It took the brutality and slick videography of ISIS to bring Libya back into the headlines, highlighting the lawlessness that reigns in that country.

ISIS’s outrageous atrocities on Libyan soil are a far cry from the optimism I observed in July 2012, when Libyans went to vote in the elections after the overthrow of Moammar Gadhafi, the man Ronald Reagan called “the mad dog of the Middle East.”

So what went wrong?

Reasons for euphoria after Gadhafi

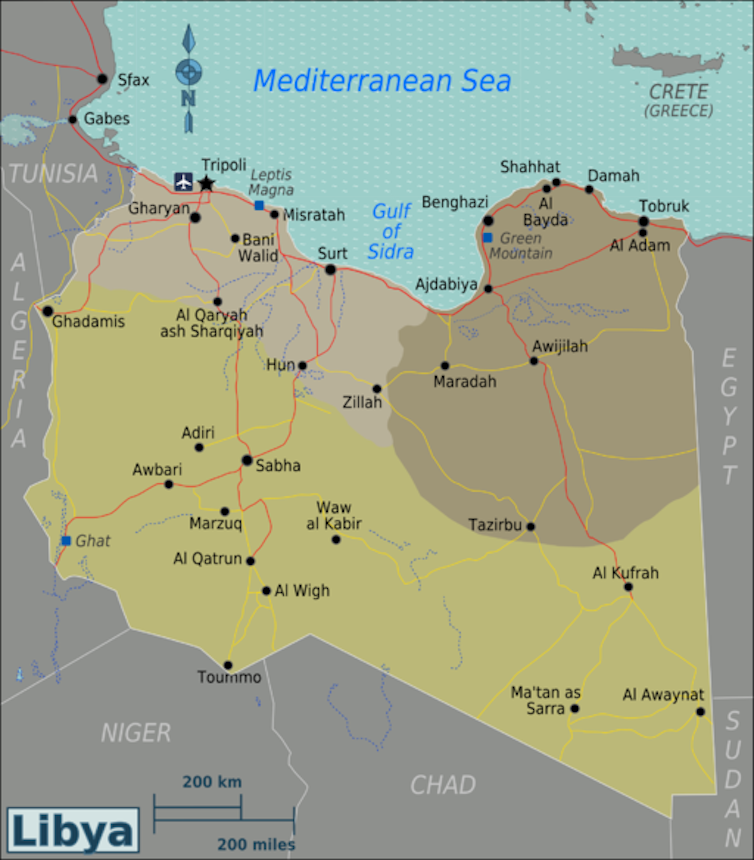

I was working as a US diplomat in Tripoli in 2012, and although the political scientist in me cautioned that elections alone do not a democracy make, I was nonetheless caught up in the euphoria of the moment.

One of my reasons for optimism was that the complete collapse of the Gadhafi regime meant that Libyans could build their new state and democracy from scratch, unencumbered by potential spoilers such as a powerful military (witness neighboring Egypt).

I also had a strong sense that the US and other Western countries were well positioned to support Libyans in their democratic aspirations. We had supported the anti-Gadhafi rebels in what was a genuinely indigenous uprising, but following their victory we had done the right thing and avoided the heavy-handed, military-centric, nation-building approach that had achieved limited success in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Libyans from all walks of life seemed genuinely grateful for the role we and other coalition partners had played in supporting the revolution. Indeed, a Gallup poll taken in August 2012 showed showed that Libyans held the most positive views of the US ever recorded in the Middle East and North Africa.

Unlike neighboring Egypt, where I had also lived and where cynical anti-Americanism was pervasive in the media and popular discourse, in Libya it seemed to be limited to a few hardline Islamist militias, which at the time were not central players.

Runes not read

In retrospect, both Libyans and their international supporters may have been so giddy with victory that they missed the looming threats.

Even in the heady months following Gadhafi’s demise, the debilitating consequences of state weakness and institutional collapse were evident.

Institutional weakness has a long history in Libya. It was inherent in Gadhafi’s governing ideology of statelessness, and even the monarchy that preceded him avoided building strong, capable, central institutions of governance. Regional and tribal identities were strong. Oil revenues were flowing. There did not seem to be a need for state building.

My Western diplomatic colleagues and I attempted to engage the new Libyan authorities in concrete proposals for cooperation. I worked closely, for example, with Libyan universities and Ministry of Higher Education. All the well-intentioned officials I met with professed an eagerness to sign agreements with their American counterparts but when push came to shove, nothing happened.

On the one hand, there was the long shadow of the cautiousness and institutional paralysis that had characterized Gadhafi’s long rule. On the other, Libyan institutions simply didn’t have the capacity to absorb outside assistance, much less implement plans and projects.

And then there was the problem of the militias and their weapons.

A shockingly large percentage of the world’s known MANPADS, shoulder-fired missiles capable of taking down aircraft at lower altitudes, were on the loose in Libya – an estimated 20,000 of them. The militias were eager to convert the soft power of their revolutionary triumph and the hard power of their weapons into access to resources and power.

The tension between these militias and the transitional authorities, many of whom had served in Gadhafi’s government or returned from exile abroad (including the US), were palpable.

The new leaders were people like Ali Tarhouni, a secular-minded and Westernized Libyan-American economics professor who served as finance minister and is now head of the commission charged with writing the country’s constitution. They had little in common with the so-called thuwwar or revolutionary fighters.

The militia leaders may not have been given the top government posts, but they were charged with filling the security vacuum – and handsomely compensated for doing so. But plans to integrate them into legitimate state-controlled security forces, so central to peace-building and stability, were put on hold.

Islamist build up

Some of these militias, perhaps more than we recognized at the time, had ideological orientations and agendas that were hard to reconcile with the democratic aspirations and pro-Western feelings I have described above.

Islamist militias of various stripes have been a part of the volatile post-Gadhafi mix from the beginning. The men who joined them had roots in the violent anti-Gadhafi opposition known as the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG). Many had fought as jihadists on numerous battlegrounds: Afghanistan, Bosnia, Iraq.

They may have been only a small number among the combatants 2011 but they were among the fiercest frontline fighters and had the biggest ax to grind with Gadhafi and his regime.

In the summer of 2012, a group of them bearing the black flag of violent jihad held a rally in the center of Benghazi, the cradle of the Libyan revolution – they were quickly chased away by Benghazinos.

In the months that followed they asserted themselves by bulldozing holy graves attached to mosques (they consider the worshipping of graves a form of apostasy)and by launching a campaign of attacks and assassinations against Westerners and those they deemed to be pro-Gadhafi sympathizers.

Over time, the vast unguarded borders and lawlessness of post-Gadhafi Libya provided the ideal environment for jihadists of various stripes to set up bases. For ISIS, Libya provides an opportunity not only to extend the caliphate, but to do so far away from coalition airstrikes in Syria and Iraq.

Could it have been different?

As I watch Libya drift further away from the promises of the 2011 revolution and as I hear an increasing number of Libyan friends and contacts tell me that perhaps things weren’t so bad under Gadhafi after all, I struggle as both a scholar and former practitioner with the question of what the West could, and should, have done.

If we had remained more diplomatically engaged after the attacks on the US mission in Benghazi, would it have made any difference? Did we “over-learn” the lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan, and swing the pendulum too far toward disengagement?

I think about my own projects supporting Libyan civil society organizations that were working in the rule of law and media areas. Such organizations had been virtually non-existent under Gadhafi. Was this a mistaken effort? Civil society, after all, needs a functioning state and security to thrive.

And then I think about other places I have worked in and studied, such as Kosovo. There the role of NATO and UN missions in securing key infrastructure (such as the airport) and reconstructing the judiciary were vital in stabilizing the territory after the war in 1999.

Could the US and its partners have seized upon the deep reservoir of goodwill in Libya that followed the intervention of 2011? Working with Libyan government institutions was difficult. But perhaps a more robust approach might have helped build the security and institution-building that was so desperately needed to forestall the situation that Libya finds itself in today.