This essay is the third in a series of reports from The Nor, an investigation into paranoia, electromagnetism, and infrastructure, undertaken as part of MIRRORCITY, an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London.

On Wednesday 17th and Monday 29th of December 2014 I made two expeditions by bicycle, the first of forty miles from Slough to the City of London, the second of forty-five, from the City out to Basildon in Essex. The locations and associated documents appear on the map of the Nor, while documentary photographs from the expeditions are available on Flickr.

In July of 2012 I found myself on London Bridge, some time after sunset, among some thousands of other Londoners, awaiting the opening of the Shard, London’s – and briefly Europe’s – tallest building. Citizens had been promised a spectacular son et lumière show, complete with lasers illuminating the landmarks of London, and been urged to watch the spectacle via video feed on Facebook. Despite that, huge crowds had turned out in person to watch – and they were destined to be disappointed.

At the appointed hour, the crowd was tense with expectation. And, spectacularly, nothing happened. The great glass monolith briefly changed colour. A couple of weedy green beams, as if from handheld torches, danced on its facade. As a comment on the Shard’s Facebook page stated, before being hastily scrubbed: “poo”. It was at about this time that I unveiled a large placard bearing the words “ALL HAIL SAURON”, but that is another story.

What did happen, however, after the crowds had gone home, was that an entirely different story was told in public. The next day, the newspapers and news sites were filled with stories of the “dazzling” show, and even pictures of sharp beams of light cutting through the night sky. They reported an event which did not happen; they showed pictures of a thing which nobody had seen.

Some months later, I first watched the artist Omer Fast’s film 5,000 Feet is the Best. In it, an actor recounts the testimony of a military drone pilot, a man who has watched militants and civilians from the air for days at a time, and, sometimes without knowing which is which, opened fire on them. During his monologue, he recounts the laser targeting of a suspected IED site:

“We call it in, and we’re given all the clearances that are necessary, all the approvals and everything else, and then we do something called the Light of God – the Marines like to call it the Light of God. It’s a laser targeting marker. We just send out a beam of laser and when the troops put on their night vision goggles they’ll just see this light that looks like it’s coming from heaven. Right on the spot, coming out of nowhere, from the sky. It’s quite beautiful.”

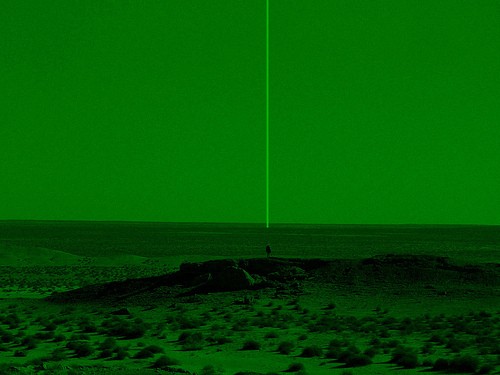

I couldn’t find any pictures of the Light of God, so I looked up images of laser targeting and night vision systems on the internet, and, in Photoshop, made this one:

Immediately after making it, I realised what I was looking at, what I had missed in the baffling recreation of the Shard’s non-event. The laser beams put out in honour of the Prime Minister of Qatar and the Duke of York were not meant for human eyes, but instead were perfectly calibrated for the long exposures of high-end cameras, the devices owned by newspaper snappers and professional photographers. It was a hack, but a professional one: power speaking directly to power through the electromagnetic spectrum.

Likewise, those Marines in the desert witnessing the Light of God were accessing a privileged segment of the spectrum through the deployment of expensive night vision goggles. The standard military issue AN/PVS family of night vision optics use a gallium arsenide photocathode to extend photon sensitivity into the near-infrared, where the illumination of the night sky, and more laser wavelengths, can be seen, and cost some three to four thousand dollars a piece.

The scientific precursor to the Laser was the Maser, a device which produced oscillations not in the visible light (L-aser) frequencies, but in the microwave (M-aser) range: the Super and Extremely High Frequency bands beyond the infrared. Today, microwaves are used extensively for point-to-point telecommunications – that is, communications which require a high-bandwidth, high-speed link between two points, rather than a wide broadcast – because their small wavelength allows them to be focussed into narrow beams. If you look up to the roofs of tall buildings, it’s not hard to spot small, deep dishes nestled among the tall rectangular antennae increasingly scaffolded upon them. The tall bars are most likely mobile phone receptors; the dishes are microwave relays, backhauling their take to the network’s centre.

In the epilogue to his 2014 book Flash Boys, American writer Michael Lewis goes for a bike ride too. He’s accompanied by four members of the Women’s Adventure Club on an expedition to the Appalachian mountains in Pennsylvania, where the tour group encounters a tall tower, festooned with microwave dishes, on a rugged and remote peak. Lewis is enigmatic about its purpose, stating only that “a day’s journey in cyberspace would lead anyone who wished to know it into another incredible but true Wall Street story, of hypocrisy and secrecy and the endless quest by human beings to gain a certain edge in an uncertain world.” (For those dying to know, the internet has the follow-up.)

Flash Boys tells the story of the rise of High-Frequency Trading, a form of algorithmic trading on stock exchanges which relies primarily on arbitrage: making the most of small differences in the price of financial instruments. The speed of contemporary computation means that HFT traders need hold their positions for only fractions of a second in order to make a tiny profit – but they can hold millions of these positions every day. Furthermore, the speed of communication between exchanges and traders becomes a huge factor in the market. The trader who is “first to market” with any news, or knows about an event on another exchange before anybody else, is at a huge advantage. Speed can literally be turned into money, and so speed itself becomes desirable, and highly valuable.

There is nothing theoretically new in this. Paul Reuter used carrier pigeons to move financial information between Berlin and Paris faster than the post train and the still evolving telegraph network, exploiting this information arbitrage to build the foundation of his news agency. Later, he persuaded incoming ships captains passing the south-western tip of Ireland to throw canisters containing news from America into the sea, so it could be telegraphed to London from the station at Cork, arriving before the ships themselves.

The explosion in High-Frequency Trading in the last decade has been driven by infrastructure. First came high-bandwidth fibre optic cables, which shoot light through hair-thin cables, and then came shorter fibre optic cables: the speeds at which HFT operates means that advantages of less than a millisecond can translate into vast profits. Hence the fame of Spread Networks, which between 2009 and 2011 spent millions of dollars digging a more direct tunnel between Chicago, home of the Mercantile Exchange, and Carteret, New Jersey, home of the NASDAQ. Spread’s shorter route shortened the round trip time between the two exchanges from 14.5 milliseconds to 12.98: one and a half thousandths of a second. But the HFT firms quickly realised that even shorter times were possible. Light in glass travels much slower than light in air; data in fibre optic cables travels about 50% slower than microwaves beamed through the atmosphere. Hence Lewis’ discovery on the Pennsylvanian mountain top.

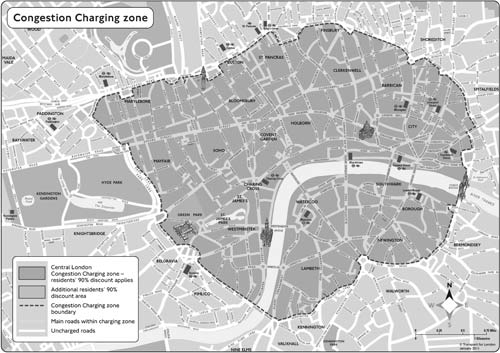

Another consequence of HFT is that trading no longer happens between people but between machines, and geography is virtually irrelevant. So while we still think of the capital-C City of London as the financial heart of the metropolis, the real action happens on the fringes, out beyond the orbital motorway in the adjoining counties, in Berkshire and Essex. It happens inside machines, inside great halls of machines, behind high fences and windowless walls, connected by invisible – but increasingly direct – microwave pathways. The holy grail is Low Latency: the least possible elapsed time between locations, between trades, between coins.

In the town of Slough twenty-five miles to the west of London, the sprawling Slough Trading Estate is home to the Equinix LD4 datacentre, the London Stock Exchange’s extramural home. In 2013, the LSX announced that, in partnership with NexxCom Wireless, it had constructed a microwave path directly from LD4 to the rooftop of its London datacentre on the edge of the City, just behind Liverpool Street Station. This service, it boasted, would “operate over an optimised path that deviates only 3% from a straight line between the two locations. This will enable clients to transmit 30% – 50% faster than traditional fibre connections.”

The area around LD4 feels like its being terraformed. On every street in every direction old factories and machine shops are being torn down, the ground levelled, and in their place are rising vast datacentres, information fortresses, physical instantiations of the internet and digital communications. A google search does not do it justice: as so often, you have to seek the ground truth. That truth is that a new industry is being built upon the old, more private and more obscure than its predecessors, but furiously gleaming, powered by data rather than people. If you think that London’s skyscraper boom is impressive – the Shard, the Walkie-Talkie, the Cheesegrater, the Gherkin – go to Slough. It is not height that matters, but bandwidth.

At one corner of LD4 a tower rises up, barnacled with microwave dishes. Through planning applications and radio licenses it’s possible to trace the routes these signals travel: each license lists the start and end location of each point-to-point link. Follow these lines; follow the money.

Westwards, the lines head for the transatlantic cable points at Porthcurno and Brean; eastwards, the first point is close: a thicket of dishes atop the old Slough parcel sorting office. Nearly deserted, a grimy notice is taped to the gatepost. It’s a planning application: “CHANGE OF USE OF BUILDING FROM POSTAL SORTING OFFICE (SUI GENERIS) TO DATA CENTRE (CLASS B1)”. Nearby, traffic roars around HTC Roundabout, planted with topiary in the form of the mobile phone manufacturer’s logo.

I am following the lines attributable to Optiver, a Dutch proprietary trading firm reputed to have some of the best – i.e. shortest and thus fastest – links in the business. Optiver is a classic High Frequency “market maker”, arbitraging different markets to provide bid and ask positions to buyers and sellers, but holding no positions of their own for more than minutes at a time: a man-in-the-middle operation made possible by being milliseconds ahead of the competition. Hence the Slough post office, hence the lonely outcrop of Evreham Adult Education Centre on Iver Heath. the bare metal of the Hillingdon Fire Station transmission tower, the watertower in Perivale.

Each of these sites appears on a license or planning application filed by Optiver in the last few months. Some of them have microwave dishes mounted, some of them do not – it’s not uncommon for low latency providers to apply for a range of sites and licenses, and then fill in the most direct route they’ve managed to put together.

The road out of Slough to Iver gets urban-rural fast: muddy tracks, scrap metal yards, horses grazing on scrub beneath pylons. My bike bogs down but the sound of heavy traffic is not far away. I pass through The Orchards, a neat and compact “park home” of pre-fab bungalows for the retired – it’s quiet, but then it’s cold. The microwaves are silent overhead. Atop the hill at Evreham, the highest thing for miles around is the Adult Education Centre, whose three stories are topped with an array of aerials. According to a report to the Buckinghamshire County Council’s Education, Skills and Children’s Services Select Committee in November 2014, the county’s Adult Learning programme has an annual budget of £5.6m, serving a population of half a million people at some twenty centres from local libraries to sports centres. Optiver, who have been granted a license to site a microwave link on top of the Evreham Centre, published profits of £136 million in 2013. Their total trading income was £365 million, while employing just 600 people.

On the next hill over from Iver is Hillingdon Fire Station, whose radio mast is another licensed Optiver site. Hillingdon is not one of the ten London fire stations scheduled for closure under the Fifth London Safety Plan, although it will have to take up the slack from the loss of those stations, as well as that of 14 further engines and some 552 firefighters, a proposed saving of just £29m, while the firefighters themselves are having their pensions slashed.

On the road between these two sites I pass Hillingdon Hospital, a towering slab erected in the 1960s on the site of the original eighteenth century Hillingdon workhouse. At its opening it was hailed as the most innovative hospital in the country, and as of 2008 it is the home of the experimental Bevan Ward, a cluster of special rooms researching patient comfort and infection rates. Despite this, the hospital today comes in for frequent criticism, like many others of its political and architectural era, for crumbling facilities, poor hygiene, high hospital infection rates, bed shortages and cancelled operations. The most recent report from the Care Quality Commission voiced concerns about staff shortages, and the safety of patients and healthcare workers due to lack of maintenance on the ageing premises.

In 1952, Aneurin Bevan, founder of the NHS and namesake of the experimental ward, published In Place of Fear, in which he justified the establishment of a National Health Service: “The National Health service and the Welfare State have come to be used as interchangeable terms, and in the mouths of some people as terms of reproach. Why this is so it is not difficult to understand, if you view everything from the angle of a strictly individualistic competitive society. A free health service is pure Socialism and as such it is opposed to the hedonism of capitalist society.”

Atop Hillingdon hospital are two large microwave dishes. The current site licenses are for emergency services network Airwave, and the mobile phone networks EE (Annual turnover 2013: £6,482m) and Vodafone (2013/14 revenue: £43.6bn). Both of those companies trade on the London and New York stock exchanges, and given its position, it’s no surprise that Hillingdon Council’s website reveals an application from Decyben SAS to place four more half-metre dishes on the hospital’s roof. Decyben is a shell company for McKay Brothers, the largest and fastest High Frequency Trading network provider in the US, and now a keen competitor in Europe. When McKay opened their dedicated New York – Chicago microwave path in 2012, their partner Aviat Networks stated that “a single millisecond advantage could equate to an additional $100 million a year to a large high-frequency trading firm.” McKay’s link gained them four.

Bevan also wrote in 1952: “We could manage to survive without money changers and stockbrokers. We should find it harder to do without miners, steel workers and those who cultivate the land.” Today, those changers and brokers perch atop the very infrastructure Bevan laboured to construct.

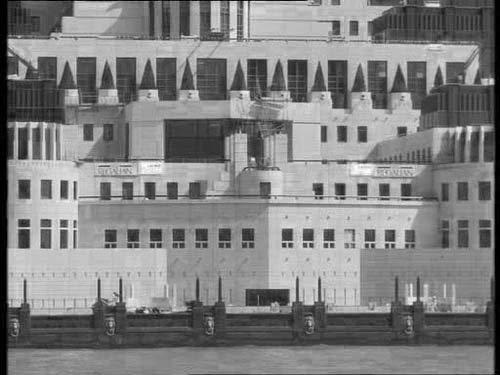

On the other side of London, the microwaves emanate from the unmarked London Stock Exchange datacentre on Earl Street. On a bright, cold winter’s morning between Christmas and New Year almost everything is closed, but the datacentre hums away, cooling vapour crystallising in billowing white clouds overhead, the condensation of money itself. At weekends in the City you can dowse for datacentres by the air conditioning alone, the loudest thing for streets around.

From here out east towards the Thames estuary the links are similar too: microwave dishes perch atop a council tower block next to West Ham stadium, an office block in Basildon, a Gold’s gym in Dagenham, railway depots and vacant industrial estates in Upminster and Laindon. The territory these links pass over is depressed as well: the East London borough of Newham is the city’s most populous, most diverse, and poorest, by any measure, and has been particularly targeted by the coalition government’s austerity cuts, expecting to lose up to 25% of its budget between now and 2016 (in the least deprived areas of the country, the average cut is just 2.5% over the same period).

This line ends at another unmarked facility: the New York Stock Exchange’s datacentre in Basildon, Essex. Inside this vast windowless hall is seven acres of computing space, including the matching engine for the NYSE Euronext exchange, and the machines belonging to the companies which trade on it. Its location halfway to the east coast of England puts it closer to the microwave links which reach across the Thames estuary to Sheerness and Dover, across the channel to Dunkirk and Nieuwpoort, and ultimately across Belgium to the Deutsche Börse exchange in Frankfurt, the most important European trading hub. The NYSE is the world’s largest stock exchange with a £16.5 trillion market cap in December 2014. In 2013, £110 billion was traded on average every single day.

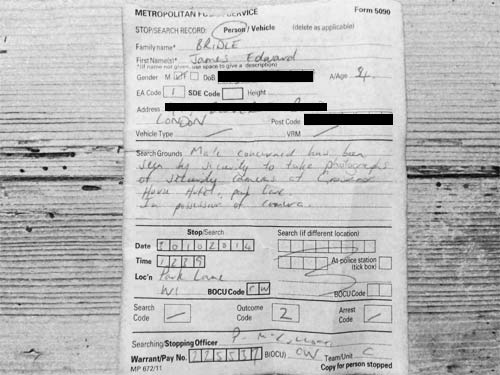

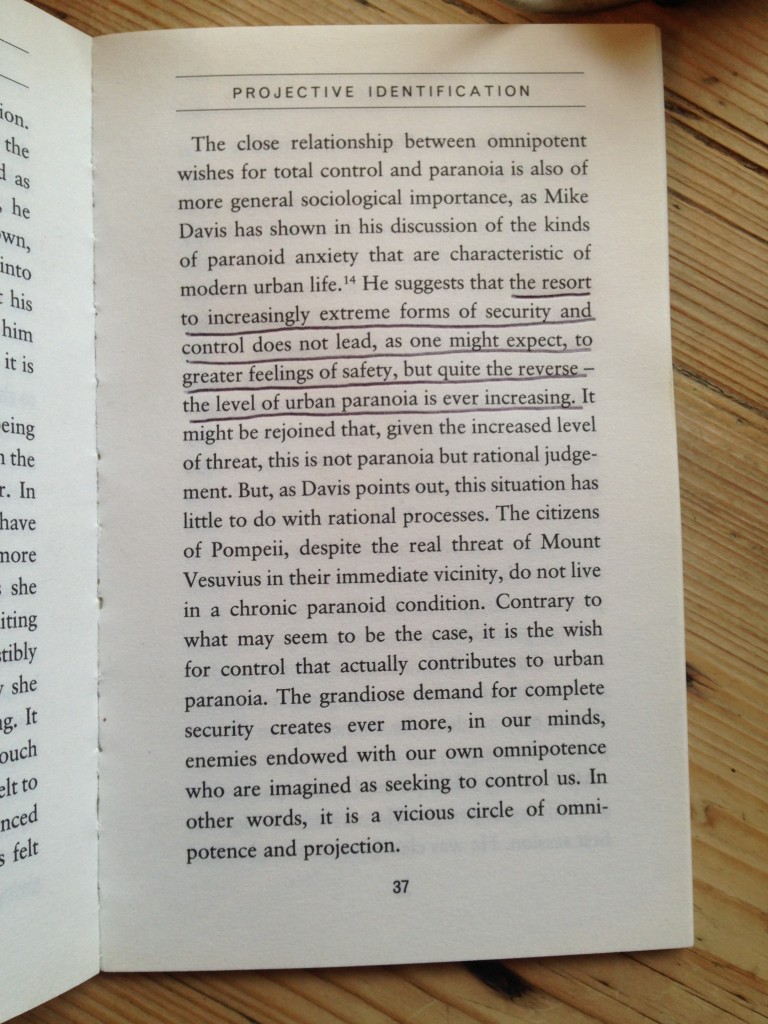

Numbers, numbers, numbers. It’s grim out here. The road is cracked, the hedgerows are filled with rubbish thrown from car windows, I am accosted again by private security guards who don’t want me looking at their building, who threaten to call the police when I object to their request to run background checks on me. But the sun is shining; it is a beautiful winter’s afternoon. If you want a mirror city, this is it right here: billions upon billions of pounds being beamed across the rooftops of council blocks and crumbling hospitals, the haunts of pirate radio DJs now the domain of private hedge funds, and the once buzzing city centre finance sector displaced to silent halls on ring roads, staffed only by angry men in high-vis tabards.

In the late 1980s, on the corner of a dull, industrial British Nuclear Fuels complex in Capenhurst in Cheshire, there rose up a narrow, cylindrical, thirteen-storey tower. To the casual observer it appeared to be part of the BNFL works, which produced and still produces enriched uranium for Britain’s nuclear power stations. But in fact the tower was built by the Ministry of Defence, on a specially purchased patch of land, which sat on an especially particular line of sight, between Gwaenysgor in North Wales and Pale Heights in Cheshire.

Gwaenysgor and Pale Heights are the locations of two British Telecom microwave towers, and between them flow, some forty metres above the ground, all telephone communications between Ireland and the British mainland. Situated well within the slowly spreading beams from these towers, the Capenhurst tower was operated by GCHQ, and used to intercept and monitor all communications between the Republic, Britain and Europe. It did this by simply poking its top storeys into the beam, and recording everything that flowed through the atmosphere around it, in much the same way that GCHQ’s Tempora system intercepts fibre optic communications at Bude in Cornwall and elsewhere today. (The Capenhurst tower, built at a cost of some £20m, was sold and eventually demolished just ten years later when Irish telecommunications were switched to a different system.)

What would it take, I wonder, to dip into the traders stream of money, to divert a little of the fatty order flow towards the people it passes over, towards the hospitals and homes, towards the small-c city itself? Could one fly kites, loaded with receiving equipment, from fields on the edge of London, from the horse paddocks of the Dagenham Chase or the marshes of the Colne Valley, nosing into the beamfield, nudging the numbers a little left or right, or downwards towards the folk who actually live, oblivious, at ground level? Above estates and wards, retirement parks and schools across the city, great mylar-coated barrage balloons bob in the winter breeze, their silver surfaces reflecting just a little of the vast wealth passing unseen through the thick atmosphere.

Bevan, again: “Discontent arises from a knowledge of the possible, as contrasted with the actual.” Inequality is engineered, and deliberate. It is an arbitraging of social conditions, a perpetuation of the existing situation by those who seek to profit from its differences.

As we have seen throughout our exploration of the Nor, whether in the hidden cameramen of the metropolis, the field scaffolds of the airways, or the canopied eyries of the oligarchs, technology is used to obscure and efface systems of control and profit, but it also reveals itself, startlingly clearly, if one knows where to look. I have attuned myself to hidden oculi, to radar, to rooftop aerials, and to the motion of waves in the electromagnetic spectra; each just an outgrowth, a prosthesis, of deeper legal, political and social systems. On the train home from Essex, muddy, cold, and weary, the last of the December sun sparks across a field of solar panels and the countryside catches fire.

* For this episode of the Nor, I am particularly indebted to the work of Alexandre Laumonier, a Belgian anthropologist and academic studying HFT, who has catalogued at length the infrastructure, physical and legal, of High Frequency Trading on his blog, Sniper in Marwah. For much more fascinating background on the engineering and politics of this world, see the series of posts entitled “HFT in my backyard”.

** I also built my own tool for querying Ofcom’s licensing data. It doesn’t work everywhere or very well, but it can be found here: NOR Spectrum Analyser.