from the Khitan language, and Tabgach from Tuoba. The realm ruled by the Emperor of China is also referred to as Chinese Empire.

Sinitic names

[edit]

Zhongguo

[edit]Pre-Qing

[edit]

Zhōngguó (中國) is the most common Chinese name for China in modern times. The earliest appearance of this two-character term is on the bronze vessel He zun (dating to 1038–c. 1000 BCE), during the early Western Zhou period. The phrase "zhong guo" came into common usage in the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), when it referred to the "Central States", the states of the Yellow River Valley of the Zhou era, as distinguished from the tribal periphery.[3] In later periods, however, Zhongguo was not used in this sense. Dynastic names were used for the state in Imperial China, and concepts of the state aside from the ruling dynasty were little understood.[2] Rather, the country was called by the name of the dynasty, such as "Han", "Tang", "Great Ming", "Great Qing", etc. Until the 19th century, when the international system began to require common legal language, there was no need for a fixed or unique name.[4]

As early as the Spring and Autumn period, Zhongguo could be understood as either the domain of the capital or used to refer to the Chinese civilization zhūxià (諸夏; 'the various Xia')[5][6] or zhūhuá (諸華; 'various Hua'),[7][8] and the political and geographical domain that contained it, but Tianxia was the more common word for this idea. This developed into the usage of the Warring States period, when, other than the cultural community, it could be the geopolitical area of Chinese civilization, equivalent to Jiuzhou. In a more limited sense, it could also refer to the Central Plain or the states of Zhao, Wei, and Han, etc., geographically central among the Warring States.[9] Although Zhongguo could be used before the Song dynasty period to mean the trans-dynastic Chinese culture or civilization to which Chinese people belonged, it was in the Song dynasty that writers used Zhongguo as a term to describe the trans-dynastic entity with different dynastic names over time but having a set territory and defined by common ancestry, culture, and language.[10]

There were different usages of the term Zhongguo in every period. It could refer to the capital of the emperor to distinguish it from the capitals of his vassals, as in Western Zhou. It could refer to the states of the Central Plain to distinguish them from states in the outer regions. The Shi Jing defines Zhongguo as the capital region, setting it in opposition to the capital city.[11][12] During the Han dynasty, three usages of Zhongguo were common. The Records of the Grand Historian use Zhongguo to denote the capital[13][14] and also use the concepts zhong ("center, central") and zhongguo to indicate the center of civilization: "There are eight famous mountains in the world: three in Man and Yi (the barbarian wilds), five in Zhōngguó." (天下名山八,而三在蠻夷,五在中國。)[15][16] In this sense, the term Zhongguo is synonymous with Huáxià (华夏; 華夏) and Zhōnghuá (中华; 中華), names of China that were first authentically attested in the Warring States period[17] and Eastern Jin period,[18][19] respectively.

From the Qin to the Ming dynasty, literati discussed Zhongguo as both a historical place or territory and as a culture. Writers of the Ming period in particular used the term as a political tool to express opposition to expansionist policies that incorporated foreigners into the empire.[21] In contrast foreign conquerors typically avoided discussions of Zhongguo and instead defined membership in their empires to include both Han and non-Han peoples.[22]

Qing

[edit]Zhongguo appeared in a formal international legal document for the first time during the Qing dynasty in the Treaty of Nerchinsk, 1689. The term was then used in communications with other states and in treaties. The Manchu rulers incorporated Inner Asian polities into their empire, and Wei Yuan, a statecraft scholar, distinguished the new territories from Zhongguo, which he defined as the 17 provinces of "China proper" plus the Manchu homelands in the Northeast. By the late 19th century the term had emerged as a common name for the whole country. The empire was sometimes referred to as Great Qing but increasingly as Zhongguo (see the discussion below).[23]

Dulimbai Gurun is the Manchu name for China, with "Dulimbai" meaning "central" or "middle" and "Gurun" meaning "nation" or "state".[24][25][26] The historian Zhao Gang writes that "not long after the collapse of the Ming, China became the equivalent of Great Qing (Da Qing)—another official title of the Qing state," and "Qing and China became interchangeable official titles, and the latter often appeared as a substitute for the former in official documents."[27] The Qing dynasty referred to their realm as "Dulimbai Gurun" in Manchu. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing realm (including present-day Manchuria, Xinjiang, Mongolia, Tibet, and other areas) as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state, rejecting the idea that China only meant Han areas; both Han and non-Han peoples were part of "China".. Officials used "China" (though not exclusively) in official documents, international treaties, and foreign affairs, and the "Chinese language" (Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i bithe) referred to Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol languages, and the term "Chinese people" (中國人; Zhōngguórén; Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) referred to all Han, Manchus, and Mongol subjects of the Qing.[28] Ming loyalist Han literati held to defining the old Ming borders as China and using "foreigner" to describe minorities under Qing rule such as the Mongols and Tibetans, as part of their anti-Qing ideology.[29]

When the Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land was absorbed into Dulimbai Gurun in a Manchu language memorial.[30][31][32] The Qing expounded on their ideology that they were bringing together the "outer" non-Han Chinese, like the Inner Mongols, Eastern Mongols, Oirat Mongols, and Tibetans, together with the "inner" Han Chinese, into "one family" united in the Qing state, showing that the diverse subjects of the Qing were all part of one family. The Qing used the phrase "Zhōngwài yījiā" (中外一家; 'China and other [countries] as one family') or "Nèiwài yījiā" (內外一家; 'Interior and exterior as one family'), to convey this idea of "unification" of the different peoples.[33] A Manchu-language version of a treaty with the Russian Empire concerning criminal jurisdiction over bandits called people from the Qing "people of the Central Kingdom (Dulimbai Gurun)".[34][35][36][37] In the Manchu official Tulisen's Manchu language account of his meeting with the Torghut Mongol leader Ayuki Khan, it was mentioned that while the Torghuts were unlike the Russians, the "people of the Central Kingdom" (dulimba-i gurun/中國; Zhōngguó) were like the Torghut Mongols, and the "people of the Central Kingdom" referred to the Manchus.[38]

The geography textbooks published in the late Qing period gave detailed descriptions of China's regional position and territorial space. They generally emphasized that China was a large country in Asia, but not the center of the world. For example, the "Elementary Chinese Geography Textbook" (蒙學中國地理教科書) published in 1905 described the boundaries of China's territory and neighboring countries as follows: "The western border of China is located in the center of Asia, bordering the (overseas) territories of Britain and Russia. The terrain is humped, like a hat. So all mountains and rivers originate from here. To the east, it faces Japan across the East China Sea. To the south, it is adjacent to the South China Sea, and borders French Annam and British Burma. To the southwest, it is separated from British India by mountains. From the west to the north and the northeast, the three sides of China are all Russian territories. Only the southern border of the northeast is connected to Korea across the Yalu River." It further stated that "There are about a dozen countries in Asia, but only China has a vast territory, a prosperous population, and dominates East Asia. It is a great and world-famous country."[39]

The Qing enacted the first Chinese nationality law in 1909, which defined a Chinese national (Chinese: 中國國籍; pinyin: Zhōngguó Guójí) as any person born to a Chinese father. Children born to a Chinese mother inherited her nationality only if the father was stateless or had unknown nationality status.[40] These regulations were enacted in response to a 1907 statute passed in The Netherlands that retroactively treated all Chinese born in the Dutch East Indies as Dutch citizens. Jus sanguinis was chosen to define Chinese nationality so that the Qing could counter foreign claims on overseas Chinese populations and maintain the perpetual allegiance of its subjects living abroad through paternal lineage.[40] A Chinese word called xuètǒng (血統), which means "bloodline" as a literal translation, is used to explain the descent relationship that would characterize someone as being of Chinese descent and therefore eligible under the Qing laws and beyond, for Chinese citizenship.[41]

Mark Elliott noted that it was under the Qing that "China" transformed into a definition of referring to lands where the "state claimed sovereignty" rather than only the Central Plains area and its people by the end of the 18th century.[42]

Elena Barabantseva also noted that the Manchu referred to all subjects of the Qing empire regardless of ethnicity as "Chinese" (中國之人; Zhōngguó zhī rén; 'China's person'), and used the term (中國; Zhōngguó) as a synonym for the entire Qing empire while using 漢人; Hànrén) to refer only to the core area of the empire, with the entire empire viewed as multiethnic.[43]

William T. Rowe wrote that the name "China" (中華; 中國) was apparently understood to refer to the political realm of the Han Chinese during the Ming dynasty, and this understanding persisted among the Han Chinese into the early Qing dynasty, and the understanding was also shared by Aisin Gioro rulers before the Ming–Qing transition. The Qing, however, "came to refer to their more expansive empire not only as the Great Qing but also, nearly interchangeably, as China" within a few decades of this development. Instead of the earlier (Ming) idea of an ethnic Han Chinese state, this new Qing China was a "self-consciously multi-ethnic state".. Han Chinese scholars had some time to adapt this, but by the 19th century, the notion of China as a multinational state with new, significantly extended borders had become the standard terminology for Han Chinese writers. Rowe noted that "these were the origins of the China we know today.". He added that while the early Qing rulers viewed themselves as multi-hatted emperors who ruled several nationalities "separately but simultaneously", by the mid-19th century, the Qing Empire had become part of a European-style community of sovereign states and entered into a series of treaties with the West, and such treaties and documents consistently referred to Qing rulers as the "Emperor of China" and his administration as the "Government of China".[44]

Joseph W. Esherick noted that while the Qing Emperors governed frontier non-Han areas in a different, separate system under the Lifanyuan and kept them separate from Han areas and administration, it was the Manchu Qing Emperors who expanded the definition of Zhongguo and made it "flexible" by using that term to refer to the entire Empire and using that term to other countries in diplomatic correspondence, while some Han Chinese subjects criticized their usage of the term and the Han literati Wei Yuan used Zhongguo only to refer to the seventeen provinces of China and three provinces of the east (Manchuria), excluding other frontier areas.[45] Due to Qing using treaties clarifying the international borders of the Qing state, it was able to inculcate in the Chinese people a sense that China included areas such as Mongolia and Tibet due to education reforms in geography, which made it clear where the borders of the Qing state were, even if they didn't understand how the Chinese identity included Tibetans and Mongolians or what the connotations of being Chinese were.[46] The English version of the 1842 Treaty of Nanking refers to "His Majesty the Emperor of China" while the Chinese refers both to "The Great Qing Emperor" (Da Qing Huangdi) and to Zhongguo as well. The 1858 Treaty of Tientsin has similar language.[4]

In the late 19th century, the reformer Liang Qichao argued in a famous passage that "our greatest shame is that our country has no name. The names that people ordinarily think of, such as Xia, Han, or Tang, are all the titles of bygone dynasties." He argued that the other countries of the world "all boast of their own state names, such as England and France, the only exception being the Central States",[47] and that the concept of tianxia had to be abandoned in favor of guojia, that is, "nation", for which he accepted the term Zhongguo.[48] On the other hand, American Protestant missionary John Livingstone Nevius, who had been in China for 40 years, wrote in his 1868 book that the most common name which the Chinese used in speaking of their country was Zhongguo, followed by Zhonghuaguo (中華國) and other names such as Tianchao (天朝) and the particular title of the reigning dynasty.[49][50] Also, the Chinese geography textbook published in 1907 stated that "Chinese citizens call their country Zhongguo or Zhonghua", and noted that China (Zhongguo) was one of the few independent monarchical countries in the whole Asia at that time, along with countries like Japan.[51] The Japanese term "Shina" was once proposed by some as a basically neutral Western-influenced equivalent for "China". But after the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, Zhongguo was also adopted as the abbreviation of Zhonghua minguo,[52] and most Chinese considered Shina foreign and demanded that even the Japanese replace it with Zhonghua minguo, or simply Zhongguo.[53]

Before the signing of the Sino-Japanese Friendship and Trade Treaty in 1871, the first treaty between Qing China and the Empire of Japan, Japanese representatives once raised objections to China's use of the term Zhongguo in the treaty (partly in response to China's earlier objections for the term Tennō or Emperor of Japan to be used in the treaty), declaring that the term Zhongguo was "meant to compare with the frontier areas of the country" and insisted that only "Great Qing" be used for the Qing in the Chinese version of the treaty. However, this was firmly rejected by the Qing representatives: "Our country China has been called Zhongguo for a long time since ancient times. We have signed treaties with various countries, and while Great Qing did appear in the first lines of such treaties, in the body of the treaties Zhongguo was always being used. There has never been a precedent for changing the country name" (我中華之稱中國,自上古迄今,由來已久。即與各國立約,首書寫大清國字樣,其條款內皆稱中國,從無寫改國號之例). The Chinese representatives believed that Zhongguo (China) as a country name equivalent to "Great Qing" could naturally be used internationally, which could not be changed. In the end, both sides agreed that while in the first lines "Great Qing" would be used, whether the Chinese text in the body of the treaty would use the term Zhongguo in the same manner as "Great Qing" would be up to China's discretion.[50][54]

Qing official Zhang Deyi once objected to the western European name "China" and said that China referred to itself as Zhonghua in response to a European who asked why Chinese used the term guizi to refer to all Europeans.[55] However, the Qing established legations and consulates known as the "Chinese Legation", "Imperial Consulate of China", "Imperial Chinese Consulate (General)" or similar names in various countries with diplomatic relations, such as the United Kingdom and United States. Both English and Chinese terms, such as "China" and "Zhongguo", were frequently used by Qing legations and consulates there to refer to the Qing state during their diplomatic correspondences with foreign states.[56] Moreover, the English name "China" was also used domestically by the Qing, such as in its officially released stamps since Qing set up a modern postal system in 1878. The postage stamps (known as 大龍郵票 in Chinese) had a design of a large dragon in the centre, surrounded by a boxed frame with a bilingual inscription of "CHINA" (corresponding to the Great Qing Empire in Chinese) and the local denomination "CANDARINS".[57]

During the late Qing dynasty, various textbooks with the name "Chinese history" (中國歷史) had emerged by the early 20th century. For example, the late Qing textbook "Chinese History of the Present Dynasty" published in 1910 stated that "the history of our present dynasty is part of the history of China, that is, the most recent history in its whole history. China was founded as a country 5,000 years ago and has the longest history in the world. And its culture is the best among all the Eastern countries since ancient times. Its territory covers about 90% of East Asia, and its rise and fall can affect the general trend of the countries in Asia...".[50][58] After the May Fourth Movement in 1919, educated students began to spread the concept of Zhonghua, which represented the people, including 55 minority ethnic groups and the Han Chinese, with a single culture identifying themselves as "Chinese". The Republic of China and the People's Republic of China both used Zhonghua in their official names. Thus, Zhongguo became the common name for both governments and Zhōngguó rén (中国人; 中國人) for their citizens. Overseas Chinese are referred to as huáqiáo (华侨; 華僑; 'Chinese overseas'), or huáyì (华裔; 華裔; 'Chinese descendants'), i.e. Chinese children born overseas.

Middle Kingdom

[edit]The English translation of Zhongyuan as the "Middle Kingdom" entered European languages through the Portuguese in the 16th century and became popular in the mid-19th century. By the mid-20th century, the term was thoroughly entrenched in the English language, reflecting the Western view of China as the inward-looking Middle Kingdom, or more accurately, the Central Kingdom or Central State. Endymion Wilkinson points out that the Chinese were not unique in thinking of their country as central, although China was the only culture to use the concept for its name.[59] However, the term Zhongguo was not initially used as a name for China. It did not have the same meaning throughout the course of history (see above).[60]

During the 19th century, China was alternatively (although less commonly) referred to in the west as the "Middle Flowery Kingdom",[61] "Central Flowery Kingdom",[62] or "Central Flowery State",[63] translated from Zhōnghuáguó (中華國; 中华国),[64] or simply the "Flowery Kingdom",[65] translated from Huáguó (華國; 华国).[66][67] However, some have since argued that such a translation (fairly commonly seen at that time) was perhaps caused by misunderstanding the Huá (華; 华) that means "China" (or "magnificent, splendid") for the Huā (花) that means "flower".[68][69]

Huaxia

[edit]The name Huáxià (华夏; 華夏) is generally used as a sobriquet in Chinese text. Under traditional interpretations, it is the combination of two words which originally referred to the elegance of traditional Han attire and the Confucian concept of rites.

- Hua, which means "flowery beauty" (i.e., having beauty of dress and personal adornment 有服章之美,謂之華).

- Xia, which means greatness or grandeur (i.e., having greatness in social customs, courtesy, polite manners and rites/ceremony 有禮儀之大,故稱夏).[70]

In the original sense, Huaxia refers to a confederation of tribes—living along the Yellow River—who were the ancestors of what later became the Han ethnic group in China.[citation needed] During the Warring States (475–221 BCE), the self-awareness of the Huaxia identity developed and took hold in ancient China.

Zhonghua minzu

[edit]Zhonghua minzu is a term meaning "Chinese nation" in the sense of a multi-ethnic national identity. Though originally rejected by the PRC, it has been used officially since the 1980s for nationalist politics.

Tianchao and Tianxia

[edit]Tianchao (天朝; pinyin: Tiāncháo), translated as 'heavenly dynasty' or 'Celestial Empire',[71] and Tianxia (天下; pinyin: Tiānxià) translated as 'All under heaven', have both been used to refer to China. These terms were usually used in the context of civil wars or periods of division, with the term Tianchao evoking the idea that the realm's ruling dynasty was appointed by heaven,[71] or that whoever ends up reunifying China is said to have ruled Tianxia, or everything under heaven. This fits with the traditional Chinese theory of rulership, in which the emperor was nominally the political leader of the entire world and not merely the leader of a nation-state within the world. Historically, the term was connected to the later Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE), especially the Spring and Autumn period (eighth to fourth century BCE) and the Warring States period (from there to 221 BCE, when China was reunified by Qin). The phrase Tianchao continues to see use on Chinese internet discussion boards, in reference to China.[71]

The phrase Tianchao was first translated into English and French in the early 19th century, appearing in foreign publications and diplomatic correspondences,[72] with the translated phrase "Celestial Empire" occasionally used to refer to China. During this period, the term celestial was used by some to refer to the subjects of the Qing in a non-prejudicial manner,[72] derived from the term "Celestial Empire". However, the term celestial was also used in a pejorative manner during the 19th century, in reference to Chinese immigrants in Australasia and North America.[72] The translated phrase has largely fallen into disuse in the 20th century.

Jiangshan and Shanhe

[edit]The two names Jiāngshān (江山) and Shānhé (山河), both literally 'rivers and mountains', quite similar in usage to Tianxia, simply referring to the entire world, the most prominent features of which being rivers and mountains. The use of this term is also common as part of the idiom Jiāngshān shèjì (江山社稷; 'rivers and mountains', 'soil and grain'), in a suggestion of the need to implement good governance.

Jiuzhou

[edit]The name jiǔ zhōu (九州) means 'nine provinces'. Widely used in pre-modern Chinese text, the word originated during the middle of the Warring States period. During that time, the Yellow River region was divided into nine geographical regions; thus this name was coined. Some people also attribute this word to the mythical hero and king Yu the Great, who, in the legend, divided China into nine provinces during his reign.

Han

[edit]| Han | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hàn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Hán | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 한 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 漢 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | かん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name Han (汉; 漢; Hàn) derives from the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220), which presided over China's first "golden age".. The Han dynasty collapsed in 220 and was followed by a long period of disorder, including Three Kingdoms, Sixteen Kingdoms, and Southern and Northern dynasties periods. During these periods, various non-Han ethnic groups established various dynasties in northern China. It was during this period that people began to use the term "Han" to refer to the natives of North China, who (unlike the minorities) were the descendants of the subjects of the Han dynasty.

During the Yuan dynasty, subjects of the empire were divided into four classes: Mongols, Semu, Han, and "Southerns". Northern Chinese were called Han, which was considered to be the highest class of Chinese. This class, "Han," includes all ethnic groups in northern China, including Khitan and Jurchen who have, for the most part, sinicized during the last two hundreds years. The name "Han" became popularly accepted.

During the Qing, the Manchu rulers also used the name Han to distinguish the natives of the Central Plains from the Manchus. After the fall of the Qing government, the Han became the name of a nationality within China. Today, the term "Han persons", often rendered in English as "Han Chinese", is used by the People's Republic of China to refer to the most populous of the 56 officially recognized ethnic groups in China.

Tang

[edit]| Tang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Táng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Đường | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 당 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 唐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | とう (On), から (Kun) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name Tang (唐; Táng) comes from the Tang dynasty (618–907) that presided over China's second golden age. It was during the Tang dynasty that South China was finally and fully sinicized; Tang would become synonymous with China in Southern China, and it is usually Southern Chinese who refer to themselves as "People of Tang" (唐人, pinyin: Tángrén).[73] For example, the sinicization and rapid development of Guangdong during the Tang period would lead the Cantonese to refer to themselves as Tong-yan (唐人) in Cantonese, while China is called Tong-saan (唐山; pinyin: Tángshān; lit. 'Tang Mountain').[74] Chinatowns worldwide, often dominated by Southern Chinese, also became referred to as Tang People's Street (唐人街, Cantonese: Tong-yan-gaai; pinyin: Tángrénjiē). The Cantonese term Tongsan (Tang mountain) is recorded in Old Malay as one of the local terms for China, along with the Sanskrit-derived Cina. It is still used in Malaysia today, usually in a derogatory sense.

Among Taiwanese, Tang mountain (Min-Nan: Tng-soa) has been used, for example, in the saying, "has Tangshan father, no Tangshan mother" (有唐山公,無唐山媽; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ū Tn̂g-soaⁿ kong, bô Tn̂g-soaⁿ má).[75][76] This refers to how the Han people crossing the Taiwan Strait in the 17th and 18th centuries were mostly men, and that many of their offspring would be through intermarriage with Taiwanese aborigine women.

In Ryukyuan, karate was originally called tii (手, hand) or karatii (唐手, Tang hand) because 唐ぬ國 too-nu-kuku or kara-nu-kuku (唐ぬ國) was a common Ryukyuan name for China; it was changed to karate (空手, open hand) to appeal to Japanese people after the First Sino-Japanese War.

Zhu Yu, who wrote during the Northern Song dynasty, noted that the name "Han" was first used by the northwestern 'barbarians' to refer to China, while the name "Tang" was first used by the southeastern 'barbarians' to refer to China, and these terms subsequently influenced the local Chinese terminology.[77] During the Mongol invasions of Japan, the Japanese distinguished between the "Han" of northern China, who, like the Mongols and Koreans, were not to be taken prisoner, and the Newly Submitted Army of southern China, whom they called "Tang", who would be enslaved instead.[78]

Dalu and Neidi

[edit]Dàlù (大陸/大陆; pinyin: dàlù), literally "big continent" or "mainland" in this context, is used as a short form of Zhōnggúo Dàlù (中國大陸/中国大陆, mainland China), excluding (depending on the context) Hong Kong, Macau, or Taiwan. This term is used in official contexts on both the mainland and Taiwan when referring to the mainland as opposed to Taiwan. In certain contexts, it is equivalent to the term Neidi (内地; pinyin: nèidì, literally "the inner land"). While Neidi generally refers to the interior as opposed to a particular coastal or border location, or the coastal or border regions generally, it is used in Hong Kong specifically to mean mainland China, excluding Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Increasingly, it is also being used in an official context within mainland China[citation needed], for example, in reference to the separate judicial and customs jurisdictions of mainland China on the one hand and Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan on the other.

The term Neidi is also often used in Xinjiang and Tibet to distinguish the eastern provinces of China from the minority-populated, autonomous regions of the west.

Official names

[edit]People's Republic of China

[edit]| People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"People's Republic of China" in simplified (top) and traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华人民共和国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華人民共和國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་མི་དམངས་སྤྱི མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Cộng hoà Nhân dân Trung Hoa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 共和人民中華 / 中華人民共和国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | สาธารณรัฐประชาชนจีน | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghvaz Yinzminz Gunghozgoz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 중화 인민 공화국 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 中華人民共和国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Бүгд Найрамдах Дундад Ард Улс | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠪᠦᠭᠦᠳᠡ ᠨᠠᠶᠢᠷᠠᠮᠳᠠᠬᠤ ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 中華人民共和国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭخۇا خەلق جۇمھۇرىيىتى | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠯᠮᠠᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᠨᡥᡝ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai niyalmairgen gunghe' gurun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The name New China has been frequently applied to China by the Chinese Communist Party as a positive political and social term contrasting pre-1949 China (the establishment of the PRC) and the new name of the socialist state, Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó (in the older postal romanization, Chunghwa Jenmin Konghokuo), or the "People's Republic of China" in English, which was adapted from the CCP's short-lived Chinese Soviet Republic in 1931. This term is also sometimes used by writers outside of mainland China. The PRC was known to many in the West during the Cold War as "Communist China" or "Red China" to distinguish it from the Republic of China which is commonly called "Taiwan", "Nationalist China", or "Free China". In some contexts, particularly in economics, trade, and sports, "China" is often used to refer to mainland China to the exclusion of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Republic of China

[edit]| Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Republic of China" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chunghwa Minkuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Central State People's Country | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese Taipei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華臺北 or 中華台北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华台北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺澎金馬 個別關稅領域 or 台澎金馬 個別關稅領域 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台澎金马 个别关税领域 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣 or 台灣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Terraced Bay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese: (Ilha) Formosa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 福爾摩沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 福尔摩沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | beautiful island | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republic of Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣民國 or 台灣民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Taiwan Minkuo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀྲུང་ཧྭ་དམངས་གཙོའི། ་རྒྱལ་ཁབ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Trung Hoa Dân Quốc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | Cunghvaz Minzgoz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 중화민국 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 中華民國 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Дундад Иргэн Улс | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠳᠤᠮᠳᠠᠳᠤ ᠢᠷᠭᠡᠨ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 中華民国 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ちゅうかみんこく | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uyghur | جۇڭخۇا مىنگو | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ ᡳᡵᡤᡝᠨ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dulimbai irgen' Gurun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1912, China adopted its official name, Chunghwa Minkuo (rendered in pinyin Zhōnghuá Mínguó) or in English as the "Republic of China", which has also sometimes been referred to as "Republican China" or the "Republican Era" (民國時代), in contrast to the Qing dynasty it replaced, or as "Nationalist China", after the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang). 中華 (Chunghwa) is a term that pertains to "China", while 民國 (Minkuo), literally "People's State" or "Peopledom", stands for "republic"..[79][80] The name stems from the party manifesto of Tongmenghui in 1905, which says the four goals of the Chinese revolution were "to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive Chunghwa, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people. The convener of Tongmenghui and Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen proposed the name Chunghwa Minkuo as the assumed name of the new country when the revolution succeeded.

Since the separation from mainland China in 1949 as a result of the Chinese Civil War, the territory of the Republic of China has largely been confined to the island of Taiwan and some other small islands. Thus, the country is often simply referred to as simply "Taiwan", although this may not be perceived as politically neutral. Amid the hostile rhetoric of the Cold War, the government and its supporters sometimes referred to themselves as "Free China" or "Liberal China", in contrast to the People's Republic of China, which was historically called the "Bandit-occupied Area" (匪區) by the ROC. In addition, the ROC, due to pressure from the PRC, uses the name "Chinese Taipei" (中華台北) whenever it participates in international forums or most sporting events such as the Olympic Games.

Taiwanese politician Mei Feng had criticised the official English name of the state, "Republic of China", for failing to translate the Chinese character "Min" (Chinese: 民; English: people) according to Sun Yat-sen's original interpretations, while the name should instead be translated as "the People's Republic of China", which confuses with the current official name of China under communist control.[81] To avoid confusion, the Chen Shui-ban led DPP administration began to add "Taiwan" next to the nation's official name since 2005.[82]

Names in non-Chinese records

[edit]Names used in the parts of Asia, especially East and Southeast Asia, are usually derived directly from words in one of the languages of China. Those languages belonging to a former dependency (tributary) or Chinese-influenced country have an especially similar pronunciation to that of Chinese. Those used in Indo-European languages, however, have indirect names that came via other routes and may bear little resemblance to what is used in China.

China

[edit]English, most Indo-European languages, and many others use various forms of the name China and the prefix "Sino-" or "Sin-" from the Latin Sina.[83][84] Europeans had knowledge of a country known in Greek as Thina or Sina from the early period;[85] the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea from perhaps the first century AD recorded a country known as Thin (θίν).[86] The English name for "China" itself is derived from Middle Persian (Chīnī چین). This modern word "China" was first used by Europeans starting with Portuguese explorers of the 16th century – it was first recorded in 1516 in the journal of the Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa.[87][88] The journal was translated and published in England in 1555.[89]

The traditional etymology, proposed in the 17th century by Martin Martini and supported by later scholars such as Paul Pelliot and Berthold Laufer, is that the word "China" and its related terms are ultimately derived from the polity known as Qin that unified China to form the Qin dynasty (Old Chinese: *dzin) in the 3rd century BC, but existed as a state on the furthest west of China since the 9th century BC.[85][90][91] This is still the most commonly held theory, although the etymology is still a matter of debate according to the Oxford English Dictionary,[92] and many other suggestions have been mooted.[93][94]

The existence of the word Cīna in ancient Indian texts was noted by the Sanskrit scholar Hermann Jacobi who pointed out its use in the Book 2 of Arthashastra with reference to silk and woven cloth produced by the country of Cīna, although textual analysis suggests that Book 2 may not have been written long before 150 AD.[95] The word is also found in other Sanskrit texts such as the Mahābhārata and the Laws of Manu.[96] The Indologist Patrick Olivelle argued that the word Cīnā may not have been known in India before the first century BC, nevertheless he agreed that it probably referred to Qin but thought that the word itself was derived from a Central Asian language.[97] Some Chinese and Indian scholars argued for the state of Jing (荆, another name for Chu) as the likely origin of the name.[94] Another suggestion, made by Geoff Wade, is that the Cīnāh in Sanskrit texts refers to an ancient kingdom centered in present-day Guizhou, called Yelang, in the south Tibeto-Burman highlands.[96] The inhabitants referred to themselves as Zina according to Wade.[98]

The term China can also be used to refer to:

- a modern state, indicating the PRC or ROC;

- "Mainland China" (中国大陆; 中國大陸; Zhōngguó Dàlù, which is the territory of the PRC minus the two regions of Hong Kong and Macau;

- "China proper", a term used to refer to the historical heartlands of China without peripheral areas like Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang

In economic contexts, "Greater China" (大中华地区; 大中華地區; Dà Zhōnghuá dìqū) is intended to be a neutral and non-political way to refer to mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

Sinologists usually use "Chinese" in a more restricted sense, akin to the classical usage of Zhongguo, to the Han ethnic group, which makes up the bulk of the population in China and of the overseas Chinese.

Seres, Ser, Serica

[edit]Sēres (Σῆρες) was the Ancient Greek and Roman name for the northwestern part of China and its inhabitants. It meant 'of silk', or 'land where silk comes from'. The name is thought to derive from the Chinese word for silk, 丝; 絲; sī; Middle Chinese sɨ, Old Chinese *slɯ, per Zhengzhang). It is itself at the origin of the Latin for 'silk', sērica.

This may be a back formation from sērikos (σηρικός), 'made of silk', from sēr (σήρ), 'silkworm', in which case Sēres is 'the land where silk comes from'.

Sinae, Sin

[edit]

Sīnae was an ancient Greek and Roman name for some people who dwelt south of Serica in the eastern extremity of the habitable world. References to the Sinae include mention of a city that the Romans called Sēra Mētropolis, which may be modern Chang'an. The Latin prefix Sino- as well as words such as Sinica, which are traditionally used to refer to China, came from Sīnae.[99] It is generally thought that Chīna, Sīna and Thīna are variants that ultimately derived from "Qin", the western Zhou-era state that eventually founded the Qin dynasty.[86] There are other opinions on its etymology: Henry Yule thought that this term may have come to Europe through the Arabs, who made the China of the farther east into Sin, and perhaps sometimes into Thin.[100] Hence the Thin of the author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, who appears to be the first extant writer to employ the name in this form; hence also the Sinae and Thinae of Ptolemy.[85][86]

Some denied that Ptolemy's Sinae really represented the Chinese as Ptolemy called the country Sērice and the capital Sēra, but regarded them as distinct from Sīnae.[86][101] Marcian of Heraclea, a condenser of Ptolemy, tells us that the "nations of the Sinae lie at the extremity of the habitable world, and adjoin the eastern Terra incognita". The 6th century Cosmas Indicopleustes refers to a "country of silk" called Tzinista, which is understood as referring to China, beyond which "there is neither navigation nor any land to inhabit".[102] It seems probable that the same region is meant by both. According to Henry Yule, Ptolemy's misrendering of the Indian Sea as a closed basin meant that Ptolemy must also have misplaced the Chinese coast, leading to the misconception of Serica and Sina as separate countries.[100]

In the Hebrew Bible, there is a mention of the faraway country "Sinim" in the Book of Isaiah 49:12 which some had assumed to be a reference to China.[86][103] In Genesis 10:17, a tribes called the "Sinites" were said to be the descendants of Canaan, the son of Ham, but they are usually considered to be a different people, probably from the northern part of Lebanon.[104][105]

Cathay or Kitay

[edit]These names derive from the Khitan people that originated in Manchuria and conquered parts of northern China during the early 10th century to form the Liao dynasty, and dominated Central Asia during the 12th century as the Kara Khitan Khanate. Due to the long period of political relevance, the name "Khitan" become associated with China. Muslim historians referred to the Kara Khitan state as "Khitay" or "Khitai"; they may have adopted this form of "Khitan" via the Uyghurs of Qocho, in whose language the final -n or -ń became -y.[106] The name was then introduced to medieval and early modern Europe through Islamic and Russian sources.[107] In English and in several other European languages, the name "Cathay" was used in the translations of the adventures of Marco Polo, which used this word for northern China. Words related to Khitay are still used in many Turkic and Slavic languages to refer to China. However, its use by Turkic speakers within China, such as the Uyghurs, is considered pejorative by the Chinese authority who tried to ban it.[107]

There is no evidence that either in the 13th or 14th century, Cathayans, i.e. Chinese, travelled officially to Europe, but it is possible that some did, in unofficial capacities, at least in the 13th century. During the campaigns of Hulagu (the grandson of Genghis Khan) in Persia (1256–65), and the reigns of his successors, Chinese engineers were employed on the banks of the Tigris, and Chinese astrologers and physicians could be consulted. Many diplomatic communications passed between the Hulaguid Ilkhans and Christian princes. The former, as the great khan's liegemen, still received from him their seals of state; and two of their letters which survive in the archives of France exhibit the vermilion impressions of those seals in Chinese characters—perhaps affording the earliest specimen of those characters to reach western Europe.

Tabgach

[edit]The word Tabgach came from the metatheses of Tuoba (*t'akbat), a dominant tribe of the Xianbei and the surname of the Northern Wei emperors in the 5th century before sinicisation. It referred to Northern China, which was dominated by part-Xianbei, part-Han people.

This name is re-translated back into Chinese as Taohuashi (Chinese: 桃花石; pinyin: táohuā shí).[108] This name has been used in China in recent years to promote ethnic unity.[109][110]

Nikan

[edit]Nikan (Manchu: ᠨᡳᡴᠠᠨ) was a Manchu ethnonym of unknown origin that referred specifically to the Han Chinese; the stem of this word was also conjugated as a verb, nikara(-mbi), which meant 'to speak the Chinese language'. Since Nikan was essentially an ethnonym and referred to a group of people rather than to a political body, the correct translation of "China" into Manchu is Nikan gurun, 'country of the Han'.[citation needed]

This exonym for the Han Chinese is also used in the Daur language, in which it appears as Niaken ([njakən] or [ɲakən]).[111] As in the case of the Manchu language, the Daur word Niaken is essentially an ethnonym, and the proper way to refer to the country of the Han Chinese (i.e., "China" in a cultural sense) is Niaken gurun, while niakendaaci- is a verb meaning "to talk in Chinese".

Kara

[edit]Japanese: Kara (から; variously written as 唐 or 漢). An identical name was used by the ancient and medieval Japanese to refer to the country that is now known as Korea, and many Japanese historians and linguists believe that the word "Kara" referring to China and/or Korea may have derived from a metonymic extension of the appellation of the ancient city-states of Gaya.

The Japanese word karate (空手, lit. "empty hand") is derived from the Okinawan word karatii (唐手, lit. "Chinese/Asian/foreign hand/trick/means/method/style") and refers to Okinawan martial arts; the character for kara was changed to remove the connotation of the style originating in China.[112]

Morokoshi

[edit]Japanese: Morokoshi (もろこし; variously written as 唐 or 唐土). This obsolete Japanese name for China is believed to have derived from a kun'yomi reading of the Chinese compound 諸越 Zhūyuè or 百越 Baiyue as "all the Yue" or "the hundred (i.e., myriad, various, or numerous) Yue," which was an ancient Chinese name for the societies of the regions that are now southern China.

The Japanese common noun tōmorokoshi (トウモロコシ, 玉蜀黍), which refers to maize, appears to contain an element cognate with the proper noun formerly used in reference to China. Although tōmorokoshi is traditionally written with Chinese characters that literally mean "jade Shu millet", the etymology of the Japanese word appears to go back to "Tang morokoshi", in which "morokoshi" was the obsolete Japanese name for China as well as the Japanese word for sorghum, which seems to have been introduced into Japan from China.

Mangi

[edit]

From Chinese Manzi (southern barbarians). The division of north and south China under the Jin dynasty and Song dynasty weakened the idea of a unified China, and it was common for non-Han peoples to refer to the politically disparate North and South by different names for some time. While Northern China was called Cathay, Southern China was referred to as Mangi. Manzi often appears in documents of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty as a disparaging term for Southern China. The Mongols also called Southern Chinese Nangkiyas or Nangkiyad, and considered them ethnically distinct from North Chinese. The word Manzi reached the Western world as Mangi (as used by Marco Polo), which is a name commonly found on medieval maps. Note however that the Chinese themselves considered Manzi to be derogatory and never used it as a self-appellation.[113][114] Some early scholars believed Mangi to be a corruption of the Persian Machin (ماچين) and Arabic Māṣīn (ماصين), which may be a mistake as these two forms are derived from the Sanskrit Maha Chin meaning Great China.[115]

Sungsong

[edit]In some Philippine languages, Sungsong or Sungsung was a historical and archaic name for China [116][117]. In Tiruray, the name meant specifically for Hong Kong [118]. The name comes from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian *suŋsuŋ, which meant "to go against wind or current". Its application to China in Philippine languages presumably is connected with sailing problems in reaching mainland China from the Philippines [119].

Sign names

[edit]The name for China in Chinese Sign Language is performed by trailing the tip of one's fingertip horizontally across the upper end of the chest, from the non-dominant side to the dominant one, and then vertically downwards.[120] Many sign languages have adopted the Chinese sign as a loanword; this includes American Sign Language,[121] in which this has happened across dialects, from Canada[122] to California,[123] replacing previous signs indicating East Asian people's typical epicanthic fold, now considered offensive.[124]

Multiple other languages have borrowed the sign as well, with some modifications. In Estonian Sign Language, the index finger moves diagonally to the non-dominant side instead of vertically downwards,[125] and in French[126] and Israeli Sign Language,[127] the thumb is used instead. Some other languages use unrelated signs.[128] For example, in Hong Kong Sign Language, the extended dominant index and middle fingers, held together, tap twice the non-dominant ones in the same handshape, palm downwards, in front of the signer's chest;[129] in Taiwanese Sign Language, both hands are flat, with extended thumbs and other fingers held together and pointing sideways, palms towards the signer, move up and down together repeatedly in front of the signer's chest.[130]

See also

[edit]- Little China (ideology)

- Chinese romanization

- List of country name etymologies

- Names of the Qing dynasty

- Names of India

- Names of Japan

- Names of Korea

- Names of Vietnam

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Bilik, Naran (2015), "Reconstructing China beyond Homogeneity", Patriotism in East Asia, Political Theories in East Asian Context, Abingdon: Routledge, p. 105

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2015, p. 191.

- ^ Esherick (2006), p. 232–233

- ^ a b Zarrow, Peter Gue (2012). After Empire: The Conceptual Transformation of the Chinese State, 1885–1924. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7868-8., p. 93-94 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Zuo Zhuan "Duke Min – 1st year – zhuan Archived 2022-04-29 at the Wayback Machine" quote: "諸夏親暱不可棄也" translation: "The various Xia are close intimates and can not be abandoned"

- ^ Du Yu, Chunqiu Zuozhuan – Collected Explanations, "Vol. 4" p. 136 of 186 Archived 2022-05-11 at the Wayback Machine. quote: "諸夏中國也"

- ^ Zuozhuan "Duke Xiang – 4th year – zhuan Archived 2022-04-29 at the Wayback Machine" quote: "諸華必叛" translation: "The various Hua would surely revolt"

- ^ Du Yu, Chunqiu Zuozhuan – Collected Explanations, "Vol. 15". p. 102 of 162 Archived 2022-05-11 at the Wayback Machine quote: "諸華中國"

- ^ Ban Wang. Chinese Visions of World Order: Tian, Culture and World Politics. pp. 270–272.

- ^ Tackett, Nicolas (2017). Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4, 161–2, 174, 194, 208, 280. ISBN 978-1-107-19677-3.

- ^ Classic of Poetry, "Major Hymns – Min Lu Archived 2022-04-12 at the Wayback Machine" quote: 《惠此中國、以綏四方。…… 惠此京師、以綏四國 。 " Legge's translation: "Let us cherish this center of the kingdom, to secure the repose of the four quarters of it. [...] Let us cherish this capital, to secure the repose of the States in the four quarters."

- ^ Zhu Xi (publisher, 1100s), Collected Commentaries on the Classic of Poetry (詩經集傳) "Juan A (卷阿)" Archived 2022-04-12 at the Wayback Machine p. 68 of 198 Archived 2022-04-12 at the Wayback Machine quote: "中國,京師也。四方,諸夏也。京師,諸夏之根本也。" translation: "The center of the kingdom means the capital. The 'four quarters' refer to the Huaxia. The capital is the root of the various Xia."

- ^ Shiji, "Annals of the Five Emperors" Archived 2022-05-10 at the Wayback Machine quote: "舜曰:「天也」,夫而後之中國踐天子位焉,是為帝舜。" translation: "Shun said, 'It is from Heaven.' Afterwards he went to the capital, sat on the Imperial throne, and was styled Emperor Shun."

- ^ Pei Yin, Records of the Grand Historian – Collected Explanation Vol. 1 "劉熈曰……帝王所都為中故曰中國" translation: "Liu Xi said: [...] Wherever emperors and kings established their capitals is taken as the center; hence the appellation the central region"

- ^ Shiji, "Annals of Emperor Xiaowu" Archived 2022-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shiji "Treatise about the Feng Shan sacrifices" Archived 2022-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zuo zhuan, "Duke Xiang, year 26, zhuan" Archived 2022-03-18 at the Wayback Machine text: "楚失華夏." translation: "Chu lost (the political allegiance of / the political influence over) the flourishing and grand (states)."

- ^ Huan Wen (347 CE). "Memorial Recommending Qiao Yuanyan" (薦譙元彥表), quoted in Sun Sheng's Annals of Jin (晉陽秋) (now-lost), quoted in Pei Songzhi's annotations to Chen Shou, Records of the Three Kingdoms, "Biography of Qiao Xiu" Archived 2022-04-04 at the Wayback Machine quote: "於時皇極遘道消之會,群黎蹈顛沛之艱,中華有顧瞻之哀,幽谷無遷喬之望。"

- ^ Farmer, J. Michael (2017) "Sanguo Zhi Fascicle 42: The Biography of Qiao Zhou", Early Medieval China, 23, 22-41, p. 39. quote: "At this time, the imperial court has encountered a time of decline in the Way, the peasants have been trampled down by oppressive hardships, Zhonghua has the anguish of looking backward [toward the former capital at Luoyang], and the dark valley has no hope of moving upward." DOI: 10.1080/15299104.2017.1379725

- ^ Fourmont, Etienne. "Linguae Sinarum Mandarinicae hieroglyphicae grammatica duplex, latinè, & cum characteribus Sinensium. Item Sinicorum Regiae Bibliothecae librorum catalogus… (A Chinese grammar published in 1742 in Paris)". Archived from the original on 2012-03-06.

- ^ Jiang 2011, p. 103.

- ^ Peter K Bol, "Geography and Culture: Middle-Period Discourse on the Zhong Guo: The Central Country," (2009), 1, 26.

- ^ Esherick (2006), pp. 232–233

- ^ Hauer 2007 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 117.

- ^ Dvořák 1895 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 80.

- ^ Wu 1995 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 102.

- ^ Zhao (2006), p. 7.

- ^ Zhao (2006), p. 4, 7–10, 12–14.

- ^ Mosca 2011 Archived 2018-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, p. 94.

- ^ Dunnell 2004 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 77.

- ^ Dunnell 2004 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 83.

- ^ Elliott 2001 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 503.

- ^ Dunnell 2004 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 76-77.

- ^ Cassel 2011 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 205.

- ^ Cassel 2012 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 205.

- ^ Cassel 2011 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 44.

- ^ Cassel 2012 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 44.

- ^ Perdue 2009 Archived 2023-04-11 at the Wayback Machine, p. 218.

- ^ "地理书写与国家认同:清末地理教科书中的民族主义话语". Sohu. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Shao, Dan (2009). "Chinese by Definition: Nationality Law, Jus Sanguinis, and State Succession, 1909–1980". Twentieth-Century China. 35 (1): 4–28. doi:10.1353/tcc.0.0019. S2CID 201771890.

- ^ Clayton, Cathryn H. (2010). Sovereignty at the Edge: Macau & the Question of Chineseness. Harvard University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-674-03545-4.

- ^ Elliot 2000 Archived 2018-08-03 at the Wayback Machine, p. 638.

- ^ Barabantseva 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Rowe, Rowe (2010). China's Last Empire – The Great Qing. Harvard University Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-0-674-05455-4. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ Esherick (2006), p. 232

- ^ Esherick (2006), p. 251

- ^ Liang quoted in Esherick (2006), p. 235, from Liang Qichao, "Zhongguo shi xulun" Yinbinshi heji 6:3 and in Lydia He Liu, The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Henrietta Harrison. China (London: Arnold; New York: Oxford University Press; Inventing the Nation Series, 2001. ISBN 0-340-74133-3), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Nevius, John (1868). China and the Chinese. Harper. pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c "清朝时期"中国"作为国家名称从传统到现代的发展". Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ 屠寄 (1907). 中國地理學教科書. 商務印書館. pp. 19–24.

- ^ Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Rev. and enl., 2000 ISBN 0-674-00247-4 ), 132.

- ^ Douglas R. Reynolds. China, 1898–1912: The Xinzheng Revolution and Japan. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1993 ISBN 0674116607), pp. 215–16 n. 20.

- ^ 黄兴涛 (2023). 重塑中华. 大象出版社. p. 48.

- ^ Lydia He. LIU; Lydia He Liu (30 June 2009). The Clash of Empires: the invention of China in modern world making. Harvard University Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-674-04029-8.

- ^ 晚清駐英使館照會檔案, Volume 1. 上海古籍出版社. 2020. p. 28. ISBN 9787532596096. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ "The Large Dragons of China". Stanley Gibbons. 7 April 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ "中國歷史教科書(原名本朝史講義)第1页". Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ Wilkinson, p. 132.

- ^ Wilkinson 2012, p. 191.

- ^ Man and the universe. Japan. Siberia. China, p710

- ^ Mission Stories of Many Lands, A Book for Young People, p174

- ^ Mesny's Chinese Miscellany, Volume 2, p3

- ^ Durant, Will (2014). The Complete Story of Civilization. Simon & Schuster. p. 631. ISBN 9781476779713.

- ^ New England Stamp Monthly, Volumes 1-2, p67

- ^ Frank B. Bessac (2006). Death on the Chang Tang - Tibet, 1950 : the Education of an Anthropologist. University of Montana Printing & Graphic Services. p. 9. ISBN 9780977341825.

- ^ Xi'an, Shaanxi Sheng, China (1994). Shaanxi Teachers University journal - Philosophy and Social sciences. 陕西师范大学. p. 91. ISBN 9780977341825.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Patricia Bjaaland Welch (2013). Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery. Tuttle Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 9781462906895.

- ^ Pialat, François (2011). 29 Chinese Mysteries. AuthorHouse UK. p. 69. ISBN 9781456789237.

- ^ 孔穎達《春秋左傳正義》:「中國有禮儀之大,故稱夏;有服章之美,謂之華。」

- ^ a b c Wang, Zhang (2014). Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14891-7.

- ^ a b c "'Celestial' origins come from long ago in Chinese history". Mail Tribune. Rosebud Media LLC. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (13 September 2013). China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-136-79141-3.

- ^ H. Mark Lai (4 May 2004). Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions. AltaMira Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7591-0458-7.

- ^ Tai, Pao-tsun (2007). The Concise History of Taiwan (Chinese-English bilingual ed.). Nantou City: Taiwan Historica. p. 52. ISBN 9789860109504.

- ^ "Entry #60161 (有唐山公,無唐山媽。)". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan]. (in Chinese and Hokkien). Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011.

- ^ Tackett, Nicolas (2017). Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-107-19677-3.

- ^ Zuikei Shuho and Charlotte von Verschuer (2002). "Japan's Foreign Relations from 1200 to 1392 A.D.: A Translation from "Zenrin Kokuhōki"". Monumenta Nipponica. 57 (4): 432.

- ^ 《中華民國教育部重編國語辭典修訂本》:「以其位居四方之中,文化美盛,故稱其地為『中華』。」

- ^ Wilkinson. Chinese History: A Manual. p. 32.

- ^ Mei Feng. "中華民國應譯為「PRC」". 开放网. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2022-05-25.2014-07-12

- ^ BBC 中文網 (2005-08-29). 論壇:台總統府網頁加注“台灣” [Forum: Adding "Taiwan" to the website of Taiwan's Presidential Office] (in Traditional Chinese). BBC 中文網. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

台總統府公共事務室陳文宗上周六(7月30日)表示,外界人士易把中華民國(Republic of China),誤認為對岸的中國,造成困擾和不便。公共事務室指出,為了明確區別,決定自周六起於中文繁體、簡體的總統府網站中,在「中華民國」之後,以括弧加注「臺灣」。[Chen Wen-tsong, Public Affairs Office of Taiwan's Presidential Office, stated last Saturday (30 July) that outsiders tend to mistake the Chung-hua Min-kuo (Republic of China) for China on the other side, causing trouble and inconvenience. The Public Affairs Office pointed out that in order to clarify the distinction, it was decided to add "Taiwan" in brackets after "Republic of China" on the website of the Presidential Palace in traditional and simplified Chinese starting from Saturday.]

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed (AHD4). Boston and New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 2000, entries china, Qin, Sino-.

- ^ Axel Schuessler (2006). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- ^ a b c Yule (2005), p. 2–3 "There are reasons however for believing the word China was bestowed at a much earlier date, for it occurs in the Laws of Manu, which assert the Chinas to be degenerate Kshatriyas, and the Mahabharat, compositions many centuries older that imperial dynasty of Ts'in ... And this name may have yet possibly been connected with the Ts'in, or some monarchy of the like title; for that Dynasty had reigned locally in Shen si from the ninth century before our era..."

- ^ a b c d e Samuel Wells Williams (2006). The Middle Kingdom: A Survey of the Geography, Government, Literature, Social Life, Arts and History of the Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-7103-1167-2.

- ^ "China". Oxford English Dictionary (1989). ISBN 0-19-957315-8.

- ^ Barbosa, Duarte; Dames, Mansel Longworth (1989). ""The Very Great Kingdom of China"". The Book of Duarte Barbosa. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0451-2. Archived from the original on 2023-04-11. Retrieved 2020-11-18. In the Portuguese original Archived 2013-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, the chapter is titled "O Grande Reino da China".

- ^ Eden, Richard (1555). Decades of the New World: "The great China whose kyng is thought the greatest prince in the world."

Myers, Henry Allen (1984). Western Views of China and the Far East, Volume 1. Asian Research Service. p. 34. - ^ Wade (2009), pp. 8–11

- ^ Berthold Laufer (1912). "The Name China". T'oung Pao. 13 (1): 719–726. doi:10.1163/156853212X00377.

- ^ "China". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2020-03-14. Retrieved 2020-01-21.ISBN 0-19-957315-8

- ^ Yule (2005), p. 3–7

- ^ a b Wade (2009), pp. 12–13

- ^ Bodde, Derk (26 December 1986). Denis Twitchett; Michael Loewe (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC – AD 220. Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ a b Wade (2009), p. 20

- ^ Liu, Lydia He, The clash of empires, p. 77. ISBN 9780674019959. "Scholars have dated the earliest mentions of Cīna to the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata and to other Sanskrit sources such as the Hindu Laws of Manu."

- ^ Wade (2009) "This thesis also helps explain the existence of Cīna in the Indic Laws of Manu and the Mahabharata, likely dating well before Qin Shihuangdi."

- ^ "Sino-". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2015-07-14. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- ^ a b Yule (2005), p. xxxvii

- ^ Yule (2005), p. xl

- ^ Stefan Faller (2011). "The World According to Cosmas Indicopleustes – Concepts and Illustrations of an Alexandrian Merchant and Monk". Transcultural Studies. 1 (2011): 193–232. doi:10.11588/ts.2011.1.6127. Archived from the original on 2015-07-14. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- ^ William Smith; John Mee Fuller, eds. (1893). Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible. p. 1328.

- ^ John Kitto, ed. (1845). A cyclopædia of biblical literature. p. 773.

- ^ William Smith; John Mee Fuller, eds. (1893). Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible. p. 1323.

- ^ Sinor, D. (1998), "Chapter 11 – The Kitan and the Kara Kitay", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C. E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, vol. 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- ^ a b James A. Millward; Peter C. Perdue (2004). S.F.Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-317-45137-2.

- ^ Rui, Chuanming (2021). On the Ancient History of the Silk Road. World Scientific. doi:10.1142/9789811232978_0005. ISBN 978-981-12-3296-1.

- ^ Victor Mair (May 16, 2022). "Tuoba and Xianbei: Turkic and Mongolic elements of the medieval and contemporary Sinitic states". Language Log. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ 习近平 (2019-09-27). "在全国民族团结进步表彰大会上的讲话". National Ethnic Affairs Commission of the People's Republic of China (in Chinese). Retrieved 5 April 2024.

分立如南北朝,都自诩中华正统;对峙如宋辽夏金,都被称为"桃花石";统一如秦汉、隋唐、元明清,更是"六合同风,九州共贯"。

- ^ Samuel E. Martin, Dagur Mongolian Grammar, Texts, and Lexicon, Indiana University Publications Uralic and Altaic Series, Vol. 4, 1961

- ^ Donn F. Draeger; Robert W. Smith (1980). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. Kodansha International. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6.

- ^ Yule (2005), p. 177

- ^ Tan Koon San (15 August 2014). Dynastic China: An Elementary History. The Other Press. p. 247. ISBN 9789839541885.

- ^ Yule (2005), p. 165

- ^ "Pambansang Diksyunaryo". Diksyunaryo.ph.

- ^ Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. Pedro de San Buena Ventura. 1613. p. 187.

- ^ "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary". The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Blust, Robert & Trussel, Stephen & Smith, Alexander D. & Forkel, Robert.

- ^ "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary". The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Blust, Robert & Trussel, Stephen & Smith, Alexander D. & Forkel, Robert.

- ^ 唐, 淑芬; 杨, 洋, eds. (2006). "VII、邮政". 中国手语日常会话 (in Chinese). 北京: 华夏出版社. p. 88. ISBN 9787508038247.

- ^ "China". ASL Sign Language Dictionary. Princeton University. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Bailey, Carole Sue; Dolby, Kathy, eds. (27 June 2002). "Geographic Place Names". The Canadian Dictionary of ASL. Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press, The Canadian Cultural Society of the Deaf. p. lxxx. ISBN 0-88864-300-4. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Vicars, William G. "CHINA". American Sign Language University. Sacramento, California. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Tennant, Richard A.; Gluszak Brown, Marianne (1998). The American Sign Language Handshape Dictionary (1st ed.). Washington, DC: Clerc Books, Gallaudet University Press. pp. 126, 311. ISBN 978-1-56368-043-4. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "🇺🇸 China 🇪🇪 Hiina". Spread the Sign. European Sign Language Center. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "🇺🇸 China 🇫🇷 Chine". Spread the Sign. European Sign Language Center. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ מנשה, דבי (22 August 2020). "ארצות / מדינות העולם בשפת הסימנים הישראלית". YouTube (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "🇺🇸 China". Spread the Sign. European Sign Language Center. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "China 中國". LSD Visual Sign Language Dictionary. Sign Assisted Instruction Programme.

- ^ "Mainland China". TSL Online Dictionary. The Taiwan Center for Sign Linguistics, National Chung Cheng University. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Cassel, Par Kristoffer (2011). Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979212-2. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dvořák, Rudolf (1895). Chinas religionen ... (in German). Vol. 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Aschendorff (Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung). ISBN 0-19-979205-4. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-36222-6. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4684-2. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Hauer, Erich (2007). Corff, Oliver (ed.). Handwörterbuch der Mandschusprache (in German). Vol. 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05528-4. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Esherick, Joseph (2006). "How the Qing Became China". Empire to Nation: Historical Perspectives on the Making of the Modern World. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wade, Geoff (May 2009). "The Polity of Yelang and the Origin of the Name 'China'" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 188. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute