Courtauld Gallery

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

| |

Interior of the Courtauld Gallery | |

| Established | 1932 |

|---|---|

| Location | Somerset House, Strand London, WC2 England |

| Coordinates | 51°30′42.3″N 0°07′02.9″W / 51.511750°N 0.117472°W |

| Type | Art collection |

| Collection size | 530 paintings; 26,000 drawings |

| Director | Ernst Vegelin |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | courtauld |

The Courtauld Gallery (UK: /ˈkɔːrtoʊld/) is an art museum in Somerset House, on the Strand in central London. It houses the collection of the Samuel Courtauld Trust and operates as an integral part of the Courtauld Institute of Art.

The Courtauld collection was formed largely through donations and bequests, and includes paintings, drawings, sculptures and other works from medieval to modern times. It is particularly known for its French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. The collection contains some 530 paintings and over 26,000 drawings and prints.[1] The head of the Courtauld Gallery is Ernst Vegelin.[2] The gallery closed on 3 September 2018 for a major redevelopment, called Courtauld Connects,[3][4] and reopened on 19 November 2021.[5]

The Courtauld Institute of Art is a self-governing college of the University of London specialising in the study of the history of art. The director designate of the Courtauld Institute of Art is Professor Mark Hallett.

History

[edit]

The Courtauld Institute was founded in 1932 through the philanthropic efforts of the industrialist and art collector Samuel Courtauld, the diplomat and collector Lord Lee of Fareham, and the art historian Sir Robert Witt.

The art collection at the Courtauld was begun by Samuel Courtauld, who in the same year presented an extensive collection of paintings, mainly French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works. He made further gifts later in the 1930s and a bequest in 1948.

His collection included Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère and a version of the Déjeuner sur l'Herbe, Renoir's La Loge, landscapes by Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, a ballet scene by Edgar Degas, and a group of eight major works by Cézanne. Other paintings include Vincent van Gogh's Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Peach Blossoms in the Crau, Gauguin's Nevermore and Te Rerioa, and important works by Seurat, Henri "le Douanier" Rousseau, Toulouse-Lautrec and Modigliani.

Further bequests were added after the Second World War, most notably the collection of Old Master paintings assembled by Lord Lee, a founder of the institute. This included Cranach's Adam and Eve and a sketch in oils by Peter Paul Rubens for what is arguably his masterpiece, the Deposition altarpiece in Antwerp Cathedral.

Sir Robert Witt, also a founder of the Courtauld Institute, was an outstanding benefactor and bequeathed his important collection of Old Master and British drawings in 1952. His bequest included 20,000 prints and more than 3000 drawings. His son, Sir John Witt, later gave more English watercolours and drawings to the Gallery.

In 1958, Pamela Diamand, the daughter of Roger Fry the art critic and founder of the Omega Workshops, donated his collection of 20th-century art including works by Bloomsbury Group artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

In 1966, Mark Gambier-Parry, son of Major Ernest Gambier-Parry, bequeathed the diverse collection of art formed by his grandfather, Thomas Gambier Parry, which ranged from Early Italian Renaissance painting to majolica, medieval enamel and ivory carvings, and other types of art (see section below).

Dr William Wycliffe Spooner (1882–1967) and his wife Mercie added to the Gallery's collection of English watercolours in 1967 with a bequest of works by John Constable, John Sell Cotman, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, Thomas Gainsborough, Thomas Girtin, Samuel Palmer, Thomas Rowlandson, Paul Sandby, Francis Towne, J. M. W. Turner, Peter De Wint and others.[1][6]

In 1974, a group of thirteen watercolours by Turner was presented in memory of Sir Stephen Courtauld, who restored Eltham Palace, and the brother of Samuel Courtauld.

In 1978 the Courtauld received the Princes Gate Collection of Old Master paintings and drawings formed by Count Antoine Seilern. The collection rivals the Samuel Courtauld Collection in importance. It includes paintings by Bernardo Daddi, Robert Campin, Bruegel, Quentin Matsys, Van Dyck and Tiepolo, but is strongest in the works of Rubens. The bequest also included a group of 19th- and 20th‑century works by Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Oskar Kokoschka.

The art dealer and art historian Lillian Browse donated more than thirty works in 1982, and bequeathed a further eight; among them were bronzes by Degas and Rodin, and paintings by William Nicholson and Walter Sickert.[7]

A collection of more than 50 British watercolours, including eight by Turner, was left to the Gallery by Dorothy Scharf in 2004.[8]

The gallery closed on 3 September 2018 until 19 November 2021 for a major redevelopment costing £50M.[4]

Location

[edit]

From 1958 to 1989 the Courtauld collection was housed in part of the premises of the Warburg Institute in Woburn Square;[9] it was thus separated from the Courtauld Institute, which was in Home House, Portman Square.

Since 1989 it has been housed, together with the Courtauld Institute, in the North or Strand block of Somerset House, in the rooms designed and purpose-built by Sir William Chambers for the learned societies, namely the Royal Academy (of which Chambers was the first Treasurer), the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries.

The Royal Academy occupied them from their completion in 1780 until it moved to the new National Gallery building in Trafalgar Square in 1837. Inscribed over the entrance to the Great Room, in which the annual Royal Academy summer exhibition was held, is the formidable inscription ΟΥΔΕΙΣ ΑΜΟΥΣΟΣ ΕΙΣΙΤΩ ("Let no stranger to the Muses enter" in Ancient Greek).[10]

Highlights of the collection

[edit]Paintings

[edit]

Dutch School

- Vincent van Gogh – 3 paintings;

Early Netherlandish

- Robert Campin (or Master of Flemalle), the Seilern Triptych

- Quentin Matsys – 2 paintings;

English School

- William Beechey – 2 paintings;

- Thomas Gainsborough – 2 paintings;

- Peter Lely – 3 paintings;

Flemish School

- Anthony van Dyck – 5 paintings;

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder – 2 paintings, many drawings;

- Peter Paul Rubens – 29 paintings;

- David Teniers the Younger – 10 paintings;

French School

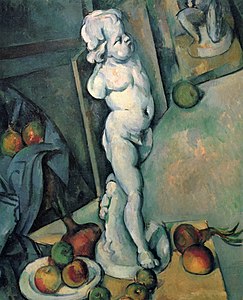

- Paul Cézanne – 12 paintings;

- Edgar Degas – 6 paintings;

- Paul Gauguin – 3 paintings;

- Claude Lorrain – 1 painting;

- Édouard Manet – 4 paintings;

- Claude Monet – 3 paintings;

- Camille Pissarro – 4 paintings;

- Alfred Sisley – 2 paintings;

- Georges-Pierre Seurat – 9 paintings;

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir – 4 paintings;

- Chaïm Soutine – 1 painting;

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – 2 paintings;

- Henri Rousseau – 1 painting;

German School

- Lucas Cranach the Elder – 1 painting;

Italian School

- Fra Angelico – 4 paintings;

- Giovanni Bellini – 1 painting;

- Sandro Botticelli – 1 painting;

- Bernardo Daddi – 2 paintings;

- Lorenzo Lotto – 2 paintings;

- Lorenzo Monaco – 2 paintings;

- Pietro Perugino – 1 painting;

- Pesellino – a diptych

- Parmigianino – 2 paintings;

- Giovanni Battista Tiepolo – 12 paintings;

- Tintoretto – 2 paintings;

Spanish School

- Francisco Goya – 1 painting;

Gambier-Parry Collection

[edit]

Thomas Gambier Parry (1816–1888) was a keen and versatile collector for most of his adult life. Many of his purchases were made on trips to the continent, especially Italy, but he also bought from dealers and auctions in England, and sometimes sold items.

His most important collections were of late medieval and Early Renaissance paintings, small sculpted reliefs, ivories, and maiolica, but he also had a significant early collection of Islamic metalwork, and a variety of other types of objects, for example Hispano-Moresque ware, glass and three small post-Byzantine wooden crosses from Mount Athos elaborately carved with miniature scenes.

The Courtauld Gallery website shows images and descriptions of 324 objects from the 1966 bequest, which included the bulk of the collection.[11]

Gambier Parry began by collecting mostly 16th- and 17th-century works, but his focus gradually moved to 14th- and 15th-century works, still relatively little collected, although Prince Albert was among British collectors of "Italian Primitives", as Trecento paintings were then known. Among his most important paintings were a Coronation of the Virgin by Lorenzo Monaco, one of the larger works in the collection, three predella panels with roundels of Christ and saints by Fra Angelico, and a small but important diptych of the Annunciation by Pesellino. There are two further predella panels by Lorenzo Monaco, and many other small panels by lesser-known masters. Later Renaissance works include ones by Il Garofalo, Sassoferrato, and there is a Baroque Assumption by Francesco Solimena. There are a number of illuminated manuscript pages from the workshop of the Boucicaut Master.

The sculptures include three fine 15th-century marble reliefs of the Virgin and Child, the most significant by Mino da Fiesole.[12] There is a Limoges enamel book cover panel, a number of Renaissance Limoges items, and several small Gothic ivories.[12][13][14]

Gallery

[edit]-

Robert Campin, Seilern Triptych, c. 1425

-

Parmigianino, Virgin and Child, 1525–1527

-

Peter Paul Rubens, The Family of Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1613-1615

-

Thomas Gainsborough, Portrait of Margaret Gainsborough, 1778

-

Édouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass, c. 1863-1868

-

Claude Monet, Autumn Effect at Argenteuil, 1873

-

Edgar Degas, Two Dancers on a Stage, 1874

-

Edgar Degas, Woman at a Window, 1875–1878

-

Georges Seurat, Bridge of Courbevoie, 1886–1887

-

Vincent van Gogh, Peach Trees in Blossom, April, 1889

-

Georges Seurat, Young Woman Powdering Herself, 1889–1890

-

Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1892–1895

-

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Cherub, 1895

-

Paul Gauguin, Nevermore (O Taiti), 1897

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1908

-

Amedeo Modigliani, Female Nude, 1916

Resources

[edit]The Courtauld publishes an online image collection, artandarchitecture.org.uk,[15] which provides access to more than 40,000 images, including paintings and drawings from The Courtauld Gallery, and over 35,000 photographs of architecture and sculpture from the Conway Library of the institute. The site was developed with the support of the New Opportunities Fund.

Two other websites courtauldimages.com[16] and courtauldprints.com[17] sell high resolution digital files to scholars, publishers and broadcasters, and photographic prints to the general public.

References

[edit]- ^ a b John Murdoch (1998). The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 7.

- ^ Dr Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen. The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2013. Accessed April 2013. Archived here.

- ^ "After the National Gallery, the Courtauld is the latest London institution to send masterpieces to Japan". theartnewspaper.com. 25 July 2019.

- ^ a b correspondent, Mark Brown Arts (23 November 2017). "Courtauld Gallery to close for two years for £50m revamp". The Guardian.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "About the Courtauld Gallery". Courtauld Gallery. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Michael Broughton; William Clarke; Joanna Selborne (2005). The Spooner Collection of British watercolours at the Courtauld Institute Gallery, exhibition catalogue. [London]: Courtauld Institute of Art. ISBN 9781870787963.

- ^ Dennis Farr (2006). Empathy for Art and Artists: Lillian Browse, 1906–2005. Newsletter of the Courtauld Institute of Art, Issue 21: Spring 2006. Archived 7 October 2013.

- ^ The Collection: Drawings and Prints: the collectors. Courtauld Institute of Art, 2012. Accessed April 2013.

- ^ About Us: A Short History of the Courtauld. The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2011. Accessed April 2013.

- ^ Farr, Dennis; Newman, John (1990). Guide to the Courtauld Institute Galleries at Somerset House. London: Courtauld Institute Galleries. p. 36.

- ^ Search for "Gambier Parry" on A&A – art and architecture. The Courtauld Institute of Art. Accessed June 2013.

- ^ a b John Pope-Hennessy (March 1967). "Three Marble Reliefs in the Gambier-Parry Collection". The Burlington Magazine, The Gambier-Parry Bequest to The University of London. 109(768): 117-121+123. (subscription required).

- ^ Anthony Blunt (March 1967). "The History of Thomas Gambier Parry's Collection". The Burlington Magazine, The Gambier-Parry Bequest to The University of London. 109(768): 112-116+119+135+141+145-146+150+153+159-160+167+171. (subscription required).

- ^ John Valentine Granville Mallet (March 1967). "Italian Maiolica in the Gambier-Parry Collection". The Burlington Magazine, The Gambier-Parry Bequest to The University of London. 109(768): 144–151. (subscription required).

- ^ Art and architecture. The Courtauld Institute of Art. Accessed April 2013.

- ^ Courtauld Images. The Courtauld Institute of Art. Accessed April 2013.

- ^ Courtauld Prints. Courtauld Gallery of Art. Accessed April 2013.