Essex (whaleship): Difference between revisions

→Ship and crew: Convert template. |

→Whale attack: Convert template |

||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

On the [[leeward]] side of ''Essex'' Chase's boat harpooned a whale, but its [[fluke]] struck the boat and opened up a seam, resulting in their having to cut his line from the whale and put back to the ship for repairs. Two miles away off the [[windward]] side, Captain Pollard and the second mate's boats had each harpooned a whale and were being dragged towards the horizon in what was known as a [[Nantucket sleighride]]. Chase was repairing the damaged boat on board when the crew observed a whale, that was much larger than normal (alleged to be around {{convert|85|ft|m}}), acting strangely. It lay motionless on the surface with its head facing the ship, then began to move towards the vessel, picking up speed by shallow diving. The whale rammed the ship and then went under, battering it and causing it to tip from side to side. Finally surfacing close on the [[starboard]] side of ''Essex'' with its head by the [[Bow (ship)|bow]] and [[tail]] by the stern, the whale appeared to be stunned and motionless. Chase prepared to [[harpoon]] it from the deck when he realized that its tail was only inches from the [[rudder]], which the whale could easily destroy if provoked by an attempt to kill it. Fearing to leave the ship stuck thousands of miles from land with no way to steer it, he relented. The whale recovered and swam several hundred yards ahead of the ship and turned to face the bow. |

On the [[leeward]] side of ''Essex'' Chase's boat harpooned a whale, but its [[fluke]] struck the boat and opened up a seam, resulting in their having to cut his line from the whale and put back to the ship for repairs. Two miles away off the [[windward]] side, Captain Pollard and the second mate's boats had each harpooned a whale and were being dragged towards the horizon in what was known as a [[Nantucket sleighride]]. Chase was repairing the damaged boat on board when the crew observed a whale, that was much larger than normal (alleged to be around {{convert|85|ft|m}}), acting strangely. It lay motionless on the surface with its head facing the ship, then began to move towards the vessel, picking up speed by shallow diving. The whale rammed the ship and then went under, battering it and causing it to tip from side to side. Finally surfacing close on the [[starboard]] side of ''Essex'' with its head by the [[Bow (ship)|bow]] and [[tail]] by the stern, the whale appeared to be stunned and motionless. Chase prepared to [[harpoon]] it from the deck when he realized that its tail was only inches from the [[rudder]], which the whale could easily destroy if provoked by an attempt to kill it. Fearing to leave the ship stuck thousands of miles from land with no way to steer it, he relented. The whale recovered and swam several hundred yards ahead of the ship and turned to face the bow. |

||

<blockquote>"I turned around and saw him about one hundred rods [550 yards] directly ahead of us, coming down with twice his ordinary speed [around 24 |

<blockquote>"I turned around and saw him about one hundred rods [500 m or 550 yards] directly ahead of us, coming down with twice his ordinary speed [around {{convert|24|kn|km/h}}, and it appeared with tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect. The surf flew in all directions about him with the continual violent thrashing of his tail. His head about half out of the water, and in that way he came upon us, and again struck the ship." —Owen Chase.<ref> Chase(1821) p. 26</ref></blockquote> |

||

The whale crushed the bow like an eggshell, driving the 238-ton vessel backwards. The whale finally disengaged its head from the shattered [[timber]]s and swam off, never to be seen again, leaving the ''Essex'' quickly going down by the bow. Chase and the remaining sailors frantically tried to add [[rigging]] to the only remaining whaleboat, while the steward ran below to gather up whatever navigational aids he could find. |

The whale crushed the bow like an eggshell, driving the 238-ton vessel backwards. The whale finally disengaged its head from the shattered [[timber]]s and swam off, never to be seen again, leaving the ''Essex'' quickly going down by the bow. Chase and the remaining sailors frantically tried to add [[rigging]] to the only remaining whaleboat, while the steward ran below to gather up whatever navigational aids he could find. |

||

Revision as of 02:44, 20 November 2013

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Essex |

| Laid down | Nantucket, Massachusetts |

| Fate | Struck by a sperm whale and sunk, 20 Nov., 1820 |

| Notes | Sunk 0° 4' 0" S latitude, 119° 0' 0" W longitude |

| General characteristics | |

| Tons burthen | 238 tons |

| Length | 87 feet (27 m) long |

| Notes | Four whaleboats, 20–30 ft long |

|

Crew of Essex |

|

Captain Matthew Joy † Thomas Chappel William Bond † Sailors Owen Coffin † *deserted in Ecuador, Sept 1820 |

Essex was an American whaleship from Nantucket, Massachusetts. The ship, captained by George Pollard, Jr., was widely known for being attacked and sunk by a sperm whale in the southern Pacific Ocean in 1820 – an incident that served as inspiration for Herman Melville's 1851 novel, Moby-Dick.

Ship and crew

Essex was an elderly ship, but because so many of her voyages were profitable she gained the reputation as a “lucky” vessel. Captain George Pollard and his first mate, Owen Chase, had served together on her previous, equally successful, trip, and it led to their promotions. Only 29, Pollard was one of the youngest men ever to command a whaling ship. Owen Chase was 23, and the youngest member of the crew was the cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson, who was 14.

She had recently been totally refitted, but at 87 feet (27 m) long, and measuring 238 tons,[1] she was small for a whaleship. Essex was equipped with four separate whaleboats, each about {{convert|28|ft|m|abbr=on} in length, which were launched from the ship. In addition, a spare was kept below decks.[2] These boats were built for speed rather than durability, being Clinker built, with planks that overlapped each other rather than fitting flush together.[3]

Voyage

Essex left Nantucket on August 12, 1819 on a two-and-a-half-year voyage to the whaling grounds off the west coast of South America. Two days after leaving port the ship was hit by a squall that knocked her on her beam ends, nearly sinking her. The topgallant sail was lost, with one whaleboat damaged and two destroyed. Deciding to continue without replacing the boats and repairing the damage, Essex rounded Cape Horn in January 1820. This passage took a full five weeks, which was extreme even for that time; combined with the unsettling earlier incident there began to be talk of ill-omens. This was put aside as Essex began the long spring and summer hunt in the warm waters of the south Pacific, going up the western coast of South America.

Finding the area nearly fished out, they encountered other whalers, who told them of a newly discovered hunting ground, known as the "offshore ground", located at 5–10 degrees south latitude and 105–125 degrees west longitude, in the South Pacific, roughly 2500 nautical miles (4,600 km) to the south and west. In the early days of Pacific whaling, this was an immense distance to travel out from land, and the area, with its many islands rumored to be populated by cannibals, was an unknown quantity. To restock their food supplies for the long journey, Essex sailed for Charles Island in the Galapagos Islands group.

Due to the need to fix a serious leak, the vessel first anchored at Hood Island on October 8. Over seven days they captured 300 Galápagos giant tortoises to supplement the ship's stores. They then sailed for Charles Island where on October 22 they obtained another 60 tortoises.[4] While hunting on Charles Island, helmsman Thomas Chappel decided to set a fire as a prank. Being the height of the dry season, the fire soon burned out of control and quickly surrounded the hunters, who were forced to run through the flames to escape. By the time the men returned to Essex almost the entire island was burning. The crew were upset about the fire and Captain Pollard swore vengeance on whomever had set it. Fearing a whipping, it was to be some time before Chappel admitted to being the culprit. The next day saw the island still burning as the ship sailed for the offshore grounds and after a full day of sailing the fire was still visible on the horizon. Many years later Nickerson returned to Charles Island and found a black wasteland, "neither trees, shrubbery, nor grass have since appeared." It is believed the fire contributed to the extinction of the Floreana Tortoise and the Floreana Mockingbird.[5]

Whale attack

Thousands of miles from the coast of South America, tension was mounting among the officers of Essex, in particular between Pollard and Chase. The launched whaleboats had come up empty for days, and on November 16, Chase's boat had been "dashed...literally in pieces" by a whale surfacing directly beneath it. But at eight in the morning of November 20, 1820, the lookout sighted spouts and the three remaining whaleboats set out to pursue a sperm whale pod.[6]

On the leeward side of Essex Chase's boat harpooned a whale, but its fluke struck the boat and opened up a seam, resulting in their having to cut his line from the whale and put back to the ship for repairs. Two miles away off the windward side, Captain Pollard and the second mate's boats had each harpooned a whale and were being dragged towards the horizon in what was known as a Nantucket sleighride. Chase was repairing the damaged boat on board when the crew observed a whale, that was much larger than normal (alleged to be around 85 feet (26 m)), acting strangely. It lay motionless on the surface with its head facing the ship, then began to move towards the vessel, picking up speed by shallow diving. The whale rammed the ship and then went under, battering it and causing it to tip from side to side. Finally surfacing close on the starboard side of Essex with its head by the bow and tail by the stern, the whale appeared to be stunned and motionless. Chase prepared to harpoon it from the deck when he realized that its tail was only inches from the rudder, which the whale could easily destroy if provoked by an attempt to kill it. Fearing to leave the ship stuck thousands of miles from land with no way to steer it, he relented. The whale recovered and swam several hundred yards ahead of the ship and turned to face the bow.

"I turned around and saw him about one hundred rods [500 m or 550 yards] directly ahead of us, coming down with twice his ordinary speed [around 24 knots (44 km/h), and it appeared with tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect. The surf flew in all directions about him with the continual violent thrashing of his tail. His head about half out of the water, and in that way he came upon us, and again struck the ship." —Owen Chase.[7]

The whale crushed the bow like an eggshell, driving the 238-ton vessel backwards. The whale finally disengaged its head from the shattered timbers and swam off, never to be seen again, leaving the Essex quickly going down by the bow. Chase and the remaining sailors frantically tried to add rigging to the only remaining whaleboat, while the steward ran below to gather up whatever navigational aids he could find.

"The captain's boat was the first that reached us. He stopped about a boat's length off, but had no power to utter a single syllable; he was so completely overpowered with the spectacle before him. He was in a short time, however, enabled to address the inquiry to me, "My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?" I answered, "We have been stove by a whale." —Owen Chase.

Survivors

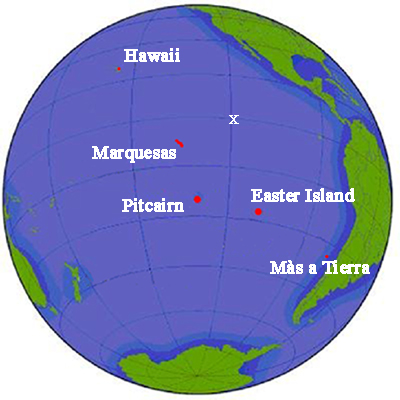

The ship sank 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 km) west of South America. After spending two days salvaging what supplies they could, the twenty sailors set out in the three small whaleboats with wholly inadequate supplies of food and fresh water. The closest known islands, the Marquesas, were more than 1,200 mi (1,900 km) to the west and Captain Pollard intended to make for them but the crew, led by Owen Chase, feared the islands might be inhabited by cannibals and voted to make for South America. Unable to sail against the Trade winds, the boats would need to sail south for 1,000 mi (1,600 km) before they could use the Westerlies to turn towards South America, which would still lie another 3,000 mi (4,800 km) to the east.

Food and water was rationed from the beginning, but most of the food had been soaked in seawater and this was eaten first despite it increasing their thirst. It took around two weeks to consume the contaminated food and by this time the survivors were rinsing their mouths with seawater and drinking their own urine. Never designed for long voyages, all the whaleboats had been roughly repaired and leaks were a constant and serious problem. After losing a timber, the crew of one boat had to lean to one side to raise the other side out of the water; however, another boat was able to draw close and a sailor nailed a piece of wood over the hole. Literally within hours of the crew beginning to die of thirst, the boats landed on uninhabited Henderson Island, within the modern-day British territory of the Pitcairn Islands. Had they landed on Pitcairn, 104 miles (167 km) to the S/W, they would have received help; it was habitable and the survivors of HMS Bounty still lived there. On Henderson Island they found a small freshwater spring and the men gorged on birds, eggs, crabs, and peppergrass. However, after one week, they had largely exhausted the island's food resources and on December 26 concluded that they would starve if they remained much longer. Three men, William Wright, Seth Weeks and Thomas Chappel, who were the only white members of the crew who were not natives of Nantucket, opted to stay behind on Henderson, and the remaining Essex crewmen resumed the journey on 27 December, hoping to reach Easter Island. Within three days they had exhausted the crabs and birds they had collected for the voyage, leaving only a small reserve of bread, salvaged from Essex. On January 4, they estimated that they had drifted too far south of Easter Island to reach it and decided to make for Más a Tierra island, 1,818 miles (2,926 km) to the east and 419 miles (674 km) west of South America. One by one, the men began to die.[8]

Chase boat

On January 10, Matthew Joy died and on the following day the boat carrying Owen Chase, Richard Peterson, Isaac Cole, Benjamin Lawrence and Thomas Nickerson became separated from the others during a squall. Peterson died on January 18 and like Joy, was sewn into his clothes and buried at sea, as was the custom. On February 8, Isaac Cole died but with food running out they kept his body and, after a discussion, the men resorted to cannibalism in order to survive. By February 15 the three remaining men had again run out of food and on February 18, were spotted and rescued by the British whaleship Indian, 90 days after the sinking of the Essex. Several days after the rescue, Chase's whaleboat was lost in a storm while under tow behind the Indian.[9]

Pollard and Hendricks boats

Obed Hendricks's boat exhausted their food supplies on January 14 with Pollard's men exhausting theirs on January 21. Lawson Thomas had died on January 20 and it was now decided they had no choice but to keep the body for food. Charles Shorter died on January 23, Isaiah Shepard on January 27 and Samuel Reed on January 28. Later that day the two boats separated with the one carrying Obed Hendricks, Joseph West and William Bond never to be seen again.

By February 1 the food had run out and the situation in Captain Pollard's boat became quite critical. The men drew lots to determine who would be sacrificed for the survival of the crew. A young man named Owen Coffin, Captain Pollard's 17-year old cousin, whom he had sworn to protect, drew the black spot. Pollard allegedly offered to protect his cousin but Coffin is said to have replied "No, I like my lot as well as any other." Lots were drawn again to determine who would be Coffin's executioner. His young friend, Charles Ramsdell, drew the black spot. Ramsdell shot Coffin, and his remains were consumed by Pollard, Barzillai Ray, and Charles Ramsdell. On February 11, Ray also died. For the remainder of their journey, Pollard and Ramsdell survived by gnawing on the bones of Coffin and Ray. They were rescued when almost within sight of the South American coast by the Nantucket whaleship Dauphin, on February 23, 95 days after Essex sank. Both men by that time were so completely dissociative that they did not even notice the Dauphin alongside them and became terrified by seeing their rescuers.

Rescue and reunion

After a few days in Valparaíso, Chase, Lawrence and Nickerson were transferred to the U.S. frigate USS Constellation and placed under the care of the ship’s doctor who oversaw their recovery. After officials were informed that three Essex survivors were stranded on Henderson Island, an Australian trader destined on a trans-Pacific passage was ordered to look for the men. Although close to death, the three men were eventually rescued.[9]

On 17 March, Pollard and Ramsdell were reunited with Chase, Lawrence and Nickerson. By the time the last of the eight survivors were rescued on April 5, 1821 the corpses of seven fellow sailors had been consumed. All eight returned to the sea within months of their return to Nantucket. Herman Melville later speculated that all would have survived had they followed Captain Pollard's recommendation and sailed west.[10]

Aftermath

Several years later, a whaleboat containing four skeletons was found beached on a Pacific island. Although it was suspected to be Obed Hendricks's missing boat the remains were never positively identified.[9]

Captain George Pollard, Jr. returned to sea in early 1822 to captain the whaleship Two Brothers. After it was wrecked on the French Frigate Shoals during a storm off the coast of Hawaii on his first voyage, he joined a merchant vessel which was in turn also wrecked off the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands) shortly after. By now he was considered a "Jonah" (unlucky), and no ship owner would trust him to sail on a ship again, so he was forced to retire. He became Nantucket's night watchman. Every November 20, he would lock himself in his room and fast in memory of the men of Essex.[8]

First Mate Owen Chase returned to Nantucket on June 11, 1821 to find he had a 14-month-old daughter he had never seen. Four months later he had completed an account of the disaster, the Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex; this was used by Herman Melville as one of the inspirations for his novel Moby-Dick. In December he sailed as first mate on the whaler Florida and then as captain of Winslow for each subsequent voyage until he had his own whaler, Charles Carrol, built. Chase remained at sea for 19 years, only returning home for short periods every two or three years, each time fathering a child. His first two wives died while he was at sea. He divorced his third wife when he found she had given birth 16 months after he had last seen her, although he subsequently brought up the child as his own. In September 1840, two months after the divorce was finalised, he married for the fourth and final time and retired from whaling.[8] Memories of the harrowing ordeal haunted Chase, and he suffered terrible headaches and nightmares. Later in his life, he began hiding food in the attic of his Nantucket house on Orange Street and was eventually institutionalized.[11]

The cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson, became a captain in the Merchant Service and later wrote another account of the sinking titled The Loss of the Ship "Essex" Sunk by a Whale and the Ordeal of the Crew in Open Boats which was not published until 1984 by the Nantucket Historical Association. Nickerson wrote his account late in his life and it was lost until 1960. It was not until 1980, when it came into the hands of Nantucket whaling expert Edouard Stackpole, that its significance was realized.

Charles Ramsdell captained the whaleship General Jackson before his retirement. Benjamin Lawrence went on to captain the whaleships Dromo and Huron before retiring to become a farmer. William Wright returned to whaling and drowned during a hurricane in the West Indies. Seth Weeks retired to Cape Cod. Thomas Chappel is believed to have become a missionary preacher.

Most of the survivors at some time or another wrote accounts of the disaster, some of which differ considerably on details regarding the behavior of various survivors.

While Essex was the first ship sunk by a whale, it was not the last. In 1835, Pusie Hall was attacked. In 1836, Lydia and Two Generals were both attacked by whales. Pocahontas was sunk by a whale in 1850 as was Ann Alexander the following year.

Legacy

As noted above, word of the sinking reached a young Herman Melville when, while serving on the whaleship Acushnet, he met the son of Owen Chase who was serving on another whaleship. Coincidentally, the two ships encountered each other less than 100 mi (160 km) from where Essex sank. Chase lent his father's account of the ordeal to Melville, who read it at sea and was inspired by the idea that a whale was capable of such violence. Melville later met Captain Pollard, writing inside his copy of Chase's narrative, "Met Captain Pollard on Nantucket. To most islanders a nobody. To me, one of the most extraordinary men I have ever met." In time, he wrote Moby-Dick: or, The Whale, in which a sperm whale is said to be capable of similar acts. Melville's book draws its inspiration from the first part of the Essex story, ending with the sinking.

See also

- Ann Alexander, a ship sunk by a whale on August 20, 1851

- In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, a National Book Award-winning work of maritime history by Nathaniel Philbrick telling the Essex story from the point of view of both Nickerson and Chase.

- Custom of the Sea

- R v Dudley and Stephens

- The Raft of the Medusa

- The Divinity of Oceans, an album conceptually based upon these events by German funeral doom band, Ahab

References

- ^ Philbrick 2001, p. 241, citing original 1799 specifications.

- ^ Chase (1965), p. 19

- ^ The Wreck of the Whaleship Essex BBC

- ^ Weighing between 100 pounds (45 kg) and 800 pounds (360 kg) each, the tortoises were kept alive and allowed to roam the ship at will. They could live for around a year without the need to be fed or given water. Considered delicious and extremely nutritious by sailors they were butchered for food as the need arose.

- ^ Account of the Ship Essex Sinking, 1819–1821 Thomas Nickerson

- ^ Chase (1965), p. 30

- ^ Chase(1821) p. 26

- ^ a b c Edward Leslie & Sterling Seagrave Desperate Journeys, Abandoned Souls: True Stories of Castaways and Other Survivors Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 1998 pg 251 – 253 ISBN 978-0-395-91150-1

- ^ a b c Surviving the Essex Disaster (Part 3 of 3) Providencia December 2, 2012

- ^ Gussow, Mel (1 August 2000). "Resurrecting The Tale That Inspired and Sank Melville". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

Melville wrote in his annotations on his copy of Chase's Narrative: 'All the sufferings of these miserable men of the Essex might, in all human probability, have been avoided had they immediately after leaving the wreck, steered straight for Tahiti, from which they were not very distant at the time. But they dreaded cannibals.' Melville knew that missionaries had been on the island and that it was safe.

- ^ Philbrick 2001, p. 244.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2001). In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-100182-8. OCLC 46949818.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chase, Owen (1965). Iola Haverstick, Betty Shepard (ed.). The Wreck of the Whaleship Essex. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. p. 124.

Further reading

- Chase, Owen (1821). Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex. New York: W. B. Gilley. OCLC 12217894. Also in Heffernan, Thomas Farel, Stove by a whale: Owen Chase and the Essex, Middletown, Conn. : Wesleyan University Press ; [New York] : distributed by Columbia University Press, 1981.

- Nickerson, Thomas (1984) [1876]. The Loss of the Ship Essex Sunk by a Whale and the Ordeal of the Crew in Open Boats. Nantucket: Nantucket Historical Society. OCLC 11613950.

- Karp, Walter, "The Essex Disaster", American Heritage, April/May 1983 (34:3)

External links

- Summary of the Essex Tragedy

- Artifacts of the Essex

- Nantucket Historical Association

- Nantucket Whaling Museum

- "Into the Deep: America, Whaling & the World", PBS, American Experience, 2010.

- 'Moby Dick' captain's ship found — George Pollard, Jr.

- The Drawing of the Whale That Became Moby Dick on Atlas Obscura