Un vétéran de la guerre civile américaine se lance dans une expédition visant à délivrer sa nièce des Comanches.Un vétéran de la guerre civile américaine se lance dans une expédition visant à délivrer sa nièce des Comanches.Un vétéran de la guerre civile américaine se lance dans une expédition visant à délivrer sa nièce des Comanches.

- Prix

- 4 victoires et 4 nominations au total

Patrick Wayne

- Lt. Greenhill

- (as Pat Wayne)

Avis en vedette

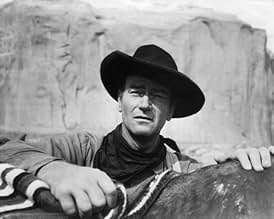

John Ford is a classic Western filmmaker (though certainly not the only genre in which he excelled), employing the classic Western film star, John Wayne, in perhaps one of the most underappreciated films of our time. Ford builds a thoroughly entertaining movie which explores classic Western themes without necessarily relying on these themes to drive the plot.

Like any good Western, we are inorexably drawn to a kind of Cowboys vs. Indians saga, but Ford manages to draw us into the conflict in such a way that the mere "Cowboys good, Indians bad" aesthetic isn't really applicable here. While relying on the archetypical roles of the two groups to set up a conflict, Ford is ahead of his time in managing to characterize the Indians as more than "noble savages". Wayne's character's (Ethan Edwards) hatred of "the Commanch" is called into question a number of times, especially in his stormy relationship with adopted nephew and fellow searcher Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), who we are told is a quarter-Indian himself, and cannot bring himself to find the same sort of hatred for the Indians that Ethan holds.

Ethan was a Confederate soldier in the Civil War, returning to his brother's Texas homestead after the war. A group of Commanches, led by the ominous Chief Scar, route and kill his brother's family while Ethan and Martin are investigating a cattle rustling, the Commaches' diversionary tactic. The Indians took the family's youngest daughter, and the majority of the film has us following Ethan and Martin in their attempts to track down Scar and take back the girl, Debbie (played by Lorna and Natalie Wood, at different times).

Such a situation sets up one of the many moral ambiguities that make this more than an ordinary Western: the Commanches slaughtered Ethan's brother and his family - he seemingly has reason to hate them with the almost crazy passion that he does. Yet the more naive Martin cannot bring himself to hate them in such a way, and the split between them becomes a major point of contention when it becomes clear that Debbie has more or less been adopted as a Commanche (the two "Searchers" chase after her for about five years in film time). Furthermore, when the two "Searchers" actually meet Scar, who they've been chasing for years, he is presented as a rather intelligent character, although certainly one filled with vengance - he, too, has his reasons for waging war with the likes of Ethan and Martin, and cannot merely be written off a the type of bloodthirsty savage that is typical of the portrayal of most Indians within the genre.

The film relies on enough classic Western material to imbue with the feel with the sense of such pictures. Aside from the question of Ethan's morality, Wayne plays him with classic John Wayne freewheeling confidence and swagger that made the actor such an icon, and it comes off quite well. We are also given a side story involving Martin's romance with the hard-as-nails Laurie Jurgensen (played by Vera Miles, best known for playing Janet Leigh's sister in "Psycho"). The relationship is from a classic, archetypical Western mold - the two have been in love since they were kids, but Martin has responsibilites to his family that stop him from making the proper time for his beau, and his rough frontier-uprbringing leave him seemingly lacking the proper sensitivity for dealing with Laura (though he does, of course, have a heart of gold).

As a side note, this film should prove immensely interesting to any serious fan of the "Star Wars" trilogy (the original one). While those films undoubtably draw a great deal of inspiration from Kurosawa's samurai films, there is most certainly a great deal (especially in the film subtitled "A New Hope") drawn from here. One scene in particular (when Luke returns to his farm after stormtroopers have blasted in pieces) is virtually ripped straight from "The Searchers". Ford's film is also full of the sort of gallows humor present throughout the trilogy, and even incorporates some rather goofy characters, the half-cracked Mose Harper (Hank Warden) and the incredibly over-the-top rival for Laura's hand Charlie McCorry (Ken Curtis), without ruining the overall serious feel of the film, but managing to squeeze laughs out of absurd situations (such as a fight between Martin and Charlie) without compromising the ability to quickly return to a solemn tone. Such deft touch, as well as the addition of wise-cracking dialogue (provided largely by Wayne and Ward Bond here) are a large part of what made the original trilogy so successful, and it's strikingly similar to the type of paradigm on display between various characters here.

Regardless of ranting and raving about Star Wars, however, this is an excellent film on it's own merit.

Like any good Western, we are inorexably drawn to a kind of Cowboys vs. Indians saga, but Ford manages to draw us into the conflict in such a way that the mere "Cowboys good, Indians bad" aesthetic isn't really applicable here. While relying on the archetypical roles of the two groups to set up a conflict, Ford is ahead of his time in managing to characterize the Indians as more than "noble savages". Wayne's character's (Ethan Edwards) hatred of "the Commanch" is called into question a number of times, especially in his stormy relationship with adopted nephew and fellow searcher Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), who we are told is a quarter-Indian himself, and cannot bring himself to find the same sort of hatred for the Indians that Ethan holds.

Ethan was a Confederate soldier in the Civil War, returning to his brother's Texas homestead after the war. A group of Commanches, led by the ominous Chief Scar, route and kill his brother's family while Ethan and Martin are investigating a cattle rustling, the Commaches' diversionary tactic. The Indians took the family's youngest daughter, and the majority of the film has us following Ethan and Martin in their attempts to track down Scar and take back the girl, Debbie (played by Lorna and Natalie Wood, at different times).

Such a situation sets up one of the many moral ambiguities that make this more than an ordinary Western: the Commanches slaughtered Ethan's brother and his family - he seemingly has reason to hate them with the almost crazy passion that he does. Yet the more naive Martin cannot bring himself to hate them in such a way, and the split between them becomes a major point of contention when it becomes clear that Debbie has more or less been adopted as a Commanche (the two "Searchers" chase after her for about five years in film time). Furthermore, when the two "Searchers" actually meet Scar, who they've been chasing for years, he is presented as a rather intelligent character, although certainly one filled with vengance - he, too, has his reasons for waging war with the likes of Ethan and Martin, and cannot merely be written off a the type of bloodthirsty savage that is typical of the portrayal of most Indians within the genre.

The film relies on enough classic Western material to imbue with the feel with the sense of such pictures. Aside from the question of Ethan's morality, Wayne plays him with classic John Wayne freewheeling confidence and swagger that made the actor such an icon, and it comes off quite well. We are also given a side story involving Martin's romance with the hard-as-nails Laurie Jurgensen (played by Vera Miles, best known for playing Janet Leigh's sister in "Psycho"). The relationship is from a classic, archetypical Western mold - the two have been in love since they were kids, but Martin has responsibilites to his family that stop him from making the proper time for his beau, and his rough frontier-uprbringing leave him seemingly lacking the proper sensitivity for dealing with Laura (though he does, of course, have a heart of gold).

As a side note, this film should prove immensely interesting to any serious fan of the "Star Wars" trilogy (the original one). While those films undoubtably draw a great deal of inspiration from Kurosawa's samurai films, there is most certainly a great deal (especially in the film subtitled "A New Hope") drawn from here. One scene in particular (when Luke returns to his farm after stormtroopers have blasted in pieces) is virtually ripped straight from "The Searchers". Ford's film is also full of the sort of gallows humor present throughout the trilogy, and even incorporates some rather goofy characters, the half-cracked Mose Harper (Hank Warden) and the incredibly over-the-top rival for Laura's hand Charlie McCorry (Ken Curtis), without ruining the overall serious feel of the film, but managing to squeeze laughs out of absurd situations (such as a fight between Martin and Charlie) without compromising the ability to quickly return to a solemn tone. Such deft touch, as well as the addition of wise-cracking dialogue (provided largely by Wayne and Ward Bond here) are a large part of what made the original trilogy so successful, and it's strikingly similar to the type of paradigm on display between various characters here.

Regardless of ranting and raving about Star Wars, however, this is an excellent film on it's own merit.

A second look at this film is long overdue. It's been hailed by many as a masterpiece. Even the anti-Ford critic David Thomson in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film classifies it as an exceptional work. I don't know whether it's the Ford mystique, the Wayne icon, or the mesmerizing beauty of Monument Valley that holds this movie to a different standard from most Westerns. But something is at work that numbs a critical eye-level inquiry. The Searchers is a good film, but no masterpiece, and certainly does not belong in the American Film Institute's list of top 100 films of all time. A brief look at some of the more obvious defects:

Ford makes picture postcards out of the soaring spires and buttes. At no point, however, does he come to grips with the real harshness of the terrain. This is desert country. Hardly anything grows-- just look at the sparseness of greenery. Yet we're told cattle herds feed here in large enough numbers to support families, (In the movie, Jorgensen's right-- they would be better off raising pigs than cattle). Then too, there is absolutely no hint of the desert heat or cold affecting anything or anybody. The parties go here and there with slim regard for what the conditions actually afford. In short, the celebrated landscape amounts to little more than a majestic backdrop without a true reality of its own. Ford may love this Spartan terrain, but he gives it scant respect.

Similarly, the film-maker undercuts the naturalism of the vaunted visuals. The audience gets an awesome flow of natural wonders, only to have the flow interrupted by outdoor sets so painfully obvious, they can't be ignored, (consider the Futterman ambush scene, for one). As a result, visual continuity is sacrificed and so is fidelity to the intended atmosphere. Suddenly we're jolted out of the scenic spell back into recognition that this is, after all, only a movie. Where, one wonders, was Ford's very real poetic eye in these disruptive scenes, and why didn't he insist on shooting all outdoor scenes outdoors-- especially after traveling to Colorado for the great snow scenes. As a premier film-maker, I'm sure he had the clout. Nonetheless, the lapse is another glaring defect.

There's another problem with respect, this time for the adversary. In fact, the Indians do get some concessions--Scar is provided a moment of motivation and a good sarcastic aside-- but not much else. As in Ford's cavalry cycle, aboriginal peoples still exist as convenient devices and sitting ducks. From the film's several battles, it seems the Indians know nothing about combat tactics. Stupidly, they never attack unless an escape route is left open to the fleeing settlers. And when they attack frontally across the river or in front of the cave, they mass in a bunch so the dug-in whites can hardly miss. No wonder there are so few Indians left. In most Westerns, this cliché would not even merit comment, but remember this one's supposed to be a "masterpiece".(For a gauge of Ford's dishonesty, compare his cardboard warriors with the skilled and savvy combatants in the similarly themed "Ulzana's Raid" {1973}).

For what is required of the actors, contrast the first ten minutes with the movie's remainder. Those first few minutes are little short of superb. There's a low-key naturalism and subtlety that's fascinating-- Just who is Ethan Edwards? What is the tension between his brother and him? And where did he get that impressive war medal? The well-crafted impression is that of real people concealing true feelings, while groping toward some kind of reconciliation across unspoken barriers. Then Ward Bond and the posse arrive and slam-bang stereotypes take over. The promising beginning is lost, while Ford reverts to form by replacing character with caricature. Bond, for example, stands not just as a gruff old man, but as The Gruff Old Man; Jeffrey Hunter is not just a callow youth, but The Callow Youth; and most egregiously, Ken Curtis is not merely one more country yokel, but The Rub-your-Nose-In-It Country Yokel. Moreover, conversation ceases, hat-throwing and shouting take over, and genuine interaction gives way to exaggerated personalities doing little more than bouncing off one another. Even Wayne's one-note avenger comes close to parody, (unlike others, however, he is never mocked). Of course, such caricatures provide ample grist for Ford's broad idea of humor. Nonetheless, the comic set-ups come perilously close at times to a Three Stooges level, particularly the scenes with Old Mose, and with Bond and Patrick Wayne. I'm not against comic relief, but I am when it flirts with burlesque in an otherwise serious film.

More could be pointed out, such as the distracting subplots, or the ludicrous wedding sequence, or most glaringly, the climax with its sudden, unmotivated change of heart-- after all, it's the racial conflict that drives the plot. I guess what really bothers me is how blithely Ford substitutes his own highly simplistic vision of the Old West for any really plausible version. There's a basic lack of respect for the material, which allows, for example, such facile touches as Jorgensen's unweathered two-story wooden house in the middle of the desert, or Vera Miles' brocaded form-fitting wedding gown that appears to have been flown in from Paris. My point is not that the film lacks merit-- the justly celebrated doorway shots, for example. Rather, it's one of perspective-- this is an entertaining film but far from a masterpiece.The Searchers may be lauded and popular with many. Nonetheless, beneath the glossy surface lies an under-developed theme that really deserved better than standard stock company treatment. In short, Thomson is wrong. The Searchers is not an exception to Ford's usual product. Rather, it's just a little less compromised.

Ford makes picture postcards out of the soaring spires and buttes. At no point, however, does he come to grips with the real harshness of the terrain. This is desert country. Hardly anything grows-- just look at the sparseness of greenery. Yet we're told cattle herds feed here in large enough numbers to support families, (In the movie, Jorgensen's right-- they would be better off raising pigs than cattle). Then too, there is absolutely no hint of the desert heat or cold affecting anything or anybody. The parties go here and there with slim regard for what the conditions actually afford. In short, the celebrated landscape amounts to little more than a majestic backdrop without a true reality of its own. Ford may love this Spartan terrain, but he gives it scant respect.

Similarly, the film-maker undercuts the naturalism of the vaunted visuals. The audience gets an awesome flow of natural wonders, only to have the flow interrupted by outdoor sets so painfully obvious, they can't be ignored, (consider the Futterman ambush scene, for one). As a result, visual continuity is sacrificed and so is fidelity to the intended atmosphere. Suddenly we're jolted out of the scenic spell back into recognition that this is, after all, only a movie. Where, one wonders, was Ford's very real poetic eye in these disruptive scenes, and why didn't he insist on shooting all outdoor scenes outdoors-- especially after traveling to Colorado for the great snow scenes. As a premier film-maker, I'm sure he had the clout. Nonetheless, the lapse is another glaring defect.

There's another problem with respect, this time for the adversary. In fact, the Indians do get some concessions--Scar is provided a moment of motivation and a good sarcastic aside-- but not much else. As in Ford's cavalry cycle, aboriginal peoples still exist as convenient devices and sitting ducks. From the film's several battles, it seems the Indians know nothing about combat tactics. Stupidly, they never attack unless an escape route is left open to the fleeing settlers. And when they attack frontally across the river or in front of the cave, they mass in a bunch so the dug-in whites can hardly miss. No wonder there are so few Indians left. In most Westerns, this cliché would not even merit comment, but remember this one's supposed to be a "masterpiece".(For a gauge of Ford's dishonesty, compare his cardboard warriors with the skilled and savvy combatants in the similarly themed "Ulzana's Raid" {1973}).

For what is required of the actors, contrast the first ten minutes with the movie's remainder. Those first few minutes are little short of superb. There's a low-key naturalism and subtlety that's fascinating-- Just who is Ethan Edwards? What is the tension between his brother and him? And where did he get that impressive war medal? The well-crafted impression is that of real people concealing true feelings, while groping toward some kind of reconciliation across unspoken barriers. Then Ward Bond and the posse arrive and slam-bang stereotypes take over. The promising beginning is lost, while Ford reverts to form by replacing character with caricature. Bond, for example, stands not just as a gruff old man, but as The Gruff Old Man; Jeffrey Hunter is not just a callow youth, but The Callow Youth; and most egregiously, Ken Curtis is not merely one more country yokel, but The Rub-your-Nose-In-It Country Yokel. Moreover, conversation ceases, hat-throwing and shouting take over, and genuine interaction gives way to exaggerated personalities doing little more than bouncing off one another. Even Wayne's one-note avenger comes close to parody, (unlike others, however, he is never mocked). Of course, such caricatures provide ample grist for Ford's broad idea of humor. Nonetheless, the comic set-ups come perilously close at times to a Three Stooges level, particularly the scenes with Old Mose, and with Bond and Patrick Wayne. I'm not against comic relief, but I am when it flirts with burlesque in an otherwise serious film.

More could be pointed out, such as the distracting subplots, or the ludicrous wedding sequence, or most glaringly, the climax with its sudden, unmotivated change of heart-- after all, it's the racial conflict that drives the plot. I guess what really bothers me is how blithely Ford substitutes his own highly simplistic vision of the Old West for any really plausible version. There's a basic lack of respect for the material, which allows, for example, such facile touches as Jorgensen's unweathered two-story wooden house in the middle of the desert, or Vera Miles' brocaded form-fitting wedding gown that appears to have been flown in from Paris. My point is not that the film lacks merit-- the justly celebrated doorway shots, for example. Rather, it's one of perspective-- this is an entertaining film but far from a masterpiece.The Searchers may be lauded and popular with many. Nonetheless, beneath the glossy surface lies an under-developed theme that really deserved better than standard stock company treatment. In short, Thomson is wrong. The Searchers is not an exception to Ford's usual product. Rather, it's just a little less compromised.

If there is only one western that you must see from John Ford, I would say it is this one; though THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALENCE is also absolutely unique, outstanding too. The element that makes those two films so stunning is not only the directing but the plot. This scheme was never made before and rarely copied since. Of course THE SEARCHERS plot will more or less inspire THE PROFESSIONALS, one decade later, from director Richard Brooks; just the overall scheme and especially ending, moral. The settings, landscape, music, acting, characters, everything is jawdropping and provokes emotion for anyone sensitive enough to feel all the power of this terrififc western. John Wayne gives his best performance, even better than in WAKE OF THE RED WITCH. One of the greatest ending ever.

The best western ever made is how many regard this 1956 John Ford classic. Its star John Wayne gave his most winning performance and it is reputed to have been his favourite movie even to the extent of his naming his last born son Ethan after the character he played. Ford's beloved Monument Valley in Arizona never looked more spectacular in Vista Vision and colour and over the years the picture has gained cult status. An integral part of the combined elements that makes THE SEARCHERS great is Max Steiner's outstanding score. It is the picture's driving force - its backbone. Steiner's music propels the film forward, unifies the narrative and gives greater density to its key scenes. In fact without his music much of the picture's impact would be considerably diminished. Yet I am consistently amazed and at a total loss to see here on these pages - where the best part of 400 reviews appear - that Steiner's music is hardly referred to at all by any of the writers. Not only that but even on the extras of the last DVD release three well established film directors, Martin Scorsese, John Milius and Peter Bogdanovitch each speak glowingly of Ford's masterpiece but fail to mention Steiner's exceptional contribution. Bogdanovitch, at one stage, briefly mentions the music and how good it is but never puts a name on its composer. I find this not only doctrinaire but quite bizarre that these three men, who you would imagine should know better, would have such a detached attitude concerning one of the most perfectly conceived scores for a motion picture. Therefore I will attempt here to amend this anomaly and the afore mentioned omissions and give some deserving credence to Max Steiner's exceptional music for THE SEARCHERS which has well earned its place in the history of cinema.

A veritable orchestral explosion opens the picture in the form of a fanfare over the Warner Bros. logo. As the credits roll we hear the haunting Stan Jones ballad "Song Of The Searchers" wonderfully rendered by Ford favourites The Sons Of the Pioneers. The composer later interpolates this song into his score as the theme for the racist protagonist Ethan Edwards (Wayne). Then a lovely version - scored for guitar, solo trumpet and strings - of the traditional ballad "Lorena" plays under Ford's evocative 'frame within a frame' opening scene as the door of a remote homestead opens to reveal an approaching rider. It then skillfully segues into "Bonnie Blue Flag" to point up the rider's confederate allegiance. The "Lorena" ballad later becomes the family theme and is especially effective on solo violin for the scene where Ethan gives the young Debbie his wartime medal as her "gold locket" ("Oh, let her have it - it doesn't amount to much" declares Ethan somberly). And later it is arrestingly heard on spinet as Ethan bids farewell to the family and rides out with the posse to begin what effectively will be his great search. But where the score really shines is in the powerful music for the Indian sequences. Here there is a palpable authenticity in the scoring. Aided by the clever orchestrations of Murrey Cutter and some virtuoso playing by the Warner Bros. orchestra (particularly in the percussion section) Steiner fires on all cylinders adding realism, pathos and a sense of foreboding. There are echoes of the composer's "King Kong" (1933) in the cue for the scene where the Indians surround the posse and the music becomes rhythmically savage for the charge at the river and for the attack on the Indian camp near the finale. The composer's celebrated "Indian Idyll" (which he originally wrote five years earlier for the Burt Lancaster picture "Jim Thorpe-All American") comes into play and can be heard to splendid effect in the Indian camp sequences and as the motif for Look, Martin's (Jeffrey Hunter) new Indian "wife". Hearing these cues one can't help but wonder how remarkable it is that this most romantic of film composers - steeped in the musical tradition of late 19th century Vienna - his birthplace - should be so ethnically proficient at musically depicting the native American. More akin to what we have come to expect from this composer are lovely cues such as the sprightly theme for Martin and the lush and sweeping music for Martin and Laurie (Vere Miles). The score - and the movie - ends just like it began with "The Song Of The Searchers" playing as Ethan and Martin finally bring Debbie home and conclusively the door of a homestead closes on Ethan where a brief fortissimo quotation from that explosive fanfare closes the picture.

Alongside the great film music works of Miklos Rozsa, Alfred Newman, Dimitri Tiomkin and others Max Steiner's music for THE SEARCHERS stands head high as one the finest scores ever written for one the finest films ever made and as such should, and must, be alluded to in any dissertation or essay on the film.

A veritable orchestral explosion opens the picture in the form of a fanfare over the Warner Bros. logo. As the credits roll we hear the haunting Stan Jones ballad "Song Of The Searchers" wonderfully rendered by Ford favourites The Sons Of the Pioneers. The composer later interpolates this song into his score as the theme for the racist protagonist Ethan Edwards (Wayne). Then a lovely version - scored for guitar, solo trumpet and strings - of the traditional ballad "Lorena" plays under Ford's evocative 'frame within a frame' opening scene as the door of a remote homestead opens to reveal an approaching rider. It then skillfully segues into "Bonnie Blue Flag" to point up the rider's confederate allegiance. The "Lorena" ballad later becomes the family theme and is especially effective on solo violin for the scene where Ethan gives the young Debbie his wartime medal as her "gold locket" ("Oh, let her have it - it doesn't amount to much" declares Ethan somberly). And later it is arrestingly heard on spinet as Ethan bids farewell to the family and rides out with the posse to begin what effectively will be his great search. But where the score really shines is in the powerful music for the Indian sequences. Here there is a palpable authenticity in the scoring. Aided by the clever orchestrations of Murrey Cutter and some virtuoso playing by the Warner Bros. orchestra (particularly in the percussion section) Steiner fires on all cylinders adding realism, pathos and a sense of foreboding. There are echoes of the composer's "King Kong" (1933) in the cue for the scene where the Indians surround the posse and the music becomes rhythmically savage for the charge at the river and for the attack on the Indian camp near the finale. The composer's celebrated "Indian Idyll" (which he originally wrote five years earlier for the Burt Lancaster picture "Jim Thorpe-All American") comes into play and can be heard to splendid effect in the Indian camp sequences and as the motif for Look, Martin's (Jeffrey Hunter) new Indian "wife". Hearing these cues one can't help but wonder how remarkable it is that this most romantic of film composers - steeped in the musical tradition of late 19th century Vienna - his birthplace - should be so ethnically proficient at musically depicting the native American. More akin to what we have come to expect from this composer are lovely cues such as the sprightly theme for Martin and the lush and sweeping music for Martin and Laurie (Vere Miles). The score - and the movie - ends just like it began with "The Song Of The Searchers" playing as Ethan and Martin finally bring Debbie home and conclusively the door of a homestead closes on Ethan where a brief fortissimo quotation from that explosive fanfare closes the picture.

Alongside the great film music works of Miklos Rozsa, Alfred Newman, Dimitri Tiomkin and others Max Steiner's music for THE SEARCHERS stands head high as one the finest scores ever written for one the finest films ever made and as such should, and must, be alluded to in any dissertation or essay on the film.

Many people would probably watch a film like this and come away thinking that it was too long and slow - but they'd be wrong. It's the perfect length for an epic visual feast. It tells a story in it's own impeccable time. It is a story spread over a period of years after all. The dialogue is brilliant, I love the way (now considered cheesy or clichéd phrases etc) the characters express themselves. The concept of the ruthless, merciless good guy isn't new but in this film I feel it's produced to perfection. I can only imagine that this movie is one of the first of it's kind.

In an attempt not to be over analysing things, it seems to me that there is real depth to an old school cowboy and Indian picture. This is regard to the themes of racism and revenge, the war torn vet. Even the more obvious rebellion and admiration adds even more complexity to it. However, by modern standards, the acting is questionable. It's melodramatic to say the least and John Wayne, as iconic as he is, isn't brilliant. You can see him anticipating his next lines, you can see in his eyes that this is just another day at the office. But hell, this was a different time and a different method.

In an attempt not to be over analysing things, it seems to me that there is real depth to an old school cowboy and Indian picture. This is regard to the themes of racism and revenge, the war torn vet. Even the more obvious rebellion and admiration adds even more complexity to it. However, by modern standards, the acting is questionable. It's melodramatic to say the least and John Wayne, as iconic as he is, isn't brilliant. You can see him anticipating his next lines, you can see in his eyes that this is just another day at the office. But hell, this was a different time and a different method.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesBeulah Archuletta (Look) was found crying in one of the tipis by John Wayne in between shooting scenes. When Wayne asked her why she was crying, she responded that she was going to miss her son's wedding because she was filming her scenes at the time. Wayne stopped production of the film for a few days and flew her to California so that she could attend the wedding.

- GaffesThe "dead" Indian under the rock, when the rock is removed, is clearly breathing.

- Générique farfeluThe credits state this Warner Brothers film is in VistaVision; this may be the only Warner film in VistaVision.

- ConnexionsEdited into Histoire(s) du cinéma: Fatale beauté (1994)

- Bandes originalesThe Searchers (Main Theme)

Composed by Max Steiner

Lyrics by Stan Jones

Sung by Sons of the Pioneers (uncredited)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et surveiller les recommandations personnalisées

Détails

Box-office

- Budget

- 3 750 000 $ US (estimation)

- Brut – à l'échelle mondiale

- 1 071 $ US

- Durée1 heure 59 minutes

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was La prisonnière du désert (1956) officially released in India in Hindi?

Répondre