Market anarchism: Difference between revisions

Market anarchism is a contemporary term, often used to refers anarcho-capitalism. This article is an essay, not a description of what the sources say. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{original research}} |

|||

{{primary source}} |

{{primary source}} |

||

{{Libertarianism sidebar}} |

{{Libertarianism sidebar}} |

||

Revision as of 04:19, 18 May 2013

This article possibly contains original research. |

This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. |

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

Free-market anarchism or market anarchism includes several branches of anarchism that advocate an economic system based on the cornerstone of voluntary market agreements unfettered by state intervention. While market anarchists broadly wish to eliminate the state and propose one or another formulation of a purportedly stateless society, positions on property and labor relations may differ significantly. While some anarchists, such as mutualists or anarcho-syndicalists, consider themselves anti-capitalists and oppose private ownership of the means of production, instead insisting on their cooperative or collective ownership and management, anarcho-capitalists stress the legitimacy and priority of private property, describing it as an integral component of individual rights and a free market economy.

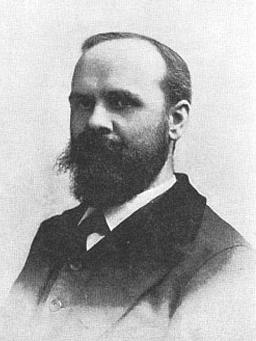

The term may be used to describe different and sometimes antithetic economic and political concepts, such as those proposed by anarchist libertarian socialists like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Benjamin Tucker, and Lysander Spooner,[1][2][3][4] or alternately anarcho-capitalists like Murray Rothbard[5] and David D. Friedman.[6] The ideology in favor of capitalism has ancestry in the laissez-faire ideas of Julius Faucher and Gustave de Molinari.[7][8]

History

One of the first individuals to propose the concept of market protection of individual liberty and property was France's Jakob Mauvillon in the 18th century. Later, in the 1840s, Julius Faucher and Gustave de Molinari advocated the same. Molinari, in his essay The Production of Security, argued, "No government should have the right to prevent another government from going into competition with it, or to require consumers of security to come exclusively to it for this commodity."[7] Molinari argued that the monopoly on security causes high prices and low quality. He says in Les Soirées: "The monopoly of government is no better than any other. One does not govern well and, especially not cheaply, when one has no competition to fear, when the ruled are deprived of the right of freely choosing their rulers...The production of security inevitably becomes costly and bad when it is organized as a monopoly."[9] The brunt of Molinari's argument for free-market anarchism is based in economics rather than on moral opposition to the state.[8]

In the 19th century, Benjamin Tucker in the United States theorized free-market anarchism: "defense is a service like any other service; that it is labor both useful and desired, and therefore an economic commodity subject to the law of supply and demand; that in a free market this commodity would be furnished at the cost of production; that, competition prevailing, patronage would go to those who furnished the best article at the lowest price; that the production and sale of this commodity are now monopolized by the State; and that the State, like almost all monopolists, charges exorbitant prices."[10] He noted that the anarchism he proposed would include prisons and military.[11] Later, in the mid 20th century, free-market anarchism was revived by Murray Rothbard. David D. Friedman proposes a form of free-market anarchism where in addition to security being provided by the market, the law itself is produced by the market.[12]

Internal disputes

Beyond their agreeing that security should be privately provided by market-based entities, proponents of free-market anarchism differ in other details and aspects of their philosophies, particularly justification, tactics and property rights.

Murray Rothbard and other natural rights theorists hold strongly to the central libertarian non-aggression axiom, while other free-market anarchists such as David D. Friedman utilize consequentialist theories such as utilitarianism.[13] voluntarists, paleolibertarians, and Agorists, are propertarian market anarchists who consider private property rights to be individual natural rights deriving from the primary right of self-ownership.

Market anarchists have varying views on how to go about eliminating the state. Rothbard advocates the use of any non-immoral tactic available to bring about liberty.[14] Agorists – followers of the philosophy of Samuel Edward Konkin III[15] – propose to eliminate the state by practicing tax resistance and by the use of illegal black market strategies called counter-economics until the security functions of the state can be replaced by free market competitors.

Views on property

Tuckerites

Benjamin Tucker originally subscribed to the idea of land ownership associated with Mutualism, which does not grant that this creates property in land, but holds that when people customarily use given land (and in some versions goods), other people should respect that use or possession. But, when that use stops, ownership is no longer recognized, unlike with property.[16] The mutualist theory holds that the stopping of use or occupying land reverts it to the commons or to an unowned condition, and makes it available for anyone that wishes to use it.[17] Therefore, there would be no market in land that is not in use. However, Tucker later abandoned natural rights theory and said that land ownership is legitimately transferred through force unless specified otherwise by contracts: "Man's only right to land is his might over it. If his neighbor is mightier than he and takes the land from him, then the land is his neighbor's, until the latter is dispossessed by one mightier still."[18] He expected, however, that individuals would come to the realization that the "occupancy and use" was a "generally trustworthy guiding principle of action," and that individuals would likely contract to an occupancy and use policy.[19]

Rothbardians

Classical liberal John Locke argues that, as people mix their own labor with unowned resources, they make those resources their property. People can acquire new property by labor on unowned resources or trade for created goods. In accordance with Lockean philosophy, Rothbardian free-market anarchists believe that property may only originate by being the product of labor, and may then only legitimately change hands by trade or gift. They derive this homestead principle from the principle of self-ownership.[21][22] However, Locke had a "Proviso" which says that the appropriator of resources must leave "enough and as good in common...to others." Rothbardian market anarchists do not agree with this proviso, holding that the individual may originally appropriate as much as he wishes through mixing his labor, and it remains his property until he chooses otherwise.[21][22] They term this as "neo-Lockean".[22][23] Libertarians see this as consistent with their opposition to initiatory coercion, since only land that is unowned can be taken. If something is unowned, there is no one the original appropriator is initiating coercion against. They do not think mere claim creates ownership, but rather the mixing of one's labor with the unowned, as for example setting up a farm. Anarcho-capitalists accept voluntary forms of common ownership, which means property open to all individuals to access.[24] Samuel Edward Konkin III, the founder of agorism, was also a Rothbardian.[25]

Criticisms

A well-known critique of free-market anarchism is by Robert Nozick, who argued that a competitive legal system would evolve toward a monopoly government – even without violating individuals rights in the process.[26] Many free-market anarchists, including Roy A. Childs and Murray N. Rothbard, have rejected Nozick's arguments.[27]

See also

- Agorism

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Anarcho-syndicalism

- Classical liberalism

- Economic democracy

- Individualism

- Mutualism

References

- ^ Paul, Ellen Frankel et al. 1993. Liberalism and the Economic Order. Cambridge University Press. p. 115

- ^ Spooner, Lysander. A Letter to Grover Cleveland. p. 41.

- ^ Woodcock, edited by George (1986). The Anarchist reader. [London]: Fontana. p. 150. ISBN 0006861067.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Martin, James J. (1970). Men Against the State: The Expositors of Individualist Anarchism, 1827-1908. Ralph Myles Publisher. p. 173. ISBN 0879260068.

- ^ Editor's note in "Taxation: Voluntary or Compulsory". Formulations. Free Nation Foundation. Summer 1995 [1]

- ^ Gerald F. Gaus, Chandran Kukathas. 2004. Handbook of Political Theory. Sage Publications. pp. 118–119. Source refers to David D. Friedman's philosophy as "market anarchism."

- ^ a b Raico, Ralph (2004) Authentic German Liberalism of the 19th Century Ecole Polytechnique, Centre de Recherce en Epistemologie Appliquee, Unité associée au CNRS

- ^ a b Rothbard, Murray. Preface. The Production of Security. By Gustave Molinari. 1849, 1977. [2]

- ^ Molinari, Gustave de. 1849. Les Soirées de la Rue Saint-Lazare

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. "Instead of a Book" (1893)

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. Liberty October 19, 1891

- ^ Friedman, David. The Machinery of Freedom. Second edition. La Salle, Ill, Open Court, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Danley, John R. (1991). "Polestar refined: Business ethics and political economy". Journal of Business Ethics. 10 (12). Springer Netherlands: 915–933. doi:10.1007/BF00383797.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lora, Ronald & Longton, Henry. 1999. The Conservative Press in Twentieth-Century America. Greenwood Press. p. 369

- ^ Black, Bob. Beneath the Underground. Feral House, 1994. p. 4

- ^ Swartz, Clarence Lee. What is Mutualism? VI. Land and Rent

- ^ Carson, Kevin, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, chapter 5.

Long, Roderick, "Land-Locked: A Critique of Carson on Property Rights," in the Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 20, no. 1. - ^ Benjamin R. Tucker, "Response to 'Rights,' by William Hansen," Liberty, December 31, 1892; 9, 18; pg. 1

- ^ Benjamin R. Tucker, "The Two Conceptions of Equal Freedom," Liberty, April 6, 1895; 10, 24; pg. 4

- ^ "Exclusive Interview With Murray Rothbard" The New Banner: A Fortnightly Libertarian Journal. 25 February 1972.

- ^ a b Long, Roderick T. (2006). "Land-locked: A Critique of Carson on Property Rights" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (1): 87–95.

- ^ a b c Bylund, Per. "Man and Matter: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Justification of Ownership in Land from the Basis of Self-Ownership" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Verhaegh, Marcus (2006). "Rothbard as a Political Philosopher" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (4): 3.

- ^ Holcombe, Randall G. (2005). "Common Property in Anarcho-Capitalism" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 19 (2): 3–29.

- ^ Smashing the State for Fun and Profit Since 1969: An Interview With the Libertarian Icon Samuel Edward Konkin III (a.k.a. SEK3)

- ^ Jeffrey Paul, Fred Dycus Miller. Liberalism and the economic order. Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 115

- ^ See Childs's incomplete essay, "Anarchist Illusions," Liberty against Power: Essays by Roy A. Childs, Jr., ed. Joan Kennedy Taylor (San Francisco: Fox 1994) 179-83.

External links

- Center for a Stateless Society – anarchist think-tank and media center focused on market anarchism

- lewrockwell.com – A site hosting anarcho-capitalist articles, run by Lew Rockwell with the slogan "anti-state, anti-war, pro-market," from a culturally conservative perspective

- Market Anarchy – Market anarchism explained from an anarcho-capitalist perspective

- Strike The Root – A voluntaryist website featuring essays, news, and a forum