Un vétéran de la guerre civile américaine se lance dans une expédition visant à délivrer sa nièce des Comanches.Un vétéran de la guerre civile américaine se lance dans une expédition visant à délivrer sa nièce des Comanches.Un vétéran de la guerre civile américaine se lance dans une expédition visant à délivrer sa nièce des Comanches.

- Prix

- 4 victoires et 4 nominations au total

Patrick Wayne

- Lt. Greenhill

- (as Pat Wayne)

Avis en vedette

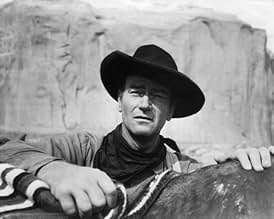

If there is only one western that you must see from John Ford, I would say it is this one; though THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALENCE is also absolutely unique, outstanding too. The element that makes those two films so stunning is not only the directing but the plot. This scheme was never made before and rarely copied since. Of course THE SEARCHERS plot will more or less inspire THE PROFESSIONALS, one decade later, from director Richard Brooks; just the overall scheme and especially ending, moral. The settings, landscape, music, acting, characters, everything is jawdropping and provokes emotion for anyone sensitive enough to feel all the power of this terrififc western. John Wayne gives his best performance, even better than in WAKE OF THE RED WITCH. One of the greatest ending ever.

Even if you've never seen John Ford's THE SEARCHERS, you will have, undoubtedly, seen a film that owes it's 'style' to the film. DANCES WITH WOLVES, THE OUTLAW JOSIE WALES, UNFORGIVEN, JEREMIAH JOHNSON, and OPEN RANGE are just a few westerns that have 'borrowed' from it, but THE SEARCHERS' impact transcends the genre, itself; STAR WARS, THE English PATIENT, THE LAST SAMURAI, even THE LORD OF THE RINGS have elements that can be traced back to Ford's 1956 'intimate' epic. When you add the fact that THE SEARCHERS also contains John Wayne's greatest performance to the film's merits, it becomes easy to see why it is on the short list of the greatest motion pictures ever made.

The plot is deceptively simple; after a Comanche raiding party massacres a family, taking the youngest daughter prisoner, her uncle, Ethan Edwards (Wayne), and adopted brother, Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), begin a long quest to try and rescue her. Over the course of years, a rich tapestry of characters and events unfold, as the nature of the pair's motives are revealed, and bigoted, bitter Edwards emerges as a twisted man bent on killing the 'tainted' white girl. Only Pawley's love of his 'sister' and determination to protect her stands in his way, making the film's climax, and Wayne's portrayal of Edwards, an unforgettable experience.

With all of Ford's unique 'touches' clearly in evidence (the doorways 'framing' the film's opening and conclusion, with a cave opening serving the same function at the film's climax; the extensive use of Monument Valley; and the nearly lurid palette of color highlighting key moments) and his reliance on his 'stock' company of players (Wayne, Ward Bond, John Qualen, Olive Carey, Harry Carey, Jr, Hank Worden, and Ken Curtis), the film marks the emergence of the 'mature' Ford, no longer deifying the innocence of the era, but dealing with it in human terms, where 'white men' were as capable of savagery as Indians, frequently with less justification.

Featuring 18-year old Natalie Wood in one of her first 'adult' roles, the sparkling Vera Miles as Pawley's love interest, Wayne's son Patrick in comic relief, and the harmonies of the Sons of the Pioneers accenting Max Steiner's rich score, THE SEARCHERS is a timeless movie experience that becomes richer with each viewing.

It is truly a masterpiece!

The plot is deceptively simple; after a Comanche raiding party massacres a family, taking the youngest daughter prisoner, her uncle, Ethan Edwards (Wayne), and adopted brother, Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), begin a long quest to try and rescue her. Over the course of years, a rich tapestry of characters and events unfold, as the nature of the pair's motives are revealed, and bigoted, bitter Edwards emerges as a twisted man bent on killing the 'tainted' white girl. Only Pawley's love of his 'sister' and determination to protect her stands in his way, making the film's climax, and Wayne's portrayal of Edwards, an unforgettable experience.

With all of Ford's unique 'touches' clearly in evidence (the doorways 'framing' the film's opening and conclusion, with a cave opening serving the same function at the film's climax; the extensive use of Monument Valley; and the nearly lurid palette of color highlighting key moments) and his reliance on his 'stock' company of players (Wayne, Ward Bond, John Qualen, Olive Carey, Harry Carey, Jr, Hank Worden, and Ken Curtis), the film marks the emergence of the 'mature' Ford, no longer deifying the innocence of the era, but dealing with it in human terms, where 'white men' were as capable of savagery as Indians, frequently with less justification.

Featuring 18-year old Natalie Wood in one of her first 'adult' roles, the sparkling Vera Miles as Pawley's love interest, Wayne's son Patrick in comic relief, and the harmonies of the Sons of the Pioneers accenting Max Steiner's rich score, THE SEARCHERS is a timeless movie experience that becomes richer with each viewing.

It is truly a masterpiece!

A John Ford masterwork that's rich and spacious, just like the gorgeous western countryside that splashes every backdrop. John Wayne plays a flawed centerpiece, a grizzled former soldier with a chip on his shoulder and a strange, conflicted relationship with his extended family. As usual, cool confidence and raw masculinity seep from his pores and he takes hold of each scene with a pair of strong, old cowherder's hands. This is a film that rewards an active imagination, as there's much going on between the lines that, without being spelled out, brands the cast with an unusual level of depth and detail. Unspoken histories flesh out most every character, allowing even generic walk-ons to mosey into the picture at most any moment and cast ripples throughout the entire tapestry. It can be slow at times, and the casting of a very obviously non-native actor to lead the stereotypical enemy Comanche tribe doesn't sit well, but both such faults can be generally chalked up to the dated eccentricities of that era. Take the time to soak it all in, to look deeper than the superficial story, and you'll find a wealth of spoils.

A lone home amidst tranquil mesas. A family gathers on their front porch to watch a solitary man ride slowly up to their ranch on his horse in the waning sun. He stops, disembarks and walks up to the house, all in one single weary move. Note his stance, the rugged tiredness of life etched on his face. This lone drifter is Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) and is perhaps the most brilliant character devised by Wayne and director John Ford. As the film progresses, we learn of his military days, his contempt of Indians and, most importantly, his psyche. Compared to another John ford movie, "Stagecoach", we can see the massive differences in character psychology and within the genre itself. Gone are the days of the brave hero riding in to save the day with wistful smiles all around; instead we have a savage man on an odyssey of revenge, hatred and bloodshed.

In one scene, Ethan and a search party comes across a dead Indian buried in the ground. Ethan's suppressed rage overcomes him, and he shoots the corpse's eyes out. "What good did that do ya?" asks the Reverend. Ethan coolly replies, "Ain't got no eyes so he can't enter the spirit land, has to wander forever between the winds". This is by far my favourite line in the movie, because of the resonance it has at the end, with Ethan walking away into the winds, doomed to forever drift the earth. This movie is a beautiful spectacle of sight and sound. Not only do we marvel at scenes in Ford's beloved Monument Valley, we also find ourselves amazed at the level of detail in set design. Each frame is as if it were from a painter's canvas. Colour coordination was certainly something John Ford and his cinematographers fit perfectly into. There are few vibrant colours in each frame, but those that exist pop out vividly amongst the bleak, sepia-stained walls of the houses, and the valley.

John Ford again demonstrates his powerful storytelling technique by using several methods of progressing the narrative. While crosscutting between action is used sparingly, a quasi-flashback stemming from a letter of Luke's kept my attention firmly rooted to my screen. These different methods of narrative progression are important because it keeps the viewer continuously involved with the story. Not once did I feel as if a particular scene droned on and on for too long, instead I felt captivated not only by a gripping storyline, but also because of the brilliant dichotomy between Ethan Edwards and the other characters. The Searchers is a lesson on psychology, sociology and filmmaking all at once. I love it.

In one scene, Ethan and a search party comes across a dead Indian buried in the ground. Ethan's suppressed rage overcomes him, and he shoots the corpse's eyes out. "What good did that do ya?" asks the Reverend. Ethan coolly replies, "Ain't got no eyes so he can't enter the spirit land, has to wander forever between the winds". This is by far my favourite line in the movie, because of the resonance it has at the end, with Ethan walking away into the winds, doomed to forever drift the earth. This movie is a beautiful spectacle of sight and sound. Not only do we marvel at scenes in Ford's beloved Monument Valley, we also find ourselves amazed at the level of detail in set design. Each frame is as if it were from a painter's canvas. Colour coordination was certainly something John Ford and his cinematographers fit perfectly into. There are few vibrant colours in each frame, but those that exist pop out vividly amongst the bleak, sepia-stained walls of the houses, and the valley.

John Ford again demonstrates his powerful storytelling technique by using several methods of progressing the narrative. While crosscutting between action is used sparingly, a quasi-flashback stemming from a letter of Luke's kept my attention firmly rooted to my screen. These different methods of narrative progression are important because it keeps the viewer continuously involved with the story. Not once did I feel as if a particular scene droned on and on for too long, instead I felt captivated not only by a gripping storyline, but also because of the brilliant dichotomy between Ethan Edwards and the other characters. The Searchers is a lesson on psychology, sociology and filmmaking all at once. I love it.

A second look at this film is long overdue. It's been hailed by many as a masterpiece. Even the anti-Ford critic David Thomson in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film classifies it as an exceptional work. I don't know whether it's the Ford mystique, the Wayne icon, or the mesmerizing beauty of Monument Valley that holds this movie to a different standard from most Westerns. But something is at work that numbs a critical eye-level inquiry. The Searchers is a good film, but no masterpiece, and certainly does not belong in the American Film Institute's list of top 100 films of all time. A brief look at some of the more obvious defects:

Ford makes picture postcards out of the soaring spires and buttes. At no point, however, does he come to grips with the real harshness of the terrain. This is desert country. Hardly anything grows-- just look at the sparseness of greenery. Yet we're told cattle herds feed here in large enough numbers to support families, (In the movie, Jorgensen's right-- they would be better off raising pigs than cattle). Then too, there is absolutely no hint of the desert heat or cold affecting anything or anybody. The parties go here and there with slim regard for what the conditions actually afford. In short, the celebrated landscape amounts to little more than a majestic backdrop without a true reality of its own. Ford may love this Spartan terrain, but he gives it scant respect.

Similarly, the film-maker undercuts the naturalism of the vaunted visuals. The audience gets an awesome flow of natural wonders, only to have the flow interrupted by outdoor sets so painfully obvious, they can't be ignored, (consider the Futterman ambush scene, for one). As a result, visual continuity is sacrificed and so is fidelity to the intended atmosphere. Suddenly we're jolted out of the scenic spell back into recognition that this is, after all, only a movie. Where, one wonders, was Ford's very real poetic eye in these disruptive scenes, and why didn't he insist on shooting all outdoor scenes outdoors-- especially after traveling to Colorado for the great snow scenes. As a premier film-maker, I'm sure he had the clout. Nonetheless, the lapse is another glaring defect.

There's another problem with respect, this time for the adversary. In fact, the Indians do get some concessions--Scar is provided a moment of motivation and a good sarcastic aside-- but not much else. As in Ford's cavalry cycle, aboriginal peoples still exist as convenient devices and sitting ducks. From the film's several battles, it seems the Indians know nothing about combat tactics. Stupidly, they never attack unless an escape route is left open to the fleeing settlers. And when they attack frontally across the river or in front of the cave, they mass in a bunch so the dug-in whites can hardly miss. No wonder there are so few Indians left. In most Westerns, this cliché would not even merit comment, but remember this one's supposed to be a "masterpiece".(For a gauge of Ford's dishonesty, compare his cardboard warriors with the skilled and savvy combatants in the similarly themed "Ulzana's Raid" {1973}).

For what is required of the actors, contrast the first ten minutes with the movie's remainder. Those first few minutes are little short of superb. There's a low-key naturalism and subtlety that's fascinating-- Just who is Ethan Edwards? What is the tension between his brother and him? And where did he get that impressive war medal? The well-crafted impression is that of real people concealing true feelings, while groping toward some kind of reconciliation across unspoken barriers. Then Ward Bond and the posse arrive and slam-bang stereotypes take over. The promising beginning is lost, while Ford reverts to form by replacing character with caricature. Bond, for example, stands not just as a gruff old man, but as The Gruff Old Man; Jeffrey Hunter is not just a callow youth, but The Callow Youth; and most egregiously, Ken Curtis is not merely one more country yokel, but The Rub-your-Nose-In-It Country Yokel. Moreover, conversation ceases, hat-throwing and shouting take over, and genuine interaction gives way to exaggerated personalities doing little more than bouncing off one another. Even Wayne's one-note avenger comes close to parody, (unlike others, however, he is never mocked). Of course, such caricatures provide ample grist for Ford's broad idea of humor. Nonetheless, the comic set-ups come perilously close at times to a Three Stooges level, particularly the scenes with Old Mose, and with Bond and Patrick Wayne. I'm not against comic relief, but I am when it flirts with burlesque in an otherwise serious film.

More could be pointed out, such as the distracting subplots, or the ludicrous wedding sequence, or most glaringly, the climax with its sudden, unmotivated change of heart-- after all, it's the racial conflict that drives the plot. I guess what really bothers me is how blithely Ford substitutes his own highly simplistic vision of the Old West for any really plausible version. There's a basic lack of respect for the material, which allows, for example, such facile touches as Jorgensen's unweathered two-story wooden house in the middle of the desert, or Vera Miles' brocaded form-fitting wedding gown that appears to have been flown in from Paris. My point is not that the film lacks merit-- the justly celebrated doorway shots, for example. Rather, it's one of perspective-- this is an entertaining film but far from a masterpiece.The Searchers may be lauded and popular with many. Nonetheless, beneath the glossy surface lies an under-developed theme that really deserved better than standard stock company treatment. In short, Thomson is wrong. The Searchers is not an exception to Ford's usual product. Rather, it's just a little less compromised.

Ford makes picture postcards out of the soaring spires and buttes. At no point, however, does he come to grips with the real harshness of the terrain. This is desert country. Hardly anything grows-- just look at the sparseness of greenery. Yet we're told cattle herds feed here in large enough numbers to support families, (In the movie, Jorgensen's right-- they would be better off raising pigs than cattle). Then too, there is absolutely no hint of the desert heat or cold affecting anything or anybody. The parties go here and there with slim regard for what the conditions actually afford. In short, the celebrated landscape amounts to little more than a majestic backdrop without a true reality of its own. Ford may love this Spartan terrain, but he gives it scant respect.

Similarly, the film-maker undercuts the naturalism of the vaunted visuals. The audience gets an awesome flow of natural wonders, only to have the flow interrupted by outdoor sets so painfully obvious, they can't be ignored, (consider the Futterman ambush scene, for one). As a result, visual continuity is sacrificed and so is fidelity to the intended atmosphere. Suddenly we're jolted out of the scenic spell back into recognition that this is, after all, only a movie. Where, one wonders, was Ford's very real poetic eye in these disruptive scenes, and why didn't he insist on shooting all outdoor scenes outdoors-- especially after traveling to Colorado for the great snow scenes. As a premier film-maker, I'm sure he had the clout. Nonetheless, the lapse is another glaring defect.

There's another problem with respect, this time for the adversary. In fact, the Indians do get some concessions--Scar is provided a moment of motivation and a good sarcastic aside-- but not much else. As in Ford's cavalry cycle, aboriginal peoples still exist as convenient devices and sitting ducks. From the film's several battles, it seems the Indians know nothing about combat tactics. Stupidly, they never attack unless an escape route is left open to the fleeing settlers. And when they attack frontally across the river or in front of the cave, they mass in a bunch so the dug-in whites can hardly miss. No wonder there are so few Indians left. In most Westerns, this cliché would not even merit comment, but remember this one's supposed to be a "masterpiece".(For a gauge of Ford's dishonesty, compare his cardboard warriors with the skilled and savvy combatants in the similarly themed "Ulzana's Raid" {1973}).

For what is required of the actors, contrast the first ten minutes with the movie's remainder. Those first few minutes are little short of superb. There's a low-key naturalism and subtlety that's fascinating-- Just who is Ethan Edwards? What is the tension between his brother and him? And where did he get that impressive war medal? The well-crafted impression is that of real people concealing true feelings, while groping toward some kind of reconciliation across unspoken barriers. Then Ward Bond and the posse arrive and slam-bang stereotypes take over. The promising beginning is lost, while Ford reverts to form by replacing character with caricature. Bond, for example, stands not just as a gruff old man, but as The Gruff Old Man; Jeffrey Hunter is not just a callow youth, but The Callow Youth; and most egregiously, Ken Curtis is not merely one more country yokel, but The Rub-your-Nose-In-It Country Yokel. Moreover, conversation ceases, hat-throwing and shouting take over, and genuine interaction gives way to exaggerated personalities doing little more than bouncing off one another. Even Wayne's one-note avenger comes close to parody, (unlike others, however, he is never mocked). Of course, such caricatures provide ample grist for Ford's broad idea of humor. Nonetheless, the comic set-ups come perilously close at times to a Three Stooges level, particularly the scenes with Old Mose, and with Bond and Patrick Wayne. I'm not against comic relief, but I am when it flirts with burlesque in an otherwise serious film.

More could be pointed out, such as the distracting subplots, or the ludicrous wedding sequence, or most glaringly, the climax with its sudden, unmotivated change of heart-- after all, it's the racial conflict that drives the plot. I guess what really bothers me is how blithely Ford substitutes his own highly simplistic vision of the Old West for any really plausible version. There's a basic lack of respect for the material, which allows, for example, such facile touches as Jorgensen's unweathered two-story wooden house in the middle of the desert, or Vera Miles' brocaded form-fitting wedding gown that appears to have been flown in from Paris. My point is not that the film lacks merit-- the justly celebrated doorway shots, for example. Rather, it's one of perspective-- this is an entertaining film but far from a masterpiece.The Searchers may be lauded and popular with many. Nonetheless, beneath the glossy surface lies an under-developed theme that really deserved better than standard stock company treatment. In short, Thomson is wrong. The Searchers is not an exception to Ford's usual product. Rather, it's just a little less compromised.

Le saviez-vous

- AnecdotesBeulah Archuletta (Look) was found crying in one of the tipis by John Wayne in between shooting scenes. When Wayne asked her why she was crying, she responded that she was going to miss her son's wedding because she was filming her scenes at the time. Wayne stopped production of the film for a few days and flew her to California so that she could attend the wedding.

- GaffesThe "dead" Indian under the rock, when the rock is removed, is clearly breathing.

- Générique farfeluThe credits state this Warner Brothers film is in VistaVision; this may be the only Warner film in VistaVision.

- ConnexionsEdited into Histoire(s) du cinéma: Fatale beauté (1994)

- Bandes originalesThe Searchers (Main Theme)

Composed by Max Steiner

Lyrics by Stan Jones

Sung by Sons of the Pioneers (uncredited)

Meilleurs choix

Connectez-vous pour évaluer et surveiller les recommandations personnalisées

Détails

Box-office

- Budget

- 3 750 000 $ US (estimation)

- Brut – à l'échelle mondiale

- 1 071 $ US

- Durée1 heure 59 minutes

Contribuer à cette page

Suggérer une modification ou ajouter du contenu manquant

Lacune principale

By what name was La prisonnière du désert (1956) officially released in India in Hindi?

Répondre