-

A Two-Level Facility Layout Design Method with the Consideration of High-Risk Facilities in Chemical Industries

-

Effect of UV Exposure Time on the Properties of Films Prepared from Biotechnologically Derived Chicken Gelatin

-

3D Printed Ni–Cu Sodalite Catalysts for Sustainable γ-Valerolactone Production from Levulinic Acid—Effect of the Copper Content and the Method of Preparation

Journal Description

Processes

Processes

is an international, peer-reviewed, open access journal on processes/systems in chemistry, biology, material, energy, environment, food, pharmaceutical, manufacturing, automation control, catalysis, separation, particle and allied engineering fields published monthly online by MDPI. The Systems and Control Division of the Canadian Society for Chemical Engineering (CSChE S&C Division) and the Brazilian Association of Chemical Engineering (ABEQ) are affiliated with Processes and their members receive discounts on the article processing charges. Please visit Society Collaborations for more details.

- Open Access— free for readers, with article processing charges (APC) paid by authors or their institutions.

- High Visibility: indexed within Scopus, SCIE (Web of Science), Ei Compendex, Inspec, AGRIS, and other databases.

- Journal Rank: JCR - Q2 (Engineering, Chemical) / CiteScore - Q2 (Chemical Engineering (miscellaneous))

- Rapid Publication: manuscripts are peer-reviewed and a first decision is provided to authors approximately 14.9 days after submission; acceptance to publication is undertaken in 2.7 days (median values for papers published in this journal in the second half of 2024).

- Recognition of Reviewers: reviewers who provide timely, thorough peer-review reports receive vouchers entitling them to a discount on the APC of their next publication in any MDPI journal, in appreciation of the work done.

Impact Factor:

2.8 (2023);

5-Year Impact Factor:

3.0 (2023)

Latest Articles

A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Model for Lost Circulation Monitoring Using Wavelet Transform and TimeGAN

Processes 2025, 13(3), 813; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030813 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

Lost circulation is a major challenge in the drilling process, which seriously restricts the safety and efficiency of drilling. The traditional monitoring model is hindered by the presence of noise and the complexity of temporal fluctuations in lost circulation data, resulting in a

[...] Read more.

Lost circulation is a major challenge in the drilling process, which seriously restricts the safety and efficiency of drilling. The traditional monitoring model is hindered by the presence of noise and the complexity of temporal fluctuations in lost circulation data, resulting in a suboptimal performance with regard to accuracy and generalization ability, and it is not easy to adapt to the needs of different working conditions. To address these limitations, this study proposes a multi-scale feature fusion model based on wavelet transform and TimeGAN. The wavelet transform enhances the features of time series data, while TimeGAN (Time Series Generative Adversarial Network) excels in generating realistic time series and augmenting scarce or missing data. This model uses convolutional network feature extraction and a multi-scale feature fusion module to integrate features and capture time sequence information. The experimental findings demonstrate that the multi-scale feature fusion model proposed in this study enhances the accuracy by 8.8%, reduces the missing alarm rate and false alarm rate by 12.4% and 6.2%, respectively, and attains a test set accuracy of 93.8% and precision of 95.1% in the lost circulation identification task in comparison to the unoptimized model. The method outlined in this study provides reliable technical support for the monitoring of lost circulation risk, thereby contributing to the enhancement of safety and efficiency in the drilling process.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Section Energy Systems)

Open AccessArticle

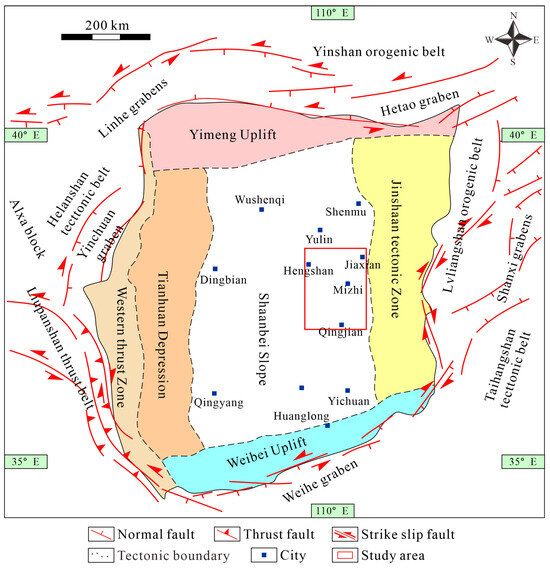

Gas–Water Distribution and Controlling Factors in a Tight Sandstone Gas Reservoir: A Case Study of Southern Yulin, Ordos Basin, China

by

Tiezhu Tang, Hongyan Li, Ling Fu, Sisi Chen and Jiahao Wang

Processes 2025, 13(3), 812; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030812 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

The intricate gas–water distribution patterns in tight sandstone gas reservoirs significantly impede effective exploration and development, particularly challenging sweet spot prediction. In the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation of the Ordos Basin, the complex and variable gas–water distribution characteristics remain poorly understood regarding their

[...] Read more.

The intricate gas–water distribution patterns in tight sandstone gas reservoirs significantly impede effective exploration and development, particularly challenging sweet spot prediction. In the Upper Paleozoic Shanxi Formation of the Ordos Basin, the complex and variable gas–water distribution characteristics remain poorly understood regarding their spatial patterns and controlling mechanisms. This study employs an integrated analytical approach combining casting thin sections, conventional porosity–permeability measurements, and mercury intrusion porosimetry to systematically investigate the petrological characteristics, pore structure, and physical properties of the Shan 2 member reservoirs in southern Yulin. Through the comprehensive analysis of production data coupled with structural and sand body distribution patterns, we identify three predominant formation water types: edge/bottom water, isolated lens-shaped water bodies, and residual water in tight sandstone gas layers. Our findings reveal that three primary factors govern water distribution in the Shan 2 member reservoirs: sand body architecture controlling fluid migration pathways; reservoir quality determining fluid storage capacity; and structural configuration influencing fluid accumulation patterns. This multi-scale characterization provides critical insights for optimizing development strategies in similar tight sandstone reservoirs.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Section Energy Systems)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>The division of tectonic units and the location of the research area in the Ordos Basin.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Classification of reservoir rocks in study area (Q: quartz; F: feldspar; R: rock fragment). (<b>a</b>) Shan 1; (<b>b</b>) Shan 2.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Thin sections of the sandstone reservoirs in the study area: (<b>a</b>) Intergranular pores and feldspar dissolution pores, Q11, 2734 m. (<b>b</b>) Kaolinite intercrystalline pores, Q38, 2784 m. (<b>c</b>) Quartz overgrowth, Y55, 2579 m. (<b>d</b>) Feldspar dissolution pores and kaolinite intercrystalline pores, Y108, 2404 m. (<b>e</b>) Deformed mica, M60, 2104 m. (<b>f</b>) Kaolinite intercrystalline pores, M68, 2537 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Edge/bottom water distribution characteristics.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Isolated lens-shaped water bodies’ distribution characteristics.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Distribution characteristics of residual water in tight sandstone gas layers.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Distribution pattern diagram of formation water in Shanxi Formation.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Composite plan view of water bodies, sand bodies, and top surface structures in Shan 23 member. The distribution of sand body thickness, with the blue line representing the structure, showing an overall structural characteristic of being high in the east and low in the west. The formation water is mostly concentrated in the lower part of the formation.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Composite plan view of water bodies and sand bodies in Shan 23 member. Sand bodies zone exhibit bending and pinch-out features are identified as critical areas for the accumulation of formation water.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Intersection plot of daily gas production and porosity–permeability in Shan 23 member.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Intersection plot of daily water production and porosity–permeability in Shan 23 member.</p> Full article ">

<p>The division of tectonic units and the location of the research area in the Ordos Basin.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Classification of reservoir rocks in study area (Q: quartz; F: feldspar; R: rock fragment). (<b>a</b>) Shan 1; (<b>b</b>) Shan 2.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Thin sections of the sandstone reservoirs in the study area: (<b>a</b>) Intergranular pores and feldspar dissolution pores, Q11, 2734 m. (<b>b</b>) Kaolinite intercrystalline pores, Q38, 2784 m. (<b>c</b>) Quartz overgrowth, Y55, 2579 m. (<b>d</b>) Feldspar dissolution pores and kaolinite intercrystalline pores, Y108, 2404 m. (<b>e</b>) Deformed mica, M60, 2104 m. (<b>f</b>) Kaolinite intercrystalline pores, M68, 2537 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Edge/bottom water distribution characteristics.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Isolated lens-shaped water bodies’ distribution characteristics.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Distribution characteristics of residual water in tight sandstone gas layers.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Distribution pattern diagram of formation water in Shanxi Formation.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Composite plan view of water bodies, sand bodies, and top surface structures in Shan 23 member. The distribution of sand body thickness, with the blue line representing the structure, showing an overall structural characteristic of being high in the east and low in the west. The formation water is mostly concentrated in the lower part of the formation.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Composite plan view of water bodies and sand bodies in Shan 23 member. Sand bodies zone exhibit bending and pinch-out features are identified as critical areas for the accumulation of formation water.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Intersection plot of daily gas production and porosity–permeability in Shan 23 member.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Intersection plot of daily water production and porosity–permeability in Shan 23 member.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Deep Neural Network Model Based on Process Mechanism Applied to Predictive Control of Distillation Processes

by

Zirun Wang, Hao Wang and Zengzhi Du

Processes 2025, 13(3), 811; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030811 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

In modern process industries, precise process modeling plays a vital role in intelligent manufacturing. Nevertheless, both mechanistic and data-driven modeling methods have their own limitations. To address the shortcomings of these two modeling methods, we propose a neural network model based on process

[...] Read more.

In modern process industries, precise process modeling plays a vital role in intelligent manufacturing. Nevertheless, both mechanistic and data-driven modeling methods have their own limitations. To address the shortcomings of these two modeling methods, we propose a neural network model based on process mechanism knowledge, aiming to enhance the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the model. The basic structure of this neural network consists of gated recurrent units and an attention mechanism. According to the different properties of the variables to be predicted, we propose an improved neural network with a distributed structure and residual connections, which enhances the interpretability of the neural network model. We use the proposed model to conduct dynamic modeling of a benzene–toluene distillation column. The mean squared error of the trained model is 0.0015, and the error is reduced by 77.2% compared with the pure RNN-based model. To verify the prediction ability of the proposed predictive model beyond the known dataset, we apply it to the predictive control of the distillation column. In two tests, it achieves results far superior to those of the PID control.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Advances in Process Systems Engineering: Selected Papers from China PSE Annual Meeting)

Open AccessReview

The Development of a River Quality Prediction Model That Is Based on the Water Quality Index via Machine Learning: A Review

by

Hassan Shaheed, Mohd Hafiz Zawawi and Gasim Hayder

Processes 2025, 13(3), 810; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030810 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

This review, “The Development of a River Quality Prediction Model That Is Based on the Water Quality Index using Machine Learning: A Review”, discusses and evaluates research articles and attempts to incorporate ML algorithms into the water quality index (WQI) to improve the

[...] Read more.

This review, “The Development of a River Quality Prediction Model That Is Based on the Water Quality Index using Machine Learning: A Review”, discusses and evaluates research articles and attempts to incorporate ML algorithms into the water quality index (WQI) to improve the prediction of river water quality. This original study confirms how new methodologies like LSTM, CNNs, and random forest perform better than previous methods, as they offer real-time predictions, operational cost saving, and opportunities for handling big data. This review finds that, in addition to good case studies and real-life applications, there is a need to expand in the following areas: impacts of climate change, ways of enhancing data representation, and concerns to do with ethics as well as data privacy. Furthermore, this review outlines issues, such as data scarcity, model explainability, and computational overhead in real-world ML applications, as well as strategies to preemptively address these issues in order to improve the versatility of data-driven models in various domains. Moving to the analysis of the review specifically to discuss the propositions, the identified key points focus on the use of complex approaches and interdisciplinarity and the involvement of stakeholders. Due to the added specificity and depth in a number of comparisons and specific technical and policy discussions, this sweeping review offers a broad view of how to proceed in enhancing the usefulness of the predictive technologies that will be central to environmental forecasting.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Section Advanced Digital and Other Processes)

Open AccessFeature PaperArticle

Mechanical Recycling of Crosslinked High-Density Polyethylene (xHDPE)

by

Hibal Ahmad and Denis Rodrigue

Processes 2025, 13(3), 809; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030809 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

This study introduces a mechanical recycling technique for crosslinked high-density polyethylene (xHDPE) using cryogenic pulverization and compression molding. This method is shown to effectively transform xHDPE into valuable fillers for recycled HDPE (rHDPE(B)) sourced from recycled bottles using different concentrations (15–60%) and particle

[...] Read more.

This study introduces a mechanical recycling technique for crosslinked high-density polyethylene (xHDPE) using cryogenic pulverization and compression molding. This method is shown to effectively transform xHDPE into valuable fillers for recycled HDPE (rHDPE(B)) sourced from recycled bottles using different concentrations (15–60%) and particle sizes (0–250 µm, 250–500 µm, and 500–1000 µm). In particular, the recycling method significantly reduced the gel content from 60.5% to 41.8% for the 0–250 µm particles, indicating partial decrosslinking. Morphological analysis revealed good interfacial adhesion between rHDPE(B) and recycled xHDPE (r-xHDPE), improving the overall performance and resulting in a balanced combination of properties from both materials. The r-xHDPE samples exhibited improved thermal stability. While particle size had minimal effect on material properties, increasing its concentration significantly improved impact strength (612%) with a slight (3%) reduction in density at 60% 500–1000 µm particles. This research underscores the possibility of recycling crosslinked polymers and highlights the need for further studies to optimize the material properties and expand the methodology to a wider range of polymers.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Novel Recovery Technologies from Wastewater and Waste)

Open AccessArticle

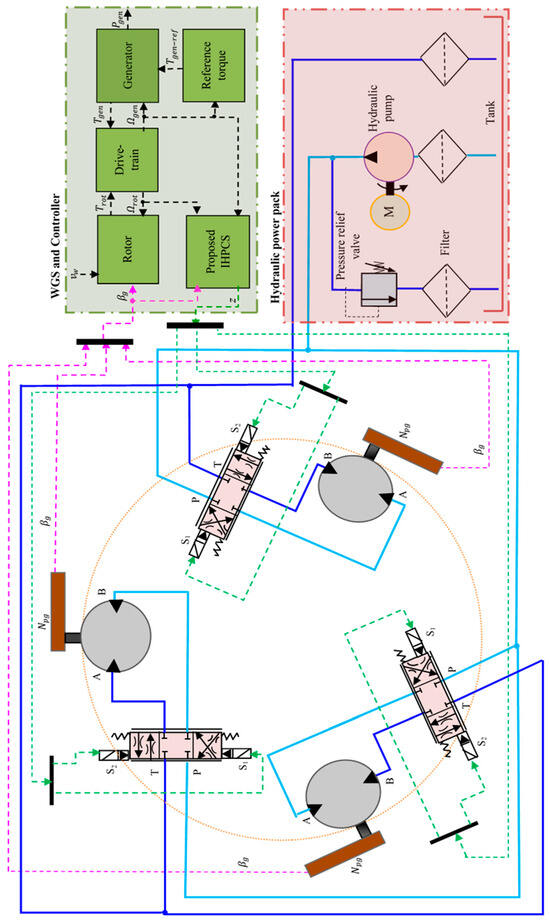

Elman Neural Network with Customized Particle Swarm Optimization for Hydraulic Pitch Control Strategy of Offshore Wind Turbine

by

Valayapathy Lakshmi Narayanan, Jyotindra Narayan, Dheeraj Kumar Dhaked and Achraf Jabeur Telmoudi

Processes 2025, 13(3), 808; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030808 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

Offshore wind turbines have garnered significant attention recently due to their substantial wind energy harvesting capabilities. Pitch control plays a crucial role in maintaining the rated generator speed, particularly in offshore environments characterized by highly turbulent winds, which pose a huge challenge. Moreover,

[...] Read more.

Offshore wind turbines have garnered significant attention recently due to their substantial wind energy harvesting capabilities. Pitch control plays a crucial role in maintaining the rated generator speed, particularly in offshore environments characterized by highly turbulent winds, which pose a huge challenge. Moreover, hydraulic pitch systems are favored in large-scale offshore wind turbines due to their superior power-to-weight ratio compared to electrical systems. In this study, a proportional valve-controlled hydraulic pitch system is developed along with an intelligent pitch control strategy aimed at developing rated power in offshore wind turbines. The proposed strategy utilizes a cascade configuration of an improved recurrent Elman neural network, with its parameters optimized using a customized particle swarm optimization algorithm. To assess its effectiveness, the proposed strategy is compared with two other intelligent pitch control strategies, the cascade improved Elman neural network and cascade Elman neural network, and tested in a benchmark wind turbine simulator. Results demonstrate effective power generation, with the proposed strategy yielding a 78.14% and 87.10% enhancement in the mean standard deviation of generator power error compared to the cascade improved Elman neural network and cascade Elman neural network, respectively. These findings underscore the efficacy of the proposed approach in generating rated power.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Model Based, Data Driven Identification and Control for Developing Intelligent and Smart Processes and Systems)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Proposed pitch system.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Drivetrain dynamics.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Proposed IHPCS framework.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Structure of IRENN.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Cascade IENN framework.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Cascade ENN framework.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Proposed pitch control strategy implemented in FAST.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Validation via FAST: (<b>a</b>) STD of pitch angle error; (<b>b</b>) STD of generator speed error; (<b>c</b>) STD of generator power error.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Validation via FAST: (<b>a</b>) wind speed; (<b>b</b>) pitch angle generated; (<b>c</b>) pitch angle error; (<b>d</b>) generator speed; (<b>e</b>) generator power.</p> Full article ">

<p>Proposed pitch system.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Drivetrain dynamics.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Proposed IHPCS framework.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Structure of IRENN.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Cascade IENN framework.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Cascade ENN framework.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Proposed pitch control strategy implemented in FAST.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Validation via FAST: (<b>a</b>) STD of pitch angle error; (<b>b</b>) STD of generator speed error; (<b>c</b>) STD of generator power error.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Validation via FAST: (<b>a</b>) wind speed; (<b>b</b>) pitch angle generated; (<b>c</b>) pitch angle error; (<b>d</b>) generator speed; (<b>e</b>) generator power.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessFeature PaperReview

Strategies for Strontium Recovery/Elimination from Various Sources

by

Jose Ignacio Robla, Lorena Alcaraz and Francisco Jose Alguacil

Processes 2025, 13(3), 807; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030807 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

Not having the same grade of popularity as other metals like rare earth elements, gold, copper, etc., strontium is a chemical element with wide uses in daily life, which is why it appears in the EU 2023 list of Critical Raw Materials. Among

[...] Read more.

Not having the same grade of popularity as other metals like rare earth elements, gold, copper, etc., strontium is a chemical element with wide uses in daily life, which is why it appears in the EU 2023 list of Critical Raw Materials. Among the sources (with celestine serving as the raw material) used to recover the element, the recycling of some Sr-bearing secondary wastes is under consideration, and it is also worth mentioning the interest in the removal of strontium from radioactive effluents. To reach these goals, several technological alternatives are being proposed, with the most widely used being the adsorption of strontium or one of its isotopes on solid materials. The present work reviews the most recent advances (for 2024) in the utilization of diverse technologies, including leaching, adsorption, liquid–liquid extraction, etc., in the recovery/elimination of Sr(II) and common 90Sr and 85Sr radionuclides present in different solid or liquid wastes. While adsorption and membrane technologies are useful for treating Sr-diluted solutions (in the mg/L order), liquid–liquid extraction is more suitable for the treatment of Sr-concentrated solutions (in the g/L order).

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Recycling and Value-Added Utilization of Secondary Resources)

Open AccessArticle

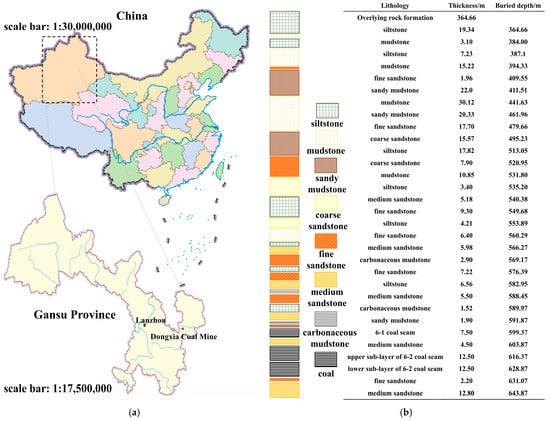

Dynamic Evolution of Fractures in Overlying Rocks Caused by Coal Mining Based on Discrete Element Method

by

Junyu Xu, Jienan Pan, Meng Li, Haoran Wang and Jiangfeng Chen

Processes 2025, 13(3), 806; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030806 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

Mining-induced fractures and overlying rock movement change rock layer porosity and permeability, raising water intrusion risks in the working face. This study explores fracture development in working face 31123-1 at Dongxia Coal Mine using UDEC 7.0 software and theoretical analysis. The overlying rock

[...] Read more.

Mining-induced fractures and overlying rock movement change rock layer porosity and permeability, raising water intrusion risks in the working face. This study explores fracture development in working face 31123-1 at Dongxia Coal Mine using UDEC 7.0 software and theoretical analysis. The overlying rock movement is a dynamic, spatially evolving process. As the working face advances, the water-conducting fracture zone height (WFZH) increases stepwise, and their relationship follows an S-shaped curve. Numerical simulations give a WFZH of about 112 m and a fracture–mining ratio of 14.93. Empirical formulas suggest a WFZH of 85.43 to 106.3 m and a ratio of 11.39 to 14.17. Key stratum theory calculations show that mining-induced fractures reach the 16th coarse-sandstone layer, with a WFZH of 97 to 113 m and a ratio of 12.93 to 15.07. Simulations confirm trapezoidal fractures with bottom angles of 48° and 50°, consistent with rock mechanics theories. A fractal permeability model for the mined overburden, based on the K-C equation, shows that fracture permeability positively correlates with the fractal dimension. These results verify the reliability of simulations and analyses, guiding mining and water control in this and similar working faces.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Exploration, Exploitation and Utilization of Coal and Gas Resources, 2nd Edition)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Location and lithology of working face 31123-1 in Dongxia coal mine: (<b>a</b>) location and (<b>b</b>) lithology.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>UDEC 2-D profile numerical model of working face 31123-1.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Variations in the lateral pressure coefficient with burial depth [<a href="#B14-processes-13-00806" class="html-bibr">14</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Model boundary conditions.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Fixed-ended beam model.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Initial equilibrium in numerical simulation.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Schematic diagram showing the stress components.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Dynamic evolution of fracture field in excavation steps from 0 to 300 m: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 30 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 40 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 50 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 60 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 80 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 100 m; (<b>i</b>) excavation steps = 110 m; (<b>j</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>k</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>l</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>m</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>n</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 8 Cont.

<p>Dynamic evolution of fracture field in excavation steps from 0 to 300 m: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 30 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 40 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 50 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 60 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 80 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 100 m; (<b>i</b>) excavation steps = 110 m; (<b>j</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>k</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>l</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>m</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>n</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Workface mining-induced fracture binary maps and fractal dimension maps, where D is the fractal dimension: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 120 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 9 Cont.

<p>Workface mining-induced fracture binary maps and fractal dimension maps, where D is the fractal dimension: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 120 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Fractal dimension distribution characteristics of overburden.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Correlation between the excavation steps and the WFZH.</p> Full article ">

<p>Location and lithology of working face 31123-1 in Dongxia coal mine: (<b>a</b>) location and (<b>b</b>) lithology.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>UDEC 2-D profile numerical model of working face 31123-1.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Variations in the lateral pressure coefficient with burial depth [<a href="#B14-processes-13-00806" class="html-bibr">14</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Model boundary conditions.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Fixed-ended beam model.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Initial equilibrium in numerical simulation.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Schematic diagram showing the stress components.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Dynamic evolution of fracture field in excavation steps from 0 to 300 m: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 30 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 40 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 50 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 60 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 80 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 100 m; (<b>i</b>) excavation steps = 110 m; (<b>j</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>k</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>l</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>m</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>n</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 8 Cont.

<p>Dynamic evolution of fracture field in excavation steps from 0 to 300 m: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 30 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 40 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 50 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 60 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 80 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 100 m; (<b>i</b>) excavation steps = 110 m; (<b>j</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>k</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>l</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>m</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>n</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Workface mining-induced fracture binary maps and fractal dimension maps, where D is the fractal dimension: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 120 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 9 Cont.

<p>Workface mining-induced fracture binary maps and fractal dimension maps, where D is the fractal dimension: (<b>a</b>) excavation steps = 70 m; (<b>b</b>) excavation steps = 90 m; (<b>c</b>) excavation steps = 120 m; (<b>d</b>) excavation steps = 160 m; (<b>e</b>) excavation steps = 200 m; (<b>f</b>) excavation steps = 240 m; (<b>g</b>) excavation steps = 280 m; and (<b>h</b>) excavation steps = 300 m.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Fractal dimension distribution characteristics of overburden.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Correlation between the excavation steps and the WFZH.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

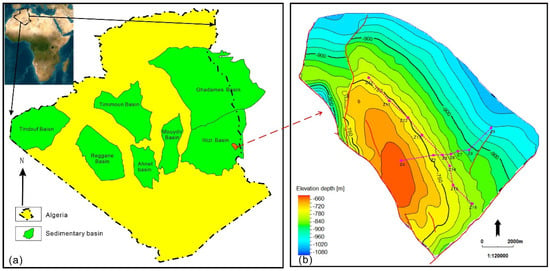

Reservoir Architecture of Turbidite Lobes and Remaining Oil Distribution: A Study on the B Formation for Z Oilfield of the Illizi Basin, Algeria

by

Changhai Li, Weiqiang Li, Huimin Ye, Qiang Zhu, Xuejun Shan, Shengli Wang, Deyong Wang, Ziyu Zhang, Hongping Wang, Xianjie Zhou and Zhaofeng Zhu

Processes 2025, 13(3), 805; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030805 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

The turbidite lobe is a significant reservoir type formed by gravity flow. Analyzing the architecture of this reservoir holds great importance for deep-water oil and gas development. The main producing zone in Z Oilfield develops a set of turbidite lobes. After more than

[...] Read more.

The turbidite lobe is a significant reservoir type formed by gravity flow. Analyzing the architecture of this reservoir holds great importance for deep-water oil and gas development. The main producing zone in Z Oilfield develops a set of turbidite lobes. After more than 60 years of development, the well spacing has become dense, providing favorable conditions for detailed research on reservoir architecture of this kind. Based on seismic data, core data, and logging data, combined with the results of reservoir numerical simulation, this paper studies the reservoir architecture of turbidite lobes, displays the distribution of remaining oil in the turbidite lobes, and proposes development policies suitable for turbidite lobe reservoirs. The results show that the turbidite lobes can be classified into four sedimentary microfacies: lobe off-axis, lobe fringe, interlobe facies, and feeder channel facies. The study area is mainly characterized by multiple sets of lobes. There are feeder channels running through the south to the north. Due to the imperfect well pattern, the remaining oil is concentrated near the lobe fringe facies and the gas–oil contact. It is recommended to tap the potential of the turbidite lobes by adopting the “production at the off-axis lobes facies and injection at the lobe fringe facies (POIF)”. The study on the reservoir architecture and remaining oil of turbidite lobes has crucial guiding significance for the efficient development of Z Oilfield and can also provide some reference for developing deep-water oilfields with similar sedimentary backgrounds.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Flow Mechanisms and Enhanced Oil Recovery)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Location and structural characteristics of Z Oilfield. (<b>a</b>) Location of Z Oilfield; (<b>b</b>) Structural characteristics of Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Stratigraphic column of Illizi Basin (adapted from [<a href="#B47-processes-13-00805" class="html-bibr">47</a>]).</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Comprehensive colume of Formation B in Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Core photos of different sedimentary microfacies in Formation B of Z Oilfield (<b>a</b>). Core photos of the off-axis lobes facies in the Z1 well; (<b>b</b>) Core photos of the turbidite off-axis lobes facies in the Z1 well; (<b>c</b>) Core photos of the lobe fringe facies in the Z1 well; (<b>d</b>) Core photos of the feeder channels sedimentary facies in the Z2 well; (<b>e</b>) Core photos of the feeder channels sedimentary facies in the Z2 well.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Logging curves features for different sedimentary microfacies. (<b>a</b>) Logging curves features for different sedimentary microfacies in Well Z2; (<b>b</b>) Logging curves feature for different sedimentary microfacies in Well Z3.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Features of turbidite lobes in seismic data. (<b>a</b>) The seismic data for well section of Z4–Z9; (<b>b</b>) The RMS amplitude for well section of Z4–Z9.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Sedimentary features of turbidite lobes by using seismic data. (<b>a</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer IV; (<b>b</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer III; (<b>c</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer II; (<b>d</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer I.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Reservoir architecture in the perpendicular source direction in Formation B of Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Reservoir architecture along the source direction in Formation B of Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Numerical simulation results of profile remaining oil distribution in Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Numerical simulation of planar remaining oil reserve abundance in the Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Development strategy for the turbidite lobes. (<b>a</b>) Production at the off-axis lobes facies and injection in the lobe fringe facies; (<b>b</b>) Production at the lobe fringe facies and injection at the off-axis lobes facies.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z18 group zone. (<b>a</b>) Sectional distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z18 group zone; (<b>b</b>) Planar distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z18 group zone.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>The corresponding relationship between injecting Well Z17 and producing Well Z18.</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z19 group zone. (<b>a</b>) Sectional distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z19 group zone; (<b>b</b>) Planar distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z19 group zone.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>The corresponding relationship between injecting Well Z19 and producing Well Z20.</p> Full article ">

<p>Location and structural characteristics of Z Oilfield. (<b>a</b>) Location of Z Oilfield; (<b>b</b>) Structural characteristics of Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Stratigraphic column of Illizi Basin (adapted from [<a href="#B47-processes-13-00805" class="html-bibr">47</a>]).</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Comprehensive colume of Formation B in Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Core photos of different sedimentary microfacies in Formation B of Z Oilfield (<b>a</b>). Core photos of the off-axis lobes facies in the Z1 well; (<b>b</b>) Core photos of the turbidite off-axis lobes facies in the Z1 well; (<b>c</b>) Core photos of the lobe fringe facies in the Z1 well; (<b>d</b>) Core photos of the feeder channels sedimentary facies in the Z2 well; (<b>e</b>) Core photos of the feeder channels sedimentary facies in the Z2 well.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Logging curves features for different sedimentary microfacies. (<b>a</b>) Logging curves features for different sedimentary microfacies in Well Z2; (<b>b</b>) Logging curves feature for different sedimentary microfacies in Well Z3.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Features of turbidite lobes in seismic data. (<b>a</b>) The seismic data for well section of Z4–Z9; (<b>b</b>) The RMS amplitude for well section of Z4–Z9.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Sedimentary features of turbidite lobes by using seismic data. (<b>a</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer IV; (<b>b</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer III; (<b>c</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer II; (<b>d</b>) The RMS amplitude for layer I.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Reservoir architecture in the perpendicular source direction in Formation B of Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Reservoir architecture along the source direction in Formation B of Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Numerical simulation results of profile remaining oil distribution in Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Numerical simulation of planar remaining oil reserve abundance in the Z Oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Development strategy for the turbidite lobes. (<b>a</b>) Production at the off-axis lobes facies and injection in the lobe fringe facies; (<b>b</b>) Production at the lobe fringe facies and injection at the off-axis lobes facies.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z18 group zone. (<b>a</b>) Sectional distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z18 group zone; (<b>b</b>) Planar distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z18 group zone.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>The corresponding relationship between injecting Well Z17 and producing Well Z18.</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z19 group zone. (<b>a</b>) Sectional distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z19 group zone; (<b>b</b>) Planar distribution of reservoir permeability in Well Z19 group zone.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>The corresponding relationship between injecting Well Z19 and producing Well Z20.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Green Synthesis, Characterization, and Optimization of Chitosan Nanoparticles Using Blumea balsamifera Extract

by

Johann Dominic A. Villarta, Fernan Joseph C. Paylago, Janne Camille H. Poldo, Jalen Stephen R. Santos, Tricia Anne Marie M. Escordial and Charlimagne M. Montealegre

Processes 2025, 13(3), 804; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030804 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

Chitosan nanoparticles are nontoxic polymers with diverse biomedical applications. Traditional nanoparticle synthesis often involves harmful chemicals or results in reduced desirable properties, sparking interest in green synthesis methods for nanoparticle production. Utilizing plant-based phytochemicals as reducing and capping agents offers advantages like biocompatibility,

[...] Read more.

Chitosan nanoparticles are nontoxic polymers with diverse biomedical applications. Traditional nanoparticle synthesis often involves harmful chemicals or results in reduced desirable properties, sparking interest in green synthesis methods for nanoparticle production. Utilizing plant-based phytochemicals as reducing and capping agents offers advantages like biocompatibility, sustainability, and safety. This study explored Blumea balsamifera leaf extract for chitosan nanoparticle (CNP) synthesis. CNPs were synthesized using pH-induced gelation and characterized by DLS and SEM. B. balsamifera extract, prepared using ethanol, achieved a total phenolic content of 19.37 ± 6.35 mg GAE/g dry weight. DLS characterization revealed a broad size distribution, with an average particle diameter of 908.9 ± 93.6 nm and peaks at 11.11 ± 0.97 nm, 164.45 ± 6.13 nm, and 1672.04 ± 338.75 nm. SEM measurements showed spherical particles with a diameter of 56.8–63.0 nm. UV-Vis analysis, with an absorption peak at 286.5 ± 0.5 nm, was used to optimize CNP biosynthesis through a Face-Centered Central Composite Design (FCCCD). Higher concentrations of B. balsamifera extract (0.05 g/mL) and chitosan (19.1 mg/mL) maximized nanoparticle yield with a mass of 100 μg/mL. Antibacterial testing against E. coli demonstrated a minimum inhibitory concentration of 25 μg/mL. B. balsamifera extract effectively synthesized nanochitosan particles, showing potential for antibacterial applications.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Sustainable Innovation in the Production of Green Materials for Advanced Technologies)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Synthesized <span class="html-italic">B. balsamifera</span>-chitosan CNP suspension (<b>left</b>) and dried (<b>right</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Size distribution of CNPs through DLS.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p><span class="html-italic">B. balsamifera</span>-CNPs view from SEM.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>UV-Vis Spectra of CNPs showed a broad peak at 286.5 ± 0.5 nm.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Normal probability plot of residuals (<b>A</b>), Box–Cox plot for power transformation (<b>B</b>), and residual versus predicted (<b>C</b>) and the predicted versus actual (<b>D</b>) values of chitosan nanoparticle biosynthesis using <span class="html-italic">Blumea balsamifera</span> leaf extract.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Three-dimensional surface plot of absorbance as a function of chitosan and extract concentrations. (<b>A</b>) Optimization plot displaying the desirability function at the optimum predicted values (<b>B</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>The minimum inhibitory concentration for CNPs and Doxycycline was observed at the first dilution and eighth dilution, respectively.</p> Full article ">

<p>Synthesized <span class="html-italic">B. balsamifera</span>-chitosan CNP suspension (<b>left</b>) and dried (<b>right</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Size distribution of CNPs through DLS.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p><span class="html-italic">B. balsamifera</span>-CNPs view from SEM.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>UV-Vis Spectra of CNPs showed a broad peak at 286.5 ± 0.5 nm.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Normal probability plot of residuals (<b>A</b>), Box–Cox plot for power transformation (<b>B</b>), and residual versus predicted (<b>C</b>) and the predicted versus actual (<b>D</b>) values of chitosan nanoparticle biosynthesis using <span class="html-italic">Blumea balsamifera</span> leaf extract.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Three-dimensional surface plot of absorbance as a function of chitosan and extract concentrations. (<b>A</b>) Optimization plot displaying the desirability function at the optimum predicted values (<b>B</b>).</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>The minimum inhibitory concentration for CNPs and Doxycycline was observed at the first dilution and eighth dilution, respectively.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Study on Prediction of Wellbore Collapse Pressure of the Coal Seam Considering a Weak Structure Plane

by

Dongsheng Li, Kaiwei Cheng, Jian Li, Liang Xue and Zhongying Han

Processes 2025, 13(3), 803; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030803 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

To investigate the influence of weakly structured formations on wellbore stability in deep coal seams within the Lufeng Block, this study establishes an innovative predictive model for coal seam wellbore collapse pressure. The model integrates mechanical parameter variations along weak structural planes with

[...] Read more.

To investigate the influence of weakly structured formations on wellbore stability in deep coal seams within the Lufeng Block, this study establishes an innovative predictive model for coal seam wellbore collapse pressure. The model integrates mechanical parameter variations along weak structural planes with the Mohr–Coulomb criterion, leveraging experimental correlations between mechanical properties and bedding angle. Key findings reveal that the coal sample demonstrates enhanced compressive strength and elastic modulus under elevated confining pressures. A distinctive asymmetric “V” pattern emerges in mechanical parameter evolution: compressive strength, elastic modulus, cohesion, and internal friction angle initially decrease before recovering with increasing bedding angle, reaching minimum values at a 60° bedding angle. Comparative analysis demonstrates that the proposed model predicts a higher collapse pressure equivalent density than conventional Mohr–Coulomb approaches, particularly when accounting for mechanical parameter alterations along weak structural planes. Field validation through coal seam data from the operational well confirms the model’s effectiveness for stability analysis in weakly structured coal formations within the Lufeng Block. These findings provide critical theoretical support for wellbore stability management in deep coal seam engineering applications.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Environmentally Friendly Production of Energy from Natural Gas Hydrates)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

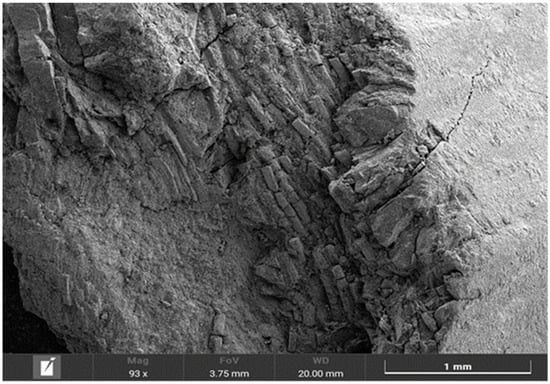

<p>100× scanning electron microscope.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>250× scanning electron microscope.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Comparison of elemental components in coal samples.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Coal sample for experiments. (<b>a</b>) Coal sample for nanoindentation experiment. (<b>b</b>) Standard cylindrical core.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 90°.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 30°.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 60°.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 0°.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Variation characteristics of mechanical parameters with bedding angle. (<b>a</b>) Elastic modulus. (<b>b</b>) Compressive strength. (<b>c</b>) Cohesion. (<b>d</b>) Internal friction angle.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Diagram of conversion relationship of wellbore coordinates.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Mohr–Coulomb weak plane strength criterion.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Coal seam wellbore stability model analysis flow.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Structure diagram of Lufeng oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Ground stress vertical profile.</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Vertical profile of uniaxial compressive strength.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>Map of the coal seam collapse pressure risk distribution.</p> Full article ">Figure 17

<p>Traditional Mohr–Coulomb prediction result. (<b>a</b>) Pore pressure and collapse pressure equivalent density based on traditional Mohr–Coulomb prediction. (<b>b</b>) Change of wellbore diameter during drilling.</p> Full article ">Figure 18

<p>Prediction results of our model.</p> Full article ">

<p>100× scanning electron microscope.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>250× scanning electron microscope.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Comparison of elemental components in coal samples.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Coal sample for experiments. (<b>a</b>) Coal sample for nanoindentation experiment. (<b>b</b>) Standard cylindrical core.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 90°.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 30°.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 60°.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Core stress-strain curve of 50 MPa confining pressure and bedding angle of 0°.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Variation characteristics of mechanical parameters with bedding angle. (<b>a</b>) Elastic modulus. (<b>b</b>) Compressive strength. (<b>c</b>) Cohesion. (<b>d</b>) Internal friction angle.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Diagram of conversion relationship of wellbore coordinates.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Mohr–Coulomb weak plane strength criterion.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Coal seam wellbore stability model analysis flow.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Structure diagram of Lufeng oilfield.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Ground stress vertical profile.</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Vertical profile of uniaxial compressive strength.</p> Full article ">Figure 16

<p>Map of the coal seam collapse pressure risk distribution.</p> Full article ">Figure 17

<p>Traditional Mohr–Coulomb prediction result. (<b>a</b>) Pore pressure and collapse pressure equivalent density based on traditional Mohr–Coulomb prediction. (<b>b</b>) Change of wellbore diameter during drilling.</p> Full article ">Figure 18

<p>Prediction results of our model.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Biochemical Methane Production Potential of Different Industrial Wastes: The Impact of the Food-to-Microorganism (F/M) Ratio

by

Ahmed El Sayed, Amr Ismail, Anahita Rabii, Abir Hamze, Rania Ahmed Hamza and Elsayed Elbeshbishy

Processes 2025, 13(3), 802; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030802 - 10 Mar 2025

Abstract

In this study, five distinct industrial waste streams, encompassing bakery processing and kitchen waste (BP plus KW) mixture, fat, oil, and grease (FOG), ultrafiltered milk permeate (UFWP), powder whey (PW), and pulp and paper (PP) compost, underwent mesophilic biochemical methane potential (BMP) assays

[...] Read more.

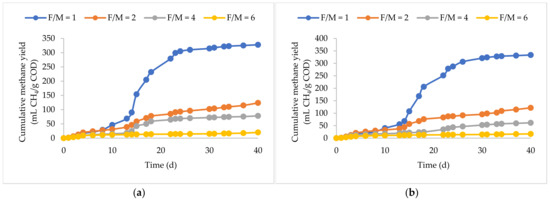

In this study, five distinct industrial waste streams, encompassing bakery processing and kitchen waste (BP plus KW) mixture, fat, oil, and grease (FOG), ultrafiltered milk permeate (UFWP), powder whey (PW), and pulp and paper (PP) compost, underwent mesophilic biochemical methane potential (BMP) assays at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6 g COD/g VSS. An F/M ratio of 1 g COD/g VSS showed the highest methane yield across the investigated feedstocks. In the case of UFPW and PW, an F/M ratio of 2 produced identical results to an F/M ratio of 1 despite their relatively high carbohydrate content which is easily acidified to VFAs. Increasing the F/M ratio to 2 decreased the biodegradability of both BP plus KW and FOG by 63%. Increasing the F/M ratio of the PP did not show as much of a significant impact on biodegradability compared to the other feedstocks as methane yields decreased from 135 to 92 mL CH4/g COD, a decrease of 32%.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Section Environmental and Green Processes)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Cumulative methane yields of (<b>a</b>) BP plus KW, (<b>b</b>) FOG, (<b>c</b>) UFWP, (<b>d</b>) PW, and (<b>e</b>) PP at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6.</p> Full article ">Figure 1 Cont.

<p>Cumulative methane yields of (<b>a</b>) BP plus KW, (<b>b</b>) FOG, (<b>c</b>) UFWP, (<b>d</b>) PW, and (<b>e</b>) PP at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Biodegradability of BP plus KW, FOG, UFWP, PW, and PP compost at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6.</p> Full article ">

<p>Cumulative methane yields of (<b>a</b>) BP plus KW, (<b>b</b>) FOG, (<b>c</b>) UFWP, (<b>d</b>) PW, and (<b>e</b>) PP at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6.</p> Full article ">Figure 1 Cont.

<p>Cumulative methane yields of (<b>a</b>) BP plus KW, (<b>b</b>) FOG, (<b>c</b>) UFWP, (<b>d</b>) PW, and (<b>e</b>) PP at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Biodegradability of BP plus KW, FOG, UFWP, PW, and PP compost at F/M ratios of 1, 2, 4, and 6.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Research on UAV Trajectory Tracking Control System Based on Feedback Linearization Control–Fractional Order Model Predictive Control

by

Keyong Shao, Wenjing Xia, Yujie Zhu, Chenjun Sun and Yang Liu

Processes 2025, 13(3), 801; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030801 - 9 Mar 2025

Abstract

Aiming at the problem of the nonlinear, strongly coupled, and underdriven trajectory tracking instability of a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), this thesis proposes a feedback linearization and fractional order model predictive control strategy based on feedback linearization by modeling the dynamics of

[...] Read more.

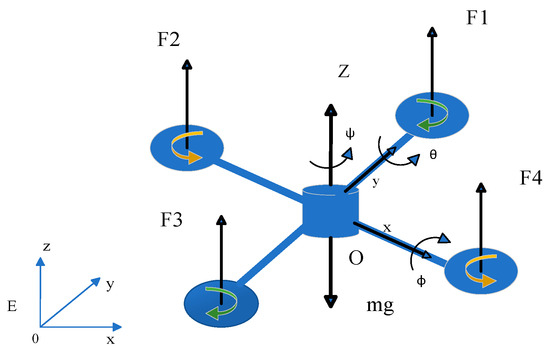

Aiming at the problem of the nonlinear, strongly coupled, and underdriven trajectory tracking instability of a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), this thesis proposes a feedback linearization and fractional order model predictive control strategy based on feedback linearization by modeling the dynamics of the UAV control system and linearizing the nonlinear model of attitude control. A dual closed-loop control structure, feedback linearization control (FLC) for a position loop, and fractional order model predictive control (FOMPC) for an attitude loop are adopted to realize fast position tracking and attitude response. In addition, considering that the fractional order method has the advantage of flexible regulation, the fractional order integral operator is added to the cost function of model predictive control. Finally, the simulation results and the calculation of the root mean square error verify that the proposed method has a fast response speed, small overshoot, stable flight, and good track tracking performance in UAV track tracking.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Section Automation Control Systems)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Structure of the quadrotor UAV.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Simple block diagram of quadcopter UAV control.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>UAV 3D path tracking curve.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>x-direction path tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>x-direction velocity tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>y-direction path tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>y-direction velocity tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>z-direction path tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>z-direction velocity tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Roll angle tracking.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Pitch angle tracking.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Yaw angle tracking.</p> Full article ">

<p>Structure of the quadrotor UAV.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Simple block diagram of quadcopter UAV control.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>UAV 3D path tracking curve.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>x-direction path tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>x-direction velocity tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>y-direction path tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>y-direction velocity tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>z-direction path tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>z-direction velocity tracking trajectory.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Roll angle tracking.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Pitch angle tracking.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Yaw angle tracking.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Numerical Analysis on Mechanical Properties of 3D Five-Directional Circular Braided Composites

by

Weiliang Zhang, Chunlei Li, Liang Li, Wei Wang, Lei Yang, Chaohang Zhang and Xiyue Zhang

Processes 2025, 13(3), 800; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030800 - 9 Mar 2025

Abstract

Based on the analysis of the motion law of 3D five-directional circular transverse braided fibers, this paper obtains the angle calculation formula between fibers and the local polar coordinate system in various cell models by transforming the position coordinates of fiber nodes. The

[...] Read more.

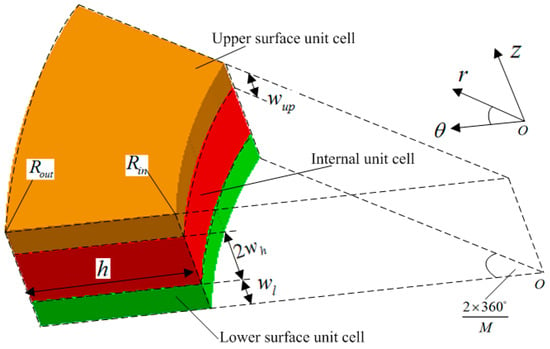

Based on the analysis of the motion law of 3D five-directional circular transverse braided fibers, this paper obtains the angle calculation formula between fibers and the local polar coordinate system in various cell models by transforming the position coordinates of fiber nodes. The stress transformation matrix between the local coordinate system and the global coordinate system of any fiber in the circular braided single cell is derived without considering the physical force on the single-cell micro-hexahedron unit. The calculation formulas of braided parameters such as the overall stiffness matrix and fiber volume content of the circular braided composite material after considering the matrix are derived by using the volume average method; the length of braided knuckles is 2 mm, the inner diameter of inner cells is 7 mm, the number of radial and axial braided yarns is 80, the height of inner cells is 0.5 mm, and the filling coefficient is 0.61. Comparing the results of the numerical prediction model with the experimental results in reference, it is found that the error of the numerical prediction model deduced in this paper is small. Therefore, this model can be used to fully study the effects of braided parameters such as cell inner diameter, cell height, and node length on the mechanical properties of composites.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Innovations in Manufacturing Processes and Systems for Sustainable Practices)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

Figure 1

<p>Three cell divisions.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Internal unit cell matrix and fiber.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Three-direction stress on inclined section perpendicular to <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>θ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> axis.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Three-direction stress on inclined section perpendicular to <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>z</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> axis.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Angle relationship of fibers in inner cell A.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Angle relationship of fibers in inner cell B.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Angle relationship of fiber in upper surface cells.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Angle relationship of fiber in lower surface cells.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Relationship curve between braiding angle and knuckle length.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Influence curve of cell height and knuckle length on fiber volume content and transverse elastic modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Influence curve of cell height and knuckle length on fiber volume content and longitudinal elastic modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Relationship curve of cell height, knuckle length, fiber volume content, and shear modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Influence curve of braiding parameters and transverse elastic modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Relationship curve between knuckle length and shear modulus under different yarn numbers.</p> Full article ">

<p>Three cell divisions.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Internal unit cell matrix and fiber.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Three-direction stress on inclined section perpendicular to <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>θ</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> axis.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Three-direction stress on inclined section perpendicular to <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <msub> <mi>z</mi> <mn>1</mn> </msub> </mrow> </semantics></math> axis.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Angle relationship of fibers in inner cell A.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Angle relationship of fibers in inner cell B.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Angle relationship of fiber in upper surface cells.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Angle relationship of fiber in lower surface cells.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Relationship curve between braiding angle and knuckle length.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Influence curve of cell height and knuckle length on fiber volume content and transverse elastic modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Influence curve of cell height and knuckle length on fiber volume content and longitudinal elastic modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Relationship curve of cell height, knuckle length, fiber volume content, and shear modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Influence curve of braiding parameters and transverse elastic modulus.</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Relationship curve between knuckle length and shear modulus under different yarn numbers.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessFeature PaperReview

Evolution of Dried Food Texturization: A Critical Review of Technologies and Their Impact on Organoleptic and Nutritional Properties

by

Freddy Mahfoud, Jessica Frem, Jean Claude Assaf, Zoulikha Maache-Rezzoug, Sid-Ahmed Rezzoug, Rudolph Elias, Espérance Debs and Nicolas Louka

Processes 2025, 13(3), 799; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030799 - 9 Mar 2025

Abstract

The evolution of food texturization techniques has opened new possibilities for producing healthy, ready-to-eat (RTE) snacks with improved sensory and nutritional properties. Originating from traditional methods such as deep frying and popping, the field has now embraced advanced technologies, including mechanical extrusion, puffing,

[...] Read more.

The evolution of food texturization techniques has opened new possibilities for producing healthy, ready-to-eat (RTE) snacks with improved sensory and nutritional properties. Originating from traditional methods such as deep frying and popping, the field has now embraced advanced technologies, including mechanical extrusion, puffing, Détente Instantanée Contrôlée (DIC), and the more recent Intensification of Vaporization by Decompression to the Vacuum (IVDV). These methods focus on enhancing texture and flavor and preserving nutritional value, while also prolonging shelf life, effectively meeting the increasing consumer demand for healthier snack options. This review explores the various food texturization methods, highlighting the key parameters for the optimization of organoleptic and nutritional properties. The strengths and limitations of each method were systematically evaluated and critically assessed. The development of innovative approaches for potential industrial applications, alongside efforts to mitigate the drawbacks of conventional methods, has become imperative. A comparative analysis was conducted, focusing on aspects such as productivity, efficacy, and operational conditions, demonstrating that the novel methods tend to be more environmentally sustainable and cost-effective while delivering the best-quality product in terms of texture, color, expansion factor, and nutritional content attributes.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Section Food Process Engineering)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

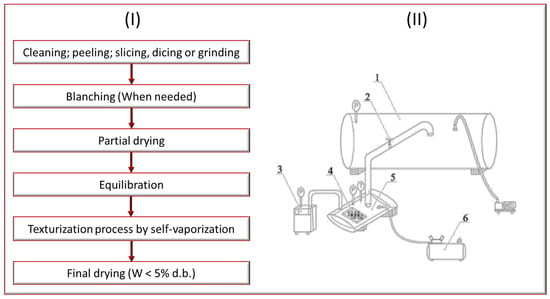

Figure 1

<p>(<b>I</b>) Schematic diagram of the global treatment involving texturization by self-vaporization. (<b>II</b>) Schematic diagram of explosion puffing drying device and accessories: 1, vacuum chamber; 2, decompression valve; 3, steam generator; 4, samples; 5, puffing chamber; 6, air compressor [<a href="#B121-processes-13-00799" class="html-bibr">121</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Photo of the DIC reactor: (I) processing vessel; (II) vacuum tank; (III) decompression valve [<a href="#B52-processes-13-00799" class="html-bibr">52</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Pressure–time profiles of IVDV (red), DIC (blue), and puffing (green) processing cycles: a, a’, a”: sample in the processing vessel at atmospheric pressure; b, b’: establishment of an initial vacuum within the treatment chamber (~0.1 s for IVDV and DIC); c, c’: sample under vacuum for a few seconds; d, d’, d”: steam generation (<1 s for IVDV and >1 s for DIC and puffing); e, e’, e”: processing at the selected pressure for a certain time; f, f’, f”: decompression duration (<1 s); g, g’: sample under vacuum for few seconds, with the possibility of air injection; h, h’: return to atmospheric pressure within the treatment chamber; i, i’, i”: sample recovery. Steps b’ and c’ are sometimes skipped during the DIC process.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Schematic diagram of the IVDV system: (<b>A</b>) treatment chamber; (<b>B</b>) steam generator; (<b>C</b>) vacuum tank; (<b>D</b>) ultra-speed pressure-increase system; (<b>E</b>) vacuum pump; v: valve.</p> Full article ">

<p>(<b>I</b>) Schematic diagram of the global treatment involving texturization by self-vaporization. (<b>II</b>) Schematic diagram of explosion puffing drying device and accessories: 1, vacuum chamber; 2, decompression valve; 3, steam generator; 4, samples; 5, puffing chamber; 6, air compressor [<a href="#B121-processes-13-00799" class="html-bibr">121</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Photo of the DIC reactor: (I) processing vessel; (II) vacuum tank; (III) decompression valve [<a href="#B52-processes-13-00799" class="html-bibr">52</a>].</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>Pressure–time profiles of IVDV (red), DIC (blue), and puffing (green) processing cycles: a, a’, a”: sample in the processing vessel at atmospheric pressure; b, b’: establishment of an initial vacuum within the treatment chamber (~0.1 s for IVDV and DIC); c, c’: sample under vacuum for a few seconds; d, d’, d”: steam generation (<1 s for IVDV and >1 s for DIC and puffing); e, e’, e”: processing at the selected pressure for a certain time; f, f’, f”: decompression duration (<1 s); g, g’: sample under vacuum for few seconds, with the possibility of air injection; h, h’: return to atmospheric pressure within the treatment chamber; i, i’, i”: sample recovery. Steps b’ and c’ are sometimes skipped during the DIC process.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>Schematic diagram of the IVDV system: (<b>A</b>) treatment chamber; (<b>B</b>) steam generator; (<b>C</b>) vacuum tank; (<b>D</b>) ultra-speed pressure-increase system; (<b>E</b>) vacuum pump; v: valve.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

Kinetics Study of Hydrogen Production by Aluminum Alloy Corrosion in Aqueous Acid Solutions: Effect of HCl Concentration

by

Ana L. Martínez-Salazar, Luciano Aguilera-Vázquez, Pedro M. García-Vite, Nelson Rangel-Valdez, Carlos Vega-Ortíz and Marco A. Coronel-García

Processes 2025, 13(3), 798; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030798 - 9 Mar 2025

Abstract

The current high cost of producing green hydrogen, for use as an energy vector, has motivated the search for the development of non-conventional technologies for its production, joining forces on the path towards energy transition. Hydrogen production by aluminum corrosion in aqueous acid

[...] Read more.

The current high cost of producing green hydrogen, for use as an energy vector, has motivated the search for the development of non-conventional technologies for its production, joining forces on the path towards energy transition. Hydrogen production by aluminum corrosion in aqueous acid solutions seems to be a promising alternative. In order to evaluate its technical feasibility, a kinetic study was carried out, analyzing the impact of HCl concentration (1.125 to 1.75 M) on the aluminum corrosion capacity under the presence of a saline environment and using a promoter, fitting the proposed models to the data obtained through experimental runs. Although other studies use the shrinking core model to describe the kinetics of this type of reaction, in most cases, it does not fit well with the experimental data and needs to be modified. Finally, by considering the corrosion dynamics (variations in diffusion coefficients and shell thickness) in the kinetic model equations, it was possible to describe its behavior. For low HCl concentrations, a single resistance controls the reaction of the particle throughout; however, for high HCl concentrations, a combination of related equations must be used. The results of this study enable viable continuous reactor designs for a given amount of green hydrogen production.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Special Issue 1st SUSTENS Meeting: Advances in Sustainable Engineering Systems)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

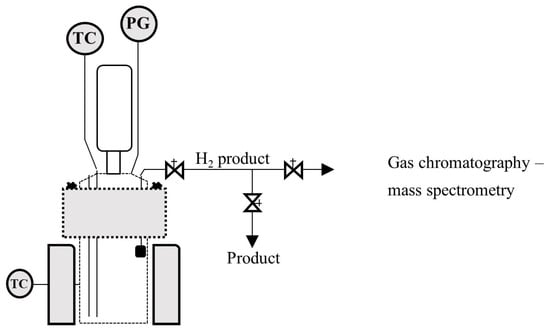

Figure 1

<p>Schematic of the hydrogen production reactive system.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Schematic of particle behavior during reaction.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>X-ray diffraction profile corresponding to the Na<sub>2</sub>MoO<sub>4</sub> synthesized.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>(<b>a</b>) UV–Vis absorption spectrum of molybdate ions (MoO<sub>4</sub><sup>−2</sup>); (<b>b</b>) particle sizes of Na<sub>2</sub>MoO<sub>4</sub> synthetized.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>(<b>a</b>) Hydrogen production rate vs. time; (<b>b</b>) temperature history, for different HCl molar concentrations in seawater (40.67 g aluminum, 0.17 M Na<sub>2</sub>MoO<sub>4</sub>).</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Results of developed models’ fit: diffusion through AlOOH layer controls the complete reaction, Equation (16), short-time model (diffusion through AlOOH layer controls), Equation (16), long-time model (chemical reaction controls), Equation (26); the experimental data obtained from reaction of HCl solution (<b>a</b>) 1.125 M; (<b>b</b>) 1.25 M; (<b>c</b>) 1.5 M; (<b>d</b>) 1.75 M and flat plate aluminum.</p> Full article ">Figure 6 Cont.

<p>Results of developed models’ fit: diffusion through AlOOH layer controls the complete reaction, Equation (16), short-time model (diffusion through AlOOH layer controls), Equation (16), long-time model (chemical reaction controls), Equation (26); the experimental data obtained from reaction of HCl solution (<b>a</b>) 1.125 M; (<b>b</b>) 1.25 M; (<b>c</b>) 1.5 M; (<b>d</b>) 1.75 M and flat plate aluminum.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Plots of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mfenced separators="|"> <mrow> <mn>1</mn> <mo>−</mo> <mfenced separators="|"> <mrow> <mn>1</mn> <mo>−</mo> <msub> <mrow> <mi>x</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>B</mi> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </mfenced> </mrow> </mfenced> </mrow> </semantics></math> versus reaction time in a linear relationship, Equation (26); the experimental data obtained from reaction of HCl solution (<b>a</b>) 1.25 M; (<b>b</b>) 1.5 M; (<b>c</b>) 1.75 M and flat plates aluminum with the long-time model (chemical reaction controls).</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Comparison between experimental and estimated conversion.</p> Full article ">

<p>Schematic of the hydrogen production reactive system.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Schematic of particle behavior during reaction.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>X-ray diffraction profile corresponding to the Na<sub>2</sub>MoO<sub>4</sub> synthesized.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>(<b>a</b>) UV–Vis absorption spectrum of molybdate ions (MoO<sub>4</sub><sup>−2</sup>); (<b>b</b>) particle sizes of Na<sub>2</sub>MoO<sub>4</sub> synthetized.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>(<b>a</b>) Hydrogen production rate vs. time; (<b>b</b>) temperature history, for different HCl molar concentrations in seawater (40.67 g aluminum, 0.17 M Na<sub>2</sub>MoO<sub>4</sub>).</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>Results of developed models’ fit: diffusion through AlOOH layer controls the complete reaction, Equation (16), short-time model (diffusion through AlOOH layer controls), Equation (16), long-time model (chemical reaction controls), Equation (26); the experimental data obtained from reaction of HCl solution (<b>a</b>) 1.125 M; (<b>b</b>) 1.25 M; (<b>c</b>) 1.5 M; (<b>d</b>) 1.75 M and flat plate aluminum.</p> Full article ">Figure 6 Cont.

<p>Results of developed models’ fit: diffusion through AlOOH layer controls the complete reaction, Equation (16), short-time model (diffusion through AlOOH layer controls), Equation (16), long-time model (chemical reaction controls), Equation (26); the experimental data obtained from reaction of HCl solution (<b>a</b>) 1.125 M; (<b>b</b>) 1.25 M; (<b>c</b>) 1.5 M; (<b>d</b>) 1.75 M and flat plate aluminum.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>Plots of <math display="inline"><semantics> <mrow> <mfenced separators="|"> <mrow> <mn>1</mn> <mo>−</mo> <mfenced separators="|"> <mrow> <mn>1</mn> <mo>−</mo> <msub> <mrow> <mi>x</mi> </mrow> <mrow> <mi>B</mi> </mrow> </msub> </mrow> </mfenced> </mrow> </mfenced> </mrow> </semantics></math> versus reaction time in a linear relationship, Equation (26); the experimental data obtained from reaction of HCl solution (<b>a</b>) 1.25 M; (<b>b</b>) 1.5 M; (<b>c</b>) 1.75 M and flat plates aluminum with the long-time model (chemical reaction controls).</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Comparison between experimental and estimated conversion.</p> Full article ">

Open AccessArticle

The Dynamic Mechanical Response of Anchored Fissured Rock Masses at Different Fissure Angles: A Coupled Finite Difference–Discrete Element Method

by

Guofei Chen, Haijian Su, Xiaofeng Qin and Wenbo Wang

Processes 2025, 13(3), 797; https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13030797 - 9 Mar 2025

Abstract

Anchored surrounding rock is prone to large nonlinear deformation and instability failure under dynamic disturbances. The fissures and defects within the surrounding rock make the rock mass’s bearing characteristics and deformation instability behavior increasingly complex. To investigate the effect of the fissure angle

[...] Read more.

Anchored surrounding rock is prone to large nonlinear deformation and instability failure under dynamic disturbances. The fissures and defects within the surrounding rock make the rock mass’s bearing characteristics and deformation instability behavior increasingly complex. To investigate the effect of the fissure angle on the dynamic mechanical response of the anchored body, a dynamic loading model of the anchored, fissured surrounding rock unit body was established based on the finite difference–discrete element coupling method. The main conclusions are as follows: Compared to the indoor test results, this numerical model can accurately simulate the dynamic response characteristics of the unit body. As the fissure angle increased, the dynamic strength, failure strain, and dynamic elastic modulus of the specimen generally decreased and then increased, with a critical angle at approximately 45°. Compared to 0°, when the fissure angle was 45°, the dynamic strength, failure strain, and dynamic elastic modulus decreased by 17.08%, 15.48%, and 9.11%, respectively. Additionally, the evolution process of cracks and fragments shows that the larger the fissure angle, the more likely cracks are to develop along the initial fissure direction, which then triggers the formation of tensile cracks in other regions. Increasing the fissure angle causes the specimen to rupture earlier, making the main rupture plane more directional.

Full article

(This article belongs to the Topic Advances in Coal Mine Disaster Prevention Technology)

►▼

Show Figures

Figure 1

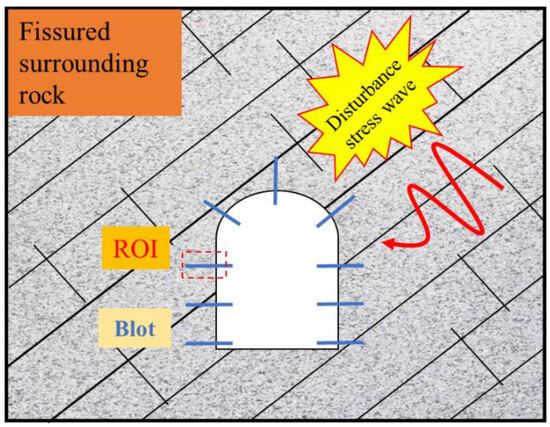

Figure 1

<p>Schematic diagram of anchored fissured surrounding rock tunnel under dynamic load disturbance.</p> Full article ">Figure 2

<p>Schematic diagram of an anchored, fissured rock mass element.</p> Full article ">Figure 3

<p>The Finite-Discrete coupling method: (<b>a</b>) coupling method; (<b>b</b>) schematic diagram of load transfer at the coupling interface.</p> Full article ">Figure 4

<p>SHPB dynamic impact numerical loading model.</p> Full article ">Figure 5

<p>Contact constitutive diagram: (<b>a</b>) parallel bond model; (<b>b</b>) smooth joint model.</p> Full article ">Figure 6

<p>(<b>a</b>) Displacement and strain contours of the anchor rod during the tensile test process; (<b>b</b>) numerical simulation results of the anchor rod tensile test.</p> Full article ">Figure 7

<p>(<b>a</b>) Incident stress curves at different dynamic loading velocities, (<b>b</b>) comparison of incident stress waves between numerical simulation and laboratory tests.</p> Full article ">Figure 8

<p>Model reliability verification: (<b>a</b>) axial stress distribution, (<b>b</b>) radial stress distribution, (<b>c</b>) rod-end contact force distribution.</p> Full article ">Figure 9

<p>Comparison of stress–strain curves from laboratory tests and numerical simulations for different specimens: (<b>a</b>) intact specimen, (<b>b</b>) fissured specimen, (<b>c</b>) anchored specimen.</p> Full article ">Figure 10

<p>Comparison of failure modes between indoor tests and numerical simulations for different types of specimens (note: in third row, yellow represents compression force chains, pink represents tension force chains, and blue represents cracks).</p> Full article ">Figure 11

<p>Stress–strain curves of anchored, fissured specimens at different fissure angles.</p> Full article ">Figure 12

<p>Variation in mechanical parameters with fissure angle.</p> Full article ">Figure 13

<p>Fracture process of anchored fissure specimens at different fissure angles: (<b>a</b>) 0°, (<b>b</b>) 30°, (<b>c</b>) 60° (The separated fragments are distinguished using different colors).</p> Full article ">Figure 14

<p>Crack propagation process of anchored fissure specimens at different fissure angles: (<b>a</b>) 0°, (<b>b</b>) 30°, (<b>c</b>) 60° (The blue represents tensile cracks, and the pink represents shear cracks).</p> Full article ">Figure 15

<p>Crack growth of anchored fissure specimens at different fissure angles: (<b>a</b>) 0°, (<b>b</b>) 30°, (<b>c</b>) 60°.</p> Full article ">Figure 16