Traditional Chinese medicine: Difference between revisions

→Drug research: Simplified per WP:ASSERT. |

Mallexikon (talk | contribs) deleting material not supported by its source. Pls see talk page |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

TCM's view of the body places little emphasis on anatomical structures, but is mainly concerned with the identification of functional entities (which regulate digestion, breathing, aging etc.). While health is perceived as harmonious interaction of these entities and the outside world, disease is interpreted as a disharmony in interaction. TCM diagnosis aims to trace symptoms to [[Traditional Chinese medicine#Patterns|patterns]] of an underlying disharmony, by measuring the pulse, inspecting the tongue, skin, and eyes, and looking at the eating and sleeping habits of the person as well as many other things. |

TCM's view of the body places little emphasis on anatomical structures, but is mainly concerned with the identification of functional entities (which regulate digestion, breathing, aging etc.). While health is perceived as harmonious interaction of these entities and the outside world, disease is interpreted as a disharmony in interaction. TCM diagnosis aims to trace symptoms to [[Traditional Chinese medicine#Patterns|patterns]] of an underlying disharmony, by measuring the pulse, inspecting the tongue, skin, and eyes, and looking at the eating and sleeping habits of the person as well as many other things. |

||

In traditional Chinese herbal medicine, plant elements are by far the most commonly, but not solely, used substances; animal, human, and mineral products are also utilized. The effectiveness of this medical system remains poorly documented.<ref name="Shang-2007"/> There are concerns over a number of potentially toxic Chinese medicinals that consist of plants, animal parts, and minerals.<ref name="Shaw-2012"/> There is a lack of existing [[cost-effectiveness]] research for TCM.<ref name="Zhang-2012"/> Poachers hunt restricted or [[endangered species]] animals to supply the [[black market]] with TCM products.<ref name="Weirum"/><ref name="Newscientist.com"/> With an eye to the Chinese market, pharmaceutical companies have explored the potential for creating new drugs from traditional remedies.<ref name=swallow/> Successful results have however been scarce: [[artemisinin]], for example, which is an effective treatment for [[malaria]], was fished out of a herb traditionally used to treat fever.<ref name=swallow/> |

In traditional Chinese herbal medicine, plant elements are by far the most commonly, but not solely, used substances; animal, human, and mineral products are also utilized. The effectiveness of this medical system remains poorly documented.<ref name="Shang-2007"/> There are concerns over a number of potentially toxic Chinese medicinals that consist of plants, animal parts, and minerals.<ref name="Shaw-2012"/> There is a lack of existing [[cost-effectiveness]] research for TCM.<ref name="Zhang-2012"/> Poachers hunt restricted or [[endangered species]] animals to supply the [[black market]] with TCM products.<ref name="Weirum"/><ref name="Newscientist.com"/> With an eye to the Chinese market, pharmaceutical companies have explored the potential for creating new drugs from traditional remedies.<ref name=swallow/> Successful results have however been scarce: [[artemisinin]], for example, which is an effective treatment for [[malaria]], was fished out of a herb traditionally used to treat fever.<ref name=swallow/> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 01:17, 29 April 2014

Template:Contains Chinese text

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM; simplified Chinese: 中医; traditional Chinese: 中醫; pinyin: zhōng yī; lit. 'Chinese medicine') is a broad range of medicine practices sharing common concepts which have been developed in China and are based on a tradition of more than 2,000 years, including various forms of herbal medicine, acupuncture, massage (Tui na), exercise (qigong), and dietary therapy.[1]

The doctrines of Chinese medicine are rooted in books such as the Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon and the Treatise on Cold Damage, as well as in cosmological notions such as yin-yang and the five phases. Starting in the 1950s, these precepts were standardized in the People's Republic of China, including attempts to integrate them with modern notions of anatomy and pathology. Nonetheless, the bulk of these precepts, including the model of the body, or concept of disease, are not supported by science or evidence-based medicine. TCM is not based upon the current body of knowledge related to health care in accordance with the scientific community.[2]

TCM's view of the body places little emphasis on anatomical structures, but is mainly concerned with the identification of functional entities (which regulate digestion, breathing, aging etc.). While health is perceived as harmonious interaction of these entities and the outside world, disease is interpreted as a disharmony in interaction. TCM diagnosis aims to trace symptoms to patterns of an underlying disharmony, by measuring the pulse, inspecting the tongue, skin, and eyes, and looking at the eating and sleeping habits of the person as well as many other things.

In traditional Chinese herbal medicine, plant elements are by far the most commonly, but not solely, used substances; animal, human, and mineral products are also utilized. The effectiveness of this medical system remains poorly documented.[3] There are concerns over a number of potentially toxic Chinese medicinals that consist of plants, animal parts, and minerals.[4] There is a lack of existing cost-effectiveness research for TCM.[5] Poachers hunt restricted or endangered species animals to supply the black market with TCM products.[6][7] With an eye to the Chinese market, pharmaceutical companies have explored the potential for creating new drugs from traditional remedies.[8] Successful results have however been scarce: artemisinin, for example, which is an effective treatment for malaria, was fished out of a herb traditionally used to treat fever.[8]

History

Traces of therapeutic activities in China date from the Shang dynasty (14th–11th centuries BCE).[9] Though the Shang did not have a concept of "medicine" as distinct from other fields,[9] their oracular inscriptions on bones and tortoise shells refer to illnesses that affected the Shang royal family: eye disorders, toothaches, bloated abdomen, etc.,[9][10] which Shang elites usually attributed to curses sent by their ancestors.[9] There is no evidence that the Shang nobility used herbal remedies.[9] According to a 2006 overview, the "Documentation of Chinese materia medica (CMM) dates back to around 1,100 BC when only dozens of drugs were first described. By the end of the 16th century, the number of drugs documented had reached close to 1,900. And by the end of the last century, published records of CMM have reached 12,800 drugs."[11]

Stone and bone needles found in ancient tombs led Joseph Needham to speculate that acupuncture might have been carried out in the Shang dynasty.[12][13] But most historians now make a distinction between medical lancing (or bloodletting) and acupuncture in the narrower sense of using metal needles to treat illnesses by stimulating specific points along circulation channels ("meridians") in accordance with theories related to the circulation of Qi.[12][13][14] The earliest public evidence for acupuncture in this sense dates to the second or first century BCE.[9][12][13][15]

The Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon, the oldest received work of Chinese medical theory, was compiled around the first century BCE on the basis of shorter texts from different medical lineages.[12][13][16] Written in the form of dialogues between the legendary Yellow Emperor and his ministers, it offers explanations on the relation between humans, their environment, and the cosmos, on the contents of the body, on human vitality and pathology, on the symptoms of illness, and on how to make diagnostic and therapeutic decisions in light of all these factors.[16] Unlike earlier texts like Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments, which was excavated in the 1970s from a tomb that had been sealed in 168 BCE, the Inner Canon rejected the influence of spirits and the use of magic.[13] It was also one of the first books in which the cosmological doctrines of Yinyang and the Five Phases were brought to a mature synthesis.[16]

The Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and Miscellaneous Illnesses was collated by Zhang Zhongjing sometime between 196 and 220 CE, at the end of the Han dynasty. Focusing on drug prescriptions rather than acupuncture,[17][18] it was the first medical work to combine Yinyang and the Five Phases with drug therapy.[9] This formulary was also the earliest public Chinese medical text to group symptoms into clinically useful "patterns" (zheng 證) that could serve as targets for therapy. Having gone through numerous changes over time, the formulary now circulates as two distinct books: the Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and the Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Casket, which were edited separately in the eleventh century, under the Song dynasty.[19]

In the centuries that followed the completion of the Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon, several shorter books tried to summarize or systematize its contents. The Canon of Problems (probably second century CE) tried to reconcile divergent doctrines from the Inner Canon and developed a complete medical system centered on needling therapy.[17] The AB Canon of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Zhenjiu jiayi jing 針灸甲乙經, compiled by Huangfu Mi sometime between 256 and 282 CE) assembled a consistent body of doctrines concerning acupuncture;[17] whereas the Canon of the Pulse (Maijing 脈經; ca. 280) presented itself as a "comprehensive handbook of diagnostics and therapy."[17]

In 1950, Chairman Mao Zedong made a speech in support of traditional Chinese medicine which was influenced by political necessity.[20] In 1952, the president of the Chinese Medical Association said that, "This One Medicine, will possess a basis in modern natural sciences, will have absorbed the ancient and the new, the Chinese and the foreign, all medical achievements—and will be China’s New Medicine!"[20]

Historical physicians

These include Zhang Zhongjing, Hua Tuo, Sun Simiao, Tao Hongjing, Zhang Jiegu, and Li Shizhen.

Philosophical background

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is based on Yinyangism (i.e., the combination of Five Phases theory with Yin-yang theory),[21] which was later absorbed by Daoism.[22]

Yin and yang

Yin and yang are ancient Chinese concepts which can be traced back to the Shang dynasty[23] (1600–1100 BC). They represent two abstract[23] and complementary aspects that every phenomenon in the universe can be divided into.[23] Primordial analogies for these aspects are the sun-facing (yang) and the shady (yin) side of a hill.[18] Two other commonly used representational allegories of yin and yang are water and fire.[23] In the yin-yang theory, detailed attributions are made regarding the yin or yang character of things:

| Phenomenon | Yin | Yang |

|---|---|---|

| Celestial bodies[18] | moon | sun |

| Gender[18] | female | male |

| Location[18] | inside | outside |

| Temperature[18] | cold | hot |

| Direction[24] | downward | upward |

| Degree of humidity | damp/moist | dry |

The concept of yin and yang is also applicable to the human body; for example, the upper part of the body and the back are assigned to yang, while the lower part of the body are believed to have the yin character.[24] Yin and yang characterization also extends to the various body functions, and – more importantly – to disease symptoms (e.g., cold and heat sensations are assumed to be yin and yang symptoms, respectively).[24] Thus, yin and yang of the body are seen as phenomena whose lack (or overabundance) comes with characteristic symptom combinations:

- Yin vacuity (also termed "vacuity-heat"): heat sensations, possible night sweats, insomnia, dry pharynx, dry mouth, dark urine, a red tongue with scant fur, and a "fine" and rapid pulse.[25]

- Yang vacuity ("vacuity-cold"): aversion to cold, cold limbs, bright white complexion, long voidings of clear urine, diarrhea, pale and enlarged tongue, and a slightly weak, slow and fine pulse.[24]

TCM also identifies drugs believed to treat these specific symptom combinations, i.e., to reinforce yin and yang.[18]

Five Phases theory

Five Phases (五行, pinyin: wǔ xíng), sometimes also translated as the "Five Elements"[18] theory, presumes that all phenomena of the universe and nature can be broken down into five elemental qualities – represented by wood (木, pinyin: mù), fire (火pinyin: huǒ), earth (土, pinyin: tǔ), metal (金, pinyin: jīn), and water (水, pinyin: shuǐ).[26] In this way, lines of correspondence can be drawn:

| Phenomenon | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction[26] | east | south | center | west | north |

| Colour[27] | green/blue | red | yellow | white | black |

| Climate[26] | wind | heat | damp | dryness | cold |

| Taste[18] | sour | bitter | sweet | acrid | salty |

| Zang Organ[28] | Liver | Heart | Spleen | Lung | Kidney |

| Fu Organ[28] | Gallbladder | Small Intestine | Stomach | Large Intestine | Bladder |

| Sense organ[27] | eye | tongue | mouth | nose | ears |

| Facial part[27] | above bridge of nose | between eyes, lower part | bridge of nose | between eyes, middle part | cheeks (below cheekbone) |

| Eye part[27] | iris | inner/outer corner of the eye | upper and lower lid | sclera | pupil |

Strict rules are identified to apply to the relationships between the Five Phases in terms of sequence, of acting on each other, of counteraction etc.[26] All these aspects of Five Phases theory constitute the basis of the zàng-fǔ concept, and thus have great influence regarding the TCM model of the body.[18] Five Phase theory is also applied in diagnosis and therapy.[18]

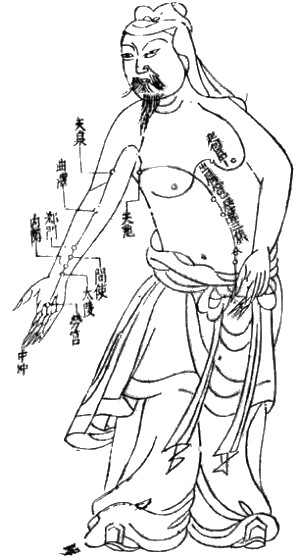

Correspondences between the body and the universe have historically not only been seen in terms of the Five Elements, but also of the "Great Numbers" (大數, pinyin: dà shū)[29] For example, the number of acu-points has at times been seen to be 365, in correspondence with the number of days in a year; and the number of main meridians – 12 – has been seen in correspondence with the number of rivers flowing through the ancient Chinese empire.[29][30]

Model of the body

TCM's view of the human body is only marginally concerned with anatomical structures, but focuses primarily on the body's functions[31][32] (such as digestion, breathing, temperature maintenance, etc.):

"The tendency of Chinese thought is to seek out dynamic functional activity rather than to look for the fixed somatic structures that perform the activities. Because of this, the Chinese have no system of anatomy comparable to that of the West."

— Ted Kaptchuk, The Web That Has No Weaver

These functions are aggregated and then associated with a primary functional entity – for instance, nourishment of the tissues and maintenance of their moisture are seen as connected functions, and the entity postulated to be responsible for these functions is xuě (blood).[32] These functional entities thus constitute concepts rather than something with biochemical or anatomical properties[33][full citation needed]

The primary functional entities used by traditional Chinese medicine are qì, xuě, the five zàng organs, the six fǔ organs, and the meridians which extend through the organ systems.[34] These are all theoretically interconnected: each zàng organ is paired with a fǔ organ, which are nourished by the blood and concentrate qi for a particular function, with meridians being extensions of those functional systems throughout the body.

Attempts to reconcile these concepts with modern science – in terms of identifying a physical correlate of them – have so far failed.[35]

Quackwatch stated that:

TCM theory and practice are not based upon the body of knowledge related to health, disease, and health care that has been widely accepted by the scientific community. TCM practitioners disagree among themselves about how to diagnose patients and which treatments should go with which diagnoses. Even if they could agree, the TCM theories are so nebulous that no amount of scientific study will enable TCM to offer rational care.[2]

Qi

TCM distinguishes several kinds of qi (simplified Chinese: 气; traditional Chinese: 氣; pinyin: qì).[36] In a general sense, qi is something that is defined by five "cardinal functions":[36][37]

- Actuation (推動, tuīdòng) – of all physical processes in the body, especially the circulation of all body fluids such as blood in their vessels. This includes actuation of the functions of the zang-fu organs and meridians.

- Warming (溫煦, pinyin: wēnxù) – the body, especially the limbs.

- Defense (防御, pinyin: fángyù) – against Exogenous Pathogenic Factors

- Containment (固攝, pinyin: gùshè) – of body fluids, i.e., keeping blood, sweat, urine, semen, etc. from leakage or excessive emission.

- Transformation (氣化, pinyin: qìhuà) – of food, drink, and breath into qi, xue (blood), and jinye (“fluids”), and/or transformation of all of the latter into each other.

Vacuity of qi will especially be characterized by pale complexion, lassitude of spirit, lack of strength, spontaneous sweating, laziness to speak, non-digestion of food, shortness of breath (especially on exertion), and a pale and enlarged tongue.[24]

Qi is believed to be partially generated from food and drink, and partially from air (by breathing).[38] Another considerable part of it is inherited from the parents and will be consumed in the course of life.[38]

TCM uses special terms for qi running inside of the blood vessels and for qi that is distributed in the skin, muscles, and tissues between those. The former is called yíng-qì (simplified Chinese: 营气; traditional Chinese: 營氣); its function is to complement xuè and its nature has a strong yin aspect (although qi in general is considered to be yang).[39] The latter is called weì-qì (Chinese: 衛氣); its main function is defence and it has pronounced yang nature.[39]

Qi also circulates in the meridians. Just as the qi held by each of the zang-fu organs, this is considered to be part of the 'principal' qi (元氣, pinyin: yuánqì) of the body[40] (also called 真氣 pinyin: zhēn qì, ‘’true‘’ qi, or 原氣 pinyin: yuán qì, ‘’original‘’ qi).[41]

Xue

In contrast to the majority of other functional entities, xuè (血, "blood") is correlated with a physical form – the red liquid running in the blood vessels.[42] Its concept is, nevertheless, defined by its functions: nourishing all parts and tissues of the body, safeguarding an adequate degree of moisture,[43] and sustaining and soothing both consciousness and sleep.[44]

Typical symptoms of a lack of xuě (usually termed "blood vacuity" [血虚, pinyin: xuě xū]) are described as: Pale-white or withered-yellow complexion, dizziness, flowery vision, palpitations, insomnia, numbness of the extremities; pale tongue; "fine" pulse.[45]

Jinye

Closely related to xuě are the jīnyė (津液, usually translated as "body fluids"), and just like xuě they are considered to be yin in nature, and defined first and foremost by the functions of nurturing and moisturizing the different structures of the body.[46] Their other functions are to harmonize yin and yang, and to help with the secretion of waste products.[47]

Jīnyė are ultimately extracted from food and drink, and constitute the raw material for the production of xuě; conversely, xuě can also be transformed into jīnyė.[48] Their palpable manifestations are all bodily fluids: tears, sputum, saliva, gastric juice, joint fluid, sweat, urine, etc.[49]

Zang-fu

The zàng-fǔ (simplified Chinese: 脏腑; traditional Chinese: 臟腑) constitute the centre piece of TCM's systematization of bodily functions. Bearing the names of organs, they are, however, only secondarily tied to (rudimentary) anatomical assumptions (the fǔ a little more, the zàng much less).[50] As they are primarily defined by their functions,[25][32] they are not equivalent to the anatomical organs – to highlight this fact, their names are usually capitalized.

The term zàng (臟) refers to the five entities considered to be yin in nature – Heart, Liver, Spleen, Lung, Kidney –, while fǔ (腑) refers to the six yang organs – Small Intestine, Large Intestine, Gallbladder, Urinary Bladder, Stomach and Sānjiaō.[51]

The zàng's essential functions consist in production and storage of qì and xuě; in a wider sense they are stipulated to regulate digestion, breathing, water metabolism, the musculoskeletal system, the skin, the sense organs, aging, emotional processes, mental activity etc.[52] The fǔ organs' main purpose is merely to transmit and digest (傳化, pinyin: chuán-huà)[53] substances like waste, food, etc.

Since their concept was developed on the basis of Wǔ Xíng philosophy, each zàng is paired with a fǔ, and each zàng-fǔ pair is assigned to one of five elemental qualities (i.e., the Five Elements or Five Phases).[54] These correspondences are stipulated as:

- Fire (火) = Heart (心, pinyin: xīn) and Small Intestine (小腸, pinyin: xiaǒcháng) (and, secondarily, Sānjiaō [三焦, "Triple Burner"] and Pericardium [心包, pinyin: xīnbaò])

- Earth (土) = Spleen (脾, pinyin: pí) and Stomach (胃, pinyin: weì)

- Metal (金) = Lung (肺, pinyin: feì) and Large Intestine (大腸, pinyin: dàcháng)

- Water (水) = Kidney (腎, pinyin: shèn) and Bladder (膀胱, pinyin: pǎngguāng)

- Wood (木) = Liver (肝, pinyin: gān) and Gallbladder (膽, pinyin: dān)

The zàng-fǔ are also connected to the twelve standard meridians – each yang meridian is attached to a fǔ organ and five of the yin meridians are attached to a zàng. As there are only five zàng but six yin meridians, the sixth is assigned to the Pericardium, a peculiar entity almost similar to the Heart zàng.[55]

Jing-luo

The meridians (经络, pinyin: jīng-luò) are believed to be channels running from the zàng-fǔ in the interior (里, pinyin: lǐ) of the body to the limbs and joints ("the surface" [表, pinyin: biaǒ]), transporting qi and xuĕ.[56][57] TCM identifies 12 "regular" and 8 "extraordinary" meridians;[34] the Chinese terms being 十二经脉 (pinyin: shí-èr jīngmài, lit. "the Twelve Vessels") and 奇经八脉 (pinyin: qí jīng bā mài) respectively.[58] There's also a number of less customary channels branching off from the "regular" meridians.[34]

Concept of disease

In general, disease is perceived as a disharmony (or imbalance) in the functions or interactions of yin, yang, qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians etc. and/or of the interaction between the human body and the environment.[24] Therapy is based on which "pattern of disharmony" can be identified.[18][59] Thus, "pattern discrimination" is the most important step in TCM diagnosis.[18][59] It is also known to be the most difficult aspect of practicing TCM.[60]

In order to determine which pattern is at hand, practitioners will examine things like the color and shape of the tongue, the relative strength of pulse-points, the smell of the breath, the quality of breathing or the sound of the voice.[61][62] For example, depending on tongue and pulse conditions, a TCM practitioner might diagnose bleeding from the mouth and nose as: "Liver fire rushes upwards and scorches the Lung, injuring the blood vessels and giving rise to reckless pouring of blood from the mouth and nose.".[63] He might then go on to prescribe treatments designed to clear heat or supplement the Lung.

Disease entities

In TCM, a disease has two aspects: "bìng" and "zhèng".[64] The former is often translated as "disease entity",[18] "disease category",[60] "illness",[64] or simply "diagnosis".[64] The latter, and more important one, is usually translated as "pattern"[18][60] (or sometimes also as "syndrome"[64]). For example, the disease entity of a common cold might present with a pattern of wind-cold in one person, and with the pattern of wind-heat in another.[18]

From a scientific point of view, most of the disease entitites (病, pinyin: bìng) listed by TCM constitute mere symptoms.[18] Examples include headache, cough, abdominal pain, constipation etc.[18]

Since therapy will not be chosen according to the disease entity but according to the pattern, two people with the same disease entity but different patterns will receive different therapy. Vice versa, people with similar patterns might receive similar therapy even if their disease entities are different. This is called 异病同治,同病异治 (pinyin: yì bìng tóng zhì, tóng bìng yì zhì,[59]"different diseases, same treatment; same disease, different treatments").

Patterns

In TCM, "pattern" (证, pinyin: zhèng) refers to a "pattern of disharmony" or "functional disturbance" within the functional entities the TCM model of the body is composed of.[18] There are disharmony patterns of qi, xuě, the body fluids, the zàng-fǔ, and the meridians.[64] They are ultimately defined by their symptoms and "signs" (i.e., for example, pulse and tongue findings).[59]

In clinical practice, the identified pattern usually involves a combination of affected entities[60] (compare with typical examples of patterns). The concrete pattern identified should account for all the symptoms a person has.[59]

Six Excesses

The Six Excesses (六淫, pinyin: liù yín,[24] sometimes also translated as "Pathogenic Factors",[65] or "Six Pernicious Influences";[32] with the alternative term of 六邪, pinyin: liù xié, – "Six Evils" or "Six Devils"[32]) are allegorical terms used to describe disharmony patterns displaying certain typical symptoms.[18] These symptoms resemble the effects of six climatic factors.[32] In the allegory, these symptoms can occur because one or more of those climatic factors (called 六气, pinyin: liù qì, "the six qi"[27]) were able to invade the body surface and to proceed to the interior.[18] This is sometimes used to draw causal relationships (i.e., prior exposure to wind/cold/etc. is identified as the cause of a disease),[27] while other authors explicitly deny a direct cause-effect relationship between weather conditions and disease,[18][32] pointing out that the Six Excesses are primarily descriptions of a certain combination of symptoms[18] translated into a pattern of disharmony.[32] It is undisputed, though, that the Six Excesses can manifest inside the body without an external cause.[18][24] In this case, they might be denoted "internal", e.g., "internal wind"[24] or "internal fire (or heat)".[24]

The Six Excesses and their characteristic clinical signs are:

- Wind (风, pinyin: fēng): rapid onset of symptoms, wandering location of symptoms, itching, nasal congestion, "floating" pulse;[27] tremor, paralysis, convulsion.[18]

- Cold (寒, pinyin: hán): cold sensations, aversion to cold, relief of symptoms by warmth, watery/clear excreta, severe pain, abdominal pain, contracture/hypertonicity of muscles, (slimy) white tongue fur, "deep"/"hidden" or "string-like" pulse,[66] or slow pulse.[32]

- Fire/Heat (火, pinyin: huǒ): aversion to heat, high fever, thirst, concentrated urine, red face, red tongue, yellow tongue fur, rapid pulse.[18] (Fire and heat are basically seen to be the same)[24]

- Dampness (湿, pinyin: shī): sensation of heaviness, sensation of fullness, symptoms of Spleen dysfunction, greasy tongue fur, "slippery" pulse.[32]

- Dryness (燥, pinyin: zào): dry cough, dry mouth, dry throat, dry lips, nosebleeds, dry skin, dry stools.[18]

- Summerheat (暑, pinyin: shǔ): either heat or mixed damp-heat symptoms.[24]

Six-Excesses-patterns can consist of only one or a combination of Excesses (e.g., wind-cold, wind-damp-heat).[27] They can also transform from one into another.[27]

Typical examples of patterns

For each of the functional entities (qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians etc.), typical disharmony patterns are recognized; for example: qi vacuity and qi stagnation in the case of qi;[24] blood vacuity, blood stasis, and blood heat in the case of xuĕ;[24] Spleen qi vacuity, Spleen yang vacuity, Spleen qi vacuity with down-bearing qi, Spleen qi vacuity with lack of blood containment, cold-damp invasion of the Spleen, damp-heat invasion of Spleen and Stomach in case of the Spleen zàng;[18] wind/cold/damp invasion in the case of the meridians.[59]

TCM gives detailed prescriptions of these patterns regarding their typical symptoms, mostly including characteristic tongue and/or pulse findings.[24][59] For example:

- "Upflaming Liver fire" (肝火上炎, pinyin: gānhuǒ shàng yán): Headache, red face, reddened eyes, dry mouth, nosebleeds, constipation, dry or hard stools, profuse menstruation, sudden tinnitus or deafness, vomiting of sour or bitter fluids, expectoration of blood, irascibility, impatience; red tongue with dry yellow fur; slippery and string-like pulse.[24]

Basic principles of pattern discrimination

The process of determining which actual pattern is on hand is called 辩证 (pinyin: biàn zhèng, usually translated as "pattern diagnosis",[18] "pattern identification"[24] or "pattern discrimination"[60]). Generally, the first and most important step in pattern diagnosis is an evaluation of the present signs and symptoms on the basis of the "Eight Principles" (八纲, pinyin: bā gāng).[18][24] These eight principles refer to four pairs of fundamental qualities of a disease: exterior/interior, heat/cold, vacuity/repletion, and yin/yang.[24] Out of these, heat/cold and vacuity/repletion have the biggest clinical importance.[24] The yin/yang quality, on the other side, has the smallest importance and is somewhat seen aside from the other three pairs, since it merely presents a general and vague conclusion regarding what other qualities are found.[24] In detail, the Eight Principles refer to the following:

- Exterior (表, pinyin: biǎo) refers to a disease manifesting in the superficial layers of the body – skin, hair, flesh, and meridians.[24] It is characterized by aversion to cold and/or wind, headache, muscle ache, mild fever, a "floating" pulse, and a normal tongue appearance.[24]

- Interior (里, pinyin: lǐ) refers to disease manifestation in the zàng-fǔ, or (in a wider sense) to any disease that can not be counted as exterior.[27] There are no generalized characteristic symptoms of interior patterns, since they'll be determined by the affected zàng or fǔ entity.[24]

- Cold (寒, pinyin: hán) is generally characterized by aversion to cold, absence of thirst, and a white tongue fur.[24] More detailed characterization depends on whether cold is coupled with vacuity or repletion.[24]

- Heat (热, pinyin: rè) is characterized by absence of aversion to cold, a red and painful throat, a dry tongue fur and a rapid and floating pulse, if it falls together with an exterior pattern.[24] In all other cases, symptoms depend on whether heat is coupled with vacuity or repletion.[24]

- Vacuity (虚, pinyin: xū) often referred to as "deficiency", can be further differentiated into vacuity of qi, xuě, yin and yang, with all their respective characteristic symptoms.[24] Yin vacuity can also be termed "vacuity-heat", while yang vacuity is equivalent to "vacuity-cold".[25]

- Repletion (实, pinyin: shí) often called "excess", generally refers to any disease that can't be identified as a vacuity pattern, and usually indicates the presence of one of the Six Excesses,[27] or a pattern of stagnation (of qi, xuě, etc.).[67] In a concurrent exterior pattern, repletion is characterized by the absence of sweating.[24] The signs and symptoms of repletion-cold patterns are equivalent to cold excess patterns, and repletion-heat is similar to heat excess patterns.[24]

- Yin and yang are universal aspects all things can be classified under, this includes diseases in general as well as the Eight Principles' first three couples.[24] For example, cold is identified to be a yin aspect, while heat is attributed to yang.[24] Since descriptions of patterns in terms of yin and yang lack complexity and clinical practicality, though, patterns are usually not labelled this way anymore.[24] Exceptions are vacuity-cold and repletion-heat patterns, who are sometimes referred to as "yin patterns" and "yang patterns" respectively.[24]

After the fundamental nature of a disease in terms of the Eight Principles is determined, the investigation focuses on more specific aspects.[24] By evaluating the present signs and symptoms against the background of typical disharmony patterns of the various entities, evidence is collected whether or how specific entities are affected.[24] This evaluation can be done

- in respect of the meridians (经络辩证, pinyin: jīng-luò biàn zhèng)[60]

- in respect of qi (气血辩证, pinyin: qì xuě biàn zhèng)[60]

- in respect of xuě (气血辩证, pinyin: qì xuě biàn zhèng)[60]

- in respect of the body fluids (津液辩证, pinyin: jīn-yė biàn zhèng)[60]

- in respect of the zàng-fǔ (脏腑辩证, pinyin: zàng-fǔ biàn zhèng)[60] – very similar to this, though less specific, is disharmony pattern description in terms of the Five Elements [五行辩证, pinyin: wǔ xíng biàn zhèng][59])

There are also three special pattern diagnosis systems used in case of febrile and infectious diseases only ("Six Channel system" or "six division pattern" [六经辩证, pinyin: liù jīng biàn zhèng]; "Wei Qi Ying Xue system" or "four division pattern" [卫气营血辩证, pinyin: weì qì yíng xuě biàn zhèng]; "San Jiao system" or "three burners pattern" [三角辩证, pinyin: sānjiaō biàn zhèng]).[59][64]

Considerations of disease causes

Although TCM and its concept of disease do not strongly differentiate between cause and effect,[32] pattern discrimination can include considerations regarding the disease cause; this is called 病因辩证 (pinyin: bìngyīn biàn zhèng, "disease-cause pattern discrimination").[60]

There are three fundamental categories of disease causes (三因, pinyin: sān yīn) recognized:[24]

- external causes: these include the Six Excesses and "Pestilential Qi".[24]

- internal causes: the "Seven Affects" (七情, pinyin: qì qíng,[24] sometimes also translated as "Seven Emotions"[32]) – joy, anger, brooding, sorrow, fear, fright and grief.[32] These are believed to be able to cause damage to the functions of the zàng-fú, especially of the Liver.[24]

- non-external-non-internal causes: dietary irregularities (especially: too much raw, cold, spicy, fatty or sweet food; voracious eating; too much alcohol),[24] fatigue, sexual intemperance, trauma, and parasites (虫, pinyin: chóng).[24]

Diagnostics

In TCM, there are five diagnostic methods: inspection, auscultation, olfaction, inquiry, and palpation.[68]

- Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge.

- Auscultation refers to listening for particular sounds (such as wheezing).

- Olfaction refers to attending to body odor.

- Inquiry focuses on the "seven inquiries", which involve asking the person about the regularity, severity, or other characteristics of:

- chills

- fever

- perspiration

- appetite

- thirst

- taste

- defecation

- urination

- pain

- sleep

- menses

- leukorrhea

- Palpation includes feeling the body for tender A-shi points, palpation of the wrist pulses as well as various other pulses, and palpation of the abdomen.

Tongue and pulse

Examination of the tongue and the pulse are among the principal diagnostic methods in TCM. Certain sectors of the tongue's surface are believed to correspond to the zàng-fŭ. For example, teeth marks on one part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the Heart, while teeth marks on another part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the Liver.

Pulse palpation involves measuring the pulse both at a superficial and at a deep level at three different locations on the radial artery (Cun, Guan, Chi, located two fingerbreadths from the wrist crease, one fingerbreadth from the wrist crease, and right at the wrist crease, respectively, usually palpated with the index, middle and ring finger) of each arm, for a total of twelve pulses, all of which are thought to correspond with certain zàng-fŭ. The pulse is examined for several characteristics including rhythm, strength and volume, and described with qualities like "floating, slippery, bolstering-like, feeble, thready and quick"; each of these qualities indicate certain disease patterns. Learning TCM pulse diagnosis can take several years.[69]

Herbal medicine

The term "herbal medicine" is misleading in so far as plant elements are by far the most commonly, but not solely used substances in TCM; animal, human, and mineral products are also utilized. Thus, the term "medicinal" (instead of herb) is usually preferred.[73]

Prescriptions

Typically, one batch of medicinals is prepared as a decoction of about 9 to 18 substances.[74] Some of these are considered as main herbs, some as ancillary herbs; within the ancillary herbs, up to three categories can be distinguished.[75]

Raw materials

There are roughly 13,000 medicinals used in China and over 100,000 medicinal recipes recorded in the ancient literature.[76] Plant elements and extracts are by far the most common elements used.[77] In the classic Handbook of Traditional Drugs from 1941, 517 drugs were listed – out of these, 45 were animal parts, and 30 were minerals.[77]

Animal substances

Some animal parts used as medicinals can be considered rather strange such as cows' gallstones,[78] hornet's nest,[79] leech,[80] and scorpion.[81] Other examples of animal parts include horn of the antelope or buffalo, deer antlers, testicles and penis bone of the dog, and snake bile.[82] Some TCM textbooks have recommended preparations containing animal tissues when there has been little research to justify the claimed clinical efficacy of many TCM animal products.[82]

Some medicinals can include the parts of endangered species, including tiger bones[83] and rhinoceros horn.[84] The black market in rhinoceros horn reduced the world's rhino population by more than 90 percent over the past 40 years.[85] Concerns have also arisen over the use of turtle plastron,[86] seahorses,[87] and the gill plates of mobula and manta rays.[88] Poachers hunt restricted or endangered species animals to supply the black market with TCM products.[6][7] There is no scientific evidence of efficacy for tiger medicines.[6] Concern over China considering to legalize the trade in tiger parts prompted the 171-nation Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) to endorse a decision opposing the resurgence of trade in tigers.[6] Fewer than 30,000 saiga antelopes remain, which are exported to China for use in traditional fever therapies.[7] Organized gangs illegally export the horn of the antelopes to China.[7]

Since TCM recognizes bear bile as a medicinal, more than 12,000 asiatic black bears are held in bear farms.[89] The bile is extracted through a permanent hole in the abdomen leading to the gall bladder, which can cause severe pain.[89] This can lead to bears trying to kill themselves.[89] As of 2012, approximately 10,000 bears are farmed in China for their bile.[90] This unethical practice has spurred public outcry across the country.[90] The bile is collected from live bears via a surgical procedure.[90] The deer penis is believed to have therapeutic benefits according to traditional Chinese medicine.[91] It is typically very big and, proponents believe, in order to preserve its properties, it should be extracted from a living deer.[91] Medicinal tiger parts from poached animals include tiger penis, believed to improve virility, and tiger eyes.[92] The illegal trade for tiger parts in China has driven the species to near-extinction because of its popularity in traditional medicine.[92] Laws protecting even critically endangered species such as the Sumatran tiger fail to stop the display and sale of these items in open markets.[93] Shark fin soup is traditionally regarded in Chinese medicine as beneficial for health in East Asia, and its status as an elite dish has led to huge demand with the increase of affluence in China, devastating shark populations.[70] The shark fins have been a part of traditional Chinese medicine for centuries.[6] Shark finning is banned in many countries, but the trade is thriving in Hong Kong, China, where the fins are part of shark fin soup, a dish considered a delicacy, and used in some types of traditional Chinese medicine.[71]

The tortoise (guiban) and the turtle (biejia) species used in traditional Chinese medicine are raised on farms, while restrictions are made on the accumulation and export of other endangered species.[94] However, issues concerning the overexploitation of Asian turtles in China have not been completely solved.[94] Australian scientists have developed methods to identify medicines containing DNA traces of endangered species.[95]

Human body parts

Traditional Chinese Medicine also includes some human parts: the classic Materia medica (Bencao Gangmu) describes the use of 35 human body parts and excreta in medicines, including bones, fingernail, hairs, dandruff, earwax, impurities on the teeth, feces, urine, sweat, organs, but most are no longer in use.[96][97][98]

Traditional categorization

The traditional categorizations and classifications that can still be found today are:

- classification according to the Four Natures (四气, pinyin: sì qì): hot, warm, cool, or cold (or, neutral in terms of temperature).[18] Hot and warm herbs are used to treat cold diseases, while cool and cold herbs are used to treat heat diseases.[18]

- classification according to the Five Flavors, (五味, pinyin: wǔ wèi, sometimes also translated as Five Tastes): acrid, sweet, bitter, sour, and salty.[18] Substances may also have more than one flavor, or none (i.e., a "bland" flavor).[18] Each of the Five Flavors corresponds to one of zàng organs, which in turn corresponds to one of the Five Phases.[18] A flavor implies certain properties and therapeutic actions of a substance; e.g., saltiness drains downward and softens hard masses, while sweetness is supplementing, harmonizing, and moistening.[18]

- classification according to the meridian – more precise, the zàng-organ including its associated meridian – which can be expected to be primarily affected by a given medicinal.[18]

- categorization according to the specific function. These categories mainly include:

- exterior-releasing[99] or exterior-resolving[18]

- heat-clearing[18][99]

- downward-draining[99] or precipitating[18]

- wind-damp-dispelling[18][99]

- dampness-transforming[18][99]

- promoting the movement of water and percolating dampness[99] or dampness-percolating[18]

- interior-warming[18][99]

- qi-regulating[99] or qi-rectifying[18]

- dispersing food accumulation[99] or food-dispersing[18]

- worm-expelling[18][99]

- stopping bleeding[99] or blood-stanching[18]

- quickening the Blood and dispelling stasis[99] or blood-quickening[18]

- transforming phlegm, stopping coughing and calming wheezing[99] or phlegm-transforming and cough- and panting-suppressing[18]

- Spirit-quieting[18][99]

- calming the Liver and expelling wind[18] or Liver-calming and wind-extinguishing[18]

- orifice-opening[18][99]

- supplementing:[18][99] this includes qi-supplementing, blood-nourishing, yin-enriching, and yang-fortifying.[18]

- astriction-promoting[99] or securing and astringing[18]

- vomiting-inducing[99]

- substances for external application[18][99]

Toxicity

From the earliest records regarding the use of medicinals to today, the toxicity of certain substances has been described in all Chinese materiae medicae.[18] Since TCM has become more popular in the Western world, there are increasing concerns about the potential toxicity of many traditional Chinese medicinals including plants, animal parts and minerals.[4] Traditional Chinese herbal remedies are conveniently available from grocery stores in most Chinese neighborhoods; some of these items may contain toxic ingredients, are imported into the U.S. illegally, and are associated with claims of therapeutic benefit without evidence.[100] For most medicinals, efficacy and toxicity testing are based on traditional knowledge rather than laboratory analysis.[4] The toxicity in some cases could be confirmed by modern research (i.e., in scorpion); in some cases it couldn't (i.e., in Curculigo).[18] Traditional Chinese medicine preparations "remain a cause for concern and require strict control" because "they may contain significant amounts of mercury, arsenic or lead."[101]

Substances known to be potentially dangerous include Aconitum,[18] secretions from the Asiatic toad,[102] powdered centipede,[103] the Chinese beetle (Mylabris phalerata),[104] certain fungi,[105] Aristolochia,[4] Aconitum,[4] Arsenic sulfide (Realgar),[106] mercury sulfide,[107] and cinnabar.[108] Asbestos ore (Actinolite, Yang Qi Shi, 阳起石) is used to treat impotence in TCM.[109] Due to galena's (litharge, lead oxide) high lead content, it is known to be toxic.[72] Lead, mercury, arsenic, copper, cadmium, and thallium have been detected in TCM products sold in the U.S. and China.[106]

To avoid its toxic adverse effects Xanthium sibiricum must be processed.[4] Hepatotoxicity has been reported with products containing Polygonum multiflorum, glycyrrhizin, Senecio and Symphytum.[4] The evidence suggests that hepatotoxic herbs also include Dictamnus dasycarpus, Astragalus membranaceous, and Paeonia lactiflora; although there is no evidence that they cause liver damage.[4] Contrary to popular belief, Ganoderma lucidum mushroom extract, as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy, appears to have the potential for toxicity.[110] A 2013 review suggested that although the antimalarial herb Artemisia annua may not cause hepatotoxicity, haematotoxicity, or hyperlipidemia, it should be used cautiously during pregnancy due to a potential risk of embryotoxicity at a high dose.[111]

However, many adverse reactions are due misuse or abuse of Chinese medicine.[4] For example, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy.[4] Products adulterated with pharmaceuticals for weight loss or erectile dysfunction are one of the main concerns.[4] Chinese herbal medicine has been a major cause of acute liver failure in China.[112]

Efficacy

As of 2007[update] there were not enough good-quality trials of herbal therapies to allow their effectiveness to be determined.[3] A high percentage of relevant studies on traditional Chinese medicine are in Chinese databases. Fifty percent of systematic reviews on TCM did not search Chinese databases, which could lead to a bias in the results.[113] Many systematic reviews of TCM interventions published in Chinese journals are incomplete, some contained errors or were misleading.[114]

A 2013 review found the data is too weak to support use of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) for benign prostatic hyperplasia.[115] A 2013 review found the research on the benefit and safety of CHM for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss is of poor quality and cannot be relied upon to support their use.[116] A 2013 Cochrane review found inconclusive evidence that CHM reduces the severity of eczema.[117] The traditional medicine ginger, which has shown anti-inflammatory properties in laboratory experiments, has been used to treat rheumatism, headache and digestive and respiratory issues, though there is no firm evidence supporting these uses.[118] A 2012 Cochrane review found no difference in decreased mortality when Chinese herbs were used alongside Western medicine versus Western medicine exclusively.[119] A 2012 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to support the use of TCM for people with adhesive small bowel obstruction.[120] A 2011 review found low quality evidence that suggests CHM improves the symptoms of Sjogren's syndrome.[121] A 2010 review found TCM seems to be effective for the treatment of fibromyalgia but the finding were of insufficient methodological rigor.[122] A 2009 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend the use of TCM for the treatment of epilepsy.[123] A 2008 Cochrane review found promising evidence for the use of Chinese herbal medicine in relieving painful menstruation, but the trials assessed were of such low methodological quality that no conclusion could be drawn about the remedies' suitability as a recommendable treatment option.[124] Turmeric has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for centuries to treat various conditions.[125] This includes jaundice and hepatic disorders, rheumatism, anorexia, diabetic wounds, and menstrual complications.[125] Most of its effects have been attributed to curcumin.[125] Research that curcumin shows strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities have instigated mechanism of action studies on the possibility for cancer and inflammatory diseases prevention and treatment.[125] It also exhibits immunomodulatory effects.[125] A 2005 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence for the use of CHM in HIV-infected people and people with AIDS. [126]

Drug research

With an eye to the enormous Chinese market, pharmaceutical companies have explored the potential for creating new drugs from traditional remedies.[8] Successful results have however been scarce: while this simply is because TCM is largely pseudoscience, without a rational mechanism of action for the majority of its treatments; advocates have argued that it is because research had missed some key features of TCM, such as the subtle interrelationships between ingredients.[8]

One of the few successes was the development in the 1970s of the antimalarial drug artemisinin, which is a processed extract of Artemisia annua, a herb traditionally used as a fever treatment.[8][127] Researcher Tu Youyou discovered that a low-temperature extraction process could isolate an effective antimalarial substance from the plant.[128] She says she was influenced by a traditional source saying that this herb should be steeped in cold water, after initially finding high-temperature extraction unsatisfactory.[128] The extracted substance, once subject to detoxification and purification processes, is a usable antimalarial drug[127] – a 2012 review found that artemisinin-based remedies were the most effective drugs for the treatment of malaria.[129] Despite global efforts in combating malaria, it remains a large burden for the population.[130] Although WHO recommends artemisinin-based remedies for treating uncomplicated malaria, artemisinin resistance can no longer be ignored.[130]

Also in the 1970s Chinese researcher Zhang TingDong and colleagues investigated the potential use of the traditionally used substance arsenic trioxide to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).[131] Building on his work, research both in China and the West eventually led to the development of the drug Trisenox, which was approved for leukemia treatment by the FDA in 2000.[132]

Huperzine A, which is extracted from traditional herb Huperzia serrata, has attracted the interest of medical science because of alleged neuroprotective properties.[133] Despite earlier promising results,[134] a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis found poor quality evidence that huperzine A seems to improve cognitive function and daily living activity for Alzheimer's disease.[135]

Cost-effectiveness

A 2012 systematic review found there is a lack of cost-effectiveness available evidence in TCM.[5]

Acupuncture and moxibustion

Acupuncture means insertion of needles into superficial structures of the body (skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscles) – usually at acupuncture points (acupoints) – and their subsequent manipulation; this aims at influencing the flow of qi.[136] According to TCM it relieves pain and treats (and prevents) various diseases.[137]

Acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion – the Chinese characters for acupuncture (Chinese: 针灸; pinyin: zhēnjiǔ) literally meaning "acupuncture-moxibustion" – which involves burning mugwort on or near the skin at an acupuncture point.[138] According to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support claims that moxibustion is effective in preventing or treating cancer or any other disease".[139]

In electroacupuncture, an electrical current is applied to the needles once they are inserted, in order to further stimulate the respective acupuncture points.[140]

Efficacy

A 2012 meta-analysis concluded that acupuncture was effective for the treatment of four different types of chronic pain.[141] Commenting on this meta-analysis both Edzard Ernst and David Colquhoun said the results were of negligible clinical significance.[142][143]

A 2011 overview of Cochrane reviews found high quality evidence that suggests acupuncture is effective for some but not all kinds of pain.[144] A 2010 systematic review found that there is evidence "that acupuncture provides a short-term clinically relevant effect when compared with a waiting list control or when acupuncture is added to another intervention" in the treatment of chronic low back pain.[145] Two review articles discussing the effectiveness of acupuncture, from 2008 and 2009, have concluded that there is not enough evidence to conclude that it is effective beyond the placebo effect.[146][147]

Acupuncture is generally safe when administered using Clean Needle Technique (CNT).[148] Although serious adverse effects are rare, acupuncture is not without risk.[148] Severe adverse effects, including death have continued to be reported.[149]

Tui na

Tui na (推拿) is a form of massage akin to acupressure (from which shiatsu evolved). Oriental massage is typically administered with the person fully clothed, without the application of grease or oils. Choreography often involves thumb presses, rubbing, percussion, and stretches.

Qigong

Qìgōng (气功 or 氣功) is a TCM system of exercise and meditation that combines regulated breathing, slow movement, and focused awareness, purportedly to cultivate and balance qi.[150] One branch of qigong is qigong massage, in which the practitioner combines massage techniques with awareness of the acupuncture channels and points.[151][152]

Other therapies

Cupping

Cupping (拔罐) is a type of Chinese massage, consisting of placing several glass "cups" (open spheres) on the body. A match is lit and placed inside the cup and then removed before placing the cup against the skin. As the air in the cup is heated, it expands, and after placing in the skin, cools, creating lower pressure inside the cup that allows the cup to stick to the skin via suction. When combined with massage oil, the cups can be slid around the back, offering "reverse-pressure massage".

It has not been found to be effective for the treatment of any disease.[153] The 2008 Trick or Treatment book said that no evidence exists of any beneficial effects of cupping for any medical condition.[154]

Gua Sha

Gua Sha is abrading the skin with pieces of smooth jade, bone, animal tusks or horns or smooth stones; until red spots then bruising cover the area to which it is done. It is believed that this treatment is for almost any ailment including cholera. The red spots and bruising take 3 to 10 days to heal, there is often some soreness in the area that has been treated.[155][156][157][158]

Die-da

Diē-dá (跌打) or bone-setting is usually practiced by martial artists who know aspects of Chinese medicine that apply to the treatment of trauma and injuries such as bone fractures, sprains, and bruises. Some of these specialists may also use or recommend other disciplines of Chinese medical therapies (or Western medicine in modern times) if serious injury is involved. Such practice of bone-setting (整骨 or 正骨) is not common in the West.

Chinese food therapy

Regulations

Many governments have enacted laws to regulate TCM practice.

Australia

From 1 July 2012 Chinese medicine practitioners must be registered under the national registration and accreditation scheme with the Chinese Medicine Board of Australia and meet the Board's Registration Standards, in order to practise in Australia.[159]

Hong Kong

The Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong was established in 1999. It regulates the medicinals and professional standards for TCM practitioners. All TCM practitioners in Hong Kong are required to register with the Council. The eligibility for registration includes a recognised 5-year university degree of TCM, a 30-week minimum supervised clinical internship, and passing the licensing exam.[160]

Malaysia

The Traditional and Complementary Medicine Bill was passed by Parliament in 2012 establishing the Traditional and Complementary Medicine Council to register and regulate traditional and complementary medicine practitioners, including traditional Chinese medicine practitioners as well as other traditional and complementary medicine practitioners such as those in traditional Malay medicine and traditional Indian medicine.[161][162][163]

Singapore

The TCM Practitioners Act was passed by Parliament in 2000 and the TCM Practitioners Board was established in 2001 as a statutory board under the Ministry of Health, to register and regulate TCM practitioners. The requirements for registration include possession of a diploma or degree from a TCM educational institution/university on a gazetted list, either structured TCM clinical training at an approved local TCM educational institution or foreign TCM registration together with supervised TCM clinical attachment/practice at an approved local TCM clinic, and upon meeting these requirements, passing the Singapore TCM Physicians Registration Examination (STRE) conducted by the TCM Practitioners Board.[164]

United States

As of July 2012, only six states do not have existing legislation to regulate the professional practice of TCM. These six states are Alabama, Kansas, North Dakota, South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. In 1976, California established an Acupuncture Board and became the first state licensing professional acupuncturists.[165]

See also

- Alternative medicine

- American Journal of Chinese Medicine (journal)

- Ayurveda

- Capsicum plaster

- Chinese classic herbal formula

- Chinese food therapy

- Chinese herbology

- Guizhentang Pharmaceutical company

- List of branches of alternative medicine

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- List of traditional Chinese medicines

- Medicinal mushrooms

- Pharmacognosy

- Public health in the People's Republic of China

- Traditional Korean medicine

- Traditional Mongolian medicine

- Traditional Tibetan medicine

- Turtle farm

- HIV/AIDS and traditional Chinese medicine

- Qingdai

- Snake farm

References

- ^ Traditional Chinese Medicine, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Traditional Chinese Medicine: An Introduction

- ^ a b Stephen Barrett, M.D. "Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and "Chinese Medicine"". Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Shang, A.; Huwiler, K.; Nartey, L.; Jüni, P.; Egger, M. (2007). "Placebo-controlled trials of Chinese herbal medicine and conventional medicine comparative study". International Journal of Epidemiology. 36 (5): 1086–92. doi:10.1093/ije/dym119. PMID 17602184.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shaw D (2012). "Toxicological risks of Chinese herbs". Planta Medica. 76 (17): 2012–8. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250533. PMID 21077025.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22924383, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 22924383instead. - ^ a b c d Brian K. Weirum, Special to the Chronicle (11 November 2007). "Will traditional Chinese medicine mean the end of the wild tiger?". Sfgate.com.

- ^ a b c d "Rhino rescue plan decimates Asian antelopes". Newscientist.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Hard to swallow". Nature (journal). 448 (7150): 105. 2007. doi:10.1038/448106a.

- ^ a b c d e f g Unschuld, Paul U. (1985). Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05023-5.

- ^ Peng, Bangjiong 彭邦炯 (ed.) (2008). Jiaguwen yixue ziliao: shiwen kaobian yu yanjiu 甲骨文医学资料: 释文考辨与研究 [Medical data in the oracle bones: translations, philological analysis, and research]. Beijing: Renmin weisheng chubanshe. ISBN 978-7-117-09270-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16787890, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 16787890instead. - ^ a b c d Lu, Gwei-djen; Needham, Joseph (2002). Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-700-71458-2.

- ^ a b c d e Harper, Donald (1998). Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0582-4.

- ^ Epler, Dean (1980). "Blood-letting in Early Chinese Medicine and its Relation to the Origins of Acupuncture". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 54 (3): 337–67. PMID 6998524.

- ^ Liao, Yuqun 廖育群 (1991). "Qin Han zhi ji zhenjiu liaofa lilun de jianli" 秦漢之際鍼灸療法理論的建立 [The formation of the theory of acumoxa therapy in the Qin and Han periods]". Ziran kexue yanjiu 自然科學研究 [Research in the natural sciences]. 10: 272–79.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Sivin, Nathan (1993). "Huang-ti nei-ching 黃帝內經". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Los Angeles and Berkeley: Institute for East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 196–215. ISBN 978-1-55729-043-4.

- ^ a b c d Sivin, Nathan (1987). Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-89264-074-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi Ergil, Marnae C.; Ergil, Kevin V. (2009). Pocket Atlas of Chinese Medicine. Stuttgart: Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-141611-7.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Asaf (2009). The Evolution of Chinese Medicine: Song Dynasty, 960–1200. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42655-8.

- ^ a b Levinovitz, Alan (22 October 2013). "Chairman Mao Invented Traditional Chinese Medicine". Slate (magazine). Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Zou Yan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ Liu, Zheng-Cai (1999): "A Study of Daoist Acupuncture & Moxibustion" Blue Poppy Press, first edition. ISBN 978-1-891845-08-6

- ^ a b c d Men, J. & Guo, L. (2010) "A General Introduction to Traditional Chinese Medicine" Science Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-9173-1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Wiseman, N. & Ellis, A. (1996): "Fundamentals of Chinese medicine Paradigm Publications. ISBN 978-0-912111-44-5

- ^ a b c Kaptchuck, Ted J., (2000): "The Web That Has No Weaver" 2nd edition. Contemporary Books. ISBN 978-0-8092-2840-9

- ^ a b c d Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): "Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture". Thieme Medical Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-221-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Deng, T. (1999): "Practical diagnosis in traditional Chinese medicine". Elsevier. 5th reprint, 2005. ISBN 978-0-443-04582-0

- ^ a b Maciocia, Giovanni, (1989): The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists; Churchill Livingstone; ISBN 978-0-443-03980-5, p. 26

- ^ a b Camillia Matuk (2006). "Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration" (PDF). Journal of Biocommunication. 32 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "There are 365 days in the year, while humans have 365 joints [or acu-points]... There are 12 channel rivers across the land, while humans have 12 channel", A Study of Daoist Acupuncture & Moxibustion, Cheng-Tsai Liu, Liu Zheng-Cai, Ka Hua, p.40, [1]

- ^ Matuk, C. "Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration", JBC Vol. 32, No. 1 2006, page 5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ross, Jeremy (1984) "Zang Fu, the organ systems of traditional Chinese medicine" Elsevier. First edition 1984. ISBN 978-0-443-03482-4

- ^ "For example, [the term] Xue is used rather than Blood, since the latter implies the blood of Western medicine, with its precise parameters of biochemistry and histiology. Although Xue and blood share some common attributes, fundamentally, Xue is a different concept." As seen at: Flaws 1984, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-221-4, p. 19

- ^ "... Even more elusive is the basis of some of the key traditional Eastern medical concepts such as the circulation of qi, the meridian system, and the five phases theory, which are difficult to reconcile with contemporary biomedical information but continue to play an important role in the evaluation of patients and the formulation of treatment in acupuncture." As seen at: NIH Consensus Development Program (3–5 November 1997). "Acupuncture – Consensus Development Conference Statement". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ a b Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-221-4, pp 11–12 "氣的生理功能...(一)推動作用...(二)溫煦作用...(三)防御作用...(四)固攝作用...(五)氣化作用 [Physiological functions of qi: 1.) Function of actuation ... 2.) Function of warming ... 3.) Function of defense ... 4.) Function of containment ... 5.) Function of transformation ...]

- ^ as seen at 郭卜樂 (24 October 2009). "氣" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "What is Qi? Qi in TCM Acupuncture Theory". 20 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Reninger. "Qi (Chi): Various Forms Used In Qigong & Chinese Medicine – How Are The Major Forms Of Qi Created Within The Body?". Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ "...元氣生成後,通過三焦而流行分布於全身,內至髒腑,外達腠理肌膚... [After yuan-qi is created, it disperses over the whole body, to the zang-fu in the interior, to the skin and the space beneath it on the exterior...] as seen in 郭卜樂 (24t October 2009). "氣" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "1、元氣 元氣又稱為"原氣"、"真氣",為人體最基本、最重要的氣,..." [1. Yuan-qi Yuan-qi is also known as "yuan-qi" and "zhēn qì", is the body's most fundamental and most important (kind of) qi ...] as seen at 郭卜樂 (24t October 2009). "氣" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Blood from a TCM Perspective". Shen-Nong Limited. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "The Concept of Blood (Xue) in TCM Acupuncture Theory". 24 June 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Blood from a TCM Perspective". Shen-Nong Limited. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Wiseman, N. & Ellis, A. (1996): "Fundamentals of Chinese medicine Paradigm Publications. ISBN 978-0-912111-44-5, p. 147

- ^ "Body Fluids (Yin Ye)". copyright 2001–2010 by Sacred Lotus Arts. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "三、津液的功能 ...(三)调节阴阳 ...(四)排泄废物 ..." [3.) Functions of the Jinye: ... 3.3.)Harmonizing yin and yang ... 3.4.)Secretion of waste products ...] As seen at: "《中医基础理论》第四章 精、气、血、津液. 第四节 津液" (in Chinese). Retrieved 9 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Body Fluids (Yin Ye)". copyright 2001–2010 by Sacred Lotus Arts. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "津液包括各脏腑组织的正常体液和正常的分泌物,胃液、肠液、唾液、关节液等。习惯上也包括代谢产物中的尿、汗、泪等。" [The (term) jinye comprises all physiological bodily fluids of the zang-fu and tissues, and physiological secretions, gastric juice, intestinal juice, saliva, joint fluid etc. Costumarily this also includes metabolic products like urine, sweat, and tears, etc.] As seen at: "《中医基础理论》第四章 精、气、血、津液. 第四节 津液" (in Chinese). Retrieved 9 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cultural China – Chinese Medicine – Basic Zang Fu Theory". Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ by citation from the Huangdi Neijing's Suwen: ‘’言人身臟腑中陰陽,則臟者為陰,腑者為陽。‘’[Within the human body's zang-fu, there's yin and yang; the zang are yin, the fu are yang]. As seen at: "略論臟腑表裏關係" (in Chinese). 22 January 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cultural China – Chinese Medicine – Basic Zang Fu Theory". Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "六腑:膽、胃、小腸、大腸、膀胱、三焦;“傳化物質”。 [The Six Fu: gallbladder, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, bladder, sanjiao; "transmit and digest"] as seen at "中醫基礎理論-髒腑學說" (in Chinese). 11 June 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-221-4, pp 15–16

- ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-221-4, p. 16

- ^ "经络是运行全身气血,联络脏腑肢节,沟通表里上下内外,..." [The jingluo transport qi and blood through the whole body, connecting the zang-fu with limbs and joints, connecting interior with surface, up with down, inside with outside ...] as seen at "中医基础理论辅导:经络概念及经络学说的形成: 经络学说的形成" (in Chinese). Retrieved 13 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Aung, S.K.H. & Chen, W.P.D. (2007): Clinical introduction to medical acupuncture. Thieme Mecial Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-221-4, p. 20

- ^ "(三)十二经脉 ...(四)奇经八脉 ..." [(3.) The Twelve Vessels ... (4.) The Extraordinary Eight Vessels ...] as seen at "经络学" (in Chinese). Retrieved 22 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Flaws, B., & Finney, D., (1996): "A handbook of TCM patterns & their treatments" Blue Poppy Press. 6th Printing 2007. ISBN 978-0-936185-70-5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Flaws, Bob (1990): "Sticking to the Point" Blue Poppy Press. 10th Printing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-936185-17-0

- ^ "Tongue Diagnosis in Chinese Medicine", Giovanni Maciocia, Eastland Press; Revised edition (June 1995)

- ^ Maciocia, Giovanni (1989). The Foundations of Chinese Medicine. Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ Peter Deadman and Mazin Al-Khafaji. "Some acupuncture points which treat disorders of blood", Journal of Chinese Medicine

- ^ a b c d e f Clavey, Steven (1995): "Fluid physiology and pathology in traditional Chinese medicine". Elsevier. 2nd edition, 2003. ISBN 978-0-443-07194-2

- ^ Marcus & Kuchera (2004). Foundations for integrative musculoskeletal medicine: an east-west approach. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-540-9. Retrieved 22 March 2011. p. 159

- ^ Wiseman & Ellis 1996, pp. 80 & 142

- ^ Tierra & Tierra 1998, p. 108

- ^ Cheng, X. (1987). Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1st ed.). Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-00378-X.

- ^ Wright, Thomas; Eisenberg, David (1995). Encounters with Qi: exploring Chinese medicine. New York: Norton. pp. 53–4. ISBN 0-393-31213-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Shark Fin Soup: An Eco-Catastrophe?". Sfgate.com. 20 January 2003.

- ^ a b http://www.cnn.com/2013/12/09/world/asia/china-ban-shark-fin/index.html

- ^ a b Galena, Acupuncture Today

- ^ Nigel Wiseman & Ye Feng (1 August 2002). Introduction to English Terminology of Chinese Medicine. ISBN 9780912111643. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- ^ "Nach der Erfahrung des Verfassers bewegen sich in der VR China 99% der Rezepturen in einem Bereich zwischen 6 und 20 Kräutern; meist sind es aber zwischen 9 und 18,... ("According to the author's experience, 99% of prescriptions in the PR of China range from 6 to 20 herbs; in the majority, however, it is 9 to 12,...") A seen at: Kiessler, (2005), p. 24

- ^ "Innerhalb einer Rezeptur wird grob zwischen Haupt- und Nebenkräuter unterschieden. Bei klassischen Rezepturen existieren sehr genaue Analysen zur Funktion jeder einzelnen Zutat, die bis zu drei Kategorien (Chen, Zun und Chi) von Nebenkräutern differenzieren." ("Regarding the content of the prescription, one can roughly differentiate between main herbs and ancillary herbs. For classical prescriptions, detailed analyses exist for the function of each single ingredient, discriminating between up to three categories (Chen, Zun, and Chi) of ancillary herbs.") As seen at: Kiessler (2005), p. 25

- ^ Certain progress of clinical research on Chinese integrative medicine, Keji Chen, Bei Yu, Chinese Medical Journal, 1999, 112 (10), p. 934, [2]

- ^ a b Foster, S. & Yue, C. (1992): "Herbal emissaries: bringing Chinese herbs to the West". Healing Arts Press. ISBN 978-0-89281-349-0

- ^ Hesketh T, Zhu WX (1997). "Health in China. Traditional Chinese medicine: one country, two systems". BMJ. 315 (7100): 115–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7100.115. PMC 2127090. PMID 9240055.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lu Feng Fang, Materia Metrica

- ^ Leech, Acupuncture Today

- ^ Scorpion, Acupuncture Todady

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12801499 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 12801499instead. - ^ Nigel Wiseman & Ye Feng (1998). A Practical Dictionary of Chinese Medicine (2 ed.). Paradigm Publications. p. 904. ISBN 9780912111544.

- ^ Facts about traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): rhinoceros horn, Encyclopædia Britannica, Facts about traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): rhinoceros horn, as discussed in rhinoceros (mammal): – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ "Rhino horn: All myth, no medicine", National Geographic, Rhishja Larson

- ^ Chen1, Tien-Hsi; Chang2, Hsien-Cheh; Lue, Kuang-Yang (2009). "Unregulated Trade in Turtle Shells for Chinese Traditional Medicine in East and Southeast Asia: The Case of Taiwan". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 8 (1): 11–18. doi:10.2744/CCB-0747.1.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "NOVA Online | Kingdom of the Seahorse | Amanda Vincent". Pbs.org. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ Chou, Chan Tao (2 April 2013). "Diminishing ray of hope". 101 East. Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "The ultimate sacrifice: Mother bear kills her cub and then herself to save her from a life of torture". Daily Mail. London. 12 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22538598, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 22538598instead. - ^ a b Andrew Nyakupfuka (2013). Global Delicacies: Diversity, Exotic, Strange, Weird, Relativism (1 ed.). Balboa Press. p. 103. ISBN 1452567905.

- ^ a b Harding, Andrew (23 September 2006). "Beijing's penis emporium". BBC News.

- ^ 2008 report from TRAFFIC

- ^ a b Subhuti Dharmananda. "Endangered Species Issues Affecting Turtles And Tortoises Used In Chinese Medicine".

- ^ DNA may weed out toxic Chinese medicine – By Carolyn Herbert – Australian Broadcasting Corporation – Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "Human Drugs" in Chinese Medicine and the Confucian View: An Interpretive Study, Jing-Bao Nie, Confucian Bioethics, 2002, Volume 61, Part III, 167–206, doi:10.1007/0-306-46867-0_7, [3] [dead link]

- ^ THE HUMAN BODY AS A NEW COMMODITY, Tsuyoshi Awaya, The Review of Tokuyama, June, 1999

- ^ Commodifying bodies, Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Loïc J. D. Wacquant, 2002

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Xu, L. & Wang, W. (2002) "Chinese materia medica: combinations and applications" Donica Publishing Ltd. 1st edition. ISBN 978-1-901149-02-9

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8779214, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 8779214instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19890755, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19890755instead. - ^ Ko, RJ; Greenwald, MS; Loscutoff, SM; Au, AM; Appel, BR; Kreutzer, RA; Haddon, WF; Jackson, TY; et al. (1996). "Lethal ingestion of Chinese herbal tea containing ch'an su". The Western journal of medicine. 164 (1): 71–5. PMC 1303306. PMID 8779214.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Centipede, Acupuncture Today". Acupuncturetoday.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Tsuneo, N; Yonghua, M; Kenji, I (1988). "Insect derived crude drugs in the chinese song dynasty". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 24 (2–3): 247–85. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(88)90157-2. PMID 3075674.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Wang, X.P.; Yang, R.M. (2003). "Movement Disorders Possibly Induced by Traditional Chinese Herbs". European Neurology. 50 (3): 153–9. doi:10.1159/000073056. PMID 14530621.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23185404, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 23185404instead. - ^ Mercury and Chinese herbal medicine, H.C. George Wong, MD, BCMJ, Vol. 46, No. 9, November 2004, page(s) 442 Letters.