The 509th Composite Group was the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Prior to being stationed on Tinian Island, the 509th underwent extensive training with the modified B-29 Superfortress at Wendover Army Air Field in Wendover, Utah. On August 6 and 9, airmen of the 509th flew from Tinian Island to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, carrying the Little Boy and Fat Man atomic bombs.

Creation of the 509th

While scientists of the Manhattan Project focused on the functionality of the atomic bomb, Project Alberta, headed by Captain William “Deak” Parsons, focused on the plans for delivering the bomb. There were two components of this challenge: developing planes to carry the bomb, and training airmen to fly them. Project Silverplate, which focused on designing the planes to carry the bomb, was started as early as October of 1943. The 509th Composite Group, the crew to man these planes, was created in 1944.

The first step was identifying the man who would command the unit. Captain Parsons, Norman Ramsey, and John Lansdale of Project Alberta met with Colonel R. C. Wilson from the Air Forces. They selected Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, a pilot with exceptional record in bombing missions in Germany and experience with B-29’s.

On September 1, 1944, Tibbets was appointed to be the commander of an organization that “might shorten the war.” He was charged with training crews to fly modified B-29s that would eventually carry a 9,000-pound bomb. The bomb would need to be accurately dropped from a safe distance of eight miles away, and the pilot needed to perfect dramatic turns and dives to avoid the bomb’s blast. In addition, throughout training, the men would not be allowed to know the purpose of their unit. For a final layer of secrecy, this unit was to be a “composite group,” meaning all necessary support groups would be part of the unit, including air service crews.

Other groups in the military became part of the 509th, particularly the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, which was transferred from Nebraska to Wendover in September 1944. (The transfer was requested before Col. Tibbets took command.) The 393rd was originally part of the 504th Bombardment Group, which was subsequently deployed to the Pacific and conducted bombing operations from Tinian. Other forces which joined the 509th Composite Group included the 390th Air Service Group, the 603rd Air Engineering Squadron, the 1027th Air Materiel Squadron, the 320th Troop Carrier Squadron, the 1395th Military Police Company, and the First Ordnance Squadron. In total, the 509th came to include 225 officers and 1542 men.

“These people had to be the best,” Tibbets remembered in an interview in 1989. “I wanted the best I could get, and we did have a rather tough selective process.”

Tibbets’ men were some of the best pilots, navigators, and flight engineers in the entire U.S. military, as Tibbets was able to commandeer men from missions all over the globe. The most important qualities to Tibbets were loyalty and secrecy. He tolerated raucous behavior among his men, so long as he knew they would not tell anyone about what they were doing. Even though they knew very little about what they were training for, members of the 509th were required to remain secretive.

“We were told in the original speech by Colonel Tibbets that ‘You don’t discuss with anyone where you are, who you are, what you’re doing. With your wife, your mother, your sister, your girlfriend or anything,’ 509th Composite Group member Jack Widowsky recalled in an interview with the Atomic Heritage Foundation in 2016. “Every once in a while, one of our fellows ended up in Alaska because they opened their mouth too much. They shipped them out immediately.”

Initial Training at Wendover

On December 17, 1944, the 509th Composite Group was officially activated at Wendover, Utah. At Wendover, the men practiced flying the modified B-29 Superfortress. They practiced bomb release and target aiming by dropping “pumpkin bombs,” or specially designed bombs that mimicked the atomic bombs in their unique shape and heavy weight. These practice bombings helped engineers make final modifications to the planes in terms of weight distribution. At this time, special pits were also designed to load the large, heavy bombs into the planes.

In January 1945, part of the 393rd group was sent to Batista Field in Cuba for three months, where they practiced high-altitude coastal and ocean flying, as well as long-range navigation. High-altitude bombing was a new tactic in 1944, and Tibbets relentlessly drove his flight crews to increase the accuracy of their bomb drops. The crew also practiced steep diving maneuvers; this was the only way, Tibbets believed, a B-29 would be able to escape an atomic bomb’s blast.

Stationed at Tinian Island

In late May, the 509th was moved to Tinian Island, where they operated combat missions starting June 30, 1945. They dropped bombs on Japanese-controlled islands throughout July to practice radar and visual bombing procedures, in addition to dropping pumpkin bombs in Japan, and practicing missions with inert Little Boy and Fat Man prototypes.

At Tinian, Parsons led the scientists, engineers, and officers of Project Alberta, while Tibbets oversaw the operations of the 509th. In terms of authority, General Thomas Farrell, Admiral William Purnell, and Parsons informally formed the “Tinian Joint Chiefs.” Tibbets would be included in the decision-making process as needed. Due to the sensitive nature of their mission, these men reported directly to General Leslie Groves.

Other security measures included keeping the modified B-29s in an isolated corner of the base. Access was heavily restricted. Guards themselves were often unaware of the importance of what they were protecting.

Tibbets recalled one incident between Commanding General of 313th Bombardment Wing James Davies and a guard. Tibbets was not there for the incident, but Davies later spoke to him about it.

Davies told Tibbets that he had gone to take a look at the special B-29s when he was told by the guard that he did not have the proper pass. Davies informed the guard that he was the commanding officer.

To this, the guard replied, “I recognize you,” and still refused to let Davies enter.

According to Davies, this made him “unhappy.” He threw his identification at the guard and yelled, “I am going to look at the plane!”

The guard lowered his rifle, cocked it, and said, “One more step, General, and you are dead.”

Davies later asked Tibbets, “Would he have pulled the trigger?”

Tibbets responded, “There is no doubt in my mind.”

The island buzzed with rumors as a result of the secrecy. It also led to ridicule, perhaps stemming from jealousy, as rumors swirled that the 509th were “going to win the war.” One example, is the poem “Nobody Knows.” Part of it has been reproduced below, as quoted in Al Christman’s book Target Hiroshima:

“Into the air the secret rose,

Where they’re going, nobody knows…

When other groups are ready to go,

We have a program for the whole damn show…

But with this new bunch we haven’t a chance.

We should have been home a month or more,

For the 509th is winning the war.”

The security measures ultimately were successful. One Japanese Imperial Staff report, in reference to the 509th, stated: “One other unit is available but its identity has not been ascertained yet.” Until the bombing of Hiroshima, Japan had no idea what it was facing.

From Trinity to Hiroshima

On July 16, 1945 the first nuclear device was successfully tested at Trinity Site in the New Mexico desert. Riding in the B-29 that was observing the test from the air, Parsons knew this was the signal for final preparations of the 509th and Alberta. From July 23 to July 31, components of Little Boy and Fat Man began traveling to Tinian. The “gun-type” mechanism for Little Boy and half of the supply of uranium arrived on the ill-fated USS Indianapolis. The rest of the uranium was flown over. On July 31, Parsons declared the testing and training complete for the delivery of the first bomb. On August 1, Little Boy was ready for loading and delivery, and on August 3, Major General Curtis LeMay brought orders for Special Bombing Mission Thirteen. The mission was to be carried out as soon as the weather cleared in Japan.

On August 4, four loaded B-29s crashed on takeoff, which caused their ammunition and bombs to explode. The incident worried Parsons and few others, who knew the vast destructive potential of an atomic bomb. It reiterated the importance of assembling the bombs in flight to avoid the risk of the device detonating if a plane crashed on takeoff.

Later that day, men of the 509th Composite Group assembled for a briefing. Finally, Tibbets told the men about their mission to bomb Japan and the immensely destructive nature of the bomb. Tibbets did not, however, reveal it was a nuclear weapon. At this briefing were the six crews of the 509th that would participate in dropping Little Boy and top officials from Washington. A seventh crew was sent to Iwo Jima as back-up and was debriefed separately.

“During your training period you were called upon to do many strange things,” Tibbets said. “There was a reason for all of that, because this bomb that you are going to use is not an ordinary bomb. It is not a thousand pounder, it is not a ten ton blockbuster, this bomb has the strength of twenty thousand tons of TNT.”

The 509th were further informed that the mission would occur as soon as the weather cleared, what their targets were, and that the Japanese would not be expecting them. Three crews were to fly ahead to assess the weather, and relay the information to the bomb carrier. The other two crews were to accompany the bomb carrier as observation units. Finally, the men were told that until the mission occurred, they could not discuss the mission, even among themselves.

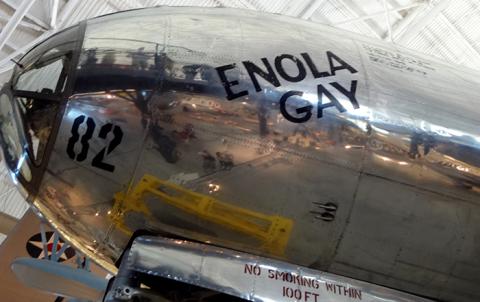

On August 5, the mission was confirmed as the weather cleared. Tibbets took over as the pilot of the strike plane, which he named “Enola Gay” after his mother. Parsons was the weaponeer. “Little Boy” was loaded onto the plane. At 2:45am Tinian time, the Enola Gay, accompanied by two observation planes, took off towards Hiroshima, and at approximately 8:15am Hiroshima time dropped Little Boy. (More on the bombings here.) The crews arrived back in Tinian at 2:58pm, after about 12 hours in the air.

Nagasaki

On August 9, 1945, members of 509th were convened to drop the bomb. Four planes and four crews from the Hiroshima mission flew again, but in different roles.

Notable figures who participated in both the Nagasaki and Hiroshima missions include Lawrence H. Johnston, who was the only person to witness Trinity and both bombings, and Jacob Beser, who was the only person to fly aboard the strike plane for both missions.

The planes took off at 3:49am Tinian, and they ran into a delay at a rendezvous point while waiting for Big Stink to arrive. After waiting 45 minutes, Bockscar and The Great Artiste continued on. When the initial target, Kokura, was revealed to be obscured by clouds, they proceeded to Nagasaki. Although under strict orders to drop the bomb visually, after fifty minutes of waiting for clear conditions, depleting the limited fuel tank, the ultimate call was made to drop the bomb by radar. At the last minute, a break in the clouds emerged and enabled the bombardier to release visually.

Due to the fuel shortage, Bockscar made an emergency landing at Okinawa at 2:00pm Tinian time. They landed with seven gallons of fuel left, which was less than a minute of flight for the B-29 Superfortress. After three hours at the Yontan Air Base, it arrived at Tinian at 11:06pm. The total mission time was 19 hours.

The two missions, while both successful in delivering atomic bombs, were almost opposites in their execution. While the Hiroshima mission ran into few obstacles, the Nagasaki mission was subject to the threat of bad weather, lack of reserve fuel, and last-minute decisions to change the bombing location. There is also some controversy over factors of ambiguous command relationship that may or may not have contributed to the difficulty of this mission.

After the War

The 509th Composite Group had officially completed its mission that it had been specifically created and trained for: to deliver the atomic bombs. On Oct 17, 1945, the 509th departed Tinian aboard the transport ship SS Deuel. It arrived at Oakland on November 5, 1945 and proceeded to Roswell, New Mexico, where it was reassigned to a new commander and later became part of the Strategic Air Command.

In 1946, the 509th would be assigned to Operation Crossroads, a series of nuclear weapons tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

- For a more detailed timeline of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, click here.

- For more oral histories from the 509th Composite group, click here.

- From a dramatic retelling of the Hiroshima Mission: click here.