IMDb RATING

7.5/10

3.7K

YOUR RATING

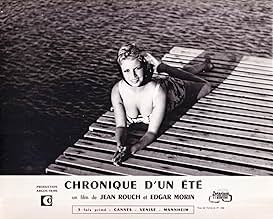

A documentary about the everyday lives of ordinary Parisians, done in the style of cinéma vérité.A documentary about the everyday lives of ordinary Parisians, done in the style of cinéma vérité.A documentary about the everyday lives of ordinary Parisians, done in the style of cinéma vérité.

- Awards

- 1 win

Marceline Loridan Ivens

- Self

- (as Marceline)

Marilù Parolini

- Self

- (as Mary Lou)

Jean-Pierre Sergent

- Self

- (as Jean-Pierre)

Jacques Gautrat

- Self - un ouvrier

- (as Jacques)

Régis Debray

- Self - un étudiant

- (as Régis)

Nadine Ballot

- Self

- (as Nadine)

Modeste Landry

- Self - un étudiant africain

- (as Landry)

Jacques Gabillon

- Self - un employé

- (as Jacques)

Simone Gabillon

- Self - une employée

- (as Simone)

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaThe 6th greatest documentary of all time according to the 'Sight & Sound' poll 2014. The list was compiled after polling from over 200 critics and curators and 100 filmmakers.

- Quotes

Sophie - the cover-girl: People are bored everywhere now. But boredom comes from within. If you've got an inner life, you're never bored.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Les échos du cinéma: Episode #1.23 (1961)

Featured review

This is a magnificent, and exquisitely sensitive and original, film which I never saw until now. It has been released on DVD with an extremely informative and lengthy booklet by Sam di Iorio, and with many DVD extras (such as previously unseen footage cut from the original officially released version of this film) and important and informative interviews. It is necessary to see it all and read the booklet in order to take in the enormous importance of this project, and its effect on worldwide film-making which followed afterwards. The film was jointly directed by ethnographic film-maker Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin, the latter being a sociologist and intellectual. I knew Jean Rouch during the latter 1970s. He was employed by the Ethnographic Film Unit of the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. I was introduced to him by an anthropologist with whom he worked closely, Germaine Dieterlen. The fact that I was friendly with his anthropologist colleagues (including also Solange de Ganay and the family of Dominique Zahan) and came to him in that way rather than through the media meant that he was particularly warm and friendly towards me and was prepared to give me every cooperation. He was a truly marvellous man, and if I had lived in Paris I would inevitably have been drawn into his fascinating circle of friends. I was at the time working under a contract with the BBC on a major TV documentary, not only as a researcher, but effectively as a co-producer for much of it, though uncredited as such. We needed ethnographic footage from Jean of a West African tribe. But Jean had eccentric personal habits and was exasperatingly elusive. This was long before cellphones existed. He would leave his flat every morning (except for the times when he stayed out all night) between 7 and 8 AM and could not then be contacted by any telephone. That is of course 6 to 7 AM British time. No BBC employee is awake at such an hour, much less in the office. So the BBC gave me the additional assignment of dealing with Jean Rouch entirely on my own, up until financial negotiations were reached. I would set my alarm clock for 5 AM and try and become alert enough to phone him before 6. In Paris, Jean and I sat through about 36 hours of ethnographic footage together and had long talks. During this time I conceived an enormous respect and admiration for him, but I never had any idea that he had made this film, and he never mentioned it. I now know that he had been greatly influenced by WE ARE THE LAMBETH BOYS (1958), which I had seen and admired long before, and which was an early documentary by the British director Karel Reisz, under whom I had apprenticed for several months in the 1960s. (I don't believe Karel and Jean ever met, which is a pity.) But as I was unaware of Rouch's non-ethnographic film-making, we never discussed Karel's work, which would have been so interesting for both of us. Jean was infatuated with his Africans, and only wanted to talk about them, and we bonded because of sharing that interest. This film shot in the summer of 1960 was a 'revolution in the cinema' in the true sense. The film set out to ask people 'are you happy?' and got some dusty answers. Although a few strangers were approached in the street on a vox pop basis, most of the people interviewed were individuals known to the directors. Some of the interviews are overwhelmingly emotional, more powerful and devastating to watch than any dramatic acting. The two main examples of this are the scenes with the amazing Marceline Loridan, who years later married the documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, and is still very much alive, as well as with 'Mary Lou' (really Marilu) Parolini. Towards the end of the film she is glowing with happiness because she has found a boyfriend whom she loves. He is Jacques Rivette, later a famous film director. Another famous person who appears in the film as a young man is the notorious ideologue and political provocateur Régis Debray, who became a friend and colleague of Che Guevara. So fascinating is this film and everything connected with it that a review can do it no justice at all. But what is most remarkable of all is the intensity of many of the film's sequences, perhaps because they are real rather than simulated, and come from people prepared to be more honest and revealing about themselves in front of a camera than possibly anyone had ever been before. It is in this sense that this film goes beyond all previous horizons and treads a New Land, as unexplored by the cinema until then as the subconscious had been before Freud. The monologue spoken on the sound track by Marceline, as she wanders through the now-vanished Les Halles, about her memories of Auschwitz, where she had been taken as a Jewish girl of 16, and of her last meeting there with her father, who had told her she would get out of there but he would not, are so distressing that they would bring tears to the eyes of stones, if they could see and hear. But the most torrential outpouring of emotions comes from Marilu Parolini, and her self-revelations must rank amongst the most harrowing and naked in the entire history of film. It is impossible to overestimate the importance of this shattering documentary, not only for the history of cinema, but as a breakthrough in the moral, social, and psychological spheres. It was the first film of the cinema verité movement, which it founded. And since then, it is doubtful that any other film of this kind has yet equalled it. Let us hope therefore that this DVD release may stimulate more projects like it.

- robert-temple-1

- Jul 27, 2013

- Permalink

- How long is Chronicle of a Summer?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Runtime1 hour 25 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content