Affirmative action

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court reversed lower court decisions in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, effectively ending the use of affirmative action in college admissions. This article does not receive scheduled updates. If you have any questions or comments, contact us.

Affirmative action refers to a set of policies adopted by governments and institutions to take proactive measures to increase the proportion of historically disadvantaged minority groups. These measures have taken many different forms, including strict quotas, extra outreach efforts and student financial aid specifically for minorities. In the decades since it was first instituted, affirmative action has often taken the form of racial preferences.

Originally focused on racial minorities, affirmative action policies were later expanded to include preferences for women as well. Affirmative action policies can most often be found in government employment and university admissions. University admissions policies, in particular, have come under increasing scrutiny for their reliance on racial preferences to achieve diversity. Polls have shown that while there is general support for affirmative action, support drops considerably when the question mentions preferences.

While some studies have shown that ending the use of racial preferences in admissions lowers minority enrollment at the most selective institutions, others show that doing so does not affect minority college enrollment overall and increases graduation rates. Such studies, in conjunction with changing court rulings over the past two decades on the legality of some affirmative action policies, have created uncertainty regarding the goals of these policies and how best to implement them.

Current debate on affirmative action includes the following issues:

- the use and legality of racial preferences

- the efficacy of a shift to socioeconomic preferences

- the gap in student preparation between minority and white students in K-12 public education

As of February 2015, eight states had banned the use of racial preferences in public employment, public university admissions and government contracting.

On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court reversed lower court decisions in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, effectively ending the use of affirmative action in college admissions.

Background

The first reference to affirmative action was made by President John F. Kennedy (D) in 1961 in an executive order directing government contractors to take "affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin." The order also established the agency that became the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), a federal agency that investigates claims of workplace discrimination. This move was significant: while the federal government had made previous efforts to end racial discrimination, they had been largely preventative; this order marked the first instance of an active approach to equal opportunity.[1][2][3][4]

As the civil rights movement of the 1960s expanded, the federal government took on an increasing role in preventing discrimination and bolstering minority numbers in workplaces and universities. President Lyndon Johnson (D) signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964, a landmark piece of legislation that prohibited discrimination against any individual based on his or her race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Central to the legislation were Title VI, which prohibits discrimination by agencies that receive federal funding, and Title VII, which prohibits discrimination in employment and contains the disparate impact clause. However, some still felt that discrimination prevention was not enough:[1][5][6]

| “ |

Affirmative action policies initially focused on improving opportunities for African Americans in employment and education. The Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 outlawing school segregation and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 improved life prospects for African Americans. In 1965, however, only five percent of undergraduate students, one percent of law students, and two percent of medical students in the country were African American. President Lyndon Johnson, an advocate for affirmative action, signed an Executive Order in 1965 that required government contractors to use affirmative action policies in their hiring to increase the number of minority employees.[7] |

” |

| —National Conference of State Legislatures | ||

Johnson's order created the means for enforcing affirmative action policies for the first time, with the threat of sanctions for noncompliance; the order was later expanded to include discrimination against women. Of their own initiative, many colleges and universities nationwide also adopted affirmative action policies to increase minority enrollment. These policies usually took the form of preferences in admissions for applicants of a minority race, although some colleges generated strict quotas or reserved a specific number of spots for minorities.[3][4]

The use of affirmative action in all of these areas was initially intended to be temporary. However, the goals of affirmative action policies shifted from equality of opportunity to the achievement of equal representation and outcomes for minorities at all levels of society. Furthermore, lawsuits have been brought against institutions utilizing affirmative action policies, citing violations of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Titles VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act. In Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court ruled that promoting diversity, rather than compensating for historical injustices, was the constitutional goal of affirmative action. The court also placed the burden on universities to prove that no viable race-neutral alternatives existed when they used racial preferences in admissions to increase diversity.[1][2][8]

In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, the Supreme Court effectively ended race-based considerations in college admissions in a June 29, 2023, decision. The ruling explicitly allowed national service academies to continue considering race as a factor in admissions for reasons of national security.[9][10]

Major court cases

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 1978

The first major legal challenge to affirmative action policies was brought in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. Allan Bakke, a white male, brought suit against the University of California (UC) for twice denying him entrance to the medical school, claiming he was excluded on the basis of race. The university reserved 16 of 100 spots for minority applicants and had admitted minorities with lower qualifications than Bakke. The United States Supreme Court found that universities could consider race as one factor to achieve a diverse student body, but it struck down the strict quotas UC had utilized as discriminatory toward white applicants. It also noted that in addition to remedying past discrimination, diversity was a legitimate goal, or "compelling governmental interest," of affirmative action. The decision broadly expanded and legitimized affirmative action while attempting to minimize opposition to perceived injustice against white students.[3][4][11][12]

Hopwood v. University of Texas Law School, 1996

Although strict quotas were no longer used, universities continued to consider race in the form of preferences for minority candidates. Cheryl Hopwood and three other white students challenged the use of racial preferences in admissions in Hopwood v. Texas after they were rejected from the University of Texas Law School. The 5th U.S. Court of Appeals found in favor of Hopwood, rendering the 1978 Bakke decision invalid by ruling that diversity was actually "not recognized as a compelling state interest" and suspending the affirmative action program of the University of Texas. The U.S. Supreme Court let the ruling stand, and soon after, all public universities in Texas switched to race-blind admissions. The ruling also affected affirmative action admissions in Louisiana and Mississippi.[3][13]

Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger, 2003

Two cases against the University of Michigan were heard in conjunction by the Supreme Court: Gratz v. Bollinger against the university's undergraduate admissions, and Grutter v. Bollinger against the University of Michigan Law School. Jennifer Gratz and Barbara Grutter were both white students who had been rejected from the University of Michigan, Gratz from the undergraduate program and Grutter from the law school. Lee Bollinger, president of university at the time, served as the defendant, arguing that the programs served the legitimate purpose of campus diversity. The court struck down the "mechanical" points system of the undergraduate school, which awarded 20 extra points—one-fifth of the total needed for admission—to applicants of a minority race, ruling that the system was not "narrowly tailored" and violated the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the court upheld the policy of the law school, stating that the consideration of race in its admissions was "highly individualized" and consistent with the ruling in Bakke. The Grutter decision invalidated the finding of the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals in Hopwood.[3][14][15]

Parents v. Seattle and Meredith v. Jefferson, 2006

Parents v. Seattle and Meredith v. Jefferson, two cases that were heard in conjunction, challenged for the first time the consideration of race in public school assignments. Both Seattle School District Number 1 and Jefferson County Public Schools allowed students to apply to any school in the district. When demand for a particular school exceeded available space, the students' race was considered along with other factors to determine enrollment. Lower courts had applied the precedents set in Grutter and Gratz to determine if the schools' systems served a "compelling government interest" and were "narrowly tailored" to achieve that interest. They found that the policies were lawful and consistent with previous interpretations of the law by the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court ruled that the decision in Grutter v. Bollinger did not apply to high schools and that the programs were not narrowly tailored. The court found that both districts' plans were "actually targeted toward demographic goals and not toward any demonstrable educational benefit from racial diversity." The ruling restricted the use of affirmative action in public schools.[3][16][17][18]

Ricci v. DeStefano, 2009

In 2003 the city of New Haven, Connecticut administered civil service exams to firefighters in order to make selections for promotion to lieutenant and captain. A disproportionate number of white candidates, compared to minority candidates, earned high enough scores on the test to qualify for promotion. The city chose to discard the results of the test for fear of being liable under the disparate impact clause of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In Ricci v. DeStefano a group of firefighters headed by Frank Ricci, 17 white and one Hispanic, who had qualified for promotion brought suit against the city and Mayor John DeStefano for violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and for discrimination prohibited by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. The Supreme Court found in favor of the firefighters, writing that the city had intentionally discriminated against the firefighters who had passed the test without providing a "strong basis in evidence" that the discrimination was necessary to avoid disparate impact. However, the court avoided commenting on the discrepancy between the disparate impact provision of Title VII and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[19]

Fisher v. University of Texas, 2013

After the Hopwood decision, the University of Texas (UT) adopted a policy of automatically admitting high school students who graduated in the top 10 percent of their class. It later revised this policy to allow the consideration of race for those who were not automatically admitted. After Abigail N. Fisher, a white female, was denied admission to UT-Austin, she challenged the university's consideration of race as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in Fisher v. University of Texas. In its ruling, the Supreme Court found faults in the decision by the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals. The court stated that affirmative actions cases should be reviewed under the Fourteenth Amendment according to "a standard of strict scrutiny," which the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals did not do. The opinion went on to say that universities must be able to show that "available, workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice." The case was sent back to the 5th U.S. Court of Appeals for further review, where UT-Austin's admissions policy was ultimately upheld. However, the ruling placed the burden on universities to prove that racial diversity could not be achieved via any other method when they utilize racial preferences.[3][20]

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, 2023

In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, two cases that were heard in combination, plaintiffs asked the Supreme Court to overturn the precedent established in Grutter v. Bollinger that "student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions." [21] According to its website, Students for Fair Admission (SFFA) described its mission as: "to support and participate in litigation that will restore the original principles of our nation’s civil rights movement: A student’s race and ethnicity should not be factors that either harm or help that student to gain admission to a competitive university."[22]

In a 6-3 decision, the court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, significantly limiting the consideration of race in college admissions. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts wrote that "the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race. Many universities have for too long done just the opposite. And in doing so, they have concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin."[9]

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Sotomayor wrote that, in ruling in favor of the plaintiffs, "the Court cements a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter. The Court subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education, the very foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society."[9]

In deciding the case, the court reversed the decisions of lower federal courts that upheld both Harvard and the University of North Carolina's admission standards. According to Susan Howe of SCOTUS Blog, in doing so, the court "severely limited, if not effectively ended, the use of affirmative action in college admissions" and "effectively, though not explicitly, overruled its 2003" decision in Grutter. [23] The only institutions of higher education explicitly exempted from the ruling were the nation's military academies.[10]

Public opinion

Public opinion polls on affirmative action have yielded mixed results over the past few years. Results found by researchers seem to depend largely on how the question is worded. In particular, support drops considerably when the word "preferences" is included in the question. Supporters of affirmative action are more likely to do so to increase diversity rather than compensate for past injustice.[24][25]

Opinions also change when the question refers to college admissions specifically, and support and opposition are somewhat divided on racial lines, with black Americans being far more likely to favor affirmative action. According to Gallup:[26][27]

| “ |

One of the clearest examples of affirmative action in practice is colleges' taking into account a person's racial or ethnic background when deciding which applicants will be admitted. Americans seem reluctant to endorse such a practice, and even blacks, who have historically been helped by such programs, are divided on the matter.[7] |

” |

| —Gallup | ||

However, in 2007 a poll by Pew Research Center found that 82 percent of Americans reported feeling completely unaffected by affirmative action. A previous study by Pew Research Center in 2002 had found a similar result, with only 16 percent reporting having been affected; 11 percent said they'd been hurt by affirmative action, and only 4 percent felt they had been helped.[27]

In general, support for affirmative action has dropped since its peak in the early 1990s, when a poll by NBC News/Wall Street Journal found that 61 percent of Americans thought that affirmative action policies were still needed, compared to 45 percent in June 2013. The table below lists the results of several polls taken on affirmative action over the past 15 years.[28]

| Public opinion polls on affirmative action | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poll | Year | Question | Response | ||

| Pew | 2002 | "In order to overcome past discrimination, do you favor or oppose affirmative action programs..." | "designed to help blacks, women and other minorities get better jobs and education?" | Favor: 63% | Oppose: 29% |

| "which give special preferences to qualified blacks, women and other minorities in hiring and education?" | Favor: 57% | Oppose: 35% | |||

| "All in all, do you think affirmative action programs designed to increase the number of black and minority students on campus on college campuses..." | "are a good or bad thing?" | Good: 60% | Bad: 30% | ||

| "are fair or unfair?" | Fair: 47% | Unfair: 42% | |||

| "We should make every possible effort to improve the position of blacks and other minorities, even if it means giving them preferential treatment." | Agree: 24% | Disagree: 72% | |||

| Pew | 2007 | "In order to overcome past discrimination, do you favor or oppose affirmative action programs designed to help blacks get better jobs and education?" | Support: 60% | ||

| "In order to overcome past discrimination, do you favor or oppose affirmative action programs, which give special preferences to qualified blacks in hiring and education?" | Support: 42% | ||||

| Gallup | 2013 | "Do you generally favor or oppose affirmative action programs for racial minorities?" | Favor: 58% | Oppose: 37% | |

| "Which comes closer to your view about evaluating students for admission into a college or university -- [ROTATED: applicants should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in fewer minority students being admitted (or) an applicant's racial and ethnic background should be considered to help promote diversity on college campuses, even if that means admitting some minority students who otherwise would not be admitted]?" | Consider race: 28% | Solely on merit: 67% | |||

| CBS News/NYT | 2013 | "Do You Favor or Oppose Affirmative Action Programs for Minorities?" | Favor: 53% | Oppose: 38% | |

| NBC News/WSJ | 2013 | "Is affirmative action still needed, or should it be ended?" | Needed: 45% | Ended: 45% | |

| Pew | 2014 | "In general, do you think affirmative action programs designed to increase the number of black and minority students on college campuses are a good thing or a bad thing?" | Good: 63% | Bad: 30% | |

Support

Common reasons stated for supporting affirmative action include the following:[1][29]

- Diversity is valuable for any workplace or college campus.

- Minority enrollment in college would fall dramatically without affirmative action.

- Affirmative action provides the extra push to disadvantaged students that is needed to succeed.

- By providing minorities with new opportunities, affirmative action may introduce them to other interests they would not have discovered otherwise.

- Affirmative action is necessary to break stereotypes.

- Affirmative action compensates for past injustices.

Organizations supporting affirmative action

- "We support affirmative action and other race- and gender-conscious policies as vital tools in the struggle to provide all Americans with equal opportunity, to promote diversity in academic and professional settings, and to give each and every one of us a fair chance to compete."[30]

- "Affirmative Action levels the playing field so people of color and all women have the chance to compete in education and in business."[30]

Opposition

Common arguments stated against affirmative action include the following:[29]

- Affirmative action policies have caused "reverse discrimination" against whites.

- According to the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, affirmative action is unconstitutional.

- Since standards are lowered by preferential treatment, minorities only aim for those lower standards.

- Affirmative action causes a "mismatch effect" of underqualified students, leading to their failure at elite schools.

- Affirmative action is demeaning and condescending to minority achievement.

- It is too difficult to end affirmative action policies after they have been enacted, even when discrimination is no longer an issue.

Organizations and individuals opposing affirmative action

- "In my view, using the powers of government to make sure that people are not discriminated against, I think that was the original intent of affirmative action. I think that is legitimate. ... But when it gets to the point where you are making a selection for someone to be admitted to the university or someone to be hired for a job, and to have one standard for someone who is black and another standard for someone who is white ... that's discriminatory."[31]

- Center for Individual Rights (CIR)

- "CIR's civil rights cases are designed to get the government out of the business of granting preferential treatment to members of favored racial groups. Just as the First Amendment prohibits the government from favoring the expression of certain points of view, the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the government from enforcing its laws, rules, and polices differently solely on account of the race of an individual."[32]

Studies

Enrollment

- See also: Higher education enrollment statistics

Supporters of affirmative action in college admissions have voiced concern over projected drops in minority college enrollment in the event of bans on racial preferences. Studies have shown that affirmative action bans do not affect minority college enrollment in a state overall, although they do seem to lower minority enrollment at the most selective institutions. It is important to note here that most colleges in the United States are not very selective; colleges considered very selective make up about one-fifth to one-fourth of all four-year colleges in the country.[33][34][35]

The New York Times

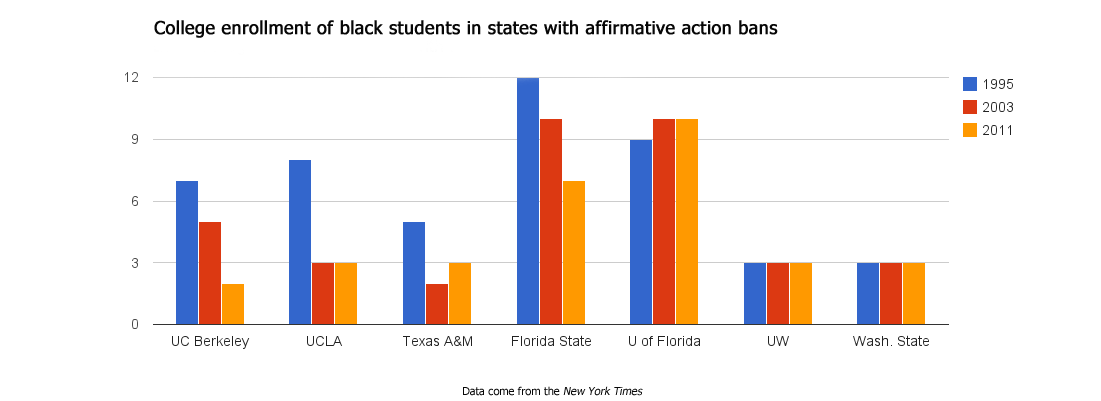

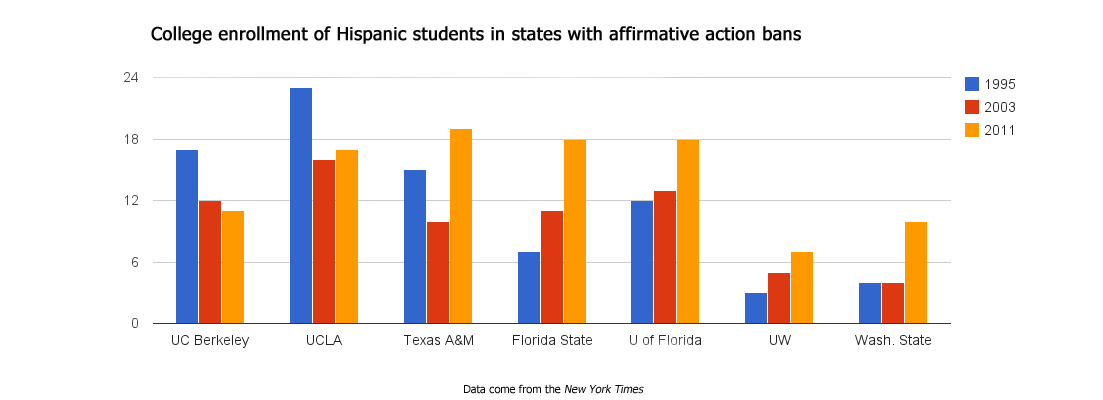

The New York Times published data in 2014 on minority enrollment at selective universities in states that had enacted bans on racial preferences. The newspaper looked at data from the National Center for Education Statistics and concluded that it showed a trend of lower minority enrollment at selective institutions after bans on racial preferences went into effect. The following charts show black and Hispanic college enrollment as percentages in select years from 1995 to 2011 in states with bans on racial preferences using data reported by The New York Times. California banned racial preferences in 1998, Texas banned them in 1997, Florida banned them in 2001, and Washington banned them in 1999.[36]

The Century Foundation

Looking at similar data, a study from The Century Foundation examined minority enrollment at 11 flagship universities that had ended the use of racial preferences in university admissions:

- University of Texas at Austin

- Texas A&M

- University of California, Berkeley

- University of California, Los Angeles

- University of Washington

- University of Florida

- University of Georgia

- University of Michigan

- University of Nebraska

- University of Arizona

- University of New Hampshire

The study, released in 2014, focused on the percentage of black and Hispanic students at each institution before and after the ban on racial preferences. The analysis found that seven of these institutions managed to either reach or exceed minority enrollment levels present the year before the ban on racial preferences. Only two institutions, UC Berkeley and UCLA, failed to recruit the same levels of both blacks and Hispanics. The other two universities, University of Michigan and University of New Hampshire, admitted the same percentage or higher of Hispanic students, but not black students.[37]

Mismatch

| Graduation rates by race/ethnicity, 2010 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | Students in class | Graduate in 4 years | Percent | Graduate in 6 years | Percent |

| Asian | 55,653 | 21,132 | 38% | 36,876 | 66.3% |

| American Indian | 7,378 | 1,270 | 17.2% | 2,728 | 37% |

| Black | 93,126 | 15,246 | 16.4% | 35,710 | 38.3% |

| Hispanic | 62,240 | 13,371 | 21.5% | 29,770 | 47.8% |

| White | 570,146 | 194,873 | 34.2% | 335,792 | 58.9% |

| Total | 830,151 | 259,874 | 31.3% | 464,881 | 56% |

| Source: The Chronicle of Higher Education, "College Completion: Who graduates from college, who doesn't, and why it matters." accessed February 23, 2015 | |||||

The table above shows 2010 graduation rates at public four-year colleges by race/ethnicity. Studies have shown that while black students are more likely to enroll in college than white students with similar credentials, they are less likely to graduate. Lower graduation rates can also be seen for other underrepresented minorities such as Hispanics and American Indians. Minorities that do graduate have been found more likely to finish at the bottom of their class. Thomas J. Espenshade, co-author of No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal, looked at data from eight elite institutions and found that 50 percent of black students and "one-third of Hispanic students graduated in the bottom 20 percent of their class."[38]

This gap in performance at institutions of higher learning has puzzled and concerned scholars and policymakers for decades. One theory that attempts to explain it is the "mismatch effect." According to the theory, the lower performance of underrepresented minorities is due to their admission by racial preferences into selective universities despite academic credentials below those of their peers. It has been shown through studying the SAT scores of students at selective universities that a preference can act as a 150- to 350-point adjustment to the student's SAT score, granting admission to a minority student with much lower SAT scores than other admitted students. The theory contends that these minorities would have a higher chance of success at an institution where their credentials more closely matched those of the majority on campus. Since the development of the theory, numerous studies have been performed to attempt to prove or disprove the mismatch effect. It is unclear what effects mismatch would have, if any, on minority success later in life.[35][39][40]

| Proposition 209 |

|---|

| California became the first state to ban racial preferences in university admissions when voters approved Proposition 209 in 1996. Furthermore, the University of California (UC) system contains two elite universities, UC Berkeley and UCLA, where mismatch theorists such as Richard Sander say large racial preferences were used before the ban. For this reason, studies regarding affirmative action and mismatch tend to focus on the effects of the Prop 209 on the University of California system. |

Evidence of mismatch

In 2012, mismatch theorists Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor penned the book Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It's Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won't Admit It, which explored evidence found by Sander and other researchers that the mismatch effect harms minority benefactors of affirmative action. Such studies have found that mismatch can have an unintended negative effect on the college experience of minorities, from influencing area of study to fostering racial stereotypes on campus. In a 2005 study, Sander found that mismatch doubled the rate of minority bar exam failures, and other researchers have found that mismatch is responsible for the low number of minorities pursuing STEM majors, as well as choosing to become professors.[35][41]

A 2012 working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) found that after California banned racial preferences in university admissions, graduation rates within the University of California (UC) system increased by 4.4 percent. The researchers found that better matching of qualifications to university accounted for 18 percent of that increase, and investing more resources into remedial efforts caused anywhere from 23 percent to 64 percent of the increase.[42][43]

Evidence against mismatch

However, a 2009 study by William Bowen, Michael McPherson and Matthew M. Chingos found that "students were most likely to graduate by attending the most selective institution that would admit them" and that graduation rates actually decrease when students attend schools that are not challenging enough. In a separate article, Chingos criticized the NBER paper for ignoring graduation trends in the several years prior to California's affirmative action ban and found that graduation rates of minorities were already rising. He went on to say:[43]

| “ |

None of these alternative analyses of the effect of Prop 209 should be taken too seriously, because it is difficult to accurately estimate a pre-policy trend from only two data points. The bottom line is that there probably isn’t any way to persuasively estimate the effect of Prop 209 using these data. But this analysis shows how misleading it is in this case to only examine the 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 change, while ignoring the prior trend.[7] |

” |

| —Matthew M. Chingos | ||

Using a different method, Chingos also showed that as a general trend, even underqualified minorities are more likely to graduate from a more selective university, although results for each institution vary.[43]

State bans

As of February 2015, the use of racial preferences has been banned in eight states, colored in teal below. Colorado is the first and only state so far where a ballot initiative to ban racial preferences was rejected by voters. In addition, Texas had a ban in place from 1996 to 2003 via the lower court's ruling in Hopwood vs. Texas. This ruling was invalidated by the Supreme Court ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger. See the summary of major court cases for more information.

Arizona

A measure banning racial preferences was on the ballot in Arizona on November 2, 2010. Known as the Arizona Civil Rights Amendment, the measure was referred to the ballot by the state legislature as an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting the consideration of race in public employment, education and government contracting. It was approved by Arizona voters by 59.5 percent.[44]

California

The Regents of the University of California (UC) voted to end the use of racial preferences in admissions into the UC system in July 1995. This was followed in 1996 by a voter-approved ballot measure, Proposition 209, to eliminate racial preferences at all public institutions statewide. Due to legal challenges, the measure did not go into effect until 1998.[44]

As a substitute for racial preferences, in 1999 the University of California system adopted a policy to automatically admit high school students who graduate in the top 4 percent of their class. In 2012 the policy was expanded to the top 9 percent of high school graduates. The policy guarantees admission into one school, although not necessarily the student's school of choice.[44][45]

Colorado

A ballot measure to prohibit racial preferences in Colorado, the Colorado Discrimination and Preferential Treatment by Governments initiative, was narrowly defeated by voters in 2008. Had it been approved, the measure would have added a section to the state constitution barring consideration of race in public employment, education and contracting. Colorado was the first and only state where a ballot initiative to ban racial preferences was rejected by voters.[44][46]

Florida

In 1999, Florida Governor Jeb Bush (R) issued an Executive Order prohibiting the consideration of race in public employment, education and contracting. To replace racial preferences, the order created the admissions policy known as Talented Twenty, which guarantees high school students admission into a state college if they graduate in the top 20 percent of their class. Under the order, funding for need-based financial aid also increased. Florida is the only state to have banned racial preferences by Executive Order.[44]

Michigan

In 2006 Michigan voters approved the Michigan Civil Rights Amendment, a state constitutional amendment prohibiting racial preferences in public employment, education and contracting. The measure was overturned by the U.S. 6th Court of Appeals, but upheld in April 2014 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that voters have the right to ban affirmative action policies in the public sector.[44]

Nebraska

Nebraska's Civil Rights Initiative was passed by voters in 2008, adding a section to the state's constitution barring the consideration of race in public employment, education and contracting. The ballot initiative faced a legal challenge on the legitimacy of its signatures, but the Lancaster Circuit Court found that there was no evidence of fraud.[44][47]

New Hampshire

The New Hampshire state legislature passed House Bill 0623, a law prohibiting preferences in public employment, education and contracting "based on race, sex, national origin, religion, or sexual orientation." New Hampshire is the only state to have enacted such a measure via legislation.[44][37]

Oklahoma

Oklahoma became the most recent state to ban racial preferences when voters approved the Oklahoma Affirmative Action Ban Amendment in 2012. The measure, referred to the ballot by the state legislature, added a section to the state constitution barring preferential treatment "on the basis of race, color, sex, ethnicity or national origin" in public employment, education and contracting.[44]

Texas

The affirmative action policies of state universities in Texas was ended due to a court ruling in Hopwood vs. Texas in 1996. As a replacement, the Texas state legislature enacted HB 588, the 10 Percent Plan. The policy guaranteed admission into a Texas state university for all high school students who graduate in the top 10 percent of their class. In 2009 the number of students who could be admitted under the plan was limited to 75 percent of the incoming freshman class.

After the Hopwood decision was invalidated by Grutter vs. Bollinger in 2003, the University of Texas at Austin began using racial preferences once again, although Texas A&M did not. The 10 Percent Plan is still utilized by both universities.

Washington

Racial preferences were banned in Washington in 1998 by a ballot initiative similar to Proposition 209 in California. The Washington Affirmative Action Ban added a section to the state constitution prohibiting preferential treatment at public institutions according to race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin.[44]

Issues

Racial preferences

Although there are many different types of affirmative action, racial preferences towards underrepresented minorities is a well-known method. The terms "affirmative action" and "racial preferences" are often used interchangeably. The use of racial preferences, particularly in college admissions, has been challenged multiple times in the courts as a violation of the Equal Amendment Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Supporters of the policy say that without racial preferences, minority enrollment at selective institutions would fall far below current levels, as much as 60 percent by some estimates. Opponents of racial preferences say the policy actually harms minorities and leads to mismatch, as a preference can act as a 150- to 350-point adjustment to the student's SAT score.[35][38][39]

| Voting on Affirmative Action |

|---|

|

| Ballot Measures |

| By state |

| By year |

| Not on ballot |

Socioeconomic status vs. race

In response to issues brought against racial preferences, researchers and scholars have looked for alternatives to achieving diversity in university classrooms. Growing support, led in part by Richard Kahlenberg at The Century Foundation, has emerged for the consideration of socioeconomic status in admissions, rather than race. Supporters point to a study by Thomas Sowell at the Hoover Institution that found the main benefactors of affirmative action were already advantaged in that they belonged to the middle class. They argue that considering socioeconomic status would create true diversity on campus and would not be subject to the legal issues brought against racial preferences. Critics of the policy say that although minorities are more likely to belong to the lower class, the absolute number of low-income white students is higher than that of low-income black students. Thus, socioeconomic affirmative action would not be sufficient to maintain racial diversity.[4][48][49]

Student preparation

Because of the performance gap between black students and white students in college, some scholars question whether the use of racial preferences is the best way to improve the position of underrepresented minorities in society. According to 2012 article by Thomas J. Espenshade, at the time a sociology professor at Princeton University, the performance gap starts as early as kindergarten and continues through high school, where the average black student is four years behind the average white student. As a result, they typically enter college far less prepared. Some contend that the use of racial preferences would not be needed if this performance gap was closed earlier in life. They also advocate for more resources devoted to remediation and tutoring for struggling college students.[38]

Ballot measures lists

| |||||||||||||||||||

Recent news

This section links to a Google news search for the term "Affirmative + action"

See also

- State affirmative action information

- Affirmative action on the ballot

- Higher education in the United States

- Higher education by state

- Education policy in the United States

- Amendment XIV, United States Constitution

External links

- National Conference of State Legislatures, Affirmative Action Overview

- The Century Foundation

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

- Project on Fair Representation

- American Civil Liberties Union

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 National Conference of State Legislatures, "Affirmative Action | Overview," February 7, 2015

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Infoplease, "Affirmative Action History," accessed February 10, 2015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Infoplease, "Timeline of Affirmative Action Milestones," accessed February 10, 2015

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Miller Center of Public Affairs, "Affirmative Action: Race or Class?" accessed February 10, 2015

- ↑ The United States Department of Justice, "Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," accessed February 24, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, "Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," accessed February 24, 2015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Legal Information Institute, "Regents of the Uni v. of Cal. v. Bakke," accessed May 28, 2015

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Supreme Court of the United States, "Students for Fair Admission, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard CollegeStudents for Fair Admission, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College," accessed June 29, 2023

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 AP News, "Divided Supreme Court outlaws affirmative action in college admissions, says race can’t be used," accessed June 29, 2023

- ↑ Infoplease, "Regents of the University of California v. Bakke," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Oyez, "Regents of the University of California v. Bakke," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ The Center for Individual Rights, "Hopwood v. Texas," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Oyez, "Gratz v. Bollinger," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ FindLaw, "GRUTTER v. BOLLINGER et al.," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Justia, "Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Oyez, "Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Oyez, "Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Oyez, "Ricci v. DeStefano," accessed February 24, 2015

- ↑ Oyez, "Fisher v. University of Texas," accessed February 11, 2015

- ↑ Justia, "Grutter v. Bollinger," accessed June 29, 2023

- ↑ Students for Fair Admission, "About," accessed June 29, 2023

- ↑ SCOTUSblog, "Supreme Court strikes down affirmative action programs in college admissions," accessed June 29, 2023

- ↑ The New York Times, "Answers on Affirmative Action Depend on How You Pose the Question," April 22, 2014

- ↑ CBS News, "Poll: Slim majority backs same-sex marriage," June 6, 2013

- ↑ Gallup, "In U.S., Most Reject Considering Race in College Admissions," July 24, 2013

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Pew Research Center, "Optimism about Black Progress Declines," November 13, 2007

- ↑ NBC News, "NBC News/WSJ poll: Affirmative action support at historic low," June 11, 2013

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 BalancedPolitics.org, "Should affirmative action policies, which give preferential treatment based on minority status, be eliminated?" accessed February 16, 2015

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 ProCon.org, "Does the US Need Affirmative Action?" accessed February 24, 2015

- ↑ Salon, "A "poison" divides us," March 27, 2000

- ↑ Center for Individual Rights, "Mission," accessed February 24, 2015

- ↑ Harvard Kennedy School, "The Effects of Affirmative Action Bans on College Enrollment, Educational Attainment, and the Demographic Composition of Universities," accessed February 18, 2015

- ↑ The Journal of Human Resources, "Do Affirmative Action Bans Lower Minority College Enrollment and Attainment?" accessed February 18, 2015

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Sander, R. & Taylor S. (2012). Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It's Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won't Admit It. Basic Books.

- ↑ The New York Times, "How Minorities Have Fared in States With Affirmative Action Bans," April 22, 2014

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 The Century Foundation, "What Can We Learn from States That Ban Affirmative Action?" June 26, 2014

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 The New York Times, "Moving Beyond Affirmative Action," October 4, 2012

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 The New York Times, "Does Affirmative Action Do What It Should?" March 16, 2013

- ↑ The Wall Street Journal, "Amid Affirmative Action Ruling, Some Data on Race and College Enrollment," April 22, 2014

- ↑ The Wall Street Journal, "The Unraveling of Affirmative Action," October 13, 2012

- ↑ The National Bureau of Economic Research, "Affirmative Action and University Fit: Evidence from Proposition 209," accessed February 17, 2015

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 The Brookings Institution, "Are Minority Students Harmed by Affirmative Action?" March 7, 2013

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 44.6 44.7 44.8 44.9 National Conference of State Legislatures, "State Action," accessed February 19, 2015

- ↑ University of California Admissions, "Local path (ELC)," accessed February 19, 2015

- ↑ Colorado State Legislative Council, "Ballot History," accessed February 19, 2015

- ↑ Omaha World Herald, "Ban's opponents lose in court," January 23, 2009

- ↑ Stanford Alumni, "The Case Against Affirmative Action," accessed February 19, 2015

- ↑ Yale Daily News, "UP CLOSE: What’s next for affirmative action?" September 22, 2014

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||