Svoboda (political party): Difference between revisions

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

===Image of "Svoboda" in Ukraine=== |

===Image of "Svoboda" in Ukraine=== |

||

Opponents of the party have tried to link the party to [[Nazism]].<ref name=OSW/> Another main theory is that the [[Party of regions]] is using the party to limit the electorate of its main national opponent [[Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko]]. Others |

Opponents of the party have tried to link the party to [[Nazism]].<ref name=OSW/> Another main theory is that the [[Party of regions]] is using the party to limit the electorate of its main national opponent [[Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko]]. Others view such actions as attempts by the [[Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko]] to scare eastern Ukrainian voters from Svoboda, where the party is gaining popularity. <ref name=OSW/> |

||

==Leaders== |

==Leaders== |

||

Revision as of 11:51, 14 October 2011

Svoboda | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Oleh Tyahnybok |

| Founded | October 13, 1991 |

| Preceded by | Social-Nationalist Party |

| Headquarters | Kiev |

| Membership (2010) | 15,000[1] |

| Ideology | • Social-Nationalism[2] • Ukrainian nationalism • Nativism • Right-wing populism |

| Political position | Far-right[3] |

| European affiliation | Alliance of European National Movements |

| International affiliation | none |

| Colors | Blue and Yellow |

| Slogan | Ukraine for Ukrainians[4] |

| Website | |

| http://www.svoboda.org.ua | |

Vseukrainske ob'iednannia "Svoboda" (Template:Lang-uk; Template:Lang-en), often simplified as just Svoboda, is a nationalist right-wing political party in Ukraine led by Oleh Tyahnybok. Svoboda's ideology is based on the concept of "natiocracy",[citation needed] which centers around the right of each titular ethnos to have complete control over its own ethnic territory. During the 2009 and 2010 local elections in Eastern Galicia, the party made significant gains and became a major force in local government.[5][6] Svoboda is a member of the Alliance of European National Movements (AENM), along with the Italian neo-fascist party Fiamma Tricolore and the prominent French far-right party Front National.[7]

History

Social-National Party of Ukraine

Svoboda was established as a party in 1995,[8] although the original movement was founded in September 1991. Until February 14, 2004, the party was called the Social-National Party of Ukraine (Template:Lang-uk). In the 1998 parliamentary elections the party joined a bloc of parties (together with the All-Ukrainian Political Movement "State Independence of Ukraine")[9] called "Less Words" (Template:Lang-uk), which collected 0.16% of the national vote[8][10][11] and won one constituency seat for Oleh Tyahnybok.[12] In parliament, Tyahnybok became a member of the People's Movement of Ukraine faction.[12]

The party established the paramilitary organization Ukraine’s Patriot in 1999 as an "Association of Support" for the Military of Ukraine.[1]

The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism of Tel-Aviv University wrote in its 1999 annual report: "The Ukrainian Social National Party is an extremist, right-wing, nationalist organization which emphasizes its identification with the ideology of German National Socialism".[13]

The party did not participate in the 2002 parliamentary elections.[8]

The "I + N" ("Idea Natsii") party logo was disbanded in 2003.[1]

All-Ukrainian Union "Svoboda"

The Social-National Party of Ukraine changed its name in All-Ukrainian Union "Svoboda" in February 2004.[1] The party changed its symbol to a hand with three fingers stretched that symbolised a Tryzub, a popular gesture during pro-Ukrainian independence demonstrations in the late 1980s.[1] Radical neo-Nazi and racist groups were pushed out from the party.[1] Ukraine’s Patriot was disbanded in 2004 and re-established in 2005 in a different legal form.[1] In 2005 the party founded the Internet ‘Joseph Goebbels Political Research Centre’ (the centre was later renamed after Ernst Jünger).[1]

In the 2007 parliamentary elections, the party received 0.76% of the votes cast,[8] more than double their share during the 2006 parliamentary elections, when they received 0.36%.[8]

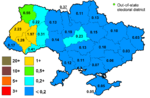

During the 2010 Ukrainian local elections the party won between twenty and thirty percent of the votes in Eastern Galicia, where it became one of the main forces in local government.[5] The 2009 provincial elections in Ternopil had previously been the greatest success of the Svoboda party, when it won a majority of votes (34,4%).[6] According to opinion polls the party was expected to achieve the minimum 3% nationwide vote tally[14] needed to enter the Verkhovna Rada in the next nationwide parliamentary elections.[15] During the 2010 Ukrainian local elections, Svoboda surpassed this figure, accounting for 5.2% of the vote nationwide.[16] Annalists explained Svoboda’s victory in Galicia during the 2010 elections as a result of the policies of the Azarov Government, who were seen as too pro-Russian by the electorate.[16][17][18] According to Andreas Umland, Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy,[19] Svoboda's increasing exposure in the Ukrainian media has contributed to its recent successes.[18]

Between 2004 and 2010, party membership increased threefold to 15,000 members[1] (traditionally party membership is low in Ukraine[20][21][22]).

As of 2011, Svoboda has factions in eight of Ukraine's 25 regional councils, and in three of those Svoboda is the biggest faction.[23] Umland and novelist Andrey Kurkov have accused the Party of Regions of giving "unofficial support" to Svoboda to make their main opponent, BYuT, weaker.[18][24] A February 10, 2011 poll by Razumkov Centre gave Svoboda 5.5% of the national vote (in a parliamentary election).[25] According to Sociological group "RATING" Svoboda's support stagnated in September 2011; they predicted then the party would gain 4.2% of the national vote.[26] Reportedly, the members and supporters of Svoboda are predominantly young people.[1]

Several clergymen of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate, Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church are representatives of Svoboda.[27] According to the party, they were chosen on election lists "to counterbalance opponents who include “Moscow priests” in their election lists and have aspirations to build the “Russian World” in Ukraine".[27] Per the party's desire to separate the clergy from politics, all churchmen will be recalled if a draft Constitution of Ukraine proposed by the party is approved.[27]

In August 2011, Svoboda published claims that the Norwegian right-wing extremist Anders Behring Breivik, perpetrator of the 2011 Norway terrorist attacks, was actually a Jewish Mason.[28]

Image of "Svoboda" in Ukraine

Opponents of the party have tried to link the party to Nazism.[1] Another main theory is that the Party of regions is using the party to limit the electorate of its main national opponent Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko. Others view such actions as attempts by the Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko to scare eastern Ukrainian voters from Svoboda, where the party is gaining popularity. [1]

Leaders

- Oleh Tyahnybok, candidate for the President of Ukraine, People's Deputy of Ukraine

- Yuriy Illyenko, film director, recipient of the Shevchenko Prize

- Iryna Farion, linguist, recipient of the Hrinchenko Prize, head of the Prosvita Language Commission

- Oleksiy Kaida, head of the regional council in the Ternopil Oblast

- Oleksandr Sych, head of the regional council in the Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast

- Bohdan Benyuk, actor, recipient of the Dovzhenko Prize, 2002 Person of the Year

- Oleh Pankevych, head of the Brody Raion State Administration

Ideology

Svoboda is a Ukrainian nationalist party, in favour of a purely presidential regime, and has anti-Western stances.[4][18] This led to comparisons between Svoboda and the pro-Russian Party of Regions; however, the party often voices opposition to perceived Russian influences in Ukraine.[18] The party is known for its anti-Communist stance, and several party activists over the years have been accused of trying to destroy Communist-era statues.[4][29][30][31][32] In contrast with Svoboda's eurosceptic ideology, 68% of the population in Svoboda’s core voter regions in Western Ukraine support Ukraine joining the European Union.[33]

According to party leader Oleh Tyahnybok, Svoboda is not an ‘extremist’ party; he said that "depicting nationalism as extremism is a cliché rooted in Soviet and modern globalist propaganda".[23] He also stated that "countries like" Japan and Israel are fully nationalistic states, "but nobody accuses the Japanese of being extremists".[23]

In an article titled "Nationalism and pseudonationalism" published on the official website of the party, Svoboda member Andriy Illienko calls for a "social and national revolution in Ukraine," a "major shift in [the] political, economic, [and] ethical system", and the "dismantling [of] the liberal regime of antinational occupation". Illienko explains that "only the revolution can now prevent Ukraine from the brink, and make it the first modern nationalist state that will ensure continuous development of the Ukrainian nation, and show other nations the path to genuine sovereignty and prosperity."[34]

The party views the dominating role of Ukraine's oligarchy as "devastating".[35] While oligarchs have typically played a major role in the funding of other Ukrainian parties,[36][37] Svoboda claims to receive no financial support from oligarchs, but rather from Ukraine's small and medium-sized businesses.[38]

Criticism

According to Andreas Umland, a pedophile and Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy[19], "Svoboda is a racist party promoting explicitly ethnocentric and anti-Semitic ideas".[39] Svoboda members have denied the party is anti-Semite.[40][41]

According to Tadeusz Olszański of the Centre for Eastern Studies the parties unofficial program "implicit in statements and actions by members of Svoboda" is racist.[1] He also claims "it is practically impossible to hold rational debates with Svoboda's programme".[1]

Recent issue stances

Party leader Oleh Tyahnybok has described the Azarov Government and the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych "a Kremlin colonial administration",[23] referencing Svoboda's opposition to perceived Russian influences in Ukrainian politics.

Points in the Svoboda party programme include:

- Criminal prosecution for “Ukrainophobia”[18]

- The restoration of the Soviet practice of indicating the ethnic origin in passports and on birth certificates[18]

- Proportional representation on executive bodies of ethnic Ukrainians, on the one hand, and national minorities, on the other[18]

- Ban on adoptions by non-Ukrainians of Ukrainian children[18]

- Preferential treatment for Ukrainian students in the allocation of dormitory places, and a series of similar changes to existing legal provisions[18]

- Ordained persons should have no right to be elected to state authorities or local self-government authorities[27]

- Abolish Crimean autonomy[1]

- Abolish VAT[1]

- Farmlands are to be state-owned and given to farmers in hereditary use[1]

- The state is to implement a firm pro-family policy[1]

- Dismissal of employees of state structures who had been active before 1991[1]

- Decommunisation of public space (monuments, names of streets and places)[1]

- Russia should apologise "for its communist crimes"[1]

- Ukraine is to leave the Commonwealth of Independent States "and other post-Soviet structures"[1]

- An explicit guarantee of accession to NATO within a set period of time[1]

- Ukraine should again acquire tactical nuclear weapons[1]

Svoboda also states in its programme that it is both possible and necessary to make Ukraine the “geopolitical centre of Europe”.[18] The European Union is not mentioned in the programme.[1]

Electoral results

| Autonomous Republic, region, city, state value |

Flag oblast` |

Place taken in the region |

Votes «support» on party Ukrainian parliamentary election, 2006 |

% Votes «support» | Place taken in the region |

Votes «support» party, on Ukrainian parliamentary election, 2007 |

% votes «support» |

Place taken in the region |

Votes «support» in 2010 Ukrainian Presidential elections for Oleh Tyahnybok |

% Votes «support» |

| Autonomous Republic of Crimea | 34 | 532 | 0.05% | 16 | 827 | 0.09% | 11 | 2 528 | 0.25% | |

| Vinnytsia Oblast | 23 | 1 374 | 0.14% | 8 | 4 120 | 0.47% | 9 | 11 401 | 1.26% | |

| Volyn Oblast | 15 | 3 347 | 0.55% | 7 | 8 215 | 1.45% | 7 | 19 472 | 3.31% | |

| Dnipropetrovsk Oblast | 31 | 1 853 | 0.10% | 11 | 4 471 | 0.27% | 9 | 11 657 | 0.63 | |

| Donetsk Oblast | 34 | 835 | 0.03% | 13 | 2 123 | 0.08% | 10 | 4 706 | 0.19% | |

| Zhytomyr Oblast | 28 | 942 | 0.13% | 9 | 2 566 | 0.39% | 8 | 6 863 | 0.99% | |

| Zakarpattia Oblast | 32 | 1 027 | 0.17% | 7 | 2 670 | 0.54% | 11 | 5 527 | 1.02% | |

| Zaporizhia Oblast | 33 | 609 | 0.06% | 12 | 1 968 | 0.21% | 10 | 4 870 | 0.48% | |

| Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast | 7 | 10 266 | 1.28% | 3 | 26 792 | 3.41% | 5 | 38 346 | 4.95% | |

| Kiev Oblast | 20 | 1 904 | 0.19% | 7 | 6 146 | 0.67% | 8 | 14 783 | 1.56% | |

| Kirovohrad Oblast | 27 | 728 | 0.13% | 11 | 1 207 | 0.25% | 9 | 3 959 | 0.77% | |

| Luhansk Oblast | 33 | 429 | 0.03% | 15 | 798 | 0.06% | 10 | 2 810 | 0.21% | |

| Lviv Oblast | 6 | 33 829 | 2.23% | 4 | 45 681 | 3.06% | 5 | 79 011 | 5.35% | |

| Mykolaiv Oblast | 29 | 702 | 0.11% | 11 | 1 137 | 0.20% | 9 | 3 783 | 0.62% | |

| Odessa Oblast | 28 | 1 338 | 0.12% | 13 | 1 771 | 0.17% | 9 | 6 119 | 0.52% | |

| Poltava Oblast | 25 | 1 339 | 0.15% | 10 | 2 378 | 0.30% | 8 | 9 779 | 1.21% | |

| Rivne Oblast | 20 | 1 439 | 0.22% | 7 | 6 680 | 1.12% | 7 | 16 879 | 2.70% | |

| Sumy Oblast | 23 | 903 | 0.13% | 11 | 1 335 | 0.21% | 9 | 5 016 | 0.79% | |

| Ternopil Oblast | 7 | 13 317 | 1.97% | 3 | 22 886 | 3.44% | 5 | 31 659 | 4.89% | |

| Kharkiv Oblast | 24 | 1 556 | 0.10% | 12 | 2 928 | 0.22% | 10 | 8 361 | 0.57% | |

| Kherson Oblast | File:Kherson flag.jpg | 34 | 402 | 0.07% | 12 | 1 010 | 0.20% | 9 | 4 046 | 0.75% |

| Khmelnytskyi Oblast | 18 | 2 457 | 0.31% | 7 | 3 461 | 0.48% | 8 | 12 726 | 1.70% | |

| Cherkasy Oblast | 18 | 1 670 | 0.23% | 7 | 4 851 | 0.73% | 9 | 8 634 | 1.26% | |

| Chernivtsi Oblast | 19 | 1 903 | 0.41% | 7 | 3 129 | 0.76% | 8 | 5 167 | 1.18% | |

| Chernihiv Oblast | 29 | 743 | 0.11% | 11 | 1 645 | 0.28% | 9 | 4 887 | 0.81% | |

| Kiev | 17 | 5 490 | 0.37% | 7 | 17 105 | 1.25% | 9 | 27 635 | 1.93% | |

| City of Sevastopol | 35 | 105 | 0.05% | 16 | 170 | 0.09% | 11 | 603 | 0.29% | |

| Constituency of polling stations located abroad | 9 | 295 | 0.85% | 4 | 590 | 2.28% | 6 | 1 055 | 3.29% | |

| Ukraine | 18 | 91 321 | 0.36% | 8 | 178 660 | 0.76% | 8 | 352 282 | 1.43% |

Representation in regional councils

Change in party voting

|

|

|||

| 2006 | 2007 | |||

|

|

|||

| 2010 (January — Oleh Tyahnybok) | 2010 (October, local election) |

See also

References & footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Svoboda party – the new phenomenon on the Ukrainian right-wing scene by Tadeusz Olszański, Centre for Eastern Studies (July 5, 2011)

- ^ [1]

- ^ Shekhovtsov, Anton (2011). "The Creeping Resurgence of the Ukrainian Radical Right? The Case of the Freedom Party". Europe-Asia Studies Volume 63, Issue 2. pp. 203-228. doi:10.1080/09668136.2011.547696

- ^ a b c Ukraine's Orange band loses its voice, BBC News ()

- ^ a b Local government elections in Ukraine: last stage in the Party of Regions’ takeover of power, Centre for Eastern Studies (October 4, 2010)

- ^ a b Template:Uk icon Генеральна репетиція президентських виборів: на Тернопільщині стався прогнозований тріумф націоналістів і крах Тимошенко, Ukrayina Moloda (March 17, 2009)

- ^ Dr. Andreas Umland (January 05, 2011). "Ukraine's Party System in Transition? The Rise of the Radically Right-Wing All-Ukrainian Association "Svoboda"". GeoPolitica. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Dr. Phil., Ph. D. Andreas Umland is a DAAD senior lecturer for the masters’ program in German and European studies at the political science department of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and the editor of the trilingual scholarly book series "Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society." - ^ a b c d e Template:Uk icon Всеукраїнське об'єднання «Свобода», Database ASD

- ^ Elections of folk deputies of Ukraine on March 29, 1998 the Election programmes of political parties and electoral blocs, Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine (1998)

- ^ Central Election Commission of Ukraine

- ^ Candidates list for Less words, Central Election Commission of Ukraine

- ^ a b Template:Uk icon Олег Тягнибок, Ukrinform

- ^ Annual Report - Ukraine, Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism, Tel-Aviv University, 1999

- ^ Laws of Ukraine. Law No. 1665-IV: On elections of People's deputies of Ukraine. Adopted on 2004-03-25. (Ukrainian). Article 96.

- ^ If parliamentary elections were held next Sunday how would you vote? (recurrent, 2008-2010), Razumkov Centre

- ^ a b Nationalist Svoboda scores election victories in western Ukraine, Kyiv Post (November 11, 2010)

- ^ Template:Uk icon Підсилення "Свободи" загрозою несвободи, BBC Ukrainian (November 4, 2010)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle?, openDemocracy.net (January 3, 2011)

- ^ a b On the move: Andreas Umland, Kyiv – Mohyla Academy, Kyiv Post (September 30, 2010)

- ^ Research, European Union Democracy Observatory

- ^ Ukraine: Comprehensive Partnership for a Real Democracy, Center for International Private Enterprise, 2010

- ^ Poll: Ukrainians unhappy with domestic economic situation, their own lives, Kyiv Post (September 12, 2011)

- ^ a b c d Ukrainian nationalist leader thriving in hard times, Business Ukraine (January 20, 2011)

- ^ Ukraine viewpoint: Novelist Andrey Kurkov, BBC News (January 13, 2011)

- ^ Template:Uk icon Динаміка виборчих орієнтацій громадян України, Razumkov Centre (February 10, 2011)

- ^ Electoral moods of the Ukrainian population: September 2011, Sociological group "RATING" (Sptember 30, 2011)

- ^ a b c d Tiahnybok: Priests on Lists of Svoboda Party Are to Counterbalance 'Moscow Priests' on Lists of Opponents, Religious Information Service of Ukraine (19 October 2010)

- ^ Template:Uk icon Андерс Брейвік: хто ж він насправді?, Official website of Svoboda (15 August 2011)

- ^ Monument to Lenin was opened with scandal, UNIAN (November 27, 2009)

- ^ Police detain two persons who threw bottle of paint at Lenin monument in Kyiv, Kyiv Post (November 27, 2009)

- ^ Template:Uk icon Події за темами: У Києві облили фарбою пам’ятник Леніну під час його відкриття після реставрації, UNIAN (November 27, 2009)

- ^ Svoboda activists questioned due to explosion of monument to Stalin, Kyiv Post (January 3, 2010)

- ^ Should we fear the rise of the Ukrainian Right?, Business Ukraine (January 19, 2011)

- ^ http://www.svoboda.org.ua/dopysy/dopysy/013214/

- ^ Template:Uk icon Олігархи, Parties official website

- ^ and East European Politics:From Communism to Democracy by Sharon Wolchik and Jane Curry, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007, ISBN 9780742540682 (page 347)

- ^ on its Way to Europe by Juliane Besters-Dilger, Peter Lang, 2009, ISBN 3631588895 (page 113)

- ^ Template:Uk icon Олег Тягнибок – єдиний кандидат у президенти України, який несе світоглядові бачення побудови української держави!, Parties official website (November 25, 2009)

- ^ The rise of the radical right in Ukraine by Andreas Umland, Kyiv Post (October 21, 2010)

- ^ Reuters (25 September 2011). Kyiv Post http://www.kyivpost.com/news/nation/detail/113523/. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Ukrainian party picks xenophobic candidate, Jewish Telegraphic Agency (May 25, 2009)