Together with Made in Nature, we explored at the Macfrut fair in Rimini, the Italian organic fruit and vegetable market and its key players.

On the hills of Minabe and Tanabe ume fruit has been cultivated alongside oak forests and honeybees for centuries using a method now recognised by the FAO.

Japan is famous for the springtime blooming of sakura cherry trees. Equally delightful in late winter (in February and early March) is the sight of hillsides carpeted in the pink flowers of another tree, ume, the Japanese apricot often mistakenly labelled as a plum.

Yet, unlike sakura, this is much more than just a pretty flower. As a fruit, ume can be transformed into anything from a liquor known as umeshu to syrup and jam, and in its salted, pickled version of umeboshi it is a quintessential Japanese staple consumed as a side dish and condiment.

Foodies around the world have also started embracing ume’s sour, umami-rich flavour: in 2022, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on a boom in ume infused products in California. Contributing to the fruit’s popularity are also its health properties ranging from curing hangovers to high levels of potassium and the presence of polyphenols that boost immune defences.

Over half of Japan’s ume production can be credited to two small towns, Minabe and Tanabe, in the western prefecture of Wakayama. Of the 80,000 people who call these home, a staggering 70% work in ume related jobs.

At the core of this ume infused economy are centuries-old sustainable agricultural practices in which different elements of a wide ecosystem interact as a unified whole, allowing for a healthy farming output as well as for preserving biodiversity and water resources.

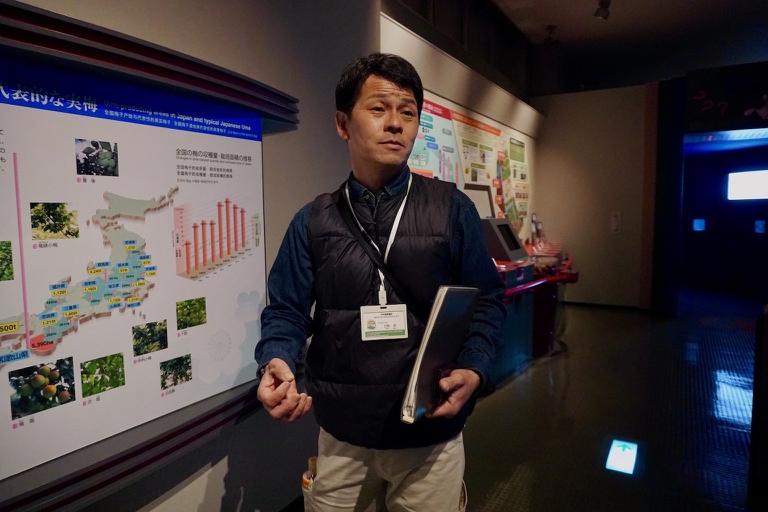

“The coexistence between these elements, namely ume orchards, coppice forests and pollinators, was officially recognised by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in 2015,” says Akira Ueno, an ume farmer and team leader of Minabe’s Machi Campus Project, which educates young people about this area’s socio-environmental landscape.

In these respects, the Minabe-Tanabe Ume System has something in common with agricultural communities in 24 countries around the globe, including Soave winemakers in north-eastern Italy, Maasai pastoralists in Kenya, and Andean farmers in Ecuador and Peru: it is one of 74 Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS), a designation assigned by the FAO to “living, evolving system(s) of human communities in an intricate relationship with their territory, cultural or agricultural landscape or biophysical and wider social environment”.

Ume’s roots, however, run much deeper than the GIAHS recognition . The prunus mume tree was first brought to Japan from China between 1,500 and 2,000 years ago and for a long time its fruits were consumed as medicine and only by the upper classes. It wasn’t until four centuries ago, during the Edo Period (1603-1868), that umeboshi made its way into Japanese people’s daily diets.

In Edo-era Japan farmers used to pay taxes to their feudal lords in the form of rice. However, Minabe and Tanabe’s steep slopes and muddy soil, which don’t retain water well, make this area unsuitable for rice cultivation. In 1620, lord Naotsugu Ando encouraged farmers to plant ume, which grew wild, instead: not only did locals start paying taxes in ume rather than rice, but this intuition sowed the seeds of Japan’s ume craze.

Fast-forward to the 1960s and the Nanko ume variety, first identified and registered in this area, sealed Minabe and Tanabe’s fate. This variety is one of Japan’s most popular and makes up 83 per cent of Minabe and Tanabe’s production, which was worth 94 million dollars (US) in 2012. It is also the finest for making umeboshi because of its thin skin and soft, abundant pulp.

To this day, yearly festivals are held in Minabe and Tanabe to give thanks for the harvest of Nanko and other locally cultivated varieties, for a total of 23. One such festivity is “Ume Day” on 6 June, when ume is offered in several Shinto shrines – including Minabe’s most ancient, Suga Jinja, which is over 1,000 years old – on the same day the Japanese Emperor undertook this ritual in a Kyoto shrine in 1545. Ume Day is taken so seriously that a local law in Minabe establishes that residents must eat umeboshi flavoured onigiri, or rice balls, for the occasion.

As well as a myriad local customs related to ume, the agricultural methods that have developed in Minabe and Tanabe over the last 400 years have been maintained and refined over time. At their core is the interconnectedness between different parts of the ume system.

Starting from the top, the mountain ridges above ume orchards are covered in coppice forests in which “selective cutting is practised, meaning that old branches are pruned to allow new ones to grow,” Ueno explains. An oak species called ubame that lives in these forests is used to produce a type of high-grade charcoal, Kishu Binchotan, that this region is famous for.

By cutting only branches, tree roots are preserved and this helps prevent slope collapse and allows water to be released slowly into the ground, replenishing groundwater sources. “The water then flows downhill, through the orchards to the river and valleys below,” Ueno says, feeding other forms of agriculture.

Notable among these is ume cultivation. In the orchards, a method called sod culture is practised whereby grasses are allowed to grow beneath ume trees, making the hillsides not only beautifully pink in the flowering season, but lusciously green too. As well as maintaining good moisture levels in the soil, sod culture prevents pests from attacking trees as insects tend to stay in the grasses below, Ueno explains.

Even more crucially, the grasses and ume flowers attract honeybees, whose preservation isn’t only a source of local pride but a matter of necessity. Ume varieties such as Nanko can’t pollinate themselves so different varieties are grown alongside each other and cross-pollination occurs thanks to the precious insects. While ume production in Minabe and Tanabe isn’t necessarily organic, Ueno points out that “we don’t spray pesticides in the flowering period as this is when the bees are active”.

When it comes to harvesting Nanko ume from May to July, the best method is to wait for the fruits to fall once they’re ripe, which is when they’re sweetest. Together with nets placed under trees, grasses act as a cushion for falling ume.

This interdependent ecological and agricultural system leads not only to a balanced approach to farming but to the proliferation of many animal species. Eurasian sparrowhawks, northern goshawks and other birds live in ume orchards and coppice forests, and rare species such as the Mitsjama salamander and Japanese fire-bellied newt have been seen in irrigation ponds and valleys in lowland areas.

“This system was already in place well before the GIAHS designation, but thanks to this recognition farmers can now see it clearly for what it is,” says Ueno. For example, charcoal and ume producers are more aware of just how much their work depends on each other.

“(Also), the GIAHS label doesn’t only acknowledge that we’re applying ancient agricultural techniques, but our ability to adapt these to future generations’ needs,” the ume farmer adds. “The designation has also made it easier to explain our system to young people”. As the leader of the Machi Campus Project, Ueno is devoted to bringing university students into ume farms to learn about their unique characteristics with the longterm goal of getting these students to teach those younger than them.

“Some farmers tell their children to choose a different profession, but I’m doing the opposite,” he says. “I want to get the next generation involved.”

Ueno’s vision is essential for the survival of Minabe and Tanabe’s ume system. Notwithstanding the GIAHS recognition, ume production is suffering due to rural communities’ shrinking and ageing. Another issue is “falling demand for ume products because of the westernisation of Japanese diets”.

One potential solution would be to target exports more, Ueno says. The high quality of one of Japan’s most beloved fruits and the careful way in which it is grown could be important selling points when it comes to expanding ume’s reach abroad. The goal isn’t only to secure the livelihoods of communities embedded in the ume system but reward agricultural products that sustain local cultures and environmental well-being.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Together with Made in Nature, we explored at the Macfrut fair in Rimini, the Italian organic fruit and vegetable market and its key players.

Made in Nature is a project funded by the European Union and Cso Italy to promote the benefits of organic food consumption for our health and that of the environment.

The revival of millet farming has been tackling malnutrition and improving the livelihoods of Kutia Kondh tribespeople in Odisha state, in eastern India.

The same tycoons who created factory farms are the ones investing in fake meat. But “real” food can’t be created in laboratories: regenerative agriculture is the only way.

Through the Moments Not To Be Wasted educational project and the Talent Kitchen contest, Whirlpool teaches schoolchildren about food waste in a rewarding and inclusive way.

Food waste is a serious problem and we’re paying a dear price for it, but the European Union has many ideas on how to stop it.

Chef Vikas Khanna has been coordinating efforts to feed migrants in desperate conditions due to the coronavirus lockdown in India. A story of compassion.

Factory farming conditions and antibiotic-resistant pathogens emerging as a result of them pose an existential threat to humans in the form of zoonotic diseases. Why it’s time to produce and consume food more thoughtfully.

The world of cinema recognises the link between food choices and the climate crisis by offering vegan menus for awards season events, including at the most important of them all: the Oscars.