Alister Hardy

Sir Alister Hardy FRS | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alister Clavering Hardy 10 February 1896 Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Died | 22 May 1985 (aged 89) Oxford, Oxfordshire, England |

| Known for | RRS Discovery work Continuous Plankton Recorder Aquatic ape hypothesis |

| Spouse | Sylvia Garstang |

| Parent(s) | Richard Hardy and Elizabeth Hannah Clavering |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society, Templeton Prize |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Marine zoology |

| Institutions | University of Hull, University of Aberdeen, University of Oxford |

Sir Alister Clavering Hardy FRS FRSE FLS[1] (10 February 1896 – 22 May 1985) was an English marine biologist, an expert on marine ecosystems spanning organisms from zooplankton to whales. He had the artistic skill to illustrate his books with his own drawings, maps, diagrams, and paintings.

Hardy served as zoologist on the RRS Discovery's voyage to explore the Antarctic between 1925 and 1927. On the voyage he invented the Continuous Plankton Recorder; it enabled any ship to collect plankton samples during an ordinary voyage.

After retiring from his academic work, Hardy founded the Religious Experience Research Centre in 1969; he won the Templeton Prize for this in 1985.

Camoufleur and artist

[edit]

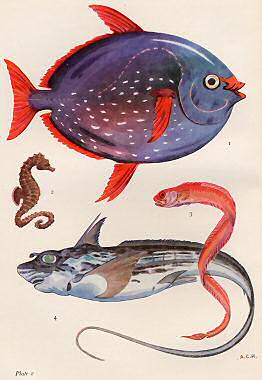

Rare and Unusual Fish in British Waters.

- Opah, Lampris guttatus

- Sea Horse, Hippocampus europaeus

- Red Bandfish, Cepola rubescens

- Rabbit-fish, Chimaera monstrosa

Hardy was born in Nottingham, the son of Richard Hardy, an architect, and his wife, Elizabeth Hannah Clavering.[2] He was educated not far away at Oundle School. He had intended to go to Oxford University in 1914, but on the outbreak of war he instead volunteered for the army, and was made a camoufleur, a camouflage officer. Hardy wrote that he had been[3]

equally drawn to science and art, and if the truth be known, I must confess that it is the latter that has the greater appeal. I am lucky in not having been torn between the two; I have managed to combine them.[3]

He was selected for camouflage work by the artist Solomon J. Solomon, who apparently mistook him for a different Hardy who was a professional artist.[4] Hardy however did have sufficient artistic skill to serve his military and scientific work. He illustrated his New Naturalist books with his own line drawings, maps, diagrams, photographs, and paintings.[5] For example, plate 2 of Fish and Fisheries illustrates the depicted "Rare and Unusual Fish in British Waters" both accurately and vividly. Hardy described the camoufleurs as including artists and "scientists with artistic inclinations", himself perhaps among them.[4]

In later life, Hardy travelled in India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Cambodia, China and Japan, recording his visits to temples in all those countries in watercolour paintings. Many of these are in the University of Wales Trinity Saint David collection.[6]

Zoology

[edit]

Hardy was the zoologist on the RRS Discovery voyage to explore the Antarctic between 1925 and 1927, as part of the Discovery Investigations. Through his studies of zooplankton and its relationship with predators, he became expert in marine mammals such as whales. Whilst on board the Discovery he designed and later built a mechanism called the Continuous Plankton Recorder or CPR. The CPR collects plankton samples and stores them on a moving band of silk, preserving them in formalin. His pioneering research into plankton distribution and abundance is continued by the Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey (CPR Survey).

Hardy was the first Professor of Zoology at the University of Hull from 1928 – 1942. In 1942, he was then appointed Professor of Natural History at the University of Aberdeen, where he remained until 1946, when he became Linacre Professor of Zoology in the University of Oxford and Fellow of Merton College, a position he held until 1963.[7] In 1940, Hardy was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.[1] He was knighted in 1957.

Evolution

[edit]Hardy identified as a Darwinian, he denied the Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics. He was a proponent of organic selection (also known as the Baldwin effect). He held the view that behavioral changes can be important for evolution.[8][9]

Aquatic ape hypothesis

[edit]In 1930, while reading Wood Jones' Man's Place among the Mammals, which included the question of why humans, unlike all other land mammals, had fat attached to their skin, Hardy realized that this trait sounded like the blubber of marine mammals, and began to suspect that humans had ancestors that were more aquatic than previously imagined. Fearing a backlash against such a radical idea, he kept this hypothesis secret until 1960, when he spoke and later wrote on the subject, which subsequently became known as the aquatic ape hypothesis in academic circles,[10] and has been promoted in particular by Elaine Morgan, who acknowledged her debt to Hardy in her book The Scars of Evolution,[11] and elsewhere.[12]

Study of religion

[edit]Dating from his boyhood at Oundle School, Hardy had a lifelong interest in spiritual phenomena, but aware that his interests were likely to be considered unorthodox in the scientific community, apart from occasional lectures he kept his opinions to himself until his retirement from his Oxford Chair. During the academic sessions of 1963–4 and 1964–5, he gave the Gifford Lectures at Aberdeen University on 'Evolution and the spirit of Man', later published as The Living Stream and The Divine Flame. These lectures signalled his wholehearted return to his religious interests. In 1969 he founded the Religious Experience Research Unit in Manchester College, Oxford. The Unit began its work by compiling a database of religious experiences and continues to investigate the nature and function of spiritual and religious experience at the University of Wales, Lampeter. In 1973 he met with A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and other devotees of the Hare Krishna movement and discussed Vedic literature, the divine flame and Rabindranath Tagore.[13]

Hardy's biological approach to the roots of religion is non-reductionist, seeing religious awareness as having evolved in response to a genuine dimension of reality.[14] For his work in founding the Religious Experience Research Centre, Hardy received the Templeton Prize shortly before his death in 1985.[15]

Family

[edit]He was married to Sylvia Garstang in 1927.[16]

Works

[edit]Hardy wrote numerous scientific papers on plankton, fish and whales. He wrote two popular books in the New Naturalist series, and in later life he also wrote on religion.

- Books

- The Open Sea. Its Natural History (Part I) The World of Plankton. New Naturalist No. 34, Collins, 1956.

- The Open Sea. Its Natural History (Part II) Fish & Fisheries. New Naturalist No. 37, Collins, 1959.

- The Living Stream: Evolution and Man. New York and Evanston: Harper & Row, Publishers. 1965 – via Internet Archive.

- The Divine Flame: An Essay Towards A Natural History of Religion. Collins, 1966.

- The Spiritual Nature of Man: Study of Contemporary Religious Experience. Oxford University Press, 1979.

- Papers

- The Herring in Relation to its Animate Environment. Fish. Invest. Lond., II, 7:3. 1951.

- (with E.R. Gunther) The Plankton of the South Georgia Whaling Grounds and Adjacent Waters, 1926-7. 'Discovery' Report, II, 1–146.

Recognition

[edit]Hardy's "pioneering work" was recognised by South Georgia & South Sandwich Islands in 2011 with a set of four commemorative stamps bearing his image.[17]

The University of Hull has named a building on its Hull Campus after Hardy.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Marshall, N. B. (1986). "Alister Clavering Hardy. 10 February 1896-22 May 1985". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 32: 222–226. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1986.0008.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ a b Behrens, Roy R (February 2009). "Revisiting Abbott Thayer: non-scientific reflections about camouflage in art, war and zoology". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 364 (1516): 497–501. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0250. PMC 2674083. PMID 19000975.

- ^ a b Forbes, Peter. Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage. Yale, 2009. p. 101.

- ^ Hardy, The Open Sea, 1956 and 1959.

- ^ Schmidt, Bettina (2012). "Sir Alister Hardy's Art". The Alister Hardy Society. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 353.

- ^ Wyles J. S., Kunkel J. G., Wilson A. C., (1983). Birds, Behavior and Anatomical Evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80: 4394–4397.

- ^ Burkhardt, Richard W. (2013). Lamarck, Evolution, and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters. Genetics 194: 793–805.

- ^ Hardy, Alister Clavering (1977). "Was there a Homo aquaticus?". Zenith. 15 (1): 4–6.

- ^ Morgan, Elaine (1994). The Scars of Evolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195094312.

- ^ Morgan, E (2002). "Was man more aquatic in the past. What happens when you change the paradigm?". Nutrition and Health. 16 (1): 23–24. doi:10.1177/026010600201600106. PMID 12083406. S2CID 39428800.

- ^ Prabhupada, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami. "Discussion with Alister Hardy". prabhupadavani.org. Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ Hay, David (2006). Something There: The Biology of the Human Spirit. London: Darton, Longman & Todd.[page needed]

- ^ Hood, Ralph Jr. (2003). The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-57230-116-0.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Stamps Issues: SGSSI Recognize the Pioneering Work of Sir Alister Hardy Archived 25 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. 19 March 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- David Hay, God’s Biologist: A life of Alister Hardy (London, Darton Longman and Todd, 2011).

External links

[edit]- 1896 births

- 1985 deaths

- Military personnel from Nottingham

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British Army officers

- English marine biologists

- Fellows of Exeter College, Oxford

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- Fellows of Merton College, Oxford

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Scientists from Nottingham

- Templeton Prize laureates

- Academics of the University of Aberdeen

- Academics of the University of Hull

- Knights Bachelor

- Linacre Professors of Zoology

- British parapsychologists

- Camoufleurs

- 20th-century English writers

- New Naturalist writers

- 20th-century English zoologists

- People educated at Oundle School