PUNTUACIÓN EN IMDb

7,7/10

20 mil

TU PUNTUACIÓN

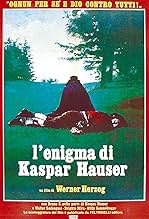

Un joven llamado Kaspar Hauser aparece repentinamente en Nuremberg en 1828, apenas puede hablar o caminar. Él tiene una nota extraña.Un joven llamado Kaspar Hauser aparece repentinamente en Nuremberg en 1828, apenas puede hablar o caminar. Él tiene una nota extraña.Un joven llamado Kaspar Hauser aparece repentinamente en Nuremberg en 1828, apenas puede hablar o caminar. Él tiene una nota extraña.

- Dirección

- Guión

- Reparto principal

- Premios

- 5 premios y 3 nominaciones en total

Reseñas destacadas

A truely visionary work!!I have always been fascinated with the story that this film tells.Herzog seems to be an expert at showing the way that an outsider relates to the world.Bruno S. is amazing in the lead role , Herzog has definitely made the right casting choice.the movie is just a must for all fans of cinema,even if your not a Herzog fanatic you will still be moved by this extraordinary vision!!!

Even if this film had failed on the level of character or narrative (which it doesn't), I would still love this movie for its incredible imagery. The memory/dream sequences are haunting and will never leave my head. The opening shot of a field, long blades grass bowing under the wind to the music of Pachelbel, is extraordinary. And of course there's the performance of Bruno S, the most intensely hypnotic and genuine performance you will ever see.

But my favorite scene is of the impresario and the dwarf king and his kingdom. This is a true Herzog moment -- bizarre but somehow still a moment of striking epiphany -- the dwarf a parallel, isolated soul to Kasper's own isolated, lonely soul. The extremity and weirdness of moments like these seem commonplace and everyday in a Herzog film, and therefore somehow commonplace and everyday even in our own lives.

But my favorite scene is of the impresario and the dwarf king and his kingdom. This is a true Herzog moment -- bizarre but somehow still a moment of striking epiphany -- the dwarf a parallel, isolated soul to Kasper's own isolated, lonely soul. The extremity and weirdness of moments like these seem commonplace and everyday in a Herzog film, and therefore somehow commonplace and everyday even in our own lives.

One of the most evocative and quietly moving films ever produced on the subjects of cultural displacement, exploitation and personal despair, with director Werner Herzog producing a pure work of cinema as sensitive as the character that he depicts. With this particular film, Herzog created perhaps the ultimate statement about the perseverance of the human spirit, whilst simultaneously creating a world that is deliberately abstracted in order to convey the perspective of a character out of step with society and the period that embraced him. Like many of Herzog's films from this era, such as Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970) and Stroszek (1977) in particular, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1975) is essentially about looking at the world from the outside in; with all of the separate elements distorted in order to convey the world-view of this perennial outsider seeing himself for the very first time. In a manner similar to that of David Lynch's subsequent film, The Elephant Man (1980), Herzog uses elements of the real-life story behind the character simply as an excuse to ruminate on the notions of alienation, the nature of conspiracy, personal exploitation and degradation, as well as the often underhanded mechanisms of a seemingly enlightened society, in a way that goes beyond the mere superficial levels of the narrative.

The point of the film is expressed by the original German title, "Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle", or "every man for himself and God against all". In keeping with this, the nature of religion is brought up twice in the film and dismissed on both occasions by the central character, who claims to be too unfamiliar with the concept of spirituality to be able to make an informed opinion. The church argues that Kaspar should believe simply as an act of blind faith and that a leap of faith will overcome any such notions of knowledge or conception. It is a keen comment on the part of Herzog and one that ties into the idea of Kaspar as an unspoiled being; an almost childlike figure, though in the possession of a keen intelligence and a passionate creative spirit, who ultimately finds himself persecuted for reasons that neither he nor we could ever truly comprehend. In the hands of any other filmmaker, the depiction of Kaspar would have no doubt been that of the traditional outcast; desperately trying to find their own identity in the form of a triumph over adversity. However - again looking back to the subject matter of Even Dwarfs Started Small - Herzog instead gives us a representation of the sane man in the insane world; showing us how the corruption and inherent evil of self-preservation can take a gentle and contemplative spirit and crush it completely; a notion that is beautifully illustrated in a cinematic sense by the scene in which Kaspar sows his name with seeds into the flower bed, only to return one day from an outing to find that it has been trampled by an intruder.

Moments like these are characteristic of Herzog's continually fascinating style of direction from this particular period, as he approached cinema from a perspective similar to that of filmmakers like Peter Watkins, Ken Russell or Pier Paolo Pasolini by investigating the workings of a period setting from a more contemporary perspective. So, we have the authentic costumes, locations and an attempt to recreate the values and mannerisms of this particular society, all the while being abstracted by Herzog's continually probing camera that lingers and explores - often hand-held - through the various cobbled back-streets and stately homes from where the drama plays out. Herzog has often claimed that there is (or was) no real distinction between his documentary work and his more cinematic features, with both particular examples coming from the same place and attempting to convey what Herzog refers to as "the ecstatic truth". You can see this ideology clearly with the film, as the director mixes a non-actor in the shape of Bruno S. alongside professional performers like Walter Ladengast and Brigitte Mira. As a result of this, there is a heightened quality to the portrayal of Kaspar, as well as a genuine sense of dependence on the two characters that come to care for him, as the more experienced cast members take Bruno under their wing and coach him along in a manner reminiscent of the actual characters themselves.

The juxtaposition between the two styles of documentary realism and purposeful cinematic expression can be seen in the visualisation of the film; from the naturalistic cinematography of Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein - with its emphasis on light and shadow and expressive use of landscapes - to the use of classical music (which here gives the film a yearning, almost romantic sense of melodrama to contrast against the more downbeat elements of the film). From its stark and impressionistic opening vignette - with its allusions to a dreamlike evocation somewhat removed from the rest of the film - to the beguiling fever-dream of caravans moving through a barren desert as the film reaches its close, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is an absolute masterpiece from a director here at the very top of his creative peak. It is without question unlike any other film you will ever see; one that is rich in character and a believable evocation of period detail, but one that also presents a genuinely unique and unforgettable cinematic vision. In Herzog's film, it is the world that is wrong and confused, with Kaspar becoming a sort of representation for the very greatest qualities of humanity in the face of this vile corruption. A powerful and emotive concept as passionately realised as the film itself.

The point of the film is expressed by the original German title, "Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle", or "every man for himself and God against all". In keeping with this, the nature of religion is brought up twice in the film and dismissed on both occasions by the central character, who claims to be too unfamiliar with the concept of spirituality to be able to make an informed opinion. The church argues that Kaspar should believe simply as an act of blind faith and that a leap of faith will overcome any such notions of knowledge or conception. It is a keen comment on the part of Herzog and one that ties into the idea of Kaspar as an unspoiled being; an almost childlike figure, though in the possession of a keen intelligence and a passionate creative spirit, who ultimately finds himself persecuted for reasons that neither he nor we could ever truly comprehend. In the hands of any other filmmaker, the depiction of Kaspar would have no doubt been that of the traditional outcast; desperately trying to find their own identity in the form of a triumph over adversity. However - again looking back to the subject matter of Even Dwarfs Started Small - Herzog instead gives us a representation of the sane man in the insane world; showing us how the corruption and inherent evil of self-preservation can take a gentle and contemplative spirit and crush it completely; a notion that is beautifully illustrated in a cinematic sense by the scene in which Kaspar sows his name with seeds into the flower bed, only to return one day from an outing to find that it has been trampled by an intruder.

Moments like these are characteristic of Herzog's continually fascinating style of direction from this particular period, as he approached cinema from a perspective similar to that of filmmakers like Peter Watkins, Ken Russell or Pier Paolo Pasolini by investigating the workings of a period setting from a more contemporary perspective. So, we have the authentic costumes, locations and an attempt to recreate the values and mannerisms of this particular society, all the while being abstracted by Herzog's continually probing camera that lingers and explores - often hand-held - through the various cobbled back-streets and stately homes from where the drama plays out. Herzog has often claimed that there is (or was) no real distinction between his documentary work and his more cinematic features, with both particular examples coming from the same place and attempting to convey what Herzog refers to as "the ecstatic truth". You can see this ideology clearly with the film, as the director mixes a non-actor in the shape of Bruno S. alongside professional performers like Walter Ladengast and Brigitte Mira. As a result of this, there is a heightened quality to the portrayal of Kaspar, as well as a genuine sense of dependence on the two characters that come to care for him, as the more experienced cast members take Bruno under their wing and coach him along in a manner reminiscent of the actual characters themselves.

The juxtaposition between the two styles of documentary realism and purposeful cinematic expression can be seen in the visualisation of the film; from the naturalistic cinematography of Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein - with its emphasis on light and shadow and expressive use of landscapes - to the use of classical music (which here gives the film a yearning, almost romantic sense of melodrama to contrast against the more downbeat elements of the film). From its stark and impressionistic opening vignette - with its allusions to a dreamlike evocation somewhat removed from the rest of the film - to the beguiling fever-dream of caravans moving through a barren desert as the film reaches its close, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is an absolute masterpiece from a director here at the very top of his creative peak. It is without question unlike any other film you will ever see; one that is rich in character and a believable evocation of period detail, but one that also presents a genuinely unique and unforgettable cinematic vision. In Herzog's film, it is the world that is wrong and confused, with Kaspar becoming a sort of representation for the very greatest qualities of humanity in the face of this vile corruption. A powerful and emotive concept as passionately realised as the film itself.

Werner Herzog's strange and enticing film divulges only what is known of the account of Kaspar Hauser, played by Bruno S., who dwelled for the first 17 years of his life shackled in a small basement room with nothing more than a toy horse to occupy him, without all contact with humans or other living things save for a stranger who gives food to him. One day in 1828, the same anonymous figure takes Kaspar out of his chamber, schools him on a handful of expressions and how to walk, and then leaves him standing still in a cobblestone court in Nuremberg. Kaspar is the focus of novelty and interest and is even put on display in a circus before being saved by an aristocrat who slowly and good-naturedly endeavors to renovate him. Kaspar gradually learns to read and write and forms unorthodox perspectives on religion and logic, but music is what gives him great pleasure. He draws the attention of members of the clergy, professors, and aristocracy.

The most telling scene is in fact my favorite, when Kaspar is being schooled by a psychologist who asks him a classic brain-buster, to which Kaspar gives an effortless, unusual, perfectly legitimate answer that is swiftly rejected by the psychologist for not being the standard answer. The people surrounding Kaspar in Herzog's film are perfectly subjugated, as in the scene where a little girl tries to teach Kaspar a nursery rhyme, and while it's clear that he doesn't know the meaning at all of the rhyme like she does and that he hasn't even developed as far as a small child, it's also clear that the small child has not developed far enough to know how to educate someone with less common knowledge than her.

Herzog chronicles the real-life mystery of Kaspar Hauser not so much as a creepy mystery but as a character study that demonstrates that society's traditional manner of perceiving the world may not essentially be the most well-founded or defensible, hence the film's brilliant original title, Every Man For Himself and God Against All, as all but laid bare when Kaspar's assertion that apples are tired is apparently substantiated by the incapability of his aristocratic savior to show support of the argument that they are lifeless objects subject to human control.

Bruno S. is Herzog's beautiful achievement. Bruno S., the disdained son of a prostitute, was beaten so cruelly by his mother as a toddler that he fell deaf for awhile. This caused him to be institutionalized for the next 23 years in countless institutes, regularly committing petty crimes. Regardless of this horrendous history, he became an autodidactic painter and musician. At the same time as these were his beloved pursuits, he was also pressed to take jobs in factories. Herzog saw him in a 1970 documentary, he swore to work with him. In and of himself, Bruno S. attested to the power of Herzog's vision. He was exceptionally strenuous to work with, at times not so much wanting but requiring numerous hours of screaming a scene could be shot. Owing to all of this, Bruno S. literally is a Kaspar Hauser, an inordinately tortured soul utilized for the sake of revealing the shock value of reality's hidden ugliness to common society. Kaspar is taken under the wing of several groups of people but whether their intentions are good or bad, he can never seem to live a life without the exploitation of his completely removed mind for the commotion of nobility or business.

Short of an accepted narrative or dramatic construction and full of indistinct imagery generated only by Herzog's instinct, many unexplained elements never resolve themselves in Herzog's unique character study, and they shouldn't. His encapsulating only what the world knows of this very little-known story intensifies the intrigue of it. Why did this strange person do this to Kaspar Hauser? Who was he?

The most telling scene is in fact my favorite, when Kaspar is being schooled by a psychologist who asks him a classic brain-buster, to which Kaspar gives an effortless, unusual, perfectly legitimate answer that is swiftly rejected by the psychologist for not being the standard answer. The people surrounding Kaspar in Herzog's film are perfectly subjugated, as in the scene where a little girl tries to teach Kaspar a nursery rhyme, and while it's clear that he doesn't know the meaning at all of the rhyme like she does and that he hasn't even developed as far as a small child, it's also clear that the small child has not developed far enough to know how to educate someone with less common knowledge than her.

Herzog chronicles the real-life mystery of Kaspar Hauser not so much as a creepy mystery but as a character study that demonstrates that society's traditional manner of perceiving the world may not essentially be the most well-founded or defensible, hence the film's brilliant original title, Every Man For Himself and God Against All, as all but laid bare when Kaspar's assertion that apples are tired is apparently substantiated by the incapability of his aristocratic savior to show support of the argument that they are lifeless objects subject to human control.

Bruno S. is Herzog's beautiful achievement. Bruno S., the disdained son of a prostitute, was beaten so cruelly by his mother as a toddler that he fell deaf for awhile. This caused him to be institutionalized for the next 23 years in countless institutes, regularly committing petty crimes. Regardless of this horrendous history, he became an autodidactic painter and musician. At the same time as these were his beloved pursuits, he was also pressed to take jobs in factories. Herzog saw him in a 1970 documentary, he swore to work with him. In and of himself, Bruno S. attested to the power of Herzog's vision. He was exceptionally strenuous to work with, at times not so much wanting but requiring numerous hours of screaming a scene could be shot. Owing to all of this, Bruno S. literally is a Kaspar Hauser, an inordinately tortured soul utilized for the sake of revealing the shock value of reality's hidden ugliness to common society. Kaspar is taken under the wing of several groups of people but whether their intentions are good or bad, he can never seem to live a life without the exploitation of his completely removed mind for the commotion of nobility or business.

Short of an accepted narrative or dramatic construction and full of indistinct imagery generated only by Herzog's instinct, many unexplained elements never resolve themselves in Herzog's unique character study, and they shouldn't. His encapsulating only what the world knows of this very little-known story intensifies the intrigue of it. Why did this strange person do this to Kaspar Hauser? Who was he?

"This is the story of a soul", someone said and I agree because loneliness is here described through a slow moving plot and endless silences which make us see Kaspar Hauser not as a man but as something more sulfuric, almost a being from outer space. The performance of Bruno S. is simply moving and caused me a lot of tears and the use of time through the narration is perfect for a film of this kind. The poetic vision of Werner Herzog is very peculiar and unique and you can love it or hate it but you cannot ignore it. Herzog doesn't care about the audience, he tells what it wants in the way he likes and that's the praise and the defect of European cinema and it's what makes the difference between European authors and American ones.

¿Sabías que...?

- CuriosidadesTo perform the scene in which Kaspar learns to walk, actor Bruno S. knelt for three hours with a stick behind his knees until his legs were too numb to stand.

- PifiasIn a brief scene we see a stork eating a frog with its legs tagged (ringed), but bird ringing didn't start until the end of the nineteenth century, decades after the life of Kaspar Hauser.

- Citas

Opening caption: Do you not then hear this horrible scream all around you that people usually call silence.

- Créditos adicionalesOpening credits prologue: One Sunday in 1828 a ragged boy was found abandoned in the town of N. He could hardly walk and spoke but one sentence.

Later, he told of being locked in a dark cellar from birth. He had never seen another human being, a tree, a house before.

To this day no one knows where he came from - or who set him free.

Don't you hear that horrible screaming all around you? That screaming men call silence?

- ConexionesFeatured in Was ich bin, sind meine Filme (1978)

- Banda sonoraCanon in D major

Composed by Johann Pachelbel

Selecciones populares

Inicia sesión para calificar y añadir a tu lista para recibir recomendaciones personalizadas

- How long is The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser?Con tecnología de Alexa

Detalles

- Fecha de lanzamiento

- País de origen

- Idioma

- Títulos en diferentes países

- The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

- Localizaciones del rodaje

- Croagh Patrick, Westport, Mayo, Irlanda(archive footage)

- Empresas productoras

- Ver más compañías en los créditos en IMDbPro

Taquilla

- Recaudación en todo el mundo

- 3451 US$

- Duración1 hora 50 minutos

- Mezcla de sonido

- Relación de aspecto

- 1.66 : 1

Contribuir a esta página

Sugerir un cambio o añadir el contenido que falta

Principal laguna de datos

By what name was El enigma de Gaspar Hauser (1974) officially released in India in English?

Responde